Best of 17th Annual Tribeca Film Festival

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw Salutes Tribeca’s Female-centric Narrative Dramas, Docs, and Shorts

For the moment, put aside Tribeca’s round-the-clock menus of virtual reality, games, TV show previews, talks, storyscapes, virtual arcades, artists’ and festival and audience awards. The recurring news that ran like a fever from April 18-29 through downtown Manhattan movie lines was this: 46% of Tribeca’s 99 feature film premieres were directed by women. Imagine. Nearly half of a major festival’s main slates had a female helmer. Plus 26 of TFF’s 65 shorts directors were women.

This was the killer buzz from day one among the scores of young women who dominate the festival’s crew and staff every year. It was palpable in conversations among cinematic veterans as well— the usual starter “what have you seen that you’ve really liked?” this year often became “what’s your favorite by a woman?” Was it planned that way? Director of Programming Cara Cusumano told Deadline that TFF considered “what real gender parity would look like at this festival” and “it was something that shaped the program in a meaningful way beyond just that number statistic.” And so it has:

Woman Walks Ahead; Susanna White; USA 2017; 101 min; Lead Actress: Jessica Chastain

That’s Jessica in the large photo above, walking ahead of the legendary Sioux chief Sitting Bull (Tatanka Lyotake), acted by Michael Greyeyes. She plays Caroline Weldon (1844-1921), a Brooklyn-born painter and widow— we watch her tossing his portrait into a river—and sets out by rail in 1889 for Fort Yates in the newly formed North and South Dakota territory.

The U.S. Indian Inspector and agent to the Sioux, James McLaughlin (Ciaran Hinds) is hardly welcoming, though he has a Sioux wife. “New York liberals,” he mutters. “Arrest her.” Caroline is spit upon and reviled by the Army thugs (led by a steely, cynical officer well-played by Sam Rockwell). When she finally finds her way to the Lakota reservation, the grumpy Sitting Bull is plowing potatoes in a field. He’ll sit for his portrait for $1,000, which she easily withdraws from the bank. “Your society values people by how much they have,” lectures Sitting Bull, posing uneasily because the four bullets in his body have a way of shifting around. “Ours values people by how much we give away.”

Doesn’t sound like a very promising biopic, does it? In real life Weldon was a committed expert on tribal life who wanted to live among the Sioux, and brought along a young son. Steven Knight’s adaptation of Eileen Pollack’s biography loses the kid and Weldon’s prior knowledge, leaving Jessica Chastain cast as a lone newbie who isn’t dressed for the frontier and suffers a bone-crunching beating that somehow makes her stronger. Chastain’s carted home awards for roles this tough in movies like Molly’s Game, Zero Dark Thirty, Take Shelter and A Most Violent Year.

Under the skilled direction of Susanna White, and with a breathtaking production led by Ed Zwick—who gets the same kind of top dollar-value up on screen as indie vets Christine Vachon and Lydia Dean Pilcher—Chastain crafts Woman Walks Ahead into a moving and evocative history lesson. She rides a magnificent white stallion that Sitting Bull once sashayed around Buffalo Bill’s rodeo shows.

Chastain is memorably partnered by Greyeyes, a handsome Canadian actor and member of the Plains Cree First Nation; you might remember this commanding giant of a man from Jimmy P. (2013), co-written by Kent Jones, who we’ll get to shortly. Weldon the real-life painter was Sitting Bull’s secretary and adviser; Chastain’s screen creation leans toward becoming more than that, but doesn’t. “New York ladies love a bad man,” murmurs the chief with a faint hint of mischief as he poses for her in a stream. One of Weldon’s four surviving canvasses of Sitting Bull is pictured in this review.

To its credit, Woman Walks Ahead successfully fuses a literate, intelligent screenplay into the unhappy historical realities of its time. The drama bookends Custer’s Last Stand (the slaughter of hundreds of 7th Cavalry Regiment soldiers by Sioux and Cheyenne in 1876) up to the revenge slaying of several hundred Lakota families in 1890. In its closing scenes, tribal elders vote against a government treaty that would further deepen their dependence on Washington, choosing instead to live on reduced rations and “die like the buffalo.” This leads to the assassination of Sitting Bull followed by more Lakota killings at Wounded Knee. Caroline Weldon bore witness to the tragic death of her subject. Chastain can play that, too. There are lessons here.

The History of White People in America; Clementine Briand (with Ed Bell, Jon Halperin, Pierce Freelon, Aaron Keane, Draw Takahashi); USA 2018; 9 min.

Clementine is the producer, out of Paris. Pierce is on vocals and composed with Aaron, and also wrote with Jon. Ed and Drew were the art directors/animators. Their directorial team is creating a series of 15 animated shorts which hopefully will be as blazingly original and refreshingly candid as this pilot episode, curated by Whoopi Goldberg.

The subject is racial history—how skin became color, color became race, race became power. It’s like if you spun Woman Walks Ahead back 200 years to Jamestown, where English landowners presided over a population of melded Africans and European men and women of all colors—“molasses, dark cherry-flavor, bronze, brown.”

Single and as couples who freely wed, the poor became one class that could be “bought, sold, whipped, maimed”—until Nathaniel Bacon began a populist rebellion, planting the need for togetherness among the indentured and enslaved. In 1681 the ruling class responded to Bacon’s bid for democracy, banning marriage between races. This was the beginning, the filmmakers rap out, of how white became America.

History’s images crackle with snap and outrage. There’s no pussyfooting here—the team’s line drawings, partially or fully animated, catch and reflect the fervor and tension of the lyrics. At 8 minutes and 22 seconds, a portrait of what might be Sitting Bull is shown for no more than a second.

What a movie this is going to make.

Blue Night; Fabien Constant; USA 2018; 98 min.; Lead Actress: Sarah Jessica Parker

It’s one thing to be given a fatal diagnosis of a brain tumor that’s inoperable, and that with radiation and chemotherapy you’ve got maybe—maybe—a year to live. It’s another thing to walk out of the doctor’s office into a midtown Manhattan that could care less, and try to figure out your next 24 hours. If there’s Eight Million Stories in The Naked City, this is a pretty good one.

It’s also the considerable challenge Sarah Jessica Parker has taken on in the aptly titled Blue Night, and it’s a pleasure to report she’s aced it mostly using one basic facial expression—wan edging toward desperation—that carries her through an entire day and night.

Parker plays a cabaret/club singer, Vivienne, with a touring and recording schedule that are going to go into free fall. Vivienne was once a downtown songbird with an album titled “Third and A,” where she lived and started her New York life. Today she’s a single mom nicely sequestered on 49th between Second and Third (sweeping lobby and doorman, thank you), with a high maintenance teen daughter (Gus Birney) who’s trying out her own unformed singing voice… her visiting French mom (Jacqueline Bisset, in a nice turn) who’s even higher-maintenance than the daughter…an ex-husband (Simon Baker) who’s grumpy as all get out when she turns up at his apartment as he’s trying to fashion a meal…a backup band that’s annoyed when she finally gets to a scheduled rehearsal two hours late… the band’s drummer and her current lover ( Taylor Kinney) who can’t figure out what’s eating her…and a gal pal (welcome back, Renee Zellweger) who’s celebrating a birthday out that night but appears to be totally miserable about everything in her upscale Manhattan life.

Pile in an Arabic-speaking Lyft driver with plenty of attitude who nearly blasts her out of his car with loud rock music… a bunch of private school girls who seem determined to wreck the quiet of a tiny park…a dotty lady who fixes her with a steady gaze as Vivienne stares out at the East River, and then starts regaling her with the time she saw an actual whale swimming down that river…Got it? Oh, and let’s not forget the city ambulances with their ear-splitting sirens on full that keep roaring by the distraught singer, undoubtedly hauling emergency victims who won’t make it to the city’s hospitals. We sit there wearing the same expressionless frown as the suffering Vivienne, and we feel for her.

The singer’s only friends seem to be her common-sense manager (played by a low-key Common) and the car service guy (who starts making nice at $65 an hour as he hauls her here and there through the night). She doesn’t share her diagnosis with anyone. But when she shares Rufus Wainwright’s “Unfollow the Rules” (composed for this film) with a club audience where’s she’s walked in, been recognized and asked to do just one song, it may be the most desolate vocal you’re heard since Chet Baker whispered his way through “Almost Blue” and the end of his life in Bruce Weber’s 80’s documentary.

Parker produced Blue Night, so it’s hardly surprising that “Sex In The City’s” Carrie has an intuitive feel for the city’s sharp elbows and (at times) totally uncaring ambience. Vivienne’s processing the limited time she’s got left before her Death In The City. Maybe she’s wondering how long an obit she’ll get in The New York Times, or if she’ll get one at all. If there was ever a narrative drama that earned its place in downtown’s Tribeca Film Festival, it’s this one.

Salam; Claire Fowler; USA, Wales; 14 min.; Lead Actresses: Hana Charmoun, Leslie Bibb

Salam (Hana Charmoun), also a driver for Lyft, comes home to her warm Palestinian family living in Brooklyn. We know she’s competent because everyone’s panicked by a mouse in the house, which Salam handily captures in a cup and releases in the street. Then there’s a phone call from abroad. A bombing has occurred, and the Internet and phones are down. A second call comes in and she learn her husband, Musa, a nurse, is in hospital with a serious head injury. Her family asks her to come home immediately to await further news.

Instead Salam picks up a fare—Audrey (Leslie Bibb) who’s white, blonde, cosmopolitan, snappy. Salam stops for coffee at an all-night diner and the two women talk. They’re about as different as two women can be, yet their casual conversation is friendly. On impulse, Audrey asks Salam if she’ll drive her upstate to her parents’ home. Salam agrees—we intuit this car service driver may be the major breadwinner for her family— and they start out, but Audrey takes a call and decides she must return to Brooklyn. This time when the phone rings, it’s for Salam, and it’s from abroad.

No spoilers here, but as you sense, there’s a poignant similarity in the core premises of Blue Night and Salam; both women are demonstrating their responses to terrible news. As young filmmakers worldwide learn every day, the concept is everything. Ms. Charmoun is the daughter of an American/Palestinian mother and Lebanese father. She and Ms. Bibb are cast as mirror opposites. Claire Fowler’s credits—camera, editing, production design, sound recording, music—all tuck together into a perfect jewel of a short.

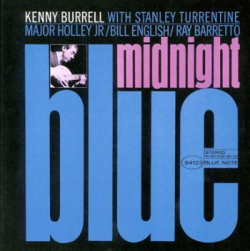

Blue Note Records: Beyond The Notes; Sophie Huber; Switzerland, USA; 85 min.

Whenever a feature documentary on a New York icon shows up at a local fest—whether it’s an on-the-town favorite like Bill Cunningham, Nora Ephron or Elaine Stritch, or a bad apple like Anthony Weiner—every true Manhattanite movie lover’s antenna goes up. You’d better get this one right, we mutter. And when the subject is a beloved New York City institution like Blue Note records, whose seminal jazz recordings date back to 1939, the stakes are really high. If if ain’t right, both press and public will unite as judge, jury and executioner.

The gratifying news is that Huber’s Blue Note Records: Beyond The Notes works like gangbusters. The Swiss-born, middle-age documentarian started with two fundamental concepts that she’s stayed true to through three-plus years of search and prep: she’s chosen to let Blue Note’s musicians and producers be the exclusive storytellers and historians, and she’s given primary emphasis to the early years when you could spot a Blue Note album in any record shop just by Frank Wolff’s stark photos and Reid Miles’ snazzy graphics. These are crucial aesthetic decisions that let Huber honor the all-important early work that still graces the windows of music stores like the Academy on West 18th.

Her thumbnail captures of the work of seminal pioneers like Thelonious Monk, Clifford Brown, Art Blakey, Miles Davis, Bud Powell and John Coltrane are remarkable for their fullness. This is a director whose knowledge of the jazz world was formed through a few Blue Note albums owned by her dad, plus trips to jazz fests in Bern. Yet her Blue Note sampler from over a thousand albums—half of which got recorded in Rudy Van Gelder’s Englewood studio starting in 1959—is amazingly comprehensive. For an 84-minute doc, about the length of a double-LP compilation album, Huber gets gold stars.

She and editor Russell Greene fasten on Wolff’s gigantic photo collection (lovingly maintained by producer/historian Michael Cuscuna) juxtaposed with Miles’ cover photos. There are select archival clips but the music plays largely against the stills. “Those guys looked so cool,” marvels Don Wax, the label’s ever-present producer and now president, still sporting his signature slouch hat and dark glasses. “I’d see these guys in the room with all the smoke it looked like it was always dark, there were no walls you could see. And I just wanted to be there. The Beatles looked cool, Hendrix looked cool, these guys looked cooler.”

Contemporary masters like Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock testify to the “messed-up situations” and a constant search for self that often came through “fighting with your instrument” to create new music. There was deep community among the musicians of the 50s and 60s, in part because their efforts were fully supported and championed by co-founders Wolffe and Alfred Lions— Jews from Berlin who started a label not to make money but to make music. They paid for rehearsal space and hung with the musicians, sharing meals and constantly urging them to innovate, to avoid “covering” other artists’ music.

The heart of Blue Note’s catalog is the be bop, hard bop, and post-bop eras. We get a few glimpses of the hot jazz and swing eras of the 40s, and a few more examples of the soul jazz, avant-garde and fusion bands of the 70s that migrated into today’s hip hop. But thankfully Huber has stayed a purist honoring purists. She gives considerable screen time to alto maestro Lou Donaldson, who joined the label in 1952 and still fronts his own band at 92. Donaldson is a wry, cagey cat whose big hit, “Alligator Bogaloo,” exemplifies his crafty wit. He’s seen it all and you can’t get enough of him.

It was perhaps inevitable that hit recordings would emerge on the Blue Note label. Trumpet ace Lee Morgan’s “The Sidewinder” and pianist Horace Silver’s “Song for My Father” made distributors clamor for more product and, ironically, led to slow payments for profitable releases. Neither Wolfe nor Lion wanted a traditional company filled with meetings and the churn of corporate existence, and left the label. Blue Note was bought and briefly owned by Liberty Records, languishing and ceasing production in the 70s. EMI-Capital installed Bruce Landvall, a top Columbia producer, as its head in 1984. He enticed major musicians like Jackie McLean and Freddie Hubbard back to the label, as well as signing and guiding Norah Jones to phenomenal success (her first album sold 11 million copies), and opening the door to other female jazz artists. When Lundvall passed in 2012, Don Was was entrusted to run operations. Huber is careful to position Robert Glasper, Ambrose Akinmusire and Kendrick Scott (recent label additions), along with Hancock and Shorter (’62 and ’64 alums) as part of the glue that binds different generations and jazz styles. Wayne Shorter talks about “creating value” for future generations, and he’s not talking about money. Blue Note was and still is all about creating art that endures, that has lasting cultural and artistic value. That’s the “beyond the notes” in Huber’s title.

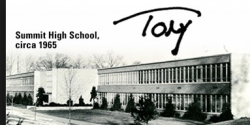

The Velvet Underground Played At My High School; Tony Jannelli, Robert Pietri; USA 2018; 8 min.

Jannelli was one of a handful of what he calls “eyewitnesses and survivors” of The Velvet Underground’s initial set at his Summit, New Jersey high school in the winter of ’65. Tony’s own band, The Noblemen, hadn’t been having much success, and he and his classmates went one night to hear a local group, The Myddle Class, which was getting airplay with a 45rpm single on Atco of Carole King and Gerry Goffin’s “Free As The Wind.”

Pietri and his crew of digital inkers are illustrating all this with grungy, inky-black strokes and slashes. It’s guerrilla animation. Before the headlining Myddle Class came on, in wandered Lou, John, Maureen and Sterling and cranked up “Venus in Furs.” “They were scratchy and out-of-tune, with an electric violin droning and a drummer who played standing up,” recalls Tony. “They sounded like someone killing a cat. We thought: ‘Who are these people? Are they playing a joke on us?’”

The animation is twitching away. We’re watching smeared, rotoscoped footage of Reed, Cale, Tucker and Morrison grinding along. The teen walkouts start building. Then the band segues into a signature anthem, “Heroin.” Jannelli and his classmates can’t believe their eyes and ears: “We were told in health class, ‘don’t smoke marijuana, it will lead to heroin,’” he groans, “and here’s a band actually singing about it.” The negative responses grew: “A roar of disbelief swelled to a mighty howl of outrage and bewilderment.” Jannelli confides how a handful of admirers, himself included, hunkered down at the back, finding the experience “dangerously cool.” It was their first exposure to “underground art…and it came to us, we didn’t even have to ask for it.”

This is one irresistible arty and dangerously cool short. Peitri’s wonderfully splotched and blotched imagery reveals a different coming-of-age experience for kids who never found their way back to the jazz bins in retail outlets like Sam Goody’s and Tower Records, but huddled around stacks of 45 singles that were closer to the listening booths.

The Sci-Fi Corner

UI—Soon We Will All Be One; Johannes Mucke & Patrick Sturm; Austria 2018; 14 min. Actress: Tanja Petrovsky

Here’s the setup for a striking short that feels, slightly, like it’s standing on the shoulders of 2001: A Space Odyssey: Space pilot Kira (Tanja Petrosky) is zipping her snow glider through the icy wastes of Antarctica (the Austrian alps in Vorarlberg standing in beautifully). She’s searching for a tiny antenna that’s sending out a distorted signal in her territory, and she’s being guided by a calm, velvety contact voice, Alan (Dennis Kozeluh), who may nudge you right away into thinking about your old movie buddy HAL, Stanley Kubrick’s maverick killer computer.

Kira finds the little lost switch in the snow. It looks innocent enough and she can’t account for its signal interference. But she also finds herself facing a free-standing monolithic structure in this blindingly white void. Gingerly, she pushes her way inside this imposing structure—and finds herself standing on and surrounded by 26,000 small steel switches, attached to 104 perforated steel sheets, all facing a tall black slab. Oh, oh—now our rusty memory does an instant 360 to Kubrick’s slab in 2001A Space Odyssey. The door Kira stepped through slams shut, she’s thrown to the floor, and this strong, supple, Ripley-like woman is about to be absorbed into some super artificial intelligence.

The film’s title tips us to its ultimate warning—“UI” is you-and-I, and, yes, soon we will all be one. Alan’s purring question ices it: “Kira,” he asks innocently as she gasps her last breaths, “did you find what you’ve been looking for?” And in case there’s any doubt, Cilla Black’s soaring lyrics to “You’re My World” (“If our love ceases to be, then it’s the end of my world for me”) leave no doubt Kira’s glided into an AI world she can’t escape. Co-director Mucke, who also functions as the conceptual artist and matte painter, has concocted a lulu of a fantasy that would have pleased Arthur C. Clarke, and, for that matter, Philip K. Dick. Ms. Petrosky, like Sigourney Weaver’s space warrior, looks capable of dispatching any creepy alien. But a 26,000 switch superpower must be something like a jumbotron in Times Square with 24 million LED pixels, that gives way and falls on your head. No way you’re surviving that one.

Laboratory Conditions; Jocelyn Stamat; USA, 2018; 16 min; Lead Actresses: Marisa Tomei, Minnie Driver

One reason book lovers say Manhattan no longer supports a science-fiction or fantasy bookstore is that real life has become so unbelievable and, well, utterly fantastic. After all, 90 million Facebook users recently had their psychographic data harvested by alleged academics, who sold it to bad actors who created advertising messages that probably influenced a presidential election.

Given that reality, it shouldn’t surprise us that Minnie Driver is playing Marjorie, the chair of a university research department, who’s locked an old, dying alcoholic without family into a sealed “vault of protection” where her inquiring team can watch him expire and hopefully harvest his soul. You understand Minnie’s doing this for, as they say, research-purposes-only.

It’s hardly a new cinematic concept, if you recall Flatliners. A closer parallel here would be the transmogrification of the soul as visualized in Gus Van Sant’s Last Days (2005). Van Sant’s narrative drama of a rock star’s despair and suicide showed the young man’s soul slipping out of his corpse like a lightly ghosted second skin and drifting heavenward, presumably toward a gentler existence or at least a higher one. This is essentially what happens in Stamat’s edgy, eerie treatise, except the angry soul of the deceased is trapped inside that atomically sealed room and barges around looking mad as hell. In an artistic conceit that only a science fiction narrative drama could pull off, Dr. Holloway (Marisa Tomei), the emergency room physician who’s been vigorously protesting the theft of her patient, is the lone person who can see this apparition that’s literally bouncing off the walls and trying to claw through the ceiling.

Director Stamat, M.D. is a Harvard-trained otolaryngologist, so the screenplay by Terry Rossio bristles with authentic medical jargon. What makes Dr. Stamat’s film deliciously watchable isn’t its goofy plot but the furious debates between the authoritative Marjorie and the distressed Dr. Holloway. It’s Driver vs. Tomei, both highly assured pros. Marjorie the researcher argues for learning more about the continuity of spiritual existence after death—in effect, giving death new meaning. Emma the physician regards Marjorie as a predator, a female Dr. Frankenstein. But it’s Emma who witnesses what happens when her patient (played by a remarkably resilient and elastic John Kearney) expires. Shocks galore ensue—this is a short poised and primed to become a feature-length horror movie.

The Seagull; Michael Mayer; USA 2018; 98 min.; Lead Actresses: Annette Bening, Saoirse Ronan, Elisabeth Moss

If you found 20th Century Women pleasantly female-centric —watching Annette Bening playing a single, exasperated Santa Barbara mom who enlists two young women (acted by Greta Gerwig and Elle Fanning) to shape up her teenage son—treat yourself to an encore evening with Bening and two more of-the-moment actresses whose work you’ve come to anticipate. The Seagull is the newest, lushly aromatic treatment of Anton Chekhov’s 1896 play.

A distributor less principled than Sony Pictures Classics might have been tempted to put Chekhov’s Seagull title in tiny parenthesis and retitle this movie 19th Century Women, thus linking the ever-versatile Bening to both films. She’s even better here, costumed to the teeth as a prissy stage actress who holds court and flounces around her brother’s lakeside estate in a sylvan Russian forest. ( But then 19th Century Women probably wouldn’t get your heart racing much faster than 20th Century Women, or, for that matter, 21st Century Fox.)

Modern translations of Chekhov’s ruminations on long, long ago theater art and its artists depend on big-name casts. Sydney Lumet’s 60s movie starred Vanessa Redgrave and Simone Signoret with James Mason. A Broadway production in the 90s fronted Tyne Daly and Laura Linney opposite Ethan Hawke and Jon Voight. Joe Papp’s Public Theater staging boasted Meryl Streep, Marcia Gay Hayden and Natalie Portman, along with Christopher Walken and Philip Seymour Hoffman. Yet another Broadway revival starred Kristin Scott Thomas, Carey Mulligan and Zoe Kazan playing off Peter Sarsgaard. The key appeal in drawing contemporary audiences into The Seagull is an ensemble cast peppered with names you know. That’s what Mayer and Sony are betting on this time around.

All three female leads here are exemplary; this was one of Tribeca’s sharpest narrative dramas. The film, like the play, is a round-robin of misalliances. Sorin, the estate’s owner, is played by a subdued Brian Dennehy, who for once doesn’t have to work at hurricane strength. He’s keeping a wary eye on his sister Irina (Bening) and her young writer/ lover, Boris Trigorin (Corey Stoll). Meanwhile, Irina’s son Konstantin (Billy Howie) is trying to escape the clutches of Masha (Moss), the boozy, lonely daughter of the estate manager. Konstantin is head-over-heels in love with Nina (Ronan), a local girl who’s enamored with acting as much as the achingly handsome Boris. So the Chekhov wheel turns.

Stephen Karam’s adaptation lets Mayer’s select cast bring brio and zest to the playwright’s fusty machinery. The picture has a sumptuously lazy look and a cast whose most experienced veterans, Bening and Dennehy, graciously surrender a lot of screen time to Ronan, Stoll and Moss. Ms. Bening in particular is as regal and imperious as Bette Davis was playing the English monarch Elizabeth I in Fox’s The Virgin Queen 63 years go. Yet Bening seems to sense, like Davis, that she can command a movie with more assurance in this kind of role than in her recent portrayal of noir siren Gloria Grahame in Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool, another Sony Pictures Classics release that vanished off screens in a New York minute.

Watch Bening, and Ronan, and Moss rework what we know today as modern drama. TFF is, as always, a something-for-everyone film festival, and The Seagull is its mandatory art class.

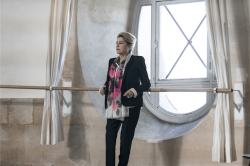

Rise Of A Star; James Bort; France, 2018; 19 min.; Lead Actresses: Dorothee Gilbert, Catherine Deneuve

Never underestimate star power. If your premise is seeking a credibility that the material almost certainly denies, the right actress can give you that. Stars wield magic. Case in point: Dorothee Gilbert, the exquisite danseuse etoile of L’Opera National de Paris, is cast as Emma, the principal dancer in Ravel’s “Bolero” which is about to start a three-week run at the Bolshoi. Emma is stressed and when she looks at herself in the mirror in her dressing room, and gently presses her stomach, and quietly smiles, we know instantly that she’s pregnant.

Three months pregnant. One by one, the company becomes privy to Emma’s secret. Will she drop out? Her fellow dancers certainly think she should. Her potential replacement is even more emphatic, accusing her of potentially harming her baby. The Ballet Master (Pierre Deladonchamps) is furious with Emma’s seeming inability to face reality. Then the Director, Mlle. Jean, walks in to view the final dress, and who do you suppose is playing her? How about Catherine Deneuve. The enchanting Miss Gilbert has owned the screen up until that moment, but the one we’re immediately drawn to is a movie legend, and legends don’t often appear in shorts. (The last two—Sophia Loren in Human Voice (2014) and Charlotte Rampling in The End (2012)—were over-the-moon critic’s choices.)

It’s the Director’s call. You’ll accept her decision, because she’s got the easy, quiet, empathetic authority that screen legends have earned over a lifetime in the dark with you. At 74, the camera still loves Deneuve, as do we.

Diane; Kent Jones; USA 2018; 95 min.; Lead Actresses: Mary Kay Place, Estelle Parsons, Joyce Van Patten, Deirdre O’Connell, Glynnis O’Connor, Phyllis Somerville

Raymond Carver, who authored many of the 20th century’s most penetrating short stories on working class people trapped in alcoholism and addiction, had an intense dislike of being called “a minimalist.” He told this viewer one evening outside the Symphony Space theater where he was giving a reading that he could tolerate being described as a “dirty realist.”

Many of Carver’s stories are tales of everyday small town folks who simply can’t get traction in their lives. They’re stuck driving to and from numbing jobs on back country roads, and they drink their nights away in rural taverns and kitchens. (You would recall the setting of the Oscar-winning Birdman was two married couples sitting around a shabby kitchen table getting loaded as they rehearse a Broadway stage adaptation of Carver’s grim tale, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.” )

Given the screen content and frank interview comments by Kent Jones on Diane, his first dramatic feature as writer/director, you can add Jones to the dirty realist list. His film is an impassioned, fully realized give-and-take of the archetypal eternal struggle by an older single mom, Diane (Mary Kay Place), repeatedly trying and failing, over and over, to get her grown train wreck of a son, Brian (Jake Lacy) sober or back into rehab or somehow away from the hard-drug blackouts he’s slowly succumbing to. Diane stubbornly refuses to throw this tin can kid out (Lacy is 33 and looks it), and keeps half-believing the stoic denials, pleading rationalizations, out-of-control rages and desperate pleadings he keeps winging at her whenever he’s not passed out. It’s a deep, painful etching of the classic enabler and co-dependent.

For a while, all your sympathy and surely much of your heart go out to the holier-than-thou portrait of the suffering mother that Place and writer/director Jones are brilliantly engineering. Diane dutifully sits at the bedside of cousin Donna (Deirdre O’Connell) who’s dying of cervical cancer. She volunteers in a church soup kitchen, cheerfully feeding the homeless. She’s a pal and companion to Donna’s mom (Estelle Parsons) , to a fellow kitchen volunteer (Andrea Martin), to a raft of good village friends and family (Glynnis O’Connor, Phyllis Somerville ) in this totally nondescript town. (Upstate New York doubling for western Massachusetts.). She can’t do enough for the people around her because she can’t do anything for her son. We watch Diane tirelessly making her weary rounds and driving those lonesome roads, day after day, night after night, and we sigh, what a saint.

It’s too good to be truth, and you may get an itchy feeling Jones is setting you up for something. After all, this is the director of The New York Film Festival wearing his writer/director hat, stretching his artistic muscles way beyond his screenwriting on Jimmy P and his masterful assembly of the Hitchcock/Truffaut documentary. He’s got Marty Scorsese onboard as an executive producer, which should tell you right away we may not be observing a Florence Nightingale. And we’re not.

The first hint Jones drops is when Diane mentions she once was a big fan of Chick Corea, the jazz fusion pianist. Oh, really? The second hint—and this hurts like a bear trap clamping onto your leg—is when Diane goes to the local saloon, throws some coins in the jukebox, and starts bobbing and weaving to Leon Russell belting out arcane rockers as she gets plastered to the gills, to the point where the bar owners cut her off and haul her home. The misery index in Diane is beginning to tilt in crazy directions, as it does in virtually every Raymond Carver story. Things are not as they seem. (That was Jim Thompson’s credo, too, and Scorsese produced Thompson’s The Grifters, as well.)

Jones has a number of other storytelling twists up his sleeve, which you’ll need to discover on your own. One is the kind of disappointment in Carver stories that we’ve come to accept. Another is a whopper of a plot twist in the closing minutes that you won’t see coming and that makes you rethink Jones’ entire movie. The director has provided some helpful insights to his conceptual thinking: Asked whether Diane is an amalgamation of different people, Jones has answered, “Yes, but basically, she’s my mother.” Asked about its setting, Jones says “we shot it in Kingston, Saugerties and Palenville—more or less the same kind of landscape, and the same feeling, same kind of world, same kinds of building and people and distances between spaces as I grew up in the Berkshires.”

Jones is familiar with 12-step recovery programs, and mentions Step 9 of making amends. He then poses the essence of Step 3: “Where does spirituality, which I take to mean awareness of the unknown and the unseen, happen in the life of this woman?” And then he’s asked about the film’s final passages, “as the film transitions to a different plane,”and responds by saying: “But that’s life…the porous borders between imagination and reality, now and then, space and time. Life sort of is a hallucination. I’m reminded of this beautiful thing that David Hockney said to Martin Gayford in their book of interviews, that he’s all for people going into outer space, but that the space between earth and Jupiter is finally much less mysterious and interesting than the space between you and me.”

It’s that elusive, ineffable space between mother and son that Jones is digging into here. Suffice it to note it’s on a much higher plane of dirty realism.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the New York Film Festival, Sept. 28-Oct. 14, at The Film Society of Lincoln Center.

Regions: New York, New York City