Tribeca Festival June 4-15

A late congresswoman delivers this 24th edition’s most urgent message

Caution: This opening essay history is one movie critic’s personal perspectives and frustrations on what used to be the Tribeca Film Festival and how it’s changed.

In August, 2019, The Hollywood Reporter announced that “Lupa Systems, the new venture company led by former 21st Century Fox CEO James Murdoch, has acquired a majority stake in Tribeca Enterprises, which puts on the annual Tribeca Film Festival.” The plan put James Murdoch effectively in partnership with festival co-founders Jane Rosenthal and Robert De Niro.

You would recall that the festival’s original mission statement was to “spur the economic and cultural revitalization of lower Manhattan” so severely weakened by 9/11. New York City has regained much of its pre-2002 vitality because its two essential institutions —its public schools and Broadway—are back up and running reasonably well. But wide swaths of the city have never fully regained their robust economic vitality. And so the theaters Tribeca rents out this year—on Second Avenue, on West 23rd, in its Chambers Street performing arts center and its Varick Street home base, on lower Broadway as well as on upper Broadway—draw neighborhood residents as well as a multitude of flyover city visitors. People rarely come out for just a movie in trendy neighborhoods. Tribeca isn’t a destination festival because it’s been too spread out from the get-go.

By 2022, the Tribeca Film Festival had shed “Film” from its name and became known as the Tribeca Festival, as it is today. While still being led by CEO Rosenthal and De Niro, the two movie makers have found themselves presiding year after year over massive conglomerations of retrospectives, talks and panels, tv (premieres, episodes, pilots, series), music concerts, games, podcasts and the latest immersive media, with all its augmented and virtual reality, and now AI. Plus, to be sure, a growing list of branded sponsorships. Make no mistake, The Tribeca Festival. like nearly every one of Manhattan’s 40+ film festivals, is a for-profit enterprise.

(This critic’s modest recommendation for next year’s 25th Tribeca gala anniversary would be a revival showing of the best Rosenthal/De Niro collaboration ever, The Good Shepherd. He directed, starred and co-produced with Rosenthal this stunning, underrated 2007 spy thriller on the origins of the CIA, abetted with an all-star cast that rivals all three editions of The Godfather. It would be a hands-down Critic’s Choice.)

Tribeca has moved its annual festival from April to June, thus shouldering its way in before, alongside and after locally generated Manhattan and Brooklyn festivals that include theaters running features exclusively from Africa, Italy, India, Japan and Asia.

The result has been a crush of competition just as schools close for the summer. Perhaps wanting to demonstrate that ‘the more things change, the more they stay the same,’ Tribeca has increased its already daunting load of dramas, documentaries and shorts. The vast majority don’t have distributors, so nearly every drama, doc and short hires a publicist to attract any kind of coverage. Tribeca continues its longtime practice of ‘embargoing’ (read ‘forbidding’) long-form reviews on all motion pictures until their public premieres—a limitation that’s always hobbled critics and increasingly has been adapted by other fests, filmmakers, distributors and even individual theaters. Awards are given by audiences as well as industry professionals assigned to specific categories.

The common wisdom is that independent film has never been so imperiled by the impacts of streaming, Covid, industry strikes, looming tariffs, and the ever-present dangers of piracy. (One Tribeca critic’s screening in a vast theater to half a dozen viewers was monitored by two suited-up representatives from the distributor, whose sole purpose in being there was to study a handful of critics for any newly styled glasses now equipped with mini cameras.) These are all facts. Another dire truth is that more Manhattan festivals are drowning in movies like Tribeca. Most of these films are dead on arrival, awaiting exile to some lost corridor of indie hell. At Tribeca, there was no way one critic could wade through more than a sliver of the fest’s daily activities and movies.

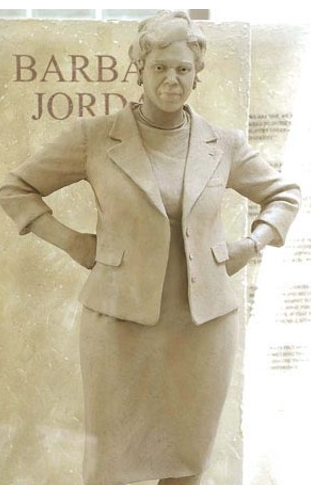

And so this viewer has elected—for the first time in fifteen Tribeca reviewing years and more out of frustration than anything else—to share just one piece of one component of this 24th Tribeca edition. It’s a feature-length doc running less than two hours, and structurally it’s a familiar, even conventional narrative of a deceased Black woman’s life and work in politics, 1936 to 1996. It features simple, direct camera work, a touch of animation here and there, rat-a-tat precision editing, a hardworking music score that aligns perfectly with a fast-paced narrative. Plus Alfre Woodard’s calm, measured narration framing the many talking heads (mostly family and friends, academics and legislators) who served with this remembered politician.

Everyone on screen and off builds a standalone biopic of a pioneer Black patriot elected to congress in 1972, now reporting from the grave to America in these life-altering times. She speaks with gravity, insight and grave concern in equal measure. She marched for freedom, practiced DEI before anyone thought to link these democratic essentials together, and took pride in living with another woman nearly all her adult life. If you read the following summary of her time on earth in a summer of ‘25 that’s already heating up in new and frightening ways, you may have to find your way to her movie on PBS, if not in a theater near you. That’s ample reward for this critic. Take heed.

The Inquisitor: Angela Lynn Tucker: USA: 2025: 98 minutes

“Today I am an inquisitor. My faith in the Constitution is complete, it is whole, it is total. And I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator in the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution.” There she is, boldly speaking her mind in the first minute of this documentary. The context of Barbara Jordan’s now-legendary 1974 address will come later, when we find her on the House Judiciary Committee, considering articles of impeachment against U.S. President Richard Nixon. The president was accused of approving and concealing the burglary by five men of files from Democratic party headquarters in DC’s Watergate hotel. Seated next to Jordan before they vote is New York senator Charles Rangel, a close colleague who died at 94 several months ago. Jordan and Rangel both vote yes and Nixon shortly becomes America’s first president to resign in office.

Jordan was raised poor in a loving Houston family during the post-Depression 1930s. Her mom was a maid and her dad worked in a warehouse while studying to become a Baptist pastor. An all Black debate team at Texas Southern University sparked Jordan’s natural ability to argue on her feet, defeating debate teams from Yale and Brown. She earned her law degree from Boston University School of Law in 1959, then returned to Texas as one of two Black attorneys in the entire state. Lyndon Johnson first spotted her as a volunteer in the Kennedy/Johnson campaign, sensing a firebrand who’d get out the vote in Black Houston churches. He liked that Jordan positioned herself as “a helping force, not a disruptive force,” and remembered comments like “Blacks can be as competent in the boardroom as we are in the bedroom.” Not every Texan took to her, and she was mocked as “looking like Aunt Jemima and talking like Bobby Kennedy.”

After two unsuccessful runs for the Texas senate, Jordan won in ‘66, becoming the only woman among 31 white men, noting “now we have legislators that serve people, not cattle.” (Ooh, this was a debate with attitude!) Johnson, who’d become president following Kennedy’s assassination, boosted her onto federal committees where she introduced over 50 successful bills affecting core issues like housing, wages and hate crimes. She helped expand the earlier Voting Rights Act to include language minorities, while clamping down on corporate price fixing. The U.S. president became Jordan’s most important mentor. In ‘72 she won election to the U.S. House of Representatives, the first woman to represent Texas.

Following Nixon’s resignation, Jordan gave a blistering keynote address at the ‘76 Democratic convention in Madison Square Garden. There she was viewed as a potential running mate for Jimmy Carter. She really wanted to be Carter’s attorney-general. Select nuggets from her speech:

“Many fear the future. Many are distrustful of their leaders and believe that their voices are never heard. Many seek only to satisfy their private work, private interests. But this is the great danger America faces, that we will cease to be one nation and become instead a collection of interest groups, individual against individual, each seeking to satisfy private wants. ”

“In 1976, are we to be one people bound together by common spirit, sharing in a common endeavor, or will we become a divided nation? For all of its uncertainty, we cannot flee the future. We must not become the new puritans and reject our society. We must address and master the future, together. It can be done if we restore the belief that we share a sense of national community, that we share a common national endeavor, it can be done. There is no executive order. There is no law that can require the American people to form a national community. This we must do as individuals. And if we do it as individuals, there is no president of United States who can veto that decision.”

“I ask you that as you listen to these words of Abraham Lincoln, relate them to the concept of a national community in which every last one of us participates. ‘As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master.’ This expresses my idea of democracy.’ Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy. ”

Carter picked another vice president and another attorney-general.

By this time, having moved to Austin from Houston, Barbara had met and fallen in love with Nancy Earl, a white educational psychologist, on a camping trip. They bought a five acre plot and built a home to live together. Knowing her partner had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, diabetes, and eventually leukemia, Nancy moved with Barbara to Washington. when Jordan was elected a state senator. Though she’d be confined to a wheelchair, Jordan never publicly acknowledged any of her illnesses nor her life companion. Nearly everyone outside the LGBT community assumed Earl was her daily caregiver, which she did become. Only Jordan’s declining health prevented President Bill Clinton from nominating her to the Supreme Court. Instead she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In ‘78 she returned to Austin and the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, joining the University of Texas faculty as an adjunct professor. She began by leading a seminar on government to fourteen grad students. Though Jordan defined herself first and foremost as a patriot, what’s carved at the top of her headstone is TEACHER.

And so your critic/teacher/journalist can’t help but note with growing alarm yet another loss of freedom cited in yesterday’s New York Times story (6/19/25) headlined “Texas Law Would Roll Back Freedom of Speech Protection on Campus.” Jeremy Peters reports that “Republicans in the Texas Legislature–including some who helped write the 2019 law–did an about face earlier this month approving a bill that would restrict how students can protest.” The Texas bill would “greatly expand the state’s influence over ‘expressive activities’ on campus, defined to include what students wear, how much noise they make and the hours of the day when expression is allowed.”

The Inquisitor is a biopic for our times. Director Angela Lynn Tucker is a native New Yorker, a Wesleyan graduate with an MFA in Film from Columbia University. Her work includes Belly of the Beast (dir. Erika Cohn); The Trees Remember, a Webby-winning branded series; and A New Orleans Noel starring Patti LaBelle. One of The Inquisitor’s most winning moments comes near the end in Jordan’s home in Austin, surrounded by Nancy and friends plus a pianist who knows from songbooks. Barbra still has a clear alto from her churched childhood and has a way with these haunting lyrics:

“THEY CAN SEARCH THIS WHOLE WORLD OVER,

THEY’LL NEVER FIND A GAL AS SWEET AS ME.

WHEN I DIE PLEASE BURY ME

IN MY WHITE STETSON HAT

THEN PUT A TWENTY DOLLAR GOLD PIECE

ON MY WATCH AND CHAIN

SO THE GANG WILL KNOW I DIED STANDING PAT.”

This concludes critic’s choice. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 63rd New York Film Festival, September 26-October 13.

Regions: New York City