The New York Film Festival Sept. 27–Oct.13

‘Read the Book, See the Movie’ defines a festival rich with literary excellence

This critic’s 62nd NYFF grew larger in size and younger in age this year. 73 feature films from 24 countries, with 18 of 32 pictures on the Main Slate by first-time directors. The fest continued to widen its outreach from its home base in Lincoln Center, showing pictures in four partner venues (Alamo Drafthouse Cinema in Staten Island, Brooklyn Academy Of Music, Bronx Museum and Museum of the Moving Image in Queens). Free panel discussions along with filmmaker conversations and dialogues Included Jia Zhangke, RaMell Ross, Barry Jenkins, Basal Adra, Yuval Abraham, Rachel Szor, Sigrid Nunez, Alex Ross Perry, Andrei Ujica, Zeinabu Irene Davis, Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich, Miguel Gomes, Payal Kapadia, Julie Loktev and Roberto Minervini all giving time and talent, along with new Asian auteurs, global documentarians, Film Comment and Indiewire journalists. Film at Lincoln Center continued its Academy Programs to support the next generation of film artists and critics and to foster a film culture embracing diverse storytelling, with mentors including Paul Schrader, Christine Vachon, Steve McQueen, Ed Lackman, Ira Deutchman, Joanne Hogg and the Safdie brothers.

In coverage of Manhattan’s six major fests, your reviewer has always sought out movies with rich origin novels or playscripts. “Read The Book, See The Movie” was once how moviegoers found their way to the movies–first through the book or play. Movie posters and newspaper ads in the first half of the 20th century often included the cover of the novel the picture was based on, Critic’s Choice reviews in the past 15 years of The Independent have occasionally started with a deconstruction of a book, followed by an analysis of the drama or documentary made from it. (Examples include Salinger, Ulysses, Orlando, Passing, Mudbound, The Lost City of Z.) The writer has always hoped for an NYFF rich enough in novels and plays to fashion an entire set of reviews in this format. The 62nd NYFF (and just in time for an 86-year-old critic) has five novels and a play with this level of excellence. Here’s the ones to first read and then seek out at a theater (hopefully) near you:

The Room Next Door: Pedro Almodóvar: 2024: Spain: 106 minutes

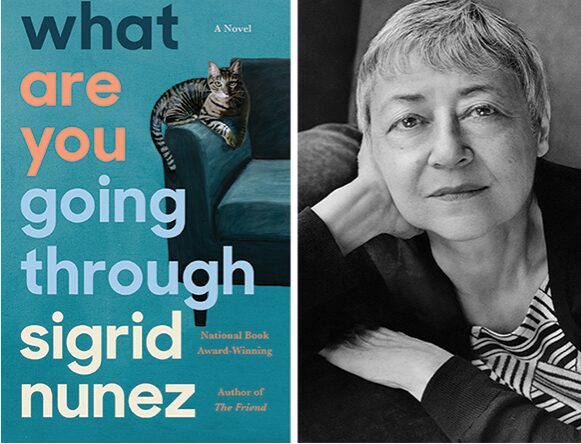

About Sigrid Nunez’s What Are You Going Through. The book title derives from Simone Weil’s supportive advice that “the love of our neighbor in all its fullness” simply means asking what she/he’s going through. Nunez, a Manhattan resident, casts herself as the narrator who’s visiting an upstate friend who’s elected to battle advancing cancer. The tumor is spreading, the woman has a year at most. At the B&B the narrator stays at, she notes a lecture being given that night by a well-known author. She attends.

The author is riveting — “white hair, beak nose, thin lips, piercing gaze.” His subject is doomsday: the rapid coming of our planet’s extinction, either through extreme climate change, nuclear holocaust, or both. He believes women should cease bearing children. He doesn’t do Q&As. He’s also her ex, “though I didn’t tell my B&B host that.” This long, depressing beginning casts a warning pale over the entire book, though Nunez has a singular skill in suppressing dread through humor. She reminds us Alfred Hitchcock believed movie audiences “should suffer as much as possible.” She quotes Sylvester the Cat’s signature burst, “sufferin’ succotash!” Nunez’s character is quirky and unpredictable, though you will never mistake her for the “crazy old lady with her bags on a park bench.”

The two women have known each other since their early 20s, working at the same literary journal. Their conversations, as well as the narrator’s own dour ruminations, swirl around lost youth and the indignities of aging. The narrator is direct in stating her distrust of “women’s fiction,” which she declares is “shunned by all male readers, and no few female readers as well.” She wants us to know she has just $1,492 in her bank account. The friend never married but has an estranged daughter 2,000 miles away, who’s reluctantly planning a visit, perhaps to say goodbye. The subject of assisted suicide is raised and dismissed — the patient decides to attempt a “hero narrative,” and the two women take a final vacation, renting a colonial style 1880s house in a New England coastal town. There the narrator meets and has a long conversation with her ex, forever on the road with his lecture tour predicting the end of the world. Then the narrator and patient sit together on the two-seater of their rented back porch, watching sunsets, holding hands.

What Are You Going Through references one novel — an unnamed psychological thriller “in the tradition of Highsmith and Simenon, set in the noirish world of 70’s New York,” and three movies: Jesus Du weisst, an Austrian documentary exploring depths of loneliness, self-doubt and sadness… Make Way for Tomorrow, a 1937 tearjerker Orson Welles called “the saddest movie ever made”… and Chantel Akerman’s No Home Movie, a documentary on the filmmaker’s last conversations with her mother. Nunez doesn’t mention it, but Akerman’s most indelible image starts that doc — a frail, slim tree being buffeted by a fierce wind for minutes on end, yet somehow clinging to its roots. A “hero’s narrative,” to be sure.

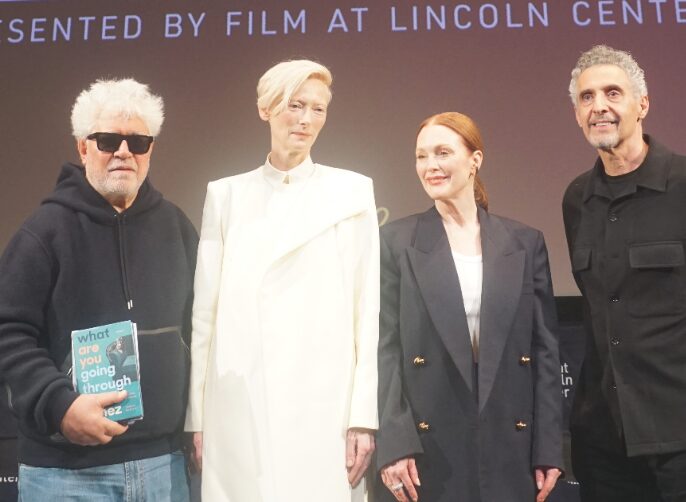

About Pedro Almodóvar’s The Room Next Door. This is the festival’s Centerpiece selection and marks the Spanish director’s 15th NYFF appearance, nine of which have been gala presentations. Almodóvar will be honored as the recipient of the 50th Chaplin Award, honoring legendary filmmakers (like Alfred Hitchcock in 1974) and actors, on April 28, 2025. The Room Next Door, his first English language feature, will open at FLC on December 20. The picture’s two marquee stars, Tilda Swinton as the cancer-ridden Martha, and Julianne Moore as her Manhattan author pal Ingrid, are perfectly cast.

As you’d expect, Almodóvar sets his Manhattan scenes between the two women with a warm and affectionate eye toward New York City. The apartment Martha comes home to after her hospital treatments is carefully furnished and comfortably appointed — it looks lived in by a woman with taste and pedigree. They meet before a movie at — where else? — Lincoln Center, right in Alice Tully Hall, its sky-high windows looking out on West 65th Street, with its corner food carts. Moore is playing the busy, successful and caring New Yorker, an easy fit. Like Swinton, she’s demonstrated through a lustrous career she can play anything, and the women embrace their roles as actors at the top of their game. One settles in, unafraid to witness how Ingrid’s going to see Martha through her last innings. We trust these artisans, as we’ve come to trust Almodóvar’s guiding hand through a lifetime of movies.

The director’s adaptation of Nunez’s novel tests that trust in multiple ways. Martha’s now a war correspondent who’s seen the horrors of combat up close. The book and the movie arguably use Damian as a stalking horse, making him the doomsayer for the planet’s coming demise via nuclear war or crushing climate change. John Turturro plays Damian, as wincing as he is convincing, laying out the end of the world to Ingrid and to us, late in the movie when Martha is closer to death. The getaway vacation home they rent near Woodstock is the opposite of an 1880’s colonial — it’s a sleekly cold contemporary with motorized blinds that rise to reveal woods. When Martha stretches out on a gray lounger in the sun, she looks like a corpse. Almodóvar also pays more attention to the concept of assisted suicide than the book does, noting that Ingrid has purchased a ‘death pill’ through the Dark Web. The movie adds a chilling investigation (not in the novel) by a snarky detective following Martha’s passing, who interrogates Ingrid relentlessly, suspecting she may have committed a crime helping her friend. It’s not a criticism to write that Almodóvar and The Room Next Door’s events are in tune with Alfred Hitchcock, who (as Nunez wrote) believed in making audiences suffer.

The Friend: Scott McGehee, David Siegel : 2024: USA: 120 minutes

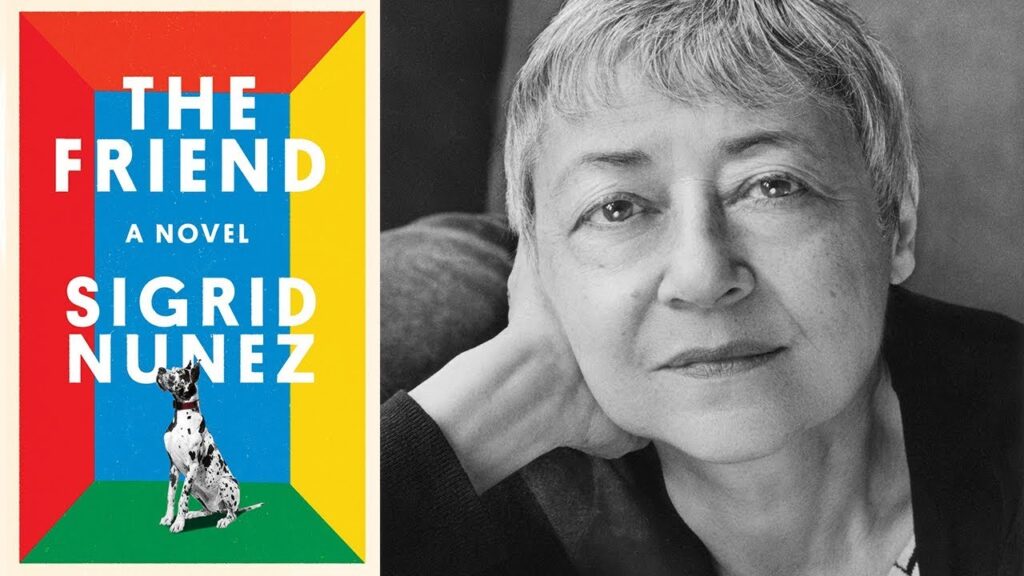

About Sigrid Nunez’s The Friend. In addition to winning the 2018 National Book Award, The Friend has just been elevated into The New York Times’ s 100 Best Books of the 20th Century. It’s little more than a slim novella in length. This time around Nunez may be imagining herself as the unnamed narrator who braids together three disparate strands of a long writing and teaching life. The first covers her mourning a lifelong fellow academic (and one-time lover) dead by suicide, a self-described “seducer and heartbreaker’” who’s left behind three wives, countless paramours and a 180-pound Harlequin Great Dane named Apollo. (The narrator first met this chap in 1974, in a class where he moved on another student who’d become his first wife.) Mostly the narrator stays nestled in her 500 square foot apartment in a tony NYC high-rise that doesn’t permit dogs. The narrator and writer’s conversations on literature, their scholarly lives, dying by “slo-mo castration,” plus related observations from his three spouses (all of whom seem to know “50 ways to tie a scarf”), dot the tale. He was the one the narrator always wanted, the guy who got away.

The second strand describes numerous students the narrator has taught over a lifetime, based on the many major colleges and university classrooms Nunez has lectured in, including The New School in downtown Manhattan. (Your critic did not know Nunez in his 33 years there as a literature and advertising professor.) Most of the narrator’s takes on her students, before the internet and since, way before Title IX forever formalized and chilled student/teacher relations, lament students’ decreasing conceptual skills as well as their poor grip on fundamentals of grammar. There’s a lot of cynical eye-rolling by the teacher toward her students, and vice versa.

The third section — which is the book’s saving grace for every animal lover — describes the narrator’s growing companionship, adoration and love for the five-year-old (and rapidly aging) Apollo, who becomes her faithful companion. This is an unabashed four handkerchief weepie of a read. One of Nunez’s singular sleight-of-hand tricks is having her narrator confess to her suicidal pal that she’s writing a novel — this novel — about their off-and-on relationship, but that she’s changed his dog from a tiny dachshund to a mammoth Great Dane. This is a significant reveal that nearly matches the book’s other saving grace, when we learn the NYC landlord will permit a support dog, thus rescuing Apollo from eviction.

Along the way, The Friend includes important references to three movies — Lilya 4-Ever, a bleak tale of a 16-year-old forced into sex work in the Soviet Union… White God, the Hungarian revenge drama in which the dogs of Budapest rise as an army against their oppressors… and Paramount’s 1953 fictionalized biography, Houdini, in which Tony Curtis plays the master magician who drowns chained upside down in a two-ton water tank, onstage, that he can’t escape from. Throughout The Friend, the narrator becomes a curious, mostly fearless, essentially solitary New Yorker with typically sharp elbows, an occasional salty mouth and a generous and abiding heart. Nunez’s novel is a rare kind of literary gem, an easy-reading gift to overcommitted urban readers and writers worldwide.

About Scott McGehee and David Siegel’s The Friend. Was there ever a saner, nicer, more patient, more accommodating New Yorker than Naomi Watts, front and center in this big-hearted, big city valentine of a movie? And has Manhattan ever look prettier and better behaved during a hectic Christmas season than what’s oh-so-carefully prepped and shown here? We haven’t seen New York City look and sound this impossibly civil and quietly grand since the early days of Woody Allen movies. While its opening scenes establishing the mystery suicide of a well-known writer may be a downer on paper, the writer is acted by an amusingly elegant Bill Murray, who promptly exits the picture. His ashes are scattered into the East River by the latest of his three wives and a boatful of admirers, and Bill won’t reappear until a magical realism scene near the end of the movie when he and Naomi suddenly turn up in his Brooklyn townhouse to discuss his life and death.

The Friend is a savvy movie full of surprises, and the biggest one is that the pal of the title isn’t Murray, but the dog his character leaves behind. And what a dog — Bing is the 180 pound Harlequin Great Dane who plays Apollo, easily stealing your heart as well as the picture. Trained by Bill Berloni, whose border collie Messi became the key witness in Anatomy of a Fall, Berloni coaxes better performances out of living, breathing animals than any animatronic created by humans.

We can’t take our eyes off Bing. He listens intently to the eulogy on the boat for his master. Promptly climbs up and takes over Iris’ bed, his sad eyes crying out for Murray’s return. When his owner fails to appear, Apollo trashes the apartment… but Iris’s devotion gradually wins him to her side, and even to her bathtub for a wash. It’s impossible not to befriend this companionable couple, especially when the building super (a spot-on Felix Solis) kindly warns Iris she’ll lose her apartment if Apollo doesn’t clear out. This is The Friend’s crisis point, and directors McGehee and Siegel maneuver it with masterly skill. As nearly every Manhattan dweller now knows, support animals go everywhere, and Iris’s helpful therapist (Tom McCarthy, another casting plus) writes the needed letters to building management. If your building’s sidewalk canopy appeared to abut Washington Square Park like the home of Iris and Apollo, you’d move heaven and earth to save it, too.

Oh, Canada: Paul Schrader: 2024: Canada: 95 minutes

About Russell Banks’s Foregone. An upfront epigraph — ”Recalling who I was, I was somebody else… somebody I love, yet only in a dream” — signals a possibly untrustworthy narrator. That’s Leonard Fife, the Canadian documentary filmmaker whose unruly life is the subject of Banks’s (1940–2023) last major novel. Fife is yet another fictional figure dying of cancer near 80, obsessed in his last hours with having a fellow documentarian and protege, Malcolm (“my Ken Burns of the north”), get his life down on celluloid while he can still tell it.

Malcolm and his co-producer wife, Diana, have 25 conventional questions, starting with why Fife fled to Canada in 1968 as a draft-dodger, and celebrating his newsy, firebrand docs on sexual abuse in the clergy and the U.S. Army’s experiments with Agent Orange. Plus how he got to know Joan Baez and — wow! — Bob Dylan. You know, stuff that festival audiences will eat up. Fife wants no part of Malcolm’s career inquiries. The failing yet forceful filmmaker has a different agenda — spilling out a lifetime of personal betrayals, abandonments and failures as a twice-married husband, father and philanderer. What he’s seeking in his last day alive is forgiveness from his third wife, Emma. She met him as a Concordia student in 1978 and later walked out on a husband and two children to marry him, becoming the mother who mostly raises the kids. What Fife wants before passing is absolution of guilt for having lived a wasted life. ‘Forgiveness’ comes out of his heavily medicated throat and mouth as ‘foregone.’

The only other people present in Fife’s luxurious Montreal apartment besides Emma and the husband/wife producers are a cinematographer, a 22-year-old female sound recorder who’s sleeping with Malcolm, and a Haitian-Quebecois nurse. Everyone questions how much of what Fife reveals is truth or invention, and why any of it matters,especially since the man’s favorite memories fasten on when he had the promise of American youth. Fife was on the road at 16 like Jack Kerouac, pulling at jugs of Thunderbird, eventually becoming a bookstore clerk and teaching assistant with a newly minted Ph.D. long before he split for Canada and learned the filmmaker’s craft. Malcolm and Julia are adamant he’s wasting what breath he has left, that movie audiences today will buy tickets to a sum-up of Fife’s provocative documentaries, not his ramshackle life. Emma doesn’t believe much of what she’s hearing, and hardly cares about the rest, convinced Leonard’s meds have zonked out his brain. The nurse insists her patient might survive longer if he’d stop beating up himself so much.

Readers familiar with Banks’s work know that his signature skill is dipping into convoluted lives and weaving long convincing tales with mesmerizing force. Continental Drift and Cloudspitter were Pulitzer Prize finalists in 1986 and 1999. The Sweet Hereafter and Affliction became major movies (the latter directed by Paul Morissey). The odd photo cover of Foregone shows Fife’s rented Plymouth having narrowly averted a cloverleaf catastrophe at 90mph, coming safely to rest off-road against foliage. Go figure.

Banks’s favorite author was the tough Chicago writer Nelson Algren, famed for Man With the Golden Arm and Walk on the Wild Side, whose movie adaptations arrived with swagger that pushed boundaries. And the book Banks wrote before Foregone, a volume of travel essays titled Voyager, includes a deconstruction of the author’s four wives and marriages, two of which bear a startling resemblance to Fife’s two failed marriages (to a Florida teen and a Richmond swell) as the doc maker describes them. The questions linger: Is Foregone a stylized auto- or metafiction? A disguised memoir? And of course, will anyone go see a movie made of it?

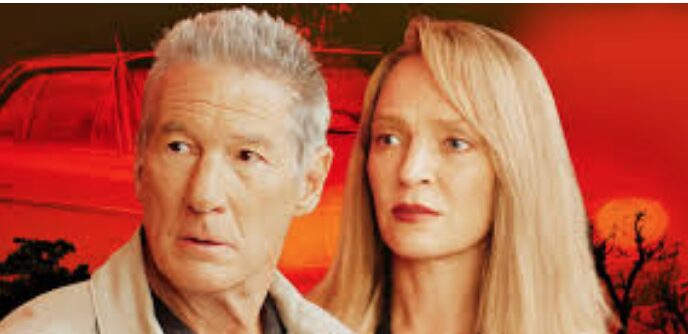

About Paul Schrader’s Oh, Canada. The movie’s narrative of Fife’s early life matches the novel with remarkable fidelity. Thus it’s essential that we understand and believe that Richard Gere’s much-married father wants forgiveness from Uma Thurman’s measured and outwardly neutral wife. Gere has to project this longing not just with the right language in his director’s adaptation, but with the same adamant force as Banks’s fierce character. It’s not enough for Gere’s Fife to brush aside his filmmaking career and accomplishments as he does in the novel. For the movie to work, we have to believe he dies hoping for salvation as a flawed husband and dad.

Schrader knows Russell Banks’s work well, having adapted the painful Affliction (1997), which won James Coburn an Oscar. Six years ago, the director solved the kind of challenge posed in adapting Banks’s Foregone, with his unforgettable drama First Reformed. In that film, Ethan Hawke played an alcoholic pastor dying of stomach cancer in an upstate church. When a parishoner commits suicide over climate change and the pastor learns his church is indirectly contributing to it, he elects to end his own life — first wrapping his bare chest in barbed wire that bleeds through his clerical robe. It’s one of several startlingly vivid scenes Schrader invents in the film, including a sky-bound levitation with Hawke soaring through the clouds, that visually dramatizes the protagonist’s final moments. Other directors like Darren Aronofsky in The Whale and Gus Van Sant in Last Days have similarly staged their lead character’s endgames by visualizing ‘souls’ rising out of bodies, presumably toward heaven.

Richard Gere at 76 certainty looks the part and gives Fife everything he’s got, so one issue is whether Schrader has written him enough. If you’ve read Foregone, it’s more likely you’ll agree he has. Another potential sticking point is whether the family and filmmakers surrounding Gere’s Fife are emphatic enough in trying to wave him off what they perceive is a colossal pity pot, and use his waning energies to champion the acclaimed docs he’s made. No one in the household wants to hear this dying man’s confession.

Schrader’s screenplay doesn’t give Malcolm (Michael Imperioli) and Diana (Victoria Hill) the obsessive, single-minded commercial focus of their literary counterparts, who beg Fife for a doc that first and foremost will make them money. Schrader hasn’t written this couple nasty enough. Uma Thurman’s Emma has similarly been neutralized, and perhaps to make up for this, Schrader double-casts her as the wife of an academic colleague who has a sexual interlude with Fife. His two earlier wives (Kristine Froseth and Penelope Mitchell) are barely developed characters, as are the abandoned sons (Sean Mahan and Zach Shaffer). As the younger Fife, Jacob Elordi works hard but could use a lot more freewheeling life on the road. At 95 minutes, Oh, Canada had the luxury of time to make more of Fife’s meanderings and philanderings worth remembering… and worth the documentary Malcolm clearly won’t make.

Nickel Boys: RaMell Ross: 2024: U.S. : 140 minutes

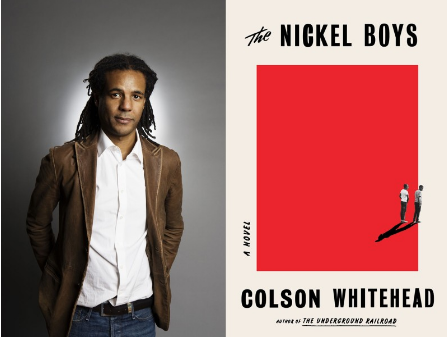

About Colson Whitehead’s Nickel Boys. Whitehead’s gift as a word-by-word precisionist helped win him the Pulitzer Prize for his magical realism novel The Underground Railroad. Here he pens a precise tale of biographical realism, based on a Black youth’s coming-of-age in a reform school modeled after the Dozier School for Boys, operational for 111 years in Mariana, Florida. We follow Elwood Curtis, a bright youngster raised by a loving grandmother. Elwood learns to read comics and magazines as a clerk in a tobacco shop, along with James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son, Hardy Boys adventure books and one sample volume of an encyclopedia.

The single vinyl LP he plays over and over is the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr’s 1962 sermon at an LA Baptist Church. In high school Edwood acts a slave on a sugar plantation who runs away to join the Union Army. At graduation, the tobacco shop owner gifts him with a fountain pen. Elwood joins a picket line at a segregated movie theater, hoping to see Marlon Brando as The Ugly American. On his way to a free college north of Tallahassee, he thumbs a ride in what he can’t know is a stolen car, which is pulled over. In a courtroom, all of Elwood’s potential and promise is sentenced to the Nickel Academy.

Nickel has the outward appearance of a rural college campus — trees, horse stables, sports fields and courts, red-brick architecture. There’s a wall but no barbed wire fencing. The curriculum is partly lessons in the classroom, partly work details manufacturing the red bricks Nickel exports to the world. Blacks and whites bunk in separate dorms. Students are promoted annually as Grubs, Explorers, Pioneers and Aces. But the texts are discards from white schools, filled with racial obscenities. And there’s a Beating Room in a ‘White House’ where Elwood gets his first bloody lessons from a three-foot strap nicknamed Black Beauty that shreds pieces of his back. He learns the guards are tasked to brutalize any student who steps out of line. One older student is Turner, who’s been a pin setter in a bowling alley in Houston. Turner’s 20 and will become Elwood’s protector and soul brother.

The two young men get to know each other doing yard work, painting dorm windows and cleaning up rubbish in a downtown park. They don’t much care whether John Kennedy or Richard Nixon will be elected president. Watching boxing matches, the wily Turner gives the quieter Elwood lessons in the art of self defense. (You may be reminded of Mario Vargas Llosa’s first 1966 novel, The Time of the Hero, a pulpier, more urgent study of cadets in a Lima military academy, with its similar mix of hazing, confinement and boredom.) What sparks Nickel Boys’s long middle sections are the author’s projections into a future life on Harlem streets that Turner is preparing Elwood for — a life Whitehead has already superbly explored in his noirish novel Harlem Shuffle and its sequel, Crook Manifesto.

The underlying argument running through Nickel Boys is that the school’s cruelty and rotten corruption becomes, inevitably, a training ground for survival on any big city’s mean streets. Elwood continually cushions the whippings he endures with Dr. King’s mandate to “walk the streets of life with this sense of dignity and this sense of somebody-ness.” Whitehead writes that “perhaps that was the afterlife that awaited (Elwood)… with an eternity of oatmeal and the infinite brotherhood of broken boys.” He provides the website of Dozier survivors telling their own stories in their own words: the officialwhitehouseboys.org

About RaMell Ross’s Nickel Boys. In 1946, Robert Montgomery directed and starred in an adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s fourth novel, Lady in the Lake, originating a technique advertised as “a startling method of storytelling, a milestone in movie-making — and you!” The camera point-of-view becomes Montgomery — that is, all the characters speak to the camera. Bad guys slug the camera, the femme fatale embraces it. Viewers have endlessly debated the camera-as-protagonist POV ever since. Some call it a true innovation in cinema, others decry it as the worst storytelling gimmick since Cinerama and 3-D.

Ironically, MGM distributed Lady in the Lake, just as Orion/Amazon MGM is distributing RaMell Ross’s Nickel Boys, which is mostly made the same way as Lady in the Lake. For nearly half the movie, the camera is Elwood (Ethan Herisse). Then the camera becomes Turner (Brandon Wilson). Occasionally we see both young men together in the 1.33:1 postage-stamp ratio that honors its 40’s predecessor. Whether you celebrate Ross’s subjective use of POV as revelatory or find it annoying beyond words, it makes Whitehead’s novel into a highly staged piece of artistry.

Ross and his co-adapter Joslyn Barnes follow the novel closely — nearly all the key scenes starting with Elwood’s arrest are preserved, including a telling conversation between two Nickel survivors in an uptown NYC bar years later in the 1960s. Elwood’s beatings are heard but not shown. Herisse and Wilson are adroitly cast, both are persuasive (often with just their off-camera voices) and each projects vulnerability along with an unquenchable desire to survive. As Hattie, Elwood’s grandmother, Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor (memorable as Isabel Wilkerson in Origin) provides heartfelt support. The production design, complete with alligators slithering around Nickel as well as its adjoining town, properly accentuates the drama’s bare-bones classrooms and dorms. Ross’s use of archival footage helps ground the viewer. Jomo Fray’s lensing is much harder edged than his gentle southern world of All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt, and the music by Alex Somers and Scott Alario often has a harsh, off-putting originality that’s in tune with Ross’s unusual POVs.

In a press conference the day of its premiere, the director was upfront about its Lady in the Lake origins. And in a Film Comment interview, he describes his POV as he used it in a 2018 documentary, Hale County This Morning, This Evening, as “sentient perspective.” Nickel Boys is, make no mistake, an art film of the first order, which is no doubt why NYFF honored it as its Opening Night.

Queer: Luca Guadagrino: 2024: Italy: 135 minutes

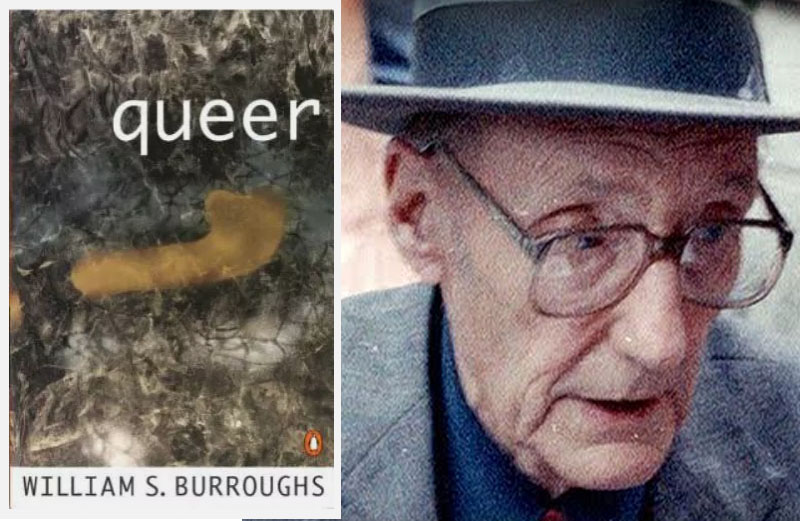

About William Burroughs’s Queer. Imagine what pulp magazines in the 1940s used to call a novelette — a long short story — that’s a wicked cross between novels by Joseph Conrad (Outcast of the Islands) and Malcolm Lowry (Under the Volcano). Burroughs casts himself as William Lee, the pseudonym he used in authoring his first paperback original, Junkie. In this sequel, Lee is another cross-addicted, gay drug addict who’s committed to cutting back his more serious addictions into a manageable daily diet of gin, cognac and rum Cokes. The setting is Mexico City in the early 1950s, where Burroughs resided, carrying a pistol and accidentally shooting (and killing) his second wife. It was “a cheap place to live, with fabulous whorehouses and restaurants, cockfights and bullfights, and every conceivable diversion.” When he died in 1997 at 83, Burroughs’s final writing fragment admitted that “love is the most natural painkiller.”

The very masculine Lee closely resembles the former British counsel of Lowry’s 1947 novel, a chronic alcoholic in a village just outside Mexico City who’s desperately trying to recapture the love he’s lost in his divorce, and finds only In the bottom of the bottle. Burroughs surely read Lowry’s novel, even copying the counsel’s dressy linen suits and fedora. Like the counsel, Lee has money and intelligence, but what he’s really pining for is a husband, or at least a lover among the countless skinny native boys, barely of age.

Lee’s dilemma is akin to the character of Willems in Conrad’s second novel, set in the 1880s in the Dutch Indies — we follow the disintegration of a successful South Seas trader who marries a native woman but falls in love with a second, younger woman from a different tribe, and the revenge that one woman exacts. Outcast of the Islands, Under the Volcano and Queer all play out in exotic, primitive societies and cultures at the edges of civilization, and all three consider men whose moral compasses are fractured, and whose hearts are broken by substances or lovers. The first two are classics of world cinema and among the best pictures Trevor Howard and Albert Finney ever starred in.

Lee finds his femme in Eugene Allerton, a louche who’s emerged from World War II without a plan. “He was not queer enough to make a reciprocal relationship possible,” Burroughs writes. “Lee’s affection irritated him. Like most people who have nothing to do, Allerton was resentful of any claims on his time. He had no close friends, he did not like to feel that anybody expected anything from him.” The two men have sex on a regimented schedule, and the sex is not explicitly described. Queer wasn’t published until 1985, and Viking Penguin’s cover illustration is a murky painting by Burroughs of his genitals. The painting promises far more than the novel delivers.

What it previews is some of the author’s tongue-twisting language that will inform Naked Lunch, like this: “In the dark theater Lee could feel his body pull toward Allerton, an amoeboid protoplasmic projection, straining with a blind worm hunger to enter the other’s body, learn the feel of his viscera and genitals.” The men journey by train, bus and boat to Guayaquil, Las Playas, Salinas, Quito, Babahoyo, Ambato and Puyo — deep into Ecuador’s heart of darkness. Neither end up as badly as Lowry’s counsel, whose body, riddled with bullets from police chiefs, is tossed down a ravine along with a dead dog.

About Luca Guadagnino’s Queer. Any fan of the aptly named industrial band Nine Inch Nails, starting in 1989 with Pretty Hate Machine, has surely been waiting for Trent Reznor, along with his film scoring partner Atticus Ross, to get their hands on the right booze and dope movie. Man-oh-Manischewitz could they do a lot of damage. It’s been a long wait and we’ve patiently waded through the hair-raising soundtracks of jittery items like Gone Girl, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, The Killer and Guadagnino’s Bones And All. Finally the right dope author and sex title, with two sterling actors in place in the right sleazy 50s Mexico City setting, have stumbled into place. Want to get high in your theater seat without a smidgen of wine, weed or the psychotropic drug, yage? Trent and Atticus, led by a Reznor original, “Vaster than Empires,” plus music by Harry Nilsson, Nirvana, Prince, Love Is A Drag, Nat King Cole, Sinéad O’Connor, Benny Goodman and so many more, are here to serve you. You’ll even hear Stan Jones’s cowboy favorite, “Ghost Riders in the Sky.” Damn near every scene with music — and most scenes have some musical something tugging at you — is a blissout.

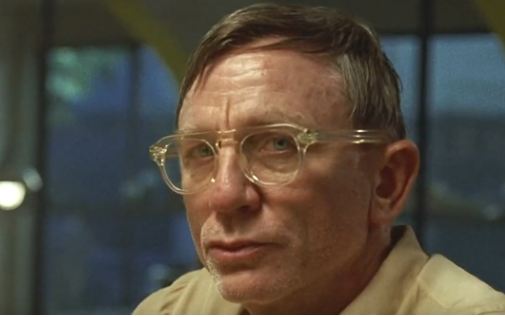

It takes less than two minutes when he comes on screen, weaving his way unsteadily from bar to bar in search of his next sex partner, to forget Daniel Craig ever played James Bond. In his slouch hat, cloudy glasses and soiled suit that barely conceals a loaded revolver in his waistband. Craig’s Lee is a marvel of intellectual posturing. He’s an expert at pretending he’s not dying for his next drink, fix or hookup. Like Burroughs in this key phase of his life, Lee is cross-addicted to liquor, heroin and men’s groins — they’re what he lives for. Director Guadagnino and his co-writer Justin Kuritzkes etch scenes of the novel in all their luridly lush emptiness. You can’t watch a long closeup scene of Lee longingly heating his junk in a spoon and then injecting it without flashing back to 1955 and Man With the Golden Arm, in which Otto Preminger dared to defy industry prohibitions by filming Frank Sinatra doing the same prep, though even Preminger shied away from showing him shooting up.

As Gene, Drew Starkey is ideal, the very essence of a handsome, listless vet who seems permanently stuck in World War II ennui. (Ditto Jason Schwartzman, playing another drunk at the same hotel bar.) Gene is game to be seduced from time to time, but he doesn’t want to be possessed except in bed. Their couplings are far more explicit than anything in the novel. Gene lazily joins his paying patron on a trip into the jungle to score some yage, or ayahuasca, known by native tribes for its telepathic potential. There they encounter a botanist surrounded by snakes who could have stepped out of a Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan movie, played with gusto by Lesley Manville. One could reveal more tricks Guadagnino delivers as often as Reznor pulls up a tune to accompany them, but this appraisal is enough of a tease. Since Queer is impossible to find in any New York City used and rare bookstore, as it’s always sold out, you may have to settle for the movie, which ain’t a bad idea at all.

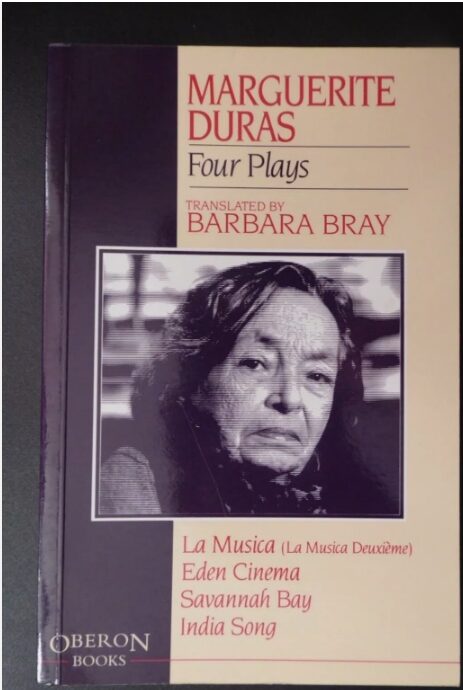

La Musica: Marguerite Duras, Paul Seban: 1966: France: 86 minutes

About Marguerite Duras’s La Musica. The setting for Duras’s one-act play, published in 1965 by Editions Gallimard, is an entrance hall/lounge in the Hotel de France. The play will become Duras’s first film. The bright lighting will gradually dim and pinpoint Anne Marie (known as She) and Michel (known as He). They’ve been divorced for two years and are meeting by accident in the hotel they lived in before purchasing their home.

He’s waiting for a train to Paris where he’s meeting his new lover. She’s preparing to move to America, to remarry. It’s an awkward encounter, and they first chat about where their furniture will end up. But the conversation shifts to the cause of their divorce, which was mutual infidelity. This subject among others made Duras widely acknowledged as the first lady of French letters during the second half of the 20th century.

Both agree their marriage as very young adults was a “hotel honeymoon” that rapidly became a boring homebound hell. “We should have stayed in this hotel,” s/he agree. And then he went to Paris on business where he fell in love with someone else. While he was away, she started an affair.

“It’s just terrible, the first time you’re unfaithful,” she says. He was suspicious and had her followed, to the movies, to the races, but she was always alone. “You’re always alone when love begins to languish,” she admits. He thought about killing her — “I couldn’t bear you being unfaithful, and all the time I was unfaithful myself.” S/he admit they each found “miserable happiness” with new shadow lovers.

Suddenly her former husband wants her back. “Don’t go to America,” he pleads. “Stay in France.” But it’s over. “Look at me,” she asserts, “I’m the only woman who’s forbidden to you. We’ll never meet again, except like here, by chance.” La Musica is a two-hander in the mode of countless separation/divorce encounters. It was Duras finding her voice as a playwright much in the mode of Harold Pinter, whose couples took a long time (and even longer stage pauses) to wound and be wounded. With the right actors, her brief play can come to bristling life.

About Marguerite Duras and Paul Seban’s La Musica. Delphine Seyrig (1932–1990) was best known for many years as the elusive, enchanting beauty who wandered through Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad in 1961. The influential film journal Sight and Sound gave her legacy a huge boost two years ago when it named Jeanne Dielman, 23, a three-hour slow cinema study of a Paris prostitute made in 1975 by Chantal Akerman, in which Seyrig starred, as the greatest movie of all time. Robert Hossein (1927–2020), through an equally fertile career, was a handsome, intense leading man who partnered leading ladies from Brigitte Bardot and Sophia Loren to Marina Vlady and Audrey Tautou. La Musica’s hotel is set and photographed in and around Évreux by Sacha Vierny, who lensed Marianbad. Seyrig and Hossain are Ideal translators of Duras’s text, often acting line for line from her play. One couldn’t imagine more engaging French casting.

Because the one-act play runs considerably less than 86 minutes, Duras has introduced another character upfront, an early 20’s Parisian, unnamed, played by Julie Dassin (daughter of director Jules Dassin). She’s not a pickup but she’s in the midst of a breakup, and she latches onto the divorced husband outside the hotel and pours her heart out to him. They take a drive into the countryside and talk and talk, while we sit on our hands. This is called padding — the half hour they fill up is a time filler, no more and no less. When Julie departs the movie, Duras’s play begins and holds intact.

There’s a cinematic lesson to be learned from this, and the director who’s now teaching it is none other than Pedro Almodóvar. Twice now Almodóvar has had the bright idea that a fully developed drama can be told In half an hour. He did it in 2020 with his 30-minute adaptation of Jean Cocteau’s 1928 play, The Human Voice, starring Tilda Swinton, who’s mostly on the phone being dumped by her lover. The inventive director followed it up last year with Strange Way of Life, a two hander gay western based on a novel by Tom Spanbauer. That starred Ethan Hawke and Pedro Pascal and ran 30 minutes. The New York Film Festival showed them both, and not as shorts, but right along with features. In an era In which so many viewers’ attention spans are shredded, Almodóvar may have hit on a significant way audiences will come to recognize a “feature length drama” as a much shorter feature length drama.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in DOC NYC, November 13-December 1.

Regions: New York