NYFF 2015: Critic’s Choice

Kurt Brokaw's favorites from the 2015 New York Film Festival.

Each year, senior film critic Kurt Brokaw watches the entire New York Film Festival slate in order to choose the best and brightest. This year’s festival runs from September 25th through October 11th.

The Walk

(Robert Zemeckis. 2015. USA. 124 min.)

There’s storydoing, and there’s storytelling. This review of The Walk will define one historic New York event documented and dramatized in two very different movies.

StoryDoing (the term was invented and trademarked by ad exec Ty Montague) is what you post in the social media that brand your life every day: Vine, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, et. al. Boyhood, this writer’s number one American film last year, turned traditional storytelling into untraditional storydoing; in this dramatic memoir, you watched a boy, his sister, and their parents age 12 years before your eyes in a few real-time hours.

Philippe Petit’s 2002 book, To Reach The Clouds, was the nail biting diary of his step-by-step, year-by-year planning and execution of his wire walk between Manhattan’s Twin Towers in 1974. It inspired James Marsh’s 89-minute documentary, Man On Wire (2008), which filmed Petit and members of his original team re-creating the smuggling of the 450 lb. cable, 55 lb. balancing bar (in pieces extending to 26 feet) and other gear to the top floor of one tower, the night before.

This was storydoing. The documentary included footage of “test crossings” at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris in 1971 and Harbor Bridge in Sydney in 1974. It showed the childlike imagination and devotion of Petit and company in constructing scale models of the towers, calculating wind velocities, enlarging photos to evaluate anchor points, and even watching scenes from a 50s heist movie, Kansas City Confidential.

And then, as in the comic crime novels of Lawrence Block and the late Don Westlake, it showed how everything went wrong. One crewmember turned up stoned. Several more bailed out. On the roof during the night, the setup for the walk wire started with a fishing line that was propelled across the towers by bow-and-arrow, and Petit couldn’t find where either had landed in the dark. Then a length of heavy cable fell off one side of the tower and had to be painfully hoisted back up, foot by foot by foot. Petit himself had a split second of doubt at dawn when he first inched one leg off the ledge and onto the cable that was finally stretched taut 1,350 feet above the ground.

Man on Wire showed Petit make the cross and back eight times, but we watched via a few still photos—there wasn’t a single movie or video camera among the NYPD forces gathering on the roofs or in overhead police helicopters. In this pre-Internet world, no one in the crowd below had a movie or video camera, either. And of course, no one had a “smart” phone. Marsh’s storydoing doc remains forever stuck, frozen in time. In a way, his movie ends without ever truly beginning.

Nonetheless, the event was a win-win for Petit and for New York. The aerialist’s arrest charges were quickly dismissed and he was given a lifetime pass to the towers’ observation decks, eventually becoming artist-in-residence at Manhattan’s magnificent Cathedral of St. John the Divine. But anyway you look at it, Marsh’s film is a muted victory, because you’re aching to view Petit walk the talk by walking the wire, and the footage just doesn’t exist.

Cue Zemeckis. His triumphant opening night spectacular at this 53rd NYFF gives you nearly all the tactical buildup and cliffhanger moments of Marsh’s documentary, plus the big payoff. In IMAX 3-D, it’s an unimaginably big and gaspingly thrilling payoff—you really do “experience the impossible,” and for once, a movie poster theme line doesn’t exaggerate. In all the 3-D movies made since 1953, the reality/illusion of depth has never been so scarily and convincingly put on any screen.

Watch: Robert Zemeckis, Joseph Gordon-Levitt & Cast Discuss The Walk:

The director is one of cinema’s master storytellers (Forrest Gump, The Polar Express, Castaway, Flight—a pick from NYFF 2012), and this is the movie that pulls out all the seamless effects tricks from his magical movie making trunk. Nearly every major artistic decision made by Zemeckis pays off. He lets the jaunty and unfailingly optimistic Joseph Gordon-Levitt, playing Petit, be the storyteller/narrator, placing him throughout the escalating tension beside the torch up in the Statue of Liberty, with the towers as a distant backdrop. He casts a pleasing supporting stock company headed by Ben Kingsley as Petit’s French mentor and Charlotte Le Bon as his so-sweet Parisian busker. His pacing kicks along with the assurance of a Spielberg thriller, all framed with a family-friendly PG rating just like Scorsese’s Hugo.

The Walk is a daring affirmation by NYFF’s curators that Opening Nights can celebrate movies with unlimited global appeal—movies that can win Oscars (maybe even a Best Picture here) as they delight children of all ages. Storytelling is alive and well at Lincoln Center.

The Walk had its world premiere at Alice Tully Hall on September 26th.

Journey to the Shore

(Kiyoshi Kurosawa. 2015. Japan/France. 127 min.)

Reincarnation dramas cling to a more rigorous aesthetic than any other filmic drama. The director must first win the viewer’s suspension of disbelief—as many films in most genres always have—but in back-from-the-dead stories that ask to be taken seriously, the director can’t let that persuasive artistry flag for a second.

In short, embracing what our eyes and mind automatically challenge is no easy task to sustain for more than two hours. The last drama to fully achieve this belief-in-the-unbelievable was Clint Eastwood’s Hereafter (2010). Hailed by The New York Times’ chief film critic as having “the power to haunt the skeptical, to mystify the credulous and to fascinate everyone in between,” Hereafter starred Matt Damon as a laborer who could receive messages from the dead loved ones of anyone he touched.

Kurosawa’s Journey to the Shore, a drama of a Japanese couple rediscovering each other after the husband’s death, is simpler to grasp and more lasting in its gentle reveries. Mizuki (Eri Fukatsu, sublimely modest) is a children’s piano teacher, widowed for three years after Yusuke (Tadanobu Asano, quietly handsome) disappeared at sea, his body never found. One night he simply walks in out of the shadows into their living room.

After reminding him to take off his shoes (the things husbands forget!), Mizuki shows him 100 copies of a Shinto prayer she’s dutifully copied, hoping he would be somehow, somewhere safe. He tells her his body was devoured by crabs, though he looks none the worse for wear. Kurosawa’s lighting and pacing are delicate and considered; he’s shooting in CinemaScope which lets the couple stay at a polite remove from each other. There’s no wild embrace; there’s no embrace at all for a very long time.

Yusuke’s plan is to take his wife on a journey back through his life, by train and bus, to review places and people that were meaningful in his earthly existence. Their first stop is a rural town (Yaga, south of Tokyo) and the office of a pleasant, older community newspaper publisher, whose wife is similarily missing. But as she observes her husband’s mentor folding his papers and cutting out wallpaper flowers, we come to understand that the publisher, too, has perished—and briefly we slip into a past in which his home in Yaga was devastated by a storm or tsunami.

At their next stop, Yusuke goes to work in a restaurant as a gyoza-maker, preparing the little cakes Mizuki knows he loved so much. The teacher finds a piano and plays “Harmony of the Angels,” and then supervises a schoolgirl, who has also died, learning the same piece. Kurosawa begins playing with unexpected lighting shifts here, as well as the occasional optical removal of characters. Nothing is forced and we transition smoothly from one subconscious current to another that the director is carefully releasing.

Traveling by bus to a medical clinic in which Yusuke once practiced, Mizuki has uncovered evidence on a computer that her husband was having an affair with an employee, Tomoko (Yû Aoi, perfectly cast as a younger version of Fukatsu). The two women meet and Tomoko quietly reveals she is married and pregnant and about to leave working life altogether.

Meanwhile, Yusuke returns to a village where he once taught the science of light, slipping confidently back into a lecture in which he stresses that nothingness (perhaps his state now) does not equal meaningless. That night, Mizuki confesses to a four-year college romance she deeply enjoyed before meeting Yusuke, who she would marry and remain faithful to.

Their final destination is a mysterious waterfall deep in a woods backed up by a dark cave. The cave represents a gateway to heaven, where the living disappear into another world—in Buddhism a “yonder shore”—a journey that transitions the dead into resurrection and a new, better life. Here Mizuki reunites with her own father, who became ill and died at 16, now an old man living at peace.

“I didn’t want to die,” Yusuke later tells his wife, though by now we’ve been given enough information to conclude that depression probably fueled his suicide. She forgives him, and their mutual humility, gratitude and acceptance draw the couple together into an intimate embrace. All the copies of her prayer, now fulfilled, can be burned.

Journey to the Shore has a deeply satisfying resonance through all its 127 crafted minutes. It’s the flip side to another reincarnation film on view at this festival, a droll comedy made 75 years ago—Ernst Lubitsch’s Heaven Can Wait, a 20th Century Fox revival, its lush 35mm Technicolor print restored by Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation.

In its pre-Depression view of a moneyed, privileged Fifth Avenue social set, playboy Don Ameche has died and is at hell’s Deco-styled door, presided over by its pasty HR director (Laird Cregar,). Laird’s bearded devil is taking Ameche’s inventory, which spins us into a biopic of an unfaithful rogue who marries Gene Tierney and then dailies with a slick showgirl (Helene Reynolds) who extorts $25,000 in return for not wrecking his marriage. Ameche dies of exhaustion at 70-plus and gets a pass out of hell, though not necessarily a passport into heaven. This is an early demo, confirmed in Kurosawa’s movie many generations later: that it’s not just bad girls who get to go everywhere—flawed guys get their second go-arounds, too.

Journey to the Shore shows Tuesday, September 29th at 6 pm in Alice Tully Hall, and Thursday, October 1st at 6 pm in the Elinor Bunin Monroe theaters in Lincoln Center.

Sundae

(Sonya Goddy. 2015. USA. 7 min.)

Short subjects with a true conceptual twist are a rarity. Adding a coda ending that makes you rethink everything you’ve watched almost never happens. Sonya Goddy, a freshly minted Columbia MFA graduate, shows you how it’s done.

We’re behind the wheel cruising a residential neighborhood of old homes, with a mom (Finnerty Steeves) and her bright 5-year-old (Julian Antonio de Leon) looking for what the boy remembers as a large yellow house. Why? We don’t know. But the distraught mother promises her son a sundae with all the fixin’s if he recognizes the house.

A big yellow home pulls into view. The child signals that’s the one. Mom turns off the ignition, marches up to the door and rings the bell. An attractive woman opens the door. Mom wallops the woman with the hardest punch she can throw. Then she hurries back to the car, takes out a large red brick and hurls it through the picture window. She and her son drive off—and discover a scene not too far away that instantly clarifies the woman’s anger and rage.

The boy quietly spoons in his mammoth sundae. But then he tells mom something she (and we) never expected to hear—the coda closer. This all happens in a neat-as-a-pin seven minutes. Goddy’s short has already won the Adrienne Shelly Foundation award for best female director. Its originality tops even Pixar’s streamlined seven-minute animation short (Sanja’s SuperTeam) that probably cost a zillion times more. Goddy’s on her way.

Sundae is part of Shorts Program #4 (“New York”).

Tops in Docs

The documentary scene extends from international luminaries (Ingrid Bergman In Her Own Words) to unknown family members like the mom of fest director Chantal Akerman’s mom (No Home Movie). Three top this critic’s list:

De Palma

(Noah Baumbach, Jake Paltrow. 2015. USA. 107 min.)

Seated slightly above eye level, the quintessential film lecturer in casual black, Brian De Palma at 73 easily holds your attention and interest, collapsing his life’s story and work (39 films and counting) into his own two-hour narrative. Several lessons emerge: First, collaboration and playing well with others can turn an iconoclastic maverick into a reliable, accepted denizen within the studio system (it helps if you marry Gale Anne Hurd) who got mostly A-level projects green-lighted, with the paydays to match.

The second lesson is that crafting your own gigantic set pieces with split-screens galore and swooping cranes can give you branding spurs as vivid as any Hitchcock MacGuffin. Think Tony Montana’s M16A1 machine-gun/grenade-launching, “little friend” demise in Scarface… that baby carriage with its grinning infant tumbling down Potemkin’s Odessa steps in The Untouchables as bodies pile up right and left… the camera endlessly tracking Angie Dickenson at gorgeous knee level through the Museum of Modern Art in Dressed to Kill… the subway-car-to-car-to-car pursuit of Pacino in Carlito’s Way… the over-the-roof craning in The Black Dahlia to the halved body below… all that pig’s blood drenching poor Sissy Spacek in Carrie… oh-my-God-the-power-drill-going-through-Gloria-and-the-whole-damn-floor-into-the-apartment-below in Body Double. That De Palma just never knows when to stop.

The third and most important lesson is never giving up—De Palma proves he can take a lickin’ and keep on tickin’. Directors Baumbach and Paltrow are betting this edgy outlaw will walk away with your unreserved admiration. All those Razzie nominations, all those accolades and praise from Pauline Kael—De Palma takes it all in stride.

De Palma shows Wednesday, September 30th at 6 pm in Alice Tully Hall.

Everything Is Copy

(Jacob Bernstein. 2015. USA. 89 min.)

The key requirement of biopics on Manhattan icons is that they gotta get not just the subject but the city right. Most do; the three most recent successes are Iris, Koch and Bill Cunningham New York. Add Jacob Bernstein’s lovingly critical examination of his mother, Nora Ephron in Everything Is Copy, to the list. She was our literary star (1941-2012) until she was felled by a blood disease and leukemia, and the film and publishing roster assembled to salute her accomplishments—book by book, film by film, husband by husband—couldn’t be better curated.

Streep, Hanks, Reiner, Nichols, Walters, Dunham, Balaban, Spielberg, Diller, Talese… Meg Ryan, Rita Wilson, Lynda Obst, Amy Pascal, Liz Smith, Nora’s three sisters (Hallie, Delia, Amy), her book editor Robert Gottlieb, her New York magazine editor David Remnick, her writing pal Marie Brenner, her first husband Dan Greenburg—everyone is on point, offering their most intimate insights without dishing or pretense. The one key person missing on camera is her third husband, author/screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi.

It was Nora’s mother, Phoebe, who said “everything is copy,” advice her daughter took to heart without ever falling into Joan Didion’s more fatalistic trap that “people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests. And it always does—writers are always selling somebody out.” And Nora never did that. Well, almost never.

The one gloomy Gus on camera—sitting uncomfortably like a grandly collapsed 71-year-old monarch—is the director’s dad and Nora’s second husband, Carl Bernstein. He’s the one villain in the doc. For it was Bernstein who betrayed Nora, and she responded with a tell-all novel (Heartburn) that became a tell-all movie (Heartburn) that looks like it’s giving the Pulitzer Prize winning journalist a case of heartburn that won’t go away in his twilight years. “I didn’t want that movie made,” he grumps. He doesn’t look like he’s thrilled his son is making this movie, either. But you will be.

Everything Is Copy shows Tuesday, September 29th at 6 pm and Saturday, October 3rd at 12:30 pm in the Walter Reade Theater.

Don’t Blink – Robert Frank

(Laura Israel. 2015. USA/Canada. 82 min.)

Who’s the fly-on-the-wall photographer that’s most engaged and enlarged a film fan’s cultural perspectives? Your list might start with New York street photographers like Arthur “Weegee” Fellig, Vivian Maier, James Van Der Zee, Gordon Parks, Cornell Capa and the Village Voice’s Fred McDarrah—all chroniclers of gritty New York and its residents, indoors and out. If Robert Frank’s work doesn’t come immediately to mind, spending 82-minutes with Laura Israel’s smashing new doc is sure to embed him in your short list.

Born in Zurich in 1924, Frank joined Harper’s Bazaar as a fashion photographer in 1945. (“All the commercial world we’d call Sammy,” he says, echoing Budd Schulberg’s movie hustler in What Makes Sammy Run?) His first group show was at The Museum of Modern Art four years later, followed by a two-year road trip across America in the mid-50s in which he took 28,000 shots. Grove Press published his landmark book The Americans in ’59—83 photos of people on the edges of despair and ruin, in taverns, in front of battered TVs. Janet Malcolm called him “the Manet of the new photography.” Frank’s key mentor was probably Walker Evans, the preeminent chronicler of the Depression era. “I think I always had a cold eye,” he admits.

At that pivotal moment following the acclaim for The Americans, Frank walked away from photography to begin an improvisational film career celebrating the burgeoning counter-culture. He collaborated with Jack Kerouac (plus other Beat icons Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky and Gregory Corso) on the indie classic Pull My Daisy, and About Me: A Musical, an autobiographical tract in which he’s played by the actress Lynn Reyner. Incongruity and unpredictability are among Frank’s signature devices.

Influenced by members of the New American Cinema Group including Shirley Clarke and Jonas Mekas, and fascinated by what Susan Sontag called “the insignificant detail,” Frank also created the infamous (and largely unseen) Cocksucker Blues doc of The Rolling Stones getting high and masturbating, which was banned by The Stones who feared they wouldn’t be allowed back in America if the film was distributed. (Frank did their LP cover of Exile on Main Street.)

Israel’s doc is also an investigation into Frank’s creative process—the intricacies of how he works (fast, the first shot often is the keeper) and how he engages subjects (not much, if at all), plus his methods and explorations in developing and enlarging, scratching negatives, mixing black-and-white with color. Israel’s cameras—with the ace cinematographers Ed Lachman and Lisa Rinzler sharing DP duties—love rummaging through what feel like 28,000 tiny snaps to big Polaroids, perusing contact sheets, unexpected compositions, croppings, reactions, discovering scenes of “emotional urgency” once demanded by photo editors that could stop and surprise viewers.

Israel’s doc is scored to one of the most tightly curated music collages you’ve ever heard—The Velvet Underground to The White Stripes, Johnny Thunders to Patti Smith. Much of the action takes place in his isolated Nova Scotia home, which he shares with his wife, painter/sculptor June Leaf. He has donated over 3,000 sheets of negatives, 1,500 contact sheets and 1,000 vintage prints to the National Gallery.

Frank expressed an abiding philosophy in an early film: “I’m always looking outside, trying to look inside. Trying to tell something that’s true. But maybe nothing is really true. Except what’s out there—and what’s out there is always changing.” At 90, one of the last living Beat Generation originals with a Swiss pedigree, Frank is still changing it.

Don’t Blink – Robert Frank shows Sunday, October 4th at 3 pm at Alice Tully Hall and Tuesday, October 6th at 6 pm in the Monroe theaters.

Carol

(Todd Haynes. 2015. USA. 118 min.)

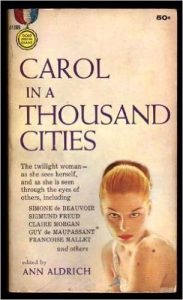

“I call her Carol, but her name may be your name, or the name of your sister, your daughter, your wife, your mother, your roommate, your neighbor, your lover. Carol is the lesbian in our midst, and her name is legion.”

Above is the moving introduction by Marijane Meaker (writing as Ann Aldrich, one of her four pen names) to her 1960 anthology of lesbian fiction and nonfiction, Carol, In A Thousand Cities, a 50-cent paperback original published by Gold Medal books. Meaker was Patricia Highsmith’s lover from 1959-61; they shared a rural home in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, after Highsmith had written The Price of Salt, which appeared in the 25-cent Bantam paperback.

Both the 1952 hardcover and paperback carried Highsmith’s pen name, Claire Morgan, and she describes her novel as “having become famous for its ‘happy ending,’ published as it was among dozens of novels of male and female homosexuality that wound matters up with sleeping pills, murder, imprisonment, unbelievable self-conversion, or the corpse in the swimming pool.”

Both the 1952 hardcover and paperback carried Highsmith’s pen name, Claire Morgan, and she describes her novel as “having become famous for its ‘happy ending,’ published as it was among dozens of novels of male and female homosexuality that wound matters up with sleeping pills, murder, imprisonment, unbelievable self-conversion, or the corpse in the swimming pool.”

In Todd Haynes’ exquisitely refined adaptation, Carol (adapted by Phyllis Nagy; one of the producers is Christine Vachon), Carol is a married suburbanite with a seven-year-old daughter who’s staying with her incompatible husband’s family. Carol is played by Cate Blanchett, who’s groomed and compressed her usually buoyant screen persona into a calculating lady-of-leisure in fur coat and black suede pumps, a decade younger. She’s seeking a divorce while trying to gain custody of the child, having shed an intimate relationship with her daughter’s godmother (Sarah Paulson, mature and saddened as the dumped lover who holds onto her dignity). Playing the grim husband who understands he’s losing his wife but can’t fathom her attraction to a woman, Kyle Chandler is the perfect, pained foil.

It’s Christmas in the big city, and Haynes has fashioned New York’s stores, restaurants and avenues with a subdued holiday delicacy that’s softly luxurious—even more cocoon-like with Ed Lachman’s lensing (in Super 16mm) that imbues every scene with a muted velvety texture of old money and class. It’s a Manhattan that seems to exist today only in Ralph Lauren and Bergdorf Goodman’s windows, and it’s sumptuous.

The plot, which adheres closely to Highsmith’s novel, is deceptively simple. Carol’s epiphany occurs as she’s shopping for her daughter at a department store and is struck by the salesgirl behind the doll counter. She’s Therese (Rooney Mara, who at 30 can still play 20 without a trace of guile and will instantly remind you of a coltish Audrey Hepburn). Carol orders the most elaborate train set in the store, conveniently leaving her gloves for Therese to find and return.

In short order, their friendship evolves into Carol tootling off with her young protégé on a road trip in her 1949 Packard, through the Midwest. Their couplings are ravishingly discrete, reflecting the subtle 50s eroticism in early lesbian fiction that kept publishers like Gold Medal and even Bantam fretting whether explicit paperbacks would be seized by interstate postal authorities. The novel and the film run into a similar calamity when Carol and Therese are blindsided by a young chap who comes on as a lothario but is something far darker. His actions force Carol to return home, abandoning Therese.

But not forever. Not, even, for that long. Carol and her husband sell their home, she takes an apartment on upper Madison Avenue, goes to work as a buyer for a Fourth Avenue furniture house. Therese has found her niche in photography. And one night Therese visits the elegant restaurant where once she took tea while Carol sipped martinis. Here are Patricia Highsmith’s final sentences:

“She stood in the doorway, looking over the people at the tables in the room where a piano played. The lights were not bright, and she did not see her at first, half hidden in the shadow against the far wall. …Carol raised her hand slowly and brushed her hair back, once on either side, and Therese smiled because the gesture was Carol, and it was Carol she loved, and would always love. …It would be Carol, in a thousand cities, a thousand houses, in foreign lands where they would go together, in heaven and in hell. …Carol saw her, seemed to stare at her incredulously a moment before Therese watched the slow smile growing, before her arm lifted suddenly, her hand waved a quick, eager greeting that Therese had never seen before. Therese walked toward her.”

Carol is, at this point, the best drama in New York’s most closely watched film festival.

Carol shows Friday, Oct. 9th at 6 pm and Saturday, Oct. 10th at 2 pm in Alice Tully Hall, and Sunday, Oct. 11th at 6 pm at the Walter Reade Theater.

Steve Jobs

(Danny Boyle. 2015. USA. 125 min.)

It’s January 24, 1984, and Apple’s head (a lazer-beamed Michael Fassbender who never smiles in anything but triumph) is pacing backstage, waiting to go on to a capacity audience of eager shareholders in Cupertino, California’s performing arts center. Everything is annoying this mercurial perfectionist, but three issues are top of mind: Time Magazine, instead of picking its usual Man of the Year in 1982, which Jobs figured would be him, pictured a sculpted dummy in front of a generic computer (“Machine of the Year”); Jobs wants no part of this and orders his long-suffering marketing chief, Joanna Hoffman (Kate Winslet in a lightning-fast, career-topping performance) to get rid of all the reprints she’s ready to distribute to the crowd.

The second intrusion is his long-suffering ex-girlfriend, Chrisann Brennan (Katherine Waterston, carving another notch in a luminously growing list of credits) who’s cooling her heels backstage with their six-year-old daughter in hand, Lisa (Makenzie Moss), demanding her $385 monthly check, as mother and child are surviving on welfare. Jobs brushes them off, even though DNA testing has revealed a 94.4 percent chance that he’s Lisa’s dad, which Jobs has reinterpreted to mean that 28 percent of the male population in the United States could have impregnated Chrisann.

Jobs’ third worry is the 60-second Macintosh teaser spot commercial ready to break on the ’84 Super Bowl. The one person on Apple’s management team who gets the spot (and even offered to split the $1,000,000 network cost with Jobs, though this isn’t in the movie) is his founding partner Steve Wozniak (Seth Rogen, beautifully humane as Jobs’ tech brain). Few others in the boardroom even understand the strange sight of a hall of skinhead zombies filing in to watch a Big Brother figure on a giant screen reading from George Orwell’s prophetic 1949 novel, 1984. This is a teaser commercial for the Super Bowl?

The ad is worth another look-see, because it signals the first mass media branding of Apple’s product lines as well as its fiercely independent leader who would forever “Think Different.” In ’84 office managers who bought computer equipment knew they’d never lose their jobs ordering IBM’s Big Blue; it was a common mindset represented in the ad by the prison-suited loonies photographed in monotone. In runs this gorgeous gal in living color, a real-life Apple metaphor wielding a hammer, which she flings at the screen image, obliterating big bad government and the category leader, big bad IBM. And the announcer intones Macintosh’s impending arrival, so “1984 won’t be like 1984.”

See for yourself:

Jobs had to have sensed—pushed along by his trusted buddy Lee Clow (now 72 and an early Venice/Malibu surfer) who was creative head at his ad agency, TBWA/ Chiat/Day—that the Super Bowl audience would long remember a commercial few viewers would consciously understand. Directed by Ridley Scott, who had Alien and Blade Runner running in theaters, the commercial didn’t look, sound or feel like any other television commercial in the history of the medium. But it looked, sounded and felt like those groundbreaking movies, which is why it became the 20th century’s killer commercial.

Danny Boyle’s shock-and-awe Steve Jobs—and it is that, every bit as pulse pounding and hair-raising as this festival’s wire-walking opener—has the same adrenaline-stirring urgency of Scott’s movies and his Macintosh commercial. With Boyle, the experience has this difference: it’s like watching an angrier Birdman on steroids. Aaron Sorkin’s bullet-hard adaptation of Walter Isaacson’s 630-page Jobs’ biography collapses the Jobs footprint into three 40-minute, real-time behind-the-scenes dramas: right before the Macintosh intro in ’84… right before the launch of the NeXT ‘Cube’ in ’88… and right before the iMac announcement in ’98. Backstage, backstage, backstage. This screenwriter perfectly understands the value of repetition, just as advertisers do.

Sorkin elects to show this testy entrepreneur almost entirely at his brilliant worst—a maniacally driven inventor and marketer with zero patience, a hair-trigger temper and an implacable mastery of logic and engineering whose arguments could demolish anyone daring to challenge his master-of-the-world reasoning. Sorkin played that card with Jesse Eisenberg acting Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network. In a way, Jobs is the same exec who’s locked-and-loaded 24/7, a zealot without much of a heart. (Albert Einstein was Jobs’ garage hero growing up, and Einstein leads the parade of living and dead celebs in the company’s “Think Different” ad campaign, probably standing in for Jobs.)

In the final minutes, Sorkin, perhaps aware of producer Scott Rudin worrying about no one lining up to pay money to watch these punishing diatribes, humanizes Jobs with his grown-up Lisa (Perla Haney-Jardine) in a few shimmering minutes, knitting together a reconciliation between father and daughter. But it’s probably too little, too late. You’ll walk out with an intense distaste, maybe even a Michael Moore hatred, for corporate America. Still, anyone who’s spent a lifetime prowling through Fortune 100 corridors and cultures knows any numbers of Jobs’ wannabes, and if anything, most are even meaner and not a fraction as smart.

Boyle’s ensemble cast works like a top-of-the-line iMac or the super trained, super smart young teams lining Apple’s Genius Bars across America. Jeff Daniels is continuously effective as John Sculley, Apple’s CEO, the exec Jobs hired away from Pepsi because Sculley understood that hard-edged, celebrity-driven advertising was Pepsi’s most effective creative weapon against Coke’s more traditional, warm-and-fuzzy imagery. Michael Stuhlbarg scores big points as Andy Herzfeld, who’ll be remembered not as the Mac software designer but as the Jobs’ loyalist who paid Lisa’s college tuition because Steve didn’t have the time or maybe even the inclination to take care of this task. Does Jobs thank him? No, he condemns Herzfeld for butting in, and also for recommending a therapist for Lisa.

Like The Social Network, Steve Jobs paints an unrelentingly grim portrait of how business leadership developed in the frontier days of the Internet. Eisenberg and Fassbender are hugely skillful actors, and they’ve been scripted and directed as coldly cerebral entrepreneurs—creatures almost without souls. This is a far cry from, say, Jon Hamm’s Don Draper in Mad Men, who for seven years held television audiences as a second rate pre-Internet ad man and philanderer who drank away a couple of promising careers. Draper was far easier to like because he wore his flaws on his sleeve. Jobs, like Zuckerberg, worked in the ether, which is why Sorkin/Boyle’s backstage world closely resembles a true hell on earth.

Miles Ahead

(Don Cheadle. 2015. USA. 100 min.)

Steve Jobs and wire-walker Philippe Petit aren’t the only visionaries whose lives have been compressed into a few revealing pieces in this festival. The most turbulent period in trumpet virtuoso Miles Davis’ (1926-1991) career was when he’d stopped recording in the late 1970s. In Don Cheadle’s bristling and sometimes harrowing hybrid of real and fictionalized events, Miles Ahead, the director/star powers up a jarring portrait of the artist in disarray, from addiction to eventual transition from hard bop to jazz/electronic rock.

Like Jobs in Steve Jobs, the musician we view is pissed off at a long list of people. Davis starts with a phone rant at Phil Schaap, WKCR’s beloved radio host and jazz historian in New York, who’s playing an older album Davis considers obsolete. (He wants to hear his ’75 Osaka concert.) He’s also mad as hell at his label, Columbia Records, where he made 44 albums over 29 years, for withholding monies he says are long overdue.

And he gets really steamed when a sleazy reporter, Dave Brill (Ewan McGregor, wonderfully wasted), who says he’s with Rolling Stone, barges into Davis’ five-story townhouse, begging for an interview. The musician was living on West 77th Street in a former Russian Orthodox church he’d converted, with a gigantic lux sunken living room, animal skins covering the floors and a stereo system in the walls. Davis was plagued by sickle cell anemia and a degenerative hip disease, and he had uncertainty about where to take his “social music” (he steadfastly refused to call it “jazz”). Davis agrees to talk to Brill only when the writer offers to drive him to a first-rate Columbia University drug dealer.

Wait, it gets worse. The white student dealer jacks up the price on his pure cocaine, and talks Miles into signing some rare LPs to make up the difference. Then, during a raucous house party his ex-wife Frances (Emayatzy Corinealdi) is throwing, a master tape of experimental music Davis has been recording disappears. Maybe a Columbia producer (Michael Stuhlbarg) knows where it is. Maybe the producer or Brill has stolen it. Davis is frantic, guns are drawn, shots are fired, there’s a car chase. The hunt is on.

Wait, it gets worse. The white student dealer jacks up the price on his pure cocaine, and talks Miles into signing some rare LPs to make up the difference. Then, during a raucous house party his ex-wife Frances (Emayatzy Corinealdi) is throwing, a master tape of experimental music Davis has been recording disappears. Maybe a Columbia producer (Michael Stuhlbarg) knows where it is. Maybe the producer or Brill has stolen it. Davis is frantic, guns are drawn, shots are fired, there’s a car chase. The hunt is on.

Director Cheadle says his movie (co-written with Steven Baigelman) “isn’t a biopic, per se. It’s a gangster pic. It’s a movie Miles would have wanted to star in.” Probably that’s true, because the 30-second bio Davis gives Brill in the musician’s raspy whisper (“moved to New York, met some cats, made some music, did some dope, made some more music”) wouldn’t have made much of a date night at the multiplex. Cheadle wanted “truths, not just facts.” He wasn’t shy about turning to IndieGoGo, the crowd funding website, to help raise a piece of the $8.5 million budget to make the film he wanted to make. Cincinnati stands in for a long-ago Manhattan, as it did in Carol.

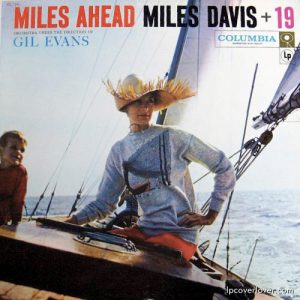

Davis’ testy relations with Columbia Records are well documented, though Cheadle omits his greatest humiliation with the label—the initial release of “Miles Ahead” in 1957 (on which Davis plays flugelhorn exclusively) used an LP cover photo of a white woman and child basking on a gleaming sailboat. It also holds back on the disdain Davis felt toward white musicians (he hated the fusion band Blood, Sweat and Tears, a Columbia chart-topper) and his dislike of inattentive white audiences he increasingly played to in the 80s.

None of his seminal session work with Charlie Parker at Birdland on West 52nd Street is alluded to—it’s where Davis first fell to hard drugs along with saxophonist Gene Ammons—but Cheadle includes a bloody night when Davis was headlining at Birdland and was beaten and arrested by NYPD for “loitering” on the sidewalk outside the club. Little wonder Davis titled his last album for Columbia “You’re Under Arrest.” His antipathy toward a white world is painfully rendered.

But his standalone musicianship is movingly documented in Miles Ahead. Davis led numerous small and large groups, and his commanding grasp of charts and arrangements was peerless. The contributions of Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter and other legends, along with co-music composer/pianist Robert Glasper, are strongly felt in the film. “You teach and it comes right back to you,” Davis once said. “I show Herbie something, or Wayne, and they’d take it further. It’s like pressing a crease in your pants, only somebody continues with the iron.”

Cheadle’s movie could have used more of the soft, ruminative poet that ringed much of Davis’ aesthetic, and less of the noisy theatrics (Cheadle’s whiplash editing, his disorienting see-sawing between past and present) that threaten to overwhelm and even derail his storytelling. Miles Ahead is a worthy close to this 53rd NYFF, but as Bette Davis once warned, “fasten your seatbelts, it’s going to be a bumpy night.”

Miles Ahead had its world premiere at Alice Tully Hall on October 3rd.

This concludes critic’s choices. Next up: DOC NYC, November 12-19, 2015.

Editor’s Note: When originally published on September 29, 2015, this story incorrectly credited ad executive Eric Weisberg with coining the term “story-doing.” A change was made September 30, 2015 to accurately credit Ty Montague.

Regions: New York City