Documenting a Man who Refused Interpretation

Salinger

(Shane Salerno. 2013. USA. 120 min.)

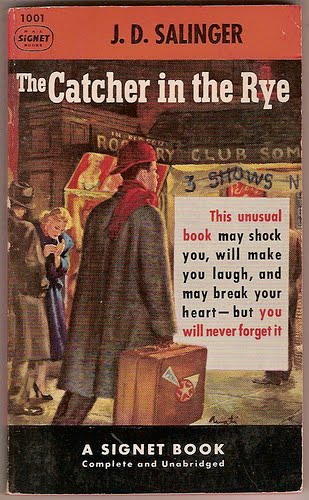

“Salinger and I got alone together, and I said, ‘Look, what do you want, you want some sales? These guys are supposed to know how to sell books, so screw it, let’s do it.’ So we did it.”–James Avati, who painted the original 25-cent paperback cover (right) of The Catcher in the Rye.

The author, J.D. Salinger, didn’t want Holden Caulfield or his sister, who aren’t described in his first novel, illustrated at all. But he was amenable to a painting of Holden sitting in the rain on a park bench, faced away, perhaps looking toward the New York Central Park carousel. Avati, who’d become Signet’s most frequent in-house illustrator, thought a better idea was to show Holden walking down Broadway with his Gladstone luggage and his hunting cap on backward, “expressing his pained reaction to people who like movies.” Avati prevailed, though like Salinger he was pained when the cover first appeared in 1953 with Signet’s added blurb “this unusual book may shock you, will make you laugh, and may even break your heart—but you will never forget it.” Signet’s paperback with Avati’s artwork enjoyed 27 reprints over the next 10 years, until Salinger changed publishers and mandated plain covers with no illustrations. Avati died in 2005, five years before Salinger. Avati’s painting—with a blue screen covering the blurb area, which the artist had smeared with white paint—sold at auction in 2010 for $21,500.

The incident above isn’t mentioned in Shane Salerno’s edgy and relentless new documentary, Salinger, but it might as well be counted as yet another nail that sealed America’s best-known unknown author into a small town life of retreat and near-isolation. Like two other releases by The Weinstein Company—The Artist and Populaire both critic’s choices—Salinger infuses large dollops of emotional urgency into subjects (a silent-screen movie star, a 50s French typing champion, a dead author) that in lesser hands could have stayed moribund. This isn’t to imply Harvey Weinstein has worked his same old magic into yet another corner of sleepy pop culture. But it may be more than simple coincidence that Salinger has the same snappy editing and pushy music score that gave The Artist and Populaire much of their pleasurable zest, and a tip-of-the-Hatlo-hat to Weinstein if he helped power-up these artifices.

Salinger is styled as a multi-platform documentary crash course in Salinger, tied into a new 698-page oral history by Salerno and David Shields, embellished with occasional reenactments (mostly on a bare stage with projections) that feel like Salerno and his varied team of producers may be test-driving a possible stage version of their book and movie. It’s a zero-to-60 biopic starting with Jerome David Salinger’s privileged upbringing on Manhattan’s Park Avenue and his first writing classes at Columbia University under Story magazine editor Whit Burnett, who’d become a mentor. Right from the get-go, “Jerry” Salinger teases his classmates that “J.D.” stands for “juvenile delinquent” and that his life goal is being published not in the mass-market Story (“I don’t want to write like O. Henry”) but in the upper crust New Yorker.

For a long time it doesn’t happen. The New Yorker rejects seven stories in a row, including A Slight Rebellion Off Madison which introduces the teen Holden Caulfield. Salinger trusts Cosmopolitan to publish another story without changes, but they shorten the title Scratchy Needle On A Phonograph Record to Blue Melody. Needing money, he sells his story Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut to RKO, which mashes his sensitive plot into the sudsy My Foolish Heart with Susan Hayward and Dana Andrews. His mentor Burnett promises to anthologize his best stories but that deal falls through. The struggling author falls head-over-heels in love with the stunning 18-year-old Oona O’Neill, starlet daughter of the famed playwright, only to watch her marry screen legend Charlie Chaplin.

Surrounding this series of setbacks are nearly a year of Staff Sergeant Salinger’s days and nights of war combat experiences, ranging from his horrific landing at Utah Beach on D-Day through the Battle of the Bulge and the slaughter at Mourtain, into his post-war interrogation of prisoners in a Nazi concentration camp. Director Salerno gives major screen time to these intense sequences, noting Salinger is shaping the initial chapters of Catcher under intense pressure, fear, and terror. When Salinger suddenly marries a 26-year-old ophthalmologist and possible Nazi war criminal, Sylvia Welter, in 1945 (a marriage he quickly annuls), we’re thinking he may be losing it. His one positive war experience seems to be meeting Ernest Hemingway in Paris, who encourages his writing.

But his singular triumph occurs in post-War 1951, with the publication of Catcher and the Signet paperback reprints of that and Nine Stories. The novel will sell 65 million copies (and still sells a quarter of a million copies annually). The film demonstrates how sudden fame can add vulnerability to an author already traumatized by combat and career defeats. The New Yorker’s editor William Shawn becomes Salinger’s new patron and publisher. A blitz of Hollywood bold-face names, from Billy Wilder to Jerry Lewis, approach Salinger with film offers. He replaces a very young Florida lover, Jean Miller, with a Radcliffe student, Claire Douglas, whom he marries in 1955. By then he’s exited Manhattan for a dark, almost featureless house on 90 acres in the woods of Çornish, New Hampshire. She gives him two children while he walls himself off from all humanity in a concrete cabin in which he spends most days writing. But writing what?

At several points Salinger the movie positions the author as a kind of late 20th century Howard Hughes. There were differences: Hughes was a 40s movie mogul who ran a studio by remote control and seduced (or failed to seduce) a string of A-list actresses; Salinger controlled his own fictional universe of feisty boys and longing girls, and he often reached out to replicate the girls in real life. He seemed to be searching for his next Oona O’Neill, and maybe he found her in his third and final wife, Coleen O’Neill (no relation and a nurse 40 years his junior) whom he married in 1988 and is seen only briefly at the wheel of their car. As a recluse he had little patience with the stream of visitors who tracked down his rural residence and waited with notebooks and long-lens cameras, but he promptly answered letters from adoring young women, who perhaps saw themselves in his stories.

Much of the heavy lifting in Salerno’s doc is done by a long-suffering Claire Douglas, and by Joyce Maynard, a Yale writing student who found herself on the cover of The New York Times Sunday Magazine in 1972. Douglas did 30 years with Salinger, and she and her daughter Margaret (seen in brief clips) reveal a strangely absent husband and father who dabbled in a host of religions (from Scientology to Vedanta Hinduism) and became more remote and removed as he aged. Maynard, who wrote one of the many Salinger biographies discussed in the film, spent less than a year with him but is more colorful in her memories. She tells us he liked Lawrence Welk and ran 16mm prints of dozens of classic Hollywood movies, of which Lost Horizon was a favorite.

You can’t tell whether Maynard saw Salinger as a lover, father figure, or a bag of money, but she did auction off 14 of his love letters for $156,000 and wrote a novel that became the Nicole Kidman movie, To Die For (in which Maynard plays Kidman’s lawyer, no less). Maynard is the one tough cookie in the film, distinctive amid the expected talking head authors (Tom Wolfe, Gore Vidal, E.L. Doctorow), actors (Martin Sheen, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Edward Norton), and even assassins (Mark Chapman, John Hinckley) who affirm the Salinger and Catcher legacies in conventional ways.

“Uncover The Mystery, But Don’t Spoil The Secrets,” warns The Weinstein Company marketing ads, over a drawing of Salinger shushing us. This refers, if you haven’t already guessed, to the question that haunts most of the two hours of Salerno’s documentary: what was Salinger writing between 1965 and his passing in 2010? Salinger’s wish was that the world would have to wait until five to ten years after his death to read the remainder of his life’s work. Salerno offers Twitter-length descriptions—already public knowledge—of what may be coming. And what’s coming? Think about the kid in the baseball cap worn backwards in James Avati’s 1953 illustration (above right). As they say, the past is prelude to the present… and the future.