Everything Before Was Prologue: The Radical Cinema of Barbara Hammer

Barbara Hammer spent decades filming lesbian bodies and desire, insisting audiences feel what they’d largely never seen. A pioneering experimental filmmaker, she created over 80 films that made queer life visible when very few others would. This year, “Barbara Forever,” premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, telling Hammer’s life story through her own voice and archive.

Director Brydie O’Connor built the film entirely from Hammer’s personal archive — home movies, outtakes, film clips and candid moments — subsequently narrated by Hammer herself. In the film, O’Connor refuses to follow a chronological order, cutting from young Barbara to old and back again within a single sequence, an approach that mirrors Hammer’s own experimental filmmaking. Time zigzags, letting Hammer shape her own legend and ensuring her voice remains central, even after she’s gone — the filmmaker passed away at age 79 in 2019. This radical openness is Hammer’s filmmaking philosophy made visual.

Hammer appears fully nude in the film’s opening moments, her body unguarded, the camera lingering on her movements. It’s a disarming welcome. As a viewer, you become acutely aware of your own gaze as her narration draws you closer, making you feel more like a confidant rather than an observer.

“If you’re not represented by one of your group, you will be misrepresented,” Hammer declares in the film. She lived by that principle from the moment she understood what it meant to be a lesbian, a word she first heard at 30 in a feminist consciousness-raising group. She claimed it, acted on it, and rewrote her life.

Hammer calls her 1974 film “Dyketactics” the first lesbian lovemaking film made by a lesbian, conjuring not just bodies but sensation: the camera panning across skin, light dappling flesh, editing pulsing with tactile rhythm. When museums like the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA ) repeatedly rejected her work, Hammer’s response was strategic persistence. She flooded the world with images that could not be ignored, making film after film. In the 1980s, her work began screening at MoMA and the Whitney Museum of American Art, the very institutions that had, at first, shut her out.

“A lesbian film is not going to follow a traditional story,” Hammer preached — a rule which is embraced by the documentary. “Barbara Forever” begins with its protagonist at 30, the year she came out. This locates her true beginning at that pivotal age, when she could finally name herself. This structural choice rejects the assumption that life begins at birth. For Hammer, life began when she gained autonomy through language and community. Everything before was prologue.

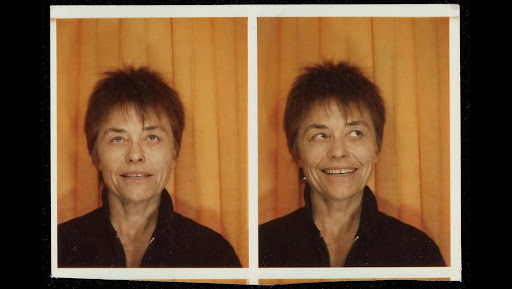

Credit: Barbara Forever LLC

That choice reverberates through the film’s most striking moments. In one sequence, Hammer walks the Hollywood Walk of Fame, filming the stars embedded in the sidewalk. Her voice narrates with giddiness as she searches for lesbians, “Could she be one?” Her lively spirit makes the erasure of lesbian identity all the more devastating.

Star after star, name after name, none of them hers, none of them celebrating queer lives. What begins as a performance turns poignant and strange. She’s highlighting an emptiness, the names that should be there but aren’t. Yet in capturing that absence, she’s already filling it, her camera creating the visibility the Walk of Fame denied.

Part of the film’s intimacy comes from Hammer’s own camera work. Many of her subjects were lovers, which can be seen in how they meet the lens. They’re not performing for posterity, but rather looking at the person they love, who happens to be holding a camera. The direct gaze transforms the power dynamic; the camera extends Hammer’s presence rather than creating distance. The images capture mutual witnessing, not observation. O’Connor honors this intimacy by staying out of the way; there are no talking heads or outside voices, just Barbara.

Hammer’s voice evolves across time. Editor Matt Hixon weaves together recordings from all stages of her life, jumping from youthful exuberance to the rasp of age. In moments, time collapses: Hammer electric and exposed, then older, slower, but just as unflinching. The film is a life shimmering across the screen at once. Ambition and defiance linger in a voice grown fragile. When Hammer says she wants to exist forever, the heaviness of her wish is palpable. Time and voice layers overlap. Fragments somehow cohere into something whole, a life fully lived, marked by its end. That layering creates the film’s emotional core, not tragedy but fulfillment, sparking a reckoning with our own mortality and what we hope to leave behind.

“Barbara Forever” creates a sense of urgency in every frame: the whir of the projector, the grain of old film stock, the crackle of Hammer’s voice narrating her own archive. There’s a raw intimacy to the experience, as if you’re thumbing through a private scrapbook or listening to a late-night confession. The film invites you to witness Hammer’s journey and feel the stakes of being seen; to remember the ache of wanting images of your own life reflected back at you.

In 2006, Hammer was diagnosed with stage III-C ovarian cancer. She lived with it for thirteen years, her body slowly failing while her commitment to her work remained absolute. Where she once filmed multiple days a week, she eventually could only manage one. But she kept going still, continuing to create. To stop filming would mean surrendering what had always sustained her: looking, witnessing and insisting that she existed. Even in the face of death, her vision stretched past her own lifetime. She wanted every reel, every scrap of B-roll, everything she’d filmed preserved for the next generation of filmmakers.

The art of dying, as Hammer said, is the same as the art of living. The film’s closing is devastating in its simplicity: a montage of Hammer walking up to the camera and turning it off, repeated across different eras of her life, again and again, the routine end of a shoot. Then, after the final time, the screen goes black.

“Barbara Forever” earned the Jonathan Oppenheim Editing Award at Sundance, with the jury praising editor Matt Hixon for “forming exquisite connections between history and biography, art, and life” to give “a pioneering figure in queer experimental filmmaking her rightful due.” At the premiere, director Brydie O’Connor shared that Hammer once said premiering at Sundance, after 25 years of making work, finally made her feel like she’d “made it.” Presenting ”Barbara Forever” at the same festival decades later, O’Connor admitted she felt the same way. It’s a fitting full circle, Hammer’s story returning to the festival that recognized her, told through what O’Connor calls a “queered chronology,” a structure that honors Hammer’s vision for lesbian film: refusing rules, collapsing time and beginning with what O’Connor beautifully termed “the lesbian birth.”

When Hammer’s partner, Florrie Burke, spoke after the screening, she paused, visibly moved. “Barbara would have loved this film,” she said, describing how it felt both wonderful and difficult to see Barbara represented this way. That dual feeling, wonder and grief, celebration and loss, is what “Barbara Forever” holds space for. She wanted to exist forever, and through O’Connor’s curation of her voice, her images, her relentless insistence on being seen, she does. The camera is off, the screen dark. But Barbara Hammer remains, still making us feel what we might never have otherwise seen.

Regions: Park City