Interview: Arthur Jones and the Untold Story of Titanic

What happened to the six Chinese survivors of the RMS Titanic? As we approach the shipwreck’s 110 year anniversary, British filmmaker Arthur Jones tries to discover the stories of the six passengers who disappeared after the 1912 tragedy.

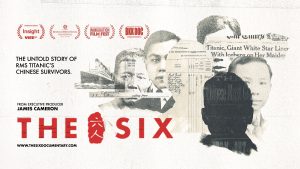

“The Six” is a documentary about the Chinese passengers on the Titanic. For a century, these survivors were framed as stowaways, cowards, and losers because of the xenophobia and racism from western societies. The film presents the terrible incident with an ethical lens by looking at the global immigration history and legislation through these six survivors.

From the biggest obstacle to some personal significance, Jones spoke to The Independent’s Xinyan Fu about the backstory of creating this historical documentary and his experience as a filmmaker in China.

Xinyan Fu: In the director’s statement you put on the movie’s website, you mentioned that the leading researcher Steven Schwankert came to you about six years ago. Can you tell me a little bit more about your inspiration for creating this film?

Arthur Jones: Well, it’s a slightly complicated issue for me because Steven and I, and our producer, had finished another film that was also about maritime history, and something around 2013. I felt like it was an interesting genre, like it was a documentary and had a historical theme. It was almost like the film was asking the question, and I really responded to that. And I remember at some point, Steven said to me that we should do a story about the Chinese guys on Titanic.

I obviously know about Titanic. It’s very famous. So my first reaction was I don’t really want to do anything about Titanic. It feels a little mainstream. But then, what persuaded me was a few things. First, the reaction of everyone around us was like: Oh my God, that’s unbelievable, that’s like a crazy story, how do we not know about that? I was like, oh, maybe this is a really easy pitch. Everyone goes for it. In documentaries, that’s a hard thing, so that felt inspiring. And then the second part of it was it just felt like we had the right team, in the right place, at the right time. It would be such a pity to miss this story. Nobody else had done it. It’s so unusual to find a new story on Titanic. And it just kind of came together in that way. So it was bit by bit, it wasn’t like I was immediately thinking I’ll make this film. I was just gradually kind of persuaded until eventually, it just had a kind of natural momentum to it.

XF: You mentioned that your last scene is with James Cameron (Director of “Titanic”). I actually think it’s nice that you included him in his film. How did he get involved? What was his initial reaction when you got in touch with him about this project about you and the Chinese men on the Titanic?

AJ : My main reason for contacting him is because of the deleted scene that he shot for Titanic showing a Chinese man floating on some wood. Cameron obviously knew something about the Chinese story because he shot this scene that we knew was a real scene. But it was weird that Cameron knew about it because, you know, it took us a while to find that story. And I wanted to ask him: Why did you shoot it? How do you know about it? And then I guess I also wanted to ask him: Why did you end up deleting it? Like, what was the issue with that? And then the last thing I wanted to ask him was also because I had this feeling that maybe the scene of Fang Lang (Wing Sun Fong) on the wood had inspired the final scene of Jack and Rose on the wood because it was very similar. So I wanted to ask them all those questions.

Early on, we talked about maybe we should try and get in touch with Cameron. But it didn’t seem very likely. Obviously, he’s a very famous director and probably very busy, so we didn’t know if it was going to work out. Finally, right towards the end of the project, our other executive producer managed to get a contact detail, and I wrote an email explaining how we’d love to meet Mr. Cameron and ask him some questions. And then, the next day we had already received the reply, and it said, James already knows about your film. Actually, he’s been kind of following it for a while, so he had already heard about our project. And he was quite interested in the project.

XF: Did he really answer your question about why he cut the scene? Because also, I was really curious about that. When my friend and I were watching it, a theory that came out was that because these two scenes are so similar that if you put them both together, then the finale of Jack and Rose would not be as profound?

AJ: That’s right. Well, I did ask him that question. And, I don’t want to misquote him, but I think his answer was basically what you’re saying. He said we cut it for editorial reasons to do with pacing and things like that. So the film ended up inspiring that Jack and Rose story, but as you say, it would be a bit weird to the two mirrored scenes so close to each other. So you can see why that makes sense. And that’s what I had always guessed, that he wanted to recreate that scene. But then, once he had it, and he was editing, he realized that it was a kind of a repetition of the theme that it had inspired.

We actually found the actor who played Fang Lang (Wing Sun Fong) in that scene. We interviewed him. It’s a funny story, because that actor, in fact, is not an actor. He’s a Chinese American guy in the visual effects team. And then, during production, Cameron came to him and said: Hey, I’ve been thinking about putting this Chinese character into the film, would you mind doing it? And he happened to have long hair. So they tied it back, like a kind of 19th century Qing Dynasty Chinese, and made the clothes for him. And during filming, they added him into a few scenes in the background. And then, right towards the end, they filmed the scene of him on a piece of wood.

And there’s lots of things about that scene that I think are kind of cool. First of all, it’s actually pretty accurate that he’s rescued by the actual lifeboat that rescued Fang Lang. The actor is speaking Cantonese in the scene. Cameron and this actor guy, they didn’t know Fang Lang speaks Cantonese. But that’s the language that the actor speaks. He doesn’t speak any other Chinese languages. So he had him speaking Cantonese, which is just a guess, but it turned out to be right. The funny thing about this is that, when Cameron made that scene, he didn’t know that the character is called Fang Lang, but he got them pretty accurately. It’s pretty cool how well they did it.

XF: What were some biggest obstacles that you’re facing when making the film when you’re doing research?

AJ: The first big obstacle is a research thing. And that is just the incredible difficulty of doing Chinese migrant history. It’s just so much harder than any other national group that I know about. In fact, in the early days of this project, we began to contact Xungen people, the family tree people, genealogists, who are experts at finding family history and stuff. And we were actually turned down by several. It’s not that they didn’t want to do it, or they’re not interested. They just said it’s just too hard for Chinese families. It’s just the obvious thing, you know, look at the list of the passengers on Titanic. Look at their names. What’s the first thing you notice? They’re all two-character names. I mean, do we really think they’re all two-character people? I don’t think so. And in 1912, even now, most people are three characters. So on the list, there are only two characters. And then, if you look at all the passenger lists of Chinese people traveling to America in the early 20th century, I would say like 90% of them are two characters.

It’s just a real struggle: they don’t want to go around telling everyone that complicated three-character name that no white person in America can even say the name. At that time, they didn’t have the system where they called themselves like Johnny, or you know, Ben, John or something, they just took the Chinese name, and they deleted a character, and they became a two-character name. But it’s even more complicated than that, because you don’t know which character they deleted: Did they delete the family name? Was it the first character or the last character of the name? Or have they just made up a new name with two characters? And then you add to that: they’ve made up a new name because maybe if you’re working on a ship, and you’re a Chinese sailor, the captain may be American, and you just can’t be bothered to tell him your full name. It’s just too complicated. So you tell him your name is like Ah Lam. And Ah Lam isn’t even two characters. It’s only one character with an “Ah” on the front. So that’s the real problem. And then, even on the list for Titanic, we’re just a very specific example. I think three of the survivors, when they arrive in New York, four days later, their age changes. So these guys are constantly changing names, constantly changing ages. Sometimes they write that from China. Sometimes they read that from Canton, sometimes they would write that they are from Hong Kong.

At the beginning, it drove us crazy. And we were trying to find out what’s going on. We don’t really understand. Later, we just realized that these guys have no rights anywhere, and the only little piece of power that you have is your name and your age, and maybe where you come from. So anything that you can do to try and make your life easier. You will use that information to try to do it.

Doing this kind of historical investigation of that generation of Chinese migrants is a pretty big barrier to entry. A lot of people don’t want to do it because it’s just incredibly time-consuming. And even when you find someone you think it’s the right person, it’s not always the right person. It’s very, very complicated to work for sure. But you know, I don’t want to complain about that, because I think the fact that it’s so difficult is the explanation of why no one made this film before. And nobody did a book about it before because it’s just very, very difficult to do. So the fact that it’s difficult kind of protected the story for a long, long time.

XF: What are some of the personal significance to you to create this documentary?

AJ: The one thing I would say that I really have come to feel about, that really affected me about this film, and I got to preface this by saying I do not compare myself to the experience of Fang Lang and Chang Chip, and Lee Bing. I mean they’ve been through incredibly deep trauma and were awfully discriminated against for decades. So I’m not comparing myself to that. But I would say that sometimes when I was thinking about Fang Lang as an undocumented worker, part of the country but not really part of a country, wanting to settle in America, wanting to get married, wanting to be a rounded person with a rich experience. Just towards the end of the project, a few times Steven and I talked about that and said, it’s a funny kind of parallel to our lives, that Steven and I have lived like 25 years in a country where you can’t really naturalize that you’re not Chinese, and where there’s no open immigration policy. And I’m just observing, I’m not making a judgment about that. So there’s some sort of parallel in that way you sort of feel part of the country or in, but you’re also not part of that country. I mean, in America, Fang Lang was what we now horribly called illegal, you know, he was an illegal immigrant, but I prefer to think of him as like an undocumented worker. But the flip side of that is that I’m a white British person living in China, and because of that status, I get lumped together and called an ex-pat, which I think is one of the most awful words in the English language. So why is he a worker or a migrant, and I’m an ex-pat? Do you know what I mean? So that sense of who you are and how you fit into a place is a very personal thing, and we all find our own place to be in the countries we settle in. And I think those issues have become more and more something that my mind thinks about a lot. And it’s led me, I think, to like, maybe a better appreciation of Fang lang and his life and his struggles.

XF: I know you also visit Tai Shan, and that’s like, one of the biggest communities for overseas Chinese because of its special geographic location and the politics. How do you think your film can help people at least get an idea of what the immigrant history is like for the Chinese community?

AJ: Well, I think my principal in this film was just to open up like boxes that haven’t been opened up. And for non-Chinese migrant families, families with different backgrounds in the U.S. or the U.K., I hope that they look at this and go: oh my god, there’s like these whole stories that we never knew that are part of the story of our country, how they came together and how they got formed. People would think that Titanic is like a story about rich and poor white people on a ship. It turns out there were black people on board, or Chinese people on board, or the Middle East and people on board. So that’s one thing, but I got to say even the other way around, the funny thing is we talk about Tai Shan: If you want to go to a place that knows about Tai Shan, it’s America. But within China, I would say the vast majority of people have never heard of Tai Shan. They don’t know the history of it. When we played this film in China, people often came up to me; They’re like: how did you know about Tai Shan? I’ve never even heard about that place. And I think that’s the same thing I want. I want people to watch it and be like, I had no idea, you know, there’s like this whole area that I didn’t know.

XF: I know the film was released in the U.K., and it was also screened at a couple of different international film festivals. What’s the next plan? Are you guys planning to put the film on streaming services or putting it on theater release in the U.S.?

AJ: Well, from halfway through the project, we were really lucky that we were approached by the theatrical distributors. So that’s an unusual situation for a documentary. It was great that we got to play in the cinema in China. That was a huge thing. We played on like tens of thousands of screens and stuff, that was huge. We’ve had some really great film festivals. We got the best documentary prize at Beijing. And we played at Vancouver, and we won the Audience Award there. It was just really thrilling to have people appreciate the film all over the place. And like you say, we played in Shanghai, we played in Philadelphia, we played at the immigration festival in D.C. There’s a few festivals still to go, but we’re sort of coming to the end of the festival run now. And last night was a U.K. theatrical premiere. So we’ve got a theatrical run in the U.K., which is amazing. We got a limited theatrical run there, I hope that gets extended. I would love to do a theatrical run in the U.S. My dream would be to start out small, maybe we could take the film to do screenings, maybe centered around Chinatown and stuff. I mean, we’ve had such great support from Chinatown communities and family associations based in Chinatown. So I’d love to do that. It’s something that we’re talking about. For broadcast rights, we have an agent and they’re selling the film to TV stations. And they’ve already started doing that. The film has already been sold to Australia, Japan, and Spain, and Hong Kong. And I think there’s more that are being negotiated. So it’s like with a film like this, you kind of have to do it piece by piece. I mean, I’d love to really make that work in Canada and the U.S. and the U.K. because they’re the other parts of the world where we actually feature stories there. We want to get on streaming platforms and on TV and theatrical wherever we can do that. But a film like this, you know, it’s like piece by piece. It just takes a long time to roll the film out.

Regions: United Kingdom, United States