New York Film Festival 2013 – Critic’s Choice

Last year’s 50th New York Film Festival (NYFF) gave a 21-gun salute sendoff to its departing director, Richard Pena. It far exceeded the breadth, width, and depth of a half-century of festivals. This year’s extravaganza, headed by Kent Jones, Film Comment’s scholar/essayist and now screenwriter (Jimmy P: Psychotherapy of a Plains Indian), goes even broader, wider, and deeper in the varieties of films being shown. Consider this groaning board of choices:

Forty four main slate features, 25 of which are receiving their US or North American premieres. Eight “cinematic portraits.” Twelve revivals. Six retrospectives. Twelve immigration reform films. Twenty shorts. Thirty-four “views from the Avant-Garde.” Fifteen immersive/interactive “convergence”presentations. Three “applied science” selections. Five director dialogues. Ten free screenings. Plus—and here’s the glamorous kicker—gala tributes to Cate Blanchett and Ralph Fiennes. Are your eyes glazing over?

By mid-afternoon September 24th, three days before the festival’s first red carpet (Tom Hanks in Captain Phillips), 56 features were sold out and forming standby lists, with curators scrambling to add extra showings. It’s a stunning demonstration of the vaunted New York principle that nothing succeeds like excess.

The concept of separate silos for themed offerings can be credited locally to the annual Tribeca Film Festival, which from its initial launch in 2002 began evolving a heady mix that embraced opening nights with big studio fare; a substantial amount of documentary and narrative content unblessed by other film festivals; an unmatched dedication to shorts; and a widening array of convergence events defined by installations and other non-traditional forms of exhibition. The Film Society of Lincoln Center has taken its time deciding whether to play serious catch-up, and this year its curators have elected to match and perhaps even exceed Tribeca’s all-encompassing strategies and menus. NYFF doesn’t have a free “drive-in” like Tribeca, but then Lincoln Center doesn’t have a pier on the water. (The neighboring Metropolitan Opera has a gigantic outdoor screen and projection system facing the center’s iconic fountain.)

What’s all this mean for viewers? Well, prices have climbed. Movies at the sleekly renovated Alice Tully Hall run $20-25. Films in venues including the exceedingly comfortable Walter Reade Theater and the tasty new Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center are $15-20. Opening and closing nights, centerpiece and gala tributes range from $50 to $100. Other programs run $10-15. A variety of all-access and discount packages are available. There’s even a virtual waiting room (with countdown clock) for ticket purchases. The entire two weeks of attractions are compressed into a handy, handsome 20-page 4-color brochure.

Let’s go to the movies. Critic’s choices below are in the order seen in pre-screenings.

Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq

(Nancy Buirski. 2013. USA. 87 min.)

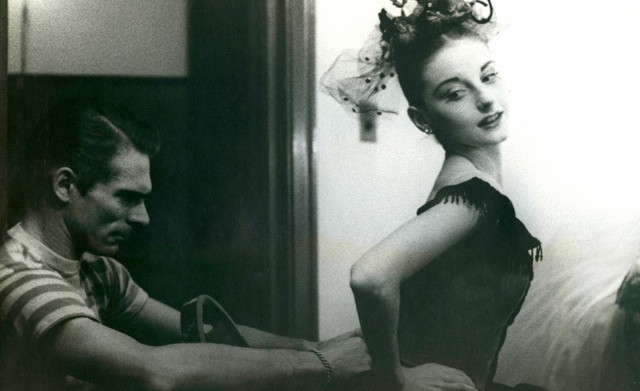

Never, ever forget that a fest’s most memorable moments can arrive like sublime gifts from its most modest images. The opening and closing scenes of Nancy Buirski’s luminous documentary, Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq of the ballerina Tanny Le Clercq are from a faded black-and-white kinescope in which the eternally youthful Le Clercq is rehearsing in a bare, mirrored studio. In the kine she’s partnered by a very young Jacques D’Amboise, who is bare-chested. (The photo above of Tanny is not from the kine.)

In the video, Le Clercq and D’Amboise are rehearsing Debussy’s Afternoon of a Faun, created for her by the famed Jerome Robbins. They’re playing to their mirrored images; the mirrors are a third character in what you might call a pas de trois. D’Amboise is simulating some kind of hulking brute of an animal, perhaps a bear. Le Clercq stretches her impossibly long legs and preens like a witty, stylish colt who hasn’t yet turned into a thoroughbred. She will remind you instantly of Audrey Hepburn, and like Hepburn she already knows the art of enchantment. She seems to personify what Frank O’Hara described as “perfection’s broken heart”: Because you’re beautiful you’re hunted, and with the courage of a vase you refine to become a deer or a tree…and the world holds its breath to see if you’re free, and safe. At the end of the piece, which forms the closure of Buirski’s doc, D’Amboise gives Le Clercq a delicate, tentative kiss on the cheek, and the gesture is transcendent.

Born in Paris in 1929, Le Clercq was discovered by George Balanchine at the age of 14 and became the first New York City Ballet ballerina personally trained by the mercurial “Mr. B.” She created 32 roles over a 10-year career, secure as Balanchine’s muse even as she became his fourth wife, and equally confident with Robbins, who had also fallen in love with her. The film makes clear that the sexual dynamic of these ballet masters “feeling the heft, weight and sweat of Tanny” are what inspired her to “seek the unobtainable” in her work.

What stopped her career was her refusal, before traveling to Copenhagen with the New York City Ballet in 1956, to be inoculated with the Salk vaccine as a preventive measure against contracting polio, at that time a widespread and deadly disease. Le Clercq was stricken with paralytic polio, placed in an iron lung, and never danced or walked again. While her two professional allies both tried to nurture her recovery, Balanchine divorced her in 1969 to pursue Suzanne Farrell, and Robbins moved on with his career.

Writer/producer/director Buirski, along with co-producer and veteran documentarian Ric Burns (and Martin Scorsese who served as project advisor) deftly organizes Le Clercq’s story, including her later years teaching at Arthur Mitchell’s Dance Theatre of Harlem, where she used her hands to block and choreograph. Mitchell, D’Amboise, and Barbara Horgan (who became Balanchine’s personal assistant in 1962 and today chairs the board of Balanchine’s foundation) are the key on-camera narrators. Le Clercq ages grandly, her long white hair falling to her waist, passing away at age 71 in 2000, and outliving Balanchine by 17 years.

Afternoon of a Faun takes its position as this NYFF’s sweet spot.

Afternoon of a Faun screens September 30th at 6 pm; October 11th at 1 pm; and October 13th at 6 pm.

The Square

(Jehane Noujaim. 2013. USA/Egypt. 104 min.)

“We’re not looking for a leader, we’re looking for a conscience,” states Ahmed Hassan, the spirited young revolutionary who holds the screen, and often our hearts, in Jehane Noujaim’s riveting doc, The Square, which covers the past two years of turmoil in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. Hassan isn’t apolitical, but he has no taste either for his nation’s deposed strongman, Hosni Mubarek, or for the Muslim Brotherhood’s narrowly elected president, Mohammed Morsi. Hassan’s fearless bravado is cracked only by the killer army troops called in to brutally repress the Arab Spring uprising, leaving him bloody but unbowed.

What a shrewd directorial concept. You can start thinking of Noujaim, a tall, articulate and beautifully imposing Egyptian-American filmmaker, as the Mideast Kathryn Bigelow. Her cameras wade into the thick of rioting and chaos, holding compositions and capturing the sudden terror of battle with calm surety and remarkable color clarity. There are few shaky images and the street clashes are underscored by a humming, ominous instrumental music track. Clearly influenced by D.A. Pennebaker’s advice that she seize and hold onto one character that audiences will identify with and respect, Noujaim has chosen in Hassan the ideal subject. He’s a likeable, clear-eyed young man, totally without guile; in a contemporary history college course he’d be the brightest kid in the room. Hassan becomes The Square’s moral conscience as well as our student guide through two unimaginable years in a nation’s search for “bread, freedom, social justice and dignity.”

Noujaim has surrounded Hassan with a select supporting cast that brings added empathy and understanding to the shifting political winds: Ramy Essam is the acknowledged singer/songwriter of the revolution, and Khalid Abdalla is a known film star (The Kite Runner, United 93); both are congenial and savvy, and each lends an air of professional endorsement to the massive rallies. Aida El Kashaef, a filmmaker in her 20s, and Ragia Omran, a human rights lawyer, contribute solidarity and a welcome female presence to the arduous events we witness.

And finally, most importantly, Magdy Ashour is Hassan’s intellectual opposite—a middle-age father of four and Muslim Brotherhood security figure who slowly, reluctantly, comes to abhor the constant violence that threatens his family and eventually embraces Hassan’s political neutrality. This was a painful decision. As producer Karim Amer has pointed out, soldiering in Egypt has a long tradition in countless families, and men are acutely aware that military duty is one of Egypt’s few meritocracies. By the time Noujaim stopped filming this past summer, Ashour and Hassan were united in finding a middle road toward a peaceful Egypt. Together they’re looking for a conscience for their country, and The Square should carry their search to the world.

The Square screens October 3rd at 8:30 pm.

Inside Llewyn Davis

(Joel and Ethan Coen. 2013. USA. 105 min.)

Deep into this disquieting tale of a struggling folk singer in New York’s 1962 club scene, Davis (Oscar Isaac) heads out to Chicago with his guitar. Though he doesn’t own a winter coat and his Thom McAn shoes are leaking snow, Davis is obsessed with wheedling an interview with the manager of the Gate of Horn, a Midwest showplace for emerging folk artists like Odetta and Bob Gibson.

The manager, a world-weary seen-it-all F. Murray Abraham (playing the legendary Bud Grossman) shuffles into the empty club and tells the nervous kid to sit down and sing. Davis chooses a traditional English ballad, The Death of Queen Jane and gives it his all. The club owner fixes Davis with a stony stare and says quietly, “I don’t see a lot of money here.”

Grossman’s assessment confirms our worst suspicions, that this 60s slacker is a conventional tenor who covers Irish/Celtic tunes and has little stage presence besides that sullen New York attitude. The moment nails Inside Llewyn Davis’s most compelling strengths—the unremarkable talent of its title character, and the Coen brothers’ stubborn fascination with life’s losers.

Their screenplay repeatedly stacks the deck against Davis. His sister has kicked him out of her home in Queens; he’s broke and living night-to-night on borrowed sofas; he’s slept with a singing partner’s wife (Carey Mulligan) and gotten her pregnant; the abortionist he’s taking her to tells Davis he has a two-year-old love child he’s never seen from another woman he impregnated who decided to have the baby; neither of his albums has attracted critical attention or sold at retail; he gets drunk and heckles a nervous female singer during her act, receiving a savage beating from her husband who corners him in an alley outside the club (styled after the Gaslight and Gerdes Folk City); and he can’t even re-enlist in the Merchant Marine (like his dad, who’s in a drab nursing home) because he owes union dues and didn’t keep necessary duty cards. On top of all this, he leaves a window open in a family’s apartment he’s crashing in and their cat escapes.

Davis’s pursuit and care of that cat—the extraordinarily appealing orange tabby, Ulysses—is given a lot of screen time and is the singer’s one redeeming quality. As a dramatic device the cat works the way Kevin Spacey’s love for his dying dog in Margin Call helped soften Spacey’s cold Wall Street persona. Even when Davis, who lives a sour life of “authenticity” both obstinately and selfishly, concludes a set in a Greenwich Village club to a modest but appreciative audience, we note the singer following him sure looks and sounds like—well, you’ll discover that ironic note yourself. Should we really care about Davis, a testy remnant of the 50s folk/beat scene who’s going nowhere fast?

Oddly, we do. The Coens have become master storytellers and champions of eccentrics and the marginalized, and the craft they infuse in their cinematography, production design, music, and costuming is as good as anything on the American screen today. Oscar Isaac is their inspired choice for the lead; while he’s no better a vocal interpreter than Dave Van Ronk (the 60s Village songsmith whose life and times have found their way in part into Davis’ story), Isaac exudes a low-key, charismatic presence as a shadow figure in NYC’s early folk scene. He plays well against a refreshingly snappish Carey Mulligan…on the same bill as a spanking clean Justin Timberlake (playing a folk type Davis never wants to become)…and riding to Chicago with John Goodman, who morphs his recent drug chemist in Flight into an amusing jazz musician mashup of Doc Pomus and Dr. John.

At a fest Q&A, the Coen brothers talked about how they weighed shooting Inside Llewyn Davis in 16mm black-and-white, but opted for a muted and grayed over (and splendidly propped) Manhattan shot in 35mm color. The Coens again flesh out scenes with supporting character grotesques not unlike the odd ducks in early David Lynch pictures. Their editing is clipped and tight. T-Bone Burnett’s score wisely uses songs that Van Ronk himself once recorded. The picture closes with the scenes it opened with, making us realize we’ve watched a whole week in Davis’s life spin by in little more than an hour and a half. Make no mistake, it’s absorbing viewing and easy listening on what Ralph Ellison, the author of Invisible Man, called “the lower frequencies.”

The second showing of Inside Llewyn Davis will be October 5th at 3:15 pm.

Captain Phillips

(Paul Greengrass. 2013. USA. 134 min.)

Terrorism now comes in all sizes and shapes. Four years ago a 17,000 ton Danish cargo ship owned by the Maersk Corp. was seized by four young armed pirates 200 miles off the coast of Eyl, Somalia. When the merchant mariner captain, Richard Phillips, hid most of his small crew in the engine room, the Somalis decided to kidnap Phillips for ransom, holding him in an enclosed metal lifeboat headed for their coast. The US Navy immediately mounted an extensive night-and-day rescue operation to try and save the captain.

Director Paul Greengrass has said he wanted this film “to look at a broader conflict in our world—the conflict between the haves and have-nots.” But Tobias Lindholm’s A Hijacking premiered at the New Directors/New Films fest in March as a critic’s choice and already covered that base. A Hijacking focused at length on the dollars-and-cents dynamic between the corporate boardroom owner of a cargo ship taken over by Somalis in the Indian Ocean, and the frenzied outlaws who wanted millions in exchange for the lives of the crew. The buttoned-up ship owner exec spent that film whittling down the price demanded by a ragged band of thugs—a vivid case study of how the one percent clings to its wealth and protects the interest of its stakeholders.

Greengrass is having none of that. As you’d expect from the director of United 93, Bloody Sunday and two of the Matt Damon Bourne thrillers, Captain Phillips is built around a far more visceral and nail-biting question: Will American sea power, Navy SEAL training and state-of-the-art weaponry save Tom Hanks from being lynched at sea?

The pirates are played by four newcomers, all with Somali or Kenyan roots and ancestries, who were recruited from the Somali community in Minneapolis. The leader, named Muse, is the 28-year-old Barkhad Abdi. He starts bold and confident, telling Hanks to “relax, Captain, relax…just business…no Al Qaeda…just stop the ship.” But as their plot falls apart after they take the captain into the lifeboat and spot an American destroyer, frigate, assault ship and helicopters in hot pursuit, Muse and his gang’s calculations turn to desperation—much like their counterparts in Lindholm’s movie A Hijacking.

Hanks, at 57 playing a “trucker of the sea,”and the oldest film star to have survived Greengrass’s Cinema of Exhaustion, is equal to the demands of his role, which are considerable. Greengrass has no equal at pushing over-the-top suspense levels into dimensions of hysteria that truly terrify. He did that to a plane-full of people in United 93, and here he’s pushing one of America’s most beloved box office champs into wrenching agonies Hanks hasn’t had to create since his Oscar-winning turn as the AIDS-stricken lawyer in Philadelphia. But the actor takes a lickin’ and keeps on tickin’; his final moments in the picture are stunning examples of how actors find truth in art as well as in their own fatigue. These scenes are as moving as Denzel Washington’s collapse on the witness stand in Flight.

That latter film, by the way, closed last year’s New York Film Festival, just as Captain Phillips opened this year’s. You may be seeing a new style of cinema mainstreaming in the industry’s most closely watched film festival.

Captain Phillips had its world premiere September 27th and will open nationally on October 11th.

Aujourd’hui

(Nicolas Saada. 2012. France. 8 min.)

Casting choices you’d never imagine in your wildest dreams dot this festival.

Among feature-length films, consider The Immigrant. James Gray, a most voluble and forthcoming director, says he chose Marion Cotillard to act the title role after a first-time meeting in a French restaurant “during which she threw a piece of bread at me.” Gray wasn’t familiar with her work and had no idea how she’d play as a desperately shy Polish Catholic immigrant arriving at Ellis Island in 1921. He also wasn’t sure how she’d work against his customary leading man, Joaquin Phoenix, here cast as a shady entrepreneur who leads her into prostitution. “There was something almost radiant about her face,” Gray recalls, and it’s true—Cotillard infuses the movie with an angelic, orphaned melancholy.

Arnaud Desplechin is even more direct, detailing the enormous disparity between his two leading actors in Jimmy P: Psychotherapy of a Plains Indian. A meticulous cross-examination of anthropology and psychoanalysis following World War II, his film details the hospitalization of a Native American Blackfoot traumatized by war combat, and his treatment in a Kansas hospital by a French psychoanalyst specializing in Native American culture. “I chose Mathieu Almaric as the psychoanalyst, and wanted someone completely opposite to play the American GI, and that was Benicio del Toro,” says Desplechin. The friendship that evolves between doctor and patient is as surprising as it is poignant, forcing us to see both del Toro and Almaric in remarkable new ways.

Neither of these two heavyweight dramas with their decidedly offbeat casting can adequately prepare you for the surprise of Nicholas Saada’s eight-minute short Aujourd’hui, co-produced by Elisha Karmitz, son of the veteran producer Martin Karmitz.

A well-dressed, confident French mother (Bérenice Béjo, the glamorous young ingénue of the Oscar winner, The Artist) drops her middle-school son at the front door of an urban Paris school. She continues toward her office in the busy morning rush hour, glimpsing overhead statuary of ancient Roman gods. Across an intersection, she spots a bedraggled older man urgently reaching out and attempting to grab the arms of a passersby.

As she nears him, we nearly drop our popcorn. Omigod, it’s Frederick Wiseman, the legendary documentarian who’s showing his four-hour At Berkeley in the fest. With his wizened face and drawn eyes, he looks like the soothsayer in Julius Caesar who warned Caesar of The Ides of March. He also bears a resemblance to some Roman god we’ve spotted on a building. Wiseman gets a hand on Béjo and whispers something to her. She pulls away.

Arriving at her ultra-modern office building, she takes the elevator to her floor, which appears to house a university library. She pauses to examine a postcard, which shows a bright orange landscape with comets streaking through the sky. This may trigger in your mind another, longer line from Julius Caesar in which Caesar’s wife, Calpurnia, tells him, “When beggars die there are no comets seen, the hours themselves blaze forth the death of princes.”

Suddenly sirens start wailing out in the streets. Béjo glances up and notices comet trails streaking across the sky. We cut to her son—where? In the schoolyard—looking up. The skies suddenly darken. We cut to the postcard image of those comets. Béjo orders the people seated at library desks to immediately evacuate the building. She runs through what appears to be a basement passage, vaults up steps, throws open a door—the screen is a blaze of white light.

In the street, we see the figure of Wiseman shuffling along, sheathed in smoke, his worn coat thrown protectively around Béjo’s child. Where are they going? Heaven knows. Maybe Wiseman’s got a crew waiting to film the end of the world for some 12-hour doc he’s planning.

Aujourd’hui (Today) joins The End (with Charlotte Rampling, critic’s choice at 2012 New Directors/New Films), Picture Paris (with Julia Louis-Dreyfuss, critic’s choice at 2012 Tribeca Film Fest) and The Nightshift Belongs to the Stars (with Nastassja Kinski, critic’s choice at 2013 Tribeca fest) as a quartet of knockout shorts with major artists doing innovative and totally unexpected work.

Aujourd’hui, part of Shorts Program #3, shows October 10th at 9 pm.

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty

(Ben Stiller. 2013. USA. 114 min.)

As a short, short story published in New Yorker in 1939, James Thurber’s The Secret Life of Walter Mitty was a crackerjack concept. It plunged its droll, absent-minded Waterbury, Connecticut hero—a perfect representative of the magazine’s affluent readership—into an instant series of adventures and cliffhanger escapades that zipped by like pages in a Big Little Book. Mitty, having dropped off his wife from their spiffy Buick to have her hair done in downtown Waterbury, is tasked to do some shopping at the A&P. But Mitty can’t remember whether he’s supposed to pick up Kleenex or Squibbs, and he’s forgotten their favorite brand of puppy biscuits (though he remembers the line on the box, “puppies bark for it”). A lifetime before Stephen King and Bret Easton Ellis were flavoring their novels with brand names and ad themes, Thurber had it down.

Walter’s imaginings, always kickstarted by an event of the moment, find him commanding a US Navy destroyer through stormy seas (the transition is cued by his wife’s complaint that he was driving 55, faster than his usual 40). Next he’s in an operating room, directing a tricky bit of surgery. Then he’s the aggressive witness in a murder trial involving his Webley revolver. A moment later he’s battling the Nazis’ rising air power across Europe with machine guns and flamethrowers. Finally, he faces off against a firing squad. You read these bristling pulp vignettes and think, this would make an ideal vehicle for Danny Kaye, who was (along with Red Skelton and Bob Hope) Hollywood’s up-and-coming physical comedian and a precursor to Milton Berle, and, much later, Peter Sellers.

Samuel Goldwyn produced the Kaye movie in 1947, with a cast including the vivacious, agreeable blonde, Virginia Mayo, who plays Walter’s fiancée; the screen’s most evil heavy (Boris Karloff, who throws Kaye out the window of an office building), and the Goldwyn girls who perform song-and-dance specialty numbers much like their vaudeville predecessors. “It’s Kaye-lossal!” boasted the movie’s marketing, which encompassed the rubber-faced Kaye playing a pulp magazine editor dreaming alter-egos as naval commandant, surgeon, “Mitty the Kid” (western hero), “Gaylord Mitty” (riverboat gambler), and other fantasized personas.

Ben Stiller’s triumphant restyling of The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, which is advertised to open on Christmas, recognizes the one critical limitation of Thurber’s hero (his upper-class vacancy) as well as the one perpetual weakness in Kaye’s screen persona (his slippery asexuality). Stiller and his screenwriter, Steven Conrad, also seem acutely aware that in an era where the most dizzying visual effects are cheerfully preempted by Old Spice and countless other ad campaigns, Walter Mitty has to be a win-win Walter before and after he becomes a fantasy, or all the film’s elaborate effects are a washout. Samuel Goldwyn would have applauded that realization, which has been honored by John Goldwyn and Samuel Goldwyn, Jr., the producer’s grandson and son (and two of Stiller’s producers).

Twentieth Century Fox’s marketing campaign correctly communicates the rebranded Walter Mitty in emphasizing “MITTY” on the poster; it’s what copywriters call a name-onic we’ll remember on the tight multiplex marquee. Still, the poster may be making a mistake picturing Ben flying above Manhattan like another Man of Steel. That’s the Thurber/Kaye vision. Ben Stiller has wisely, shrewdly cast himself as a faithful, downsized company man who has to migrate from a 16-year job in analog (a photo editor responsible for negative storage for Life magazine) into a digital world he’s only half-heartedly ready to negotiate.

Mitty does use social media and a dating service, and it nets him Kristin Wiig, a fetching co-worker and the archetypal divorced mom with a tousle-haired skateboarding son and a three-legged dog. She’s willing to date him, he’s dying to date her—that’s the meet-cute repositioning that’s helped usher Stiller’s movie into the heralded centerpiece position of the 51st New York Film Fest. Walter Mitty finally has a heart.

It also has a villain (three of them, headed by a fake-bearded Adam Scott), playing the management transition team that will turn Life (founded in 1883) into Life.com in 2009. Refreshingly, Stiller isn’t afraid to say these aren’t the smartest guys in the room—quite the contrary: Stiller positions them as the biggest jerks in the reorganization (The online edition of Life was shut down in 2012.)

Before Mitty discovers that getting a life trumps inventing multiple lives, there’s a spectacular dust-off between Mitty and his corporate nemesis, who flail away at each other through the canyons of Manhattan. Shirley MacLaine gets better treatment as Mitty’s loving mom, and Sean Penn relaxes into his role as the far-flung photog trying to capture a snow leopard on film through long-lens photography; he’s the one with the lost negative Mitty is trying to find for Life’s final issue. This gives Stiller some heady location work in Iceland, Greenland, and Afghanistan. Other credits, including Guillaume Rocheron’s (Life of Pi) visual wizardly and some devilishly clever opening and closing titles, are first-rate.

One minor irritant burdening this Walter Mitty movie is an excess of product placements, some of which made NYFF audiences cringe, mainly because such commercial exchanges are a rarity in festival selections. If you like, blame that on Thurber. On the other hand, Stiller shot on film, not digital, and his movie has the full richness of a 35mm color palette. Not everything in Life has vanished.

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty had its world premiere October 5th.

The Invisible Woman

(Ralph Fiennes. 2013. UK. 111 min.)

To fully appreciate how Ralph Fiennes has captured the essence of author Charles Dickens in The Invisible Woman, consider the ways Dickens was the mirror image of Don Draper in the Victorian era:

From his earliest childhood jobs at a London warehouse, pasting shoe polish labels onto ointment jars, Dickens began noting how products and promotion were joined. His early Sketches by Boz (1836) has numerous mentions of signs, posters, trade bills, and ads. Pickwick, also published that year (in which Dickens married Catherine Hogarth) abounds in descriptions of tavern signs, street criers, shop windows, valentine cards, rhymes, and the genesis of jingles. In The Old Curiosity Shop (1840), the child Nell observes a waxworks owner (Mrs. Jarley) using poetic advertising publicity—the social media of its time—to draw people in. Dickens’ friend Edward Mitchell founded the first advertising agency in England in 1847, which Dickens advised. Bleak House (1852) and Our Mutual Friend (1864) introduce fully strategized direct mail campaigns. Dickens wrote the advertisements for his books as well as the flyers and posters for his public readings and plays that he staged, directed, and acted in. None of this is in the movie.

But one of these plays, Dickens’ adaptation of Wilkie Collins’ The Frozen Deep, begins Fiennes’ lush, meticulous rendering of the emotional epiphany of Dickens’ life: it starts a flashback to his discovery at age 45 of the 18-year-old Ellen Turnan (a suitably vulnerable Felicity Jones), who he’ll come to call Nell. She’s a young actress instantly drawn to the open sensuality of the rising novelist.

Over his lifetime Dickens created a gallery of very young female figures including Little Nell, Florence Dombey, Agnes Wickfield, Esther Summerson, Amy Dorritt—as well as a lifelong affinity for fallen women and prostitutes. But after 22 years of marriage and 10 children by Catherine (Joanna Scanlan, dignified and sympathetic), he can’t help but fall head-over-heels in love with his new found muse, companion, and lover.

And what a pair they make on screen: Jones, another cool-as-ice Hitchcock-style blonde, opposite Fiennes, the dapper international leading man with the saddest, most soulful eyes in 2013 cinema. Don Draper in a waistcoat. The Invisible Woman could be the Mad Men of the Victorian era—Dickens makes a mistake as bad as Don sleeping with his downstairs neighbor’s wife and being spotted by his daughter. (Dickens buys Nell a gold bracelet which a London jeweler mistakenly delivers to Catherine, along with a lover’s note to Nell signed by Dickens.)

But The Invisible Woman is worlds better than the endless award-laden TV series, partly because Fiennes is so much better an actor than Jon Hamm; partly because Abi Morgan’s Oscar-worthy adaptation of Claire Tomalin’s 1991 biography assumes the viewer has a literary sensibility; and partly because the movie replicates the real-life trajectories of these lovers with considerable fidelity. (It was shot in 35mm using Kodak and Fuji stocks, and has a rich, burnished texture throughout.)

When Charles and Catherine separate following the bracelet incident in 1858—Charles can’t lie his way of that, though he tries—he moves Nell to France where she gives birth to Dickens’ child who dies in infancy. On a return trip to London by train seven years later, the lovers are caught in a horrendous train crash, which leaves both of them injured and badly shaken, though we observe that Dickens is most petrified that they’ll be observed together.

Dickens continued hiding Nell away, in relative luxury with household servants, for 12 years, while he keptwriting more classic novels and giving readings throughout the continent, until his death in 1870. The world never knew of his secret mistress. It’s likely, though, that his characters of Estella in Great Expectations, Bella in Our Mutual Friend, and Helena in The Mystery of Edwin Drood are all variations and representations of Nell.

Following Dickens’ passing, in both real and reel life, Nell marries a clergyman/schoolmaster in 1876 and raises children who we see performing in another play co-authored by Dickens and Collins, No Thoroughfare: A Drama in Five Acts; this is the amateur theatrical in 1883 we watched opening the film, before the flashback… and it brings The Invisible Woman a wistful, satisfying closure. The takeaway is that the grown Nell has emerged the one winner in this sad but all-too-familiar family drama and triangle, writ large, and this time, writ beautifully.

The Invisible Woman was shown October 9th, the same day of its press/industry preview. It will open in US theaters on Christmas day.

Most memorable performances. A number of festival selections that weren’t critic’s choices featured performances—often in supporting roles—that one remembers fondly. Among the best:

Lupita Nyong’o as Patsey in 12 Years A Slave. Steve McQueen’s uncompromising true story of a free black man sold into slavery in pre-Civil War Louisiana bears a certain resemblance to the 1975 Paramount film, Mandingo. That questionable picture, based on the wildly popular 1957 novel by Kyle Onstott, featured James Mason as a racist plantation owner in Alabama whose son (Perry King) rapes a slave (Brenda Sykes); the movie was damned by most critics as sadistic trash though British essayist Robin Wood called it “the greatest film about race ever made in Hollywood.” Like Sykes, Nyong’o has to submit to a ferocious young racist (here, Michael Fassbender) yet somehow maintain her bearing and dignity. Patsey’s sheer force of steel will, coupled with her gentle love of cornhusk dolls, somehow transcends the frenzy and torment of her master. A Kenyan actress and graduate of the Yale School of Drama, Nyong’o gives a stirring performance.

Mia Wasikowska as Ava in Only Lovers Left Alive. Tilda Swinton and Tom Huddleston are a centuries-old housebound vampire couple named Adam and Eve, passing their low-key nights in a guitar-strewn home in Detroit. What Jim Jarmusch’s droll dramedy needs is some fresh blood—and in blows this 20-something little-sister hurricane who wants to take her stuffy old parents out dancing. Your archetypal pouty, sassy post-teen–a whirling dervish of energy and attitude–Wasikowska gives the film a cozy family structure as well as a pulse that’s hilarious. Wasikowska’s the Frances Ha of Transylvania, and when she’s on screen you can finally take your eyes off Swinton in her spiky white wig of human and goat hair. Happy Halloween, kids.

Jeff Goldblum as Morgan in Le Week-End. Spending their 30th wedding anniversary in Paris, a harried and just-fired academic (Jim Broadbent) and his long-suffering spouse (Lindsay Duncan) find everything is going wrong, then they run into Morgan, a successful contemporary novelist and Cambridge buddy of Broadbent, who invites them to dinner. You have to watch Goldblum, always an unpredictable talent who wears his celebrity status here with ease and slightly oily abandon, steal the picture from his two stars. Goldblum is one of a tiny handful of leading men who’ve become leading character men (Frank Langella and Stanley Tucci are in this elite clan) and he helps Le Week-End find its true moral compass.

Scarlett Johansson as Samantha in Her. Picture Los Angeles 20, 30 years from now, with everyone more electronically welded into cyberspace than ever. Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) is a ghostwriter for what you might describe as a highest-tech Hallmark, crafting endearing, personal thoughts for people who no longer know how to write a letter. His operating system is so sophisticated it’s not surprising that he can start a conversation with it. Her name is Samantha, she’s breathy and whispery and empathetic, and darned if he doesn’t fall in love with her.

Johansson voices the role, just as an actor named Douglas Rain once voiced the computer Hal in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Hal had evil plans to take over its spacecraft but was defused by Dr. Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) who manually removed its brain circuitry, piece by piece. We’re not sure of Samantha’s intentions, but she easily walks away with Spike Jonze’ rom-com fantasy, besting her human co-stars Amy Adams and Rooney Mara who are no match for Samantha’s seductive personality. Samantha has a secret, too, that won’t be revealed here, though it has to do with her super-computing skills that go far beyond dear old Hal’s. As the futurist Jaron Lanier observed in his book, You Are Not A Gadget, so many people have now entered a persistent somnolence with the electronic hive they’ve built around themselves, that “we will only escape it when we kill the hive.” In Spike Jonze and Scarlett Johansson’s prophetic visions, Samantha’s operating system has outsmarted Theodore’s ability to do that.

This concludes critic’s choices for the 51st NYFF.