New York Film Festival 2016 (Sept. 30-Oct. 16)

Senior film critic Kurt Brokaw views the entire Main Slate and selects his favorites from the 54th NYFF

Moonlight

(Barry Jenkins. USA. 2016. 110 minutes)

“Film Lives Here” is the theme of the Film Society of Lincoln Center, its 54th New York Film Festival, and its flagship Walter Reade Theater. “Film Lives On Here” would be just as apt. It’s possible your movie sensibilities were shaped by Richard Roud’s curatorial leadership starting in 1963. Roud was a Europhile, most remembered for introducing American audience to the French New Wave. But his second 1964 fest also introduced a largely white Manhattan audience to the African-American experience.

Michael Roemer’s Nothing But A Man was a game-changer of the first order. It starred Ivan Dixon as a gruff railroad laborer who marries a lithesome Baptist preacher’s daughter (a stunning Abbey Lincoln). Roemer’s drama, while gritty, was always considered and reflective—it dug deep into racial conflicts as well as class differences and allegiances in the black community that mixed audiences had never experienced. After its NYFF and Venice debuts, the picture languished in obscurity; Roemer and Robert Young’s screenplay was novelized in 1970 as a 60-cent Popular Library paperback by Jim Thompson, the noir writer whose usual specialty was crafting goofball psychopathic killers. At the 50th NY film fest, Nothing But A Man was newly revived as a Masterworks selection, with Roemer and Young attending.

Moonlight, the new film by Barry Jenkins, is another transforming experience, this time for far more inclusive audiences. Jenkins could have titled it “Nothing But A Gay Man” because that’s its Twitter-style essence. It follows the childhood, teen years and transition into adult life of Chiron, a shy Miami native whose hardscrabble life is consistently challenged by adversity but equally supported by reflection, kindnesses and understanding. The picture is led by three stellar actors—Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders and Trevante Rhodes—each playing Chiron in the movie’s three chapters which are set in ’80s and ’90s Miami.

The pivotal troubling influence intersecting the boy’s growth into manhood is his mother, Paula. She’s a volatile drug addict and she’s played alternately sullen and alluring, with sudden bursts of instability and fury, by Naomie Harris. She’s as wired, jittery and nerve-jangling as Ms. Lincoln was calm, cool and collected a half century ago.

The critical counterbalance who gains Chiron’s affection and guides him into maturity is Juan (Mahershala Ali). He’s a Cuban-born drug dealer who becomes a stand-in dad, and Ali’s performance ought to earn him an Oscar nomination. Shown in the photo teaching young Chiron to swim, he may be the screen’s first drug dealer you intuitively trust in a parental role. Ali delivers an extraordinary master class in acting, mingling a street authenticity with a quiet, firm longing to protect this child and affirm his sexuality however he chooses to define it.

The other key influence in Chiron’s life is his childhood pal and teenage sex interest, Kevin (played by Jaden Piner, Jharrd Jerome and, as an adult, Andre Holland). The reunion between the grown Andre and Chiron occurs late in the film—Kevin is a waiter in a Miami diner, Chiron has bulked up and sports diamond earrings and double gold front grills. It’s a new beginning for the two men that brings an ideal closure to Jenkins’ movie.

The director’s screenplay honors its source, In Moonlight Black Boys Look Pale, a short play by Terrell Alvin McCraney. Jenkins told Film Comment magazine that his film “is an ‘art-house movie,’ but it’s also just about home”—indeed, the same Liberty City blocks in Miami that both he and playwright McCraney grew up in. Shooting in Super 16mm, Jenkins’ film radiates tiny moments of grace—Chiron as a boy carrying a kettle of heated water into his bathroom to pour himself a hot bath…Chiron and Kevin as teens holding hands tightly through their first sexual embrace…Jenkins’ use of the handshake between black men known as dapping (Jenkins acknowledges it as a spiritual transference)…Andre’s keenly amused observation to Chiron that “you’ve never said more than three words together.”

Indeed, there are numerous huge closeups of Chiron in his childhood, his youth and his fully grown maturity in which he stares at the camera, saying nothing—but he’s never a blank canvas. We always sense he’s thinking about something, and Jenkins has built enough lonely mystery into his taxing life that we keep imagining the many things Chiron might be thinking. James Laxton’s unobtrusive cinematography and Nicholas Britell’s softly reassuring compositions all underscore the mature confidence of Jenkins’ vision.

If Nothing But A Man brought cinematic soul to a very young festival in 1964, Moonlight has a cinematic heart that ought to reach way beyond Lincoln Center’s silver screens in 2016.

Moonlight shows Sunday, Oct. 2nd at 6:15 pm in Alice Tully Hall and Monday, Oct. 3rd at 9 pm at the Walter Reade Theater.

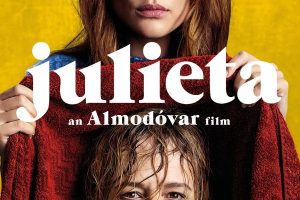

Julieta

(Pedro Almodovar. Spain. 2016. 99 minutes)

Reviewing Stories We Tell in 2013, your critic went out on a precarious literary limb and pronounced director Sarah Polley “the Alice Munro of Canadian filmmakers.” Part of this accolade was a tribute to Polley’s debut feature, Away From Her (2007), a faithful rendering of Munro’s Alzheimer tale, The Bear Came Over the Mountain, with Julie Christie’s indelible performance. Part was a tribute to Polley’s artfully constructed cine-memoir, Stories We Tell, an exploration into her parents’ lives. Both features honored Michiko Kakatani’s description of Alice Munro as “the creator of pictures that possess the pain and immediacy of life, and the clean, hard radiance of art.”

Now it’s time to widen the Munro circle of celebrated directors, announcing without hesitation that Almodovar’s 20th feature, Julieta, has just made him the Alice Munro of Spanish filmmakers. Julieta grows out of three sequential stories in Munro’s 2004 collection, Runaways; all three stories appeared first in New Yorker.

They follow the title character, first played by Emma Suarez in middle-age, living in Madrid, backward in time to her 20s (where she’s played by Adriana Ugarte), when she fell in love with a fisherman (Daniel Grao) with whom she had a daughter. They lived an idyllic life in Redes, a Galacian fishing village, for over a decade. Though her companion dies in a boating accident, we watch their adoring and affectionate pre-teen lovingly raised by Julieta, until at 18 the girl suddenly walks out of her mother’s life, never to return. Why? Almadovar’s movie cross-cuts past and present, meditating on the mother’s ecstasies and sudden losses.

One of Alice Munro’s lifelong gifts as a writer of short fiction has been her keen ability to shift focus within a brief narrative, setting aside one character to follow another, often for no apparent reason. Short story writers rarely attempt this—the effect on the reader can be disconcerting—and Almadovar doesn’t attempt much of this sleight-of-hand in Julieta. Instead his goal is accomplishing something equally difficult as a filmmaker: he makes you believe Ms. Suarez and Ms. Ugarte really are the same woman, even though there’s an age difference of nearly a quarter century and the two actresses don’t resemble each other that closely.

As in Moonlight, we’re watching actors of different ages play one character at different life stages, just as we’ve done throughout our movie-going lives. The technique is timeless. But the execution here is flawless—the fit between Suarez and Ugarte is almost as believable as watching Ellar Coltrane growing from age six to age 18 in two hours and 46 minutes, before your astonished eyes, in Linklater’s Boyhood. And that’s as good as it gets.

Almadovar also elects to play what could be a slow, dreamy narrative as an urgent, knife-edge drama with a tinge of mystery. The picture initially will remind you of Brian De Palma’s sleek Passion, with its taut cutting of two female corporate execs sexually drawn to each other in glassy skyscrapers and posh conference rooms. Only here, we’re watching the same woman finding and then losing nearly all the initial promises, pleasures and satisfactions of her life in a host of settings, from the sweaty intimacies of a train compartment to the cobbled streets of Redes in northern Spain. (It’s no accident two of Munro’s other collections are titled Too Much Happiness and Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage.)

Almodovar is fond of inserting visual devices—Julieta’s heart beating under a screen-filling image of red fabric… the recurring image of a small sculptured naked man she often holds… and an astonishing moment through a train window of a huge stag pursuing the train on which Julieta will first encounter the fisherman. None of this vivid imagery is in Munro’s three stories, though a brief encounter with an older man on the train who shortly commits suicide is. Take his suicide as an omen.

Munro includes another much longer dialogue between Julieta and the Redes minister, in which Julieta declares her atheism and angrily tells the clergyman “we don’t believe in God’s grace—it’s not like denying (my daughter) nourishment, it’s refusing to bring her up on lies.” Almodovar ignores this meeting, though it’s the core of the three stories in which faith (or lack of faith) seem to determine fate. He lets the reason for the daughter’s disappearance from a spiritual retreat center come from its severe director, and it’s a sudden surprise Almodovar hasn’t prepared us for.

As a filmmaker Almodovar stays more earthbound than, say, Ingmar Bergman, though there’s a moment when he echoes Bergman’s classic freeze in Persona where he splices half of Liv Ullman’s face against half of Bibi Anderson’s face, suggesting they’re the same woman. It’s suggested mischievously in the poster image in which you see the younger Julieta drying her older counterpart’s hair—an illusion as they are the same woman.

Almodovar, like De Palma, has always been drenched in his love of movies. He’s mused that the naked statue fondled by Julieta “is the same proportion as the blond prisoner in King Kong’s hands.” In Almadovar’s world, Julieta may have felt that possessive of her own daughter, like Joan Crawford was of Ann Blythe in Mildred Pierce until the daughter betrays the mother. At the end a soundtrack voice tells us “If you leave, my world is going to end, a world where only you exist. Don’t leave. I don’t want you to leave, because if you leave that’s the very moment I’ll die.” That’s how we experience Julieta both at the start, and the finish, of this unsettling film: full of Munro’s “pain and immediacy of life, and the clean, hard radiance of art.”

Julieta shows Friday, Oct. 7th at 6 pm and Saturday, Oct. 8th at 12:30 pm in Alice Tully Hall.

Graduation

(Cristian Mungiu. Romania. 2016. 127 minutes)

It may not sound like a ringing endorsement, but Graduation is another thrilling chapter in the New Romanian Cinema’s endless dissections of that country’s broken institutions.

Like plow horses that keep tilling the same barren, impoverished fields, the new crop of Romanian directors—Mungiu, Cristi Puiu, Corneliu Porumboiu, Andrei Gruzsniczki, among many—keep dramatizing the locked-down decades of life in the grip of Nicolai Ceausescu’s regime, and its bitter aftertaste following the dictator’s trial and execution in 1989. The bottom-line of all their films is direct and unwavering— “never again”—even as Romania struggles today to unload its ancient, corruption-ridden infrastructures and create a workable government—plus a culture that can attract visitors to more than its geriatric spas and Dracula legends.

(Full disclosure: this writer criss-crossed Transylvania in the summer of ’75 on assignment with The Monster Times fanzine, out of which came a trade bestseller, A Night In Transylvania, a cross-cultural survey of the historical Vlad Dracula and the literary and filmic vampires. In 1975, Puiu, Mungiu and Porumboiu were ages eight, seven and two. Life was a lot easier for a visiting American journalist than for these kids and their parents.)

Their collective cinematic work sets the stage for everything that happens in Graduation. The Death of Mr. Lazarescu (Puiu) follows a dying 62-year-old alcoholic through Bucharest’s primitive hospital system. Police, Adjective (Porumboiu) offers a portrait of a young police detective shadowing and reluctantly arresting a teenage drug user, only to be unbraided by a precinct captain who’s the most law-and-order authoritarian since Vlad the Impaler, the 15th century ruler who partly inspired Bram Stoker’s Dracula and certainly influenced Ceausescu. Quod Erat Demonstrandum trails a glum Securitate agent as he starts a surveillance (phone tap and apartment search) on a math teacher in a city where the lights don’t work at night and people wait in lines for hours to buy bananas.

Mungiu’s Four Months, Three Weeks and Two Days explores a pregnant college student and her girlfriend’s dicey journey to find a back room technician who’ll abort the pregnancy without killing the patient. The same director’s Beyond the Hills takes on Romania’s powerful Orthodox Church, basing its story on an exorcism at a remote Moldavian monastery that resulted in a young woman’s death.

And here, in Graduation, the enormously accomplished Mungiu centers his attention on a Cluj physician whose daughter, a high school senior, has just been assaulted and is in poor shape to try and pass the exams that will determine whether she gets into Cambridge, which has provisionally accepted her. The father’s solution? Elbow his way into the controlling bureaucracy and fix it so at least the kid escapes their drab urban apartment and a life without hope. It’s a premise—if not a plan—almost any parent can identify with.

Mungiu quickly erects the frustrations and barriers facing Dr. Aldea (Adrian Titeni, a steady and inventive actor who’s always thinking ahead of the roadblocks). His daughter Eliza (Maria Dragus) is shaken but also taken with a local motorcycle boy who may have been involved in her assault. His wife Magda (Lia Bughar) is a dazed, chain-smoking library assistant, who senses or knows her husband is having a long-term affair with a young teacher, Sandra (Malina Manovici) at Eliza’s school. Sandra has her own agenda, which is marrying the doctor and engineering herself and her own kid into the better life he’s promised her It’s a pitch-perfect ensemble cast and Mungiu doesn’t dawdle like some other Romanian directors who’ve discovered “slow cinema” and can make your feel like you’re watching paint dry.

The surgeon goes to work on one of his patients whose liver has failed and who’s a deputy mayor in the government, as well as the exam committee president plus the chief exam inspector who’ll monitor Eliza’s tests. The father’s goal with all three men is getting one top grade for Eliza that will cancel her poor test results the day after she was set upon near her schoolyard. His key strategy is moving his important patient up the list for a liver transplant. But we learn the doctor and his wife left Romania through the worst of Ceausescu’s dictatorship and didn’t return until 1991, another bad decision— it’s also a decision a lot of higher-up loyalists have noted. The surgeon’s apartment complex on the outskirts of Cluj (Romania’s second largest city) is a bleak high-rise where the dogs never stop barking and a rock gets tossed through their front window.

Thus begins the cat-and-mouse centerpiece scenes not only of Graduation but most of these superior Romanian exercises: how to beat the system or at least game it enough to survive in it. Eliza is a bright girl but still has a moral compass, and resists her father pulling strings— there’s a cutting scene between them that’s heartbreaking in its candor and desperation as the flummoxed doctor explains to a stone-faced daughter (who’s considering not going to college at all) how life in Romania works and doesn’t work in 2015.

Mungiu has spoken of “Romania’s elite students,” and how proud teachers are of this elite. “But they often leave to continue their studies abroad, and only a tiny number come back,” states the director. “This is a problem that leads to local corruption. If you are in a country where freedom came just 25 years ago, a lot of things are not yet settled. People need to understand you need more ethical solutions to set examples for your children.”

He’s right, and whether Graduation provides them is yours to discover.

Graduation shows Tuesday, Oct. 11th at 6 pm and Wednesday, Oct. 12th at 9 pm in Alice Tully Hall.

I Had Nowhere To Go

(Douglas Gordon. Germany. 2016. 97 min.)

Ooh, this doc is cause for celebration. The director is Scottish artist Douglas Gordon, whose 1993 installation slowed Hitchcock’s Psycho to a 24-hour marathon viewing experience. Gordon’s subject is Jonas Mekas, the 93-year-old filmer (not filmmaker, please) and co-founder of Manhattan’s Anthology Film Archives, started in 1970, which presents over one thousand programs each year. What mischief could these two mavericks come up with?

Gordon’s concept was shrewd and daring: Mekas had produced so many images since 1949 when he migrated from Lithuania to Brooklyn and started shooting a diary of his daily life, that Gordon felt he didn’t need any more. The director was betting if Mekas simply voice-overed adapted readings from his memoir covering the war years he spent with his late brother Adolfas in Nazi labor and displaced persons camps, plus his early years in Manhattan and Brooklyn, he had the essence of a compelling film.

But here was Gordon’s biggest leap of faith: The director believed all this could work against a virtually blank screen, for 97 minutes. If the memories and anecdotes were vivid enough. If Mekas was not only a superlative reader but a crackerjack storyteller. And if—here’s yet another creative challenge—Gordon could create a sound and music collage that would hold a spectator glued to one’s seat.

In short, what Gordon set out to create was a diary film/cine memoir you’d attend to not as you’d view an installation—where your eye could wander at will—but a movie in which your eyes would stay riveted on a big screen on which, most of the time, absolutely nothing is happening.

Gordon, who’s 50, isn’t quite old enough to remember how millions of people worldwide once listened to radio by gathering around it and staring at it. But he must have sensed that the concept might be viable if all the elements—actor, script, sound and music—were working together like gangbusters. And are they ever working in I Had Nowhere To Go.

Gordon, who’s 50, isn’t quite old enough to remember how millions of people worldwide once listened to radio by gathering around it and staring at it. But he must have sensed that the concept might be viable if all the elements—actor, script, sound and music—were working together like gangbusters. And are they ever working in I Had Nowhere To Go.

The actor. Mekas has a lilting, soothing Lithuanian accent. Like Werner Herzog, his voice is instantly recognizable. They’re both precisionists who speak in whole sentences—sometimes in whole paragraphs. You don’t need to see Mekas to realize he’s speaking what Herzog calls “the ecstatic truth.”

The script. Gordon and Ninon Liotet (who’s also the editor) adapted Mekas’ 13-chapter memoir (1991, Black Thistle Press). The events shift back and forth from the war years in the camps, to Mekas’ first years of freedom in New York City. They’re “fragments of a life,” ranging from daily hunger, fear and despair, to the exhilaration of discovering that “everything fits so perfectly in this city.”

The anecdotes are vivid: A Russian officer rips the film from Mekas’ only still camera. We hear about (or see glimpses of) potatoes being peeled, nights sleeping on barracks’ floors, days waiting for Red Cross shipments. Mekas tells how he disguised himself as a woman and walked out of one village. Border guards search Jonas and Adolfas’ meager belongings and find little besides books.

In Manhattan, Mekas gets legitimate work and begins filming with his first Bolex camera. He goes to Blood of a Poet at the Fifth Avenue Cinema, visits the Gotham Book Mart on West 47th ‘where wise men fish,’ pays a quarter to watch a stripper on 42nd Street caught in “endless and terrifying boredom.” The 20th century is no longer the villain in his life. He can sing Lithuanian folk tunes, accompanying himself on accordion. He is a poet, an artist. This is a man who still walks into America’s foremost institution of independent film preservation and restoration today, wearing his original World War II jacket.

Sound and music. The centerpiece scene of I Had Nowhere To Go is an aerial bombardment lasting nearly ten minutes. You’re staring at an empty screen, cringing under a constant barrage of bombs, mortars, cannons and other artillery. The production sound designer and re-recording mixer was Frank Kruse, who created the eerie/ominous effects track for Laura Poitras’ Oscar-winning Citizenfour. Dave Powers and Paul Oberle contributed the original sound elements, which are gripping in their hair-raising simplicity.

This is also the first motion picture edit using Dolby Atmos technology, which integrates 128 audio tracks plus metadata. For this listener, the experience was even more realistic (and scary) than historian Richard Schickel’s meticulous restoration of battlefield combat in the soundtrack of Sam Fuller’s Big Red One, shown by the Film Society of Lincoln Center in 2004.

Gordon’s documentary is a premiere attraction in this fest’s newly coined “Explorers” series. It really belongs in “Projections,” which is another coy rebranding of what for years New York Film Festivals called “Views From the Avant- Garde.” In terms of both originality and accessibility, I Had Nowhere To Go stands shoulder-to-shoulder with Phillip Warnell’s Ming of Harlem: Twenty One Storeys In The Air (2014 NYFF). In that documentary Warnell first explored how a Harlem resident kept a 450-pound Bengal-Siberian tiger (Ming) and a 7-foot Caiman alligator (Al) housed in his one-bedroom apartment for years. When NYPD finally hauled “Dr. Doolittle” and his brood away, Warnell built an exact replica of the apartment in a London zoo, installed a replacement tiger and alligator, and started filming. The new Ming and Al, amazingly, immediately took to their new living area, kitchen, bathtub, bed and sleeping platforms.

You don’t see stuff like this at the multiplex.

I Had Nowhere To Go shows Thursday, Oct. 13th, at 6 pm at the Walter Reade, and Friday, Oct. 14th at 9:15 pm at the Bruno Walter Auditorium.

Can’t Take My Eyes Off You and Personal Shopper

(Johannes Kizler, Nik Sentenza; Germany; 2016; 12 min.) and (Olivier Assayas. France. 2016. 105 min.), respectively.

The two gold standard pre-festival haunted house movies of this century are Ti West’s House of the Devil (2009) and Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook (2014). West has the edge because Devil spends most of its running time fastened on a teenage girl (Jocelin Donahue) edging her way around and through a creaking mansion and up its stairs toward an attic seething with evil. That creepshow was such a tribute to 20th century things-that-go-bump-in-the-night that Magnolia released a VHS promo version in clamshell box for horror fans who’ve kept their VCRs in good working order.

Assayas’ Personal Shopper stays similarly focused on Kristen Stewart, playing a salaried assistant to a high-profile socialite. Kristen has a weak heart and spends the first reel wandering through the gloomy empty house where her 27-year-old twin brother suffered a fatal stroke and is now visibly ghosting the premises. As she goes about her work spending a small fortune updating her boss’ designer wardrobe, the only people we see her engaging in real conversation with are her faraway boyfriend who’s a computer whiz, her dead brother’s girlfriend, and her married employer’s grumpy lover. She tries speaking to her ghosted brother to no avail; aside from the occasional thump and bump, he’s a silent apparition.

But then someone starts texting the brittle, mournful young sophisticate. Who could be Kristen’s cyber-stalker? We’ve seem only three possibilities—well, make that four if you count the deceased brother, who becomes a shadow presence and demonstrates the ability to grasp solid objects like a glass. One of the three people closest to Kristen ends up horribly murdered, and we see her ghostly brother has been flanking her employer’s lover, too. No more info here— Assayas has a lot of tricky misdirection up his talented sleeve.

Kizler and Sentenza have the premiere short in NYFF’s “Genre Stories” category of “new horror, thriller, sci-fi, pitch-black comedy, twisted noir and fantasy.” Think of their tingling 12 minutes as “Little Personal Shopper” or even “Little House of the Devil.” The camera is following a slimly attractive mom (Julie Bremermann) at night around the handsome home she shares with her teen daughter (Maja-Celiné Probst). Right away we think we notice something moving in the downstairs shadows.

When the sassy teen daughter comes home, she’s told her father has canceled their weekend plans. They argue. As mom walks off to the kitchen and pours a glass of wine, the daughter sulks upstairs to the bathroom. She discovers “DADDY HATES YOU” lipsticked on the mirror. The girl runs downstairs—the wine bottle is in shards on the kitchen floor. Slowly, inch by inch, the camera reveals her mother twitching on a chair trying to draw her final breaths, soaked with blood just like Kristen’s boss. The terrified teen bolts up to her bedroom and locks herself in—then turns with a scream to see what we can’t.

Can’t Take My Eyes Off You is vintage horror, done with a modern pulp sensibility and assurance that Assayas might admire. Johannes Kizler attended the Filmakademie Baden-Wurttemberg and was on the shortlist of Young Director Award at Cannes. His brother and co-director Nik Sentenza is a writer/producer/editor/composer, making his sixth short.

Their film plays within the rules of the genre, which are greatly broadened by Assayas using social media as his centerpiece platform. Both approaches work, but you may find yourself dismissing the possibility of a ghost texting. On the other hand, remind yourself that any spirit who can carry around (and drop) a glass tumbler has fingers that could operate a mobile device.

Can’t Take My Eyes Off You shows Saturday, Oct. 1 at 9:15 pm and Monday, Oct. 3 at 9:30 pm at Bruno Walter Auditorium. Personal Shopper shows Friday, Oct. 7 at 9 pm and Saturday, Oct. 8 at 3 pm at Alice Tully Hall.

My Journey Through French Cinema

(Bertrand Tavernier. France. 2016. 192 min.)

The fest is a treasure trove of French culture from the past and present. On the main slate, there’s Paul Verhoeven’s Elle and Mia Hansen-Love’s Things To Come (both starring Isabelle Huppert and neither shown at this writing). NYFF’s “Explorations” section gives a victory lap to Jean-Pierre Leaud enacting The Death of Louis XIV—a ravishingly moribund closure in which Mr. Leaud’s weak smile (as he pets his dogs at bedside) still reveals traces of Antoine Doinel who he played at 14 in The 400 Blows in 1959, followed by four more films in Truffaut’s Doinel cycle.

“Retrospectives” and “Revivals,” two other fest offshoots, showcase Renoir’s La Marseillaise (1938), Bresson’s Angels of Sin (1943) and L’argent (1983), Becker’s Antoine and Antoinette (1947), Melville’s Les Enfants Terribles (1950), Duvivier’s Panique (1947) and Deadlier Than the Male (1956), Rivette’s shorts (1949-52) and Tavernier’s own Safe Conduct (2002). All of these flank Bertrand Tavernier’s three-hour opus of his cinematic growth through four decades of watching movies, starting as a “war child of the Popular Front” in 1944 Lyon.

It’s a how-they-did-it assembly of clips similar in structure to Thom Andersen and Noel Burch’s massive 1995 doc, Red Hollywood (reviewed here two years ago), their thrilling examination of how left-wing screenwriters influenced four decades of American films. Tavernier (The French Minister, A Sunday in the Country, Round Midnight, Coup de Torchon) gives us an intimate, detailed tour through the French movies and actors we’ve grown up with—it’s the one film at this NYFF in which one could sense an audience literally leaning in to screen images, with murmurs and sighs of awe and recognition wafting through the Walter Reade auditorium.

The director’s diary starts with a 20-minute salute to the neglected work of Jacques Becker, whose “formal and visual command perfectly understood American filmmakers like Howard Hawks.” Tavernier’s first defining movie experience was a chase scene in Becker’s 1942 proto-noir Dernier Atout which he likely viewed at the Far West theater (a name that tickles Quentin Tarantino). Becker had worked as assistant director to Jean Renoir and learned to “constantly follow the heartbeats” of rising stars like Simone Signoret and Louis Jourdan in the romance Casque d’Or. He consistently “maintained a crisp, lean pace through organic and simple plots, with the camera at eye level, ” including the jaunty Antoine and Antoinette. Becker was, in the best sense, a journeyman director.

Tavernier builds the next half hour around Jean Renoir, who taught him the wisdom of immediately staying to view a seminal film a second time. From studying La Grande Illusion, A Day in the Country and Rules of the Game, Tavernier learned basics: overlapping dialogue; plotting foreground and background action through depth-of-focus; following actors like Simone Simon and Jean Gabin with lateral movements instead of cuts; getting casts comfortable with tyrannical cinematographers; and maneuvering through a studio system in rough formation. This is where we begin to realize we’re being treated to a half-day course not just in film aesthetics, but in the precise vocabulary of how to make movies that audiences will watch.

Jean Gabin, arguably France’s most revered actor of the first half of the 20th century, became Tavernier’s “passport to understanding the Popular Front,” the left wing social Democrat movement of the mid-30s. Gabin’s rugged romantic heroes of that pre-war era—styled like James Cagney’s protagonists unfolding in America—transitioned into a slew of ’50s and ’60s dramas in which Gabin matures (white hair, stooped gait, a fear of heart attacks) into a measured, authoritative actor with the heft and assurance of Spencer Tracy. These later scenes chosen by Tavernier demonstrate how Gabin earned the reputation of “directing the director,” rewriting scenes to suit his pacing and physical abilities, and insisting on a familiar crew. They show him easily dominating charismatic newcomers like Brigitte Bardot and Jean Paul Belmondo. Like Tracy, Gabin discovered how to do more by doing less.

Tavernier recognizes another all-but-forgotten director, Marcel Carne, whose “dignified, unpretentious and placid” work concealed a workaholic helmer who “yielded on nothing” and served his scripts with integrity. Carne often used the actress known as Arletty (Children of Paradise, Hotel du Nord), a glamorous former fashion model who partnered Carne’s favorite actor, Jacques Brel. As a director, Carne was a loner who doted on 32mm lenses and was skilled in working in impossibly tight sets.

Two music composers given special attention are Maurice Jaubert—“who best understood mise en scene of all French composers”—and Joseph Kosma. Jaubert (1900-1940), in films like L’Atalante, Le Jour se Leve, and Port of Shadows, sensed that a solo instrument, like an accordion, saxophone, or flute, “could find the heart of a film…its climate, its pulse” in ways no Hollywood composers, who rarely were co-equals with their directors, could achieve. Miklos Rozsa and Henry Mancini were among the first U.S. composers to change that with their uses of an eerie theramin in The Lost Weekend, Spellbound and Experiment in Terror. Oscar-winner Trent Reznor (The Social Network) has tucked unsettling electronic scores into Gone Girl and Laura Poitras’ Citizenfour. But back in the ’70s, it took Francois Truffaut to re-record and partially preserve Jaubert’s memorable scores, incorporating that composer’s music in his own later films.

Joseph Kosma, “who was Jewish, Communist and underground,” also innovated unforgettable solo and classical ensemble scores into La Grande Illusion, La Bête Humaine and Children of Paradise. Kosma and Jaurbert paved the way for the solo instruments nearly every cinephile recognizes today, like the zither in The Third Man and Miles Davis’ trumpet solo accompanying Jeanne Moreau through nighttime Parisian streets in Elevator to the Gallows. (Kosma also composed the jazz ballad “Les Feuilles Mortes” sung by Yves Montand in Les Portes de la Nuit [1946] and later adapted with English lyrics as “Autumn Leaves” by Johnny Mercer, becoming the title song in Joan Crawford’s 1956 movie of the same name.)

The crime drama pleases Tavernier, though not what he criticizes as the “limp and unexciting” world of film noir. His favorite bent hero is Lemmy Caution and his “brisk, brittle, straightforward violence.” Played by the stone-faced Eddie Constantine in a string of thrillers (Cet Homme Est Dangereux, Ca Va Barder, Alphaville), Lemmy is closer to Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer, a brawler with far less pedigree and manners than American gumshoes Sam Spade and Phillip Marlowe, both acted by Humphrey Bogart. Lemmy is quick with a quip (“Speak English. They hate subtitles.”) and “doesn’t always have a grip on the situation.” Tavernier’s tribute clips— directed by Jean Sacha, the blacklisted John Berry and Jean-Luc Godard— played to audiences clearly taken by the Gaumont press translations of U.S. crime classics like Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon and Chandler’s The Big Sleep. The one American noir Tavernier pays tribute to in this enlightening section is Delmer Daves’ Dark Passage.

At this point, Tavernier shifts to an exploratory session roaming over a varied canvas of individual films, directors, activities and jobs held in the industry. The tonality of this section is not unlike what NYFF Chair Kent Jones wrote in his introduction to the fest’s 82-page four-color program: “It’s not a matter of us being right or wrong about anything. It all comes down to this: these are the films that we love, and we want to share them with you.”

Tavernier speaks of his delight watching Robert Mitchum dubbed into Vietnamese in Macao. He acquaints himself with Henri Langlois’ 50,000 movies at the Cinematheque Francaise. He acquires prints of Edgar Ullmer’s Babes in Baghdad and Sam Fuller’s I Shot Jesse James, Tavernier spins through scenes from Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Shoot the Piano Player. An actor chewing a toothpick reminds him of Sterling Hayden in Warner Brothers’ Crime Wave. He champions the fringe director Edmond Greville’s Menaces with Charles Vanel, Noose with Carol Landis, Port du Désir with Gabin. He pronounces Godard’s Pierrot Le Fou with its CinemaScope vistas of Brigitte Bardot swirling across a gorgeous color screen “simply sublime.”

During the ’50s and ’60s we note the ascendency of Belmondo and Alain Delon in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Leon Morin, Priest; Le Doulos (a Tarantino favorite); Le Samourai; and Le Cercle Rouge. Melville tells Tavernier, who’s working as his assistant, that he’s inadequate but would make a good press agent. So Tavernier finds a job as a press agent and gets fired in days. Some of this is hilarious.

The final section is devoted to films of Claude Sautet, to whom (along with Becker) this work is dedicated. Sautet, also a much-requested script doctor (Franju’s Eyes Without a Face) helmed everything from gangster thrillers (Classe Tous Risques) to poetic and moving romantic dramas like The Things of Life (1970) starring a radiant Romy Schneider (directed by Sautet in five pictures) and the inimitable Michel Piccoli. Tavernier’s doc concludes in 1970, near the beginning of his own career, to be explored in full in the future.

My Journey Through French Cinema is assured a long life on at least one Manhattan screen. The doc’s distributor is Cohen Media Group, which has acquired and is renovating the four-screen Quad Cinema on West 13th Street…where one can imagine it playing forever.

My Journey Through French Cinema had its first New York showings Oct. 1 and 2 in Lincoln Center.

The Lost City of Z

(James Gray. USA. 2016. 140 min.)

At a Q&A preceding the world premiere of his rousing jungle adventure, writer/director James Gray was asked his opinion of the new ways movies are being distributed. Many people present were aware the fest’s Opening Night selection, Ava DuVernay’s documentary on black incarceration, 13th, is being distributed by Netflix, while Gray’s Closing Night selection carries the new Amazon Studios banner. (Amazon’s lengthy animated logo, the first element up on the screen, erects a whole mall with a big multiplex marquee “playing” the Amazon Studios name.)

Polished and amiable, Gray said he’d bought books to toilet paper through Amazon without a hitch, and that their North American plans for his movie seem fine. But then he reflected on the loss of this kind of epic that whole families flocked to in the early 20th century. The viewer had observed studios like MGM and directors like Alexander Korda once gave pride-of-place to motion pictures like Four Feathers, King Solomon’s Mines and Trader Horn. “If we hadn’t shot on 35mm, our film would have looked very different in digital,” Gray said. (Darius Khondji, who lensed The Immigrant by Gray, Amour and Magic in the Moonlight, is a 35mm devotee.)

Gray took another question on how closely his film was meant to resemble Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Werner Herzog’s harrowing 1972 biopic on the obsessed Spanish soldier, played by Klaus Kinski, and his failed attempts to find the fabled lost city of El Dorado. Gray acknowledged Herzog’s world class artistry but made clear that his rendering of explorer Percy Fawcett’s repeated explorations to find El Dorado from 1906 to 1925 was totally different from Herzog’s Aguirre. The director was right, as a comparative summary of his movie with Fawcett’s published diaries (Exploration Fawcett: Journey to the Lost City of Z, Overlook Press, 2010) and David Grann’s first class journalistic reportage (The Lost City of Z, Doubleday, 2009) will reveal:

The real life Fawcett. Born in 1867, Fawcett became a British lieutenant in the Royal Artillery in a time when “much of the discovery of the world was based on failure—on tactical errors and pipe dreams—rather than success.”

He married Nina Paterson, an unwaveringly supportive spouse and also an avowed feminist, in 1901. Fawcett was essentially a surveyor and cartographer who would map much of South America, receiving a gold metal from the Royal Geographical Society, one of the continuing funders of his expeditions (along with the Museum of the American Indian).

Tall and imposing in his gabardine breeches, leather boots, stetson and silk scarf, Fawcett waded into the primeval wilderness between Brazil and Bolivia—“a jungle canopy so dark it appeared almost black,” swarming with mosquitoes, leeches, sauba ants, ticks, biting gnats, millipedes, parasitic worms, piranhas and vampire bats. His primary instruments were sextant, chronometer and glycerin compass. He faced yellow fever, malaria and hostile tribes who would either kill intruders (by arrows or blow darts) and eat them, or imprison captives for life. But like Aguirre, Fawcett plunged ahead into this “permanent midnight” world filled with “death and suffering worthy of Joseph Conrad.”

He never faltered. In the two decades covering his journeys, Fawcett grew steadily convinced “the forests contain traces of a lost civilization of a most unsuspected and surprising character.” His research pointed to a possible 1753 first sighting of a vibrant city he simply named Z.

In 1910 Fawcett visited the more docile Guarayos tribe after singing “Soldiers of the Queen,” waving a handkerchief in friendship, and offering gifts. He absorbed the Guarayos’ culture, acquired a knowledge of herbal medicines and native ways of hunting, and through oral histories from the nearly extinct Botocudo Indians learned the history of a 16th century “golden man.” This was El Dorado, a fabulist ruler who was said to cover himself with gold dust. Fawcett knew countless explorations before his had ended in death, but he vowed to find El Dorado/Z and its buried treasures before anyone else.

Journalist David Grann reveals the extent of Fawcett’s obsession when he examines the archeologist’s actual diaries. He discovers that Fawcett’s reports to his sponsoring institutions may have been deliberately falsified—that the longitude/latitude coordinates he recorded were a blind to throw competitors off the most likely location, which Fawcett believed “was in a jungle surrounding Xingu River in the Brazilian Mato Grosso.” Another of Grann’s significant findings is that Fawcett’s gold signet ring eventually turned up in a shop in Cuiaba, Mato Grosso’s capital, “bathed in blood.”

Fawcett’s in-and-out excursions only agitated his frustrations. One millionaire competitor was using a 45’ boat, a $6,000 wireless telegraphy set, and a 160 mph hydroplane equipped with aerial cameras and bombs. Percy, Nina and their three children were living back in England “in gentile poverty,” and Fawcett began selling family heirlooms plus half his military pension to raise more expedition funds. He also promoted himself from lieutenant colonel to colonel, to increase his attractiveness to investors.

While his wife and children briefly moved to Los Angeles, Fawcett was finally able to secure funding through selling story rights to the North American Newspaper Alliance, and from a $4,500 donation from John D. Rockefeller, Jr. At one point Colonel T.E. Lawrence (the legendary Lawrence of Arabia) offered to join Fawcett, but the explorer passed, instead recruiting his 21-year-old son, Jack, and a friend, as his assistants on what would become a final exploration in 1924. They were heading toward the Brazilian state of Para, planning to exit near the mouth of the Amazon river. Fawcett carried a stone idol given to him as a gift by H. Rider Haggard, the author of King Solomon’s Mines and She.

Grann makes it to the village that was Fawcett’s stepping-off point into the unknown, meeting the last aging native who remembers, as a child, seeing Fawcett. “What is it that these white people did?” the woman wonders. “Why is it so important for their tribe to find them?” In his final chapter, David Grann discovers the most likely truths of Z from an archaeologist, Michael Heckenberger, who has lived many years in the Kuikuro settlement with the peaceable Xingunos tribe, who may indeed be the last living links to a highly advanced ancient civilization.

Heckenberger’s book, The Ecology of Power (Routledge, 2004) spells out what Grann sees for himself: massive moats, circular plazas, domed houses and palisades walls, all built in carefully concentric circles and littered with the broken pottery that Fawcett first pieced together. The Xingunos king gently tells Grann that in all likelihood Fawcett’s expedition met its doom at the hands of the neighboring, violent Kalapalos tribe close to Z that the intrepid explorer had finally found—too late.

James Gray’s film. Gray’s Lost City of Z is light years removed from Herzog’s Aguirre, which drilled down into the excruciating and palpable suffering that infuses Klaus Kinski’s pursuit of El Dorado. In that stark drama, everyone on the Kinski expedition dies by starvation or arrows, including Aguirre’s teenage daughter, who the crazed soldier boasts he will marry “and with her I will found the purest dynasty the world has ever known!” Fans of the five grueling movies Herzog endured with Kinski will never forget Aguirre’s stunning conclusion, with cameras circling Kinski alone on a raft in some Peruvian river while 400 monkeys leap about at his feet. In the Herzog/Kinski world, the misery index starts at 10 and keeps climbing. No way is this Gray’s vision.

What Gray has opted for, instead, is a colorful tale filmed in the Columbian rainforest that’s never less than absorbing. The director cross-cuts jungle treks with family life and a long sequence illustrating Fawcett’s heroic exploits in the trenches of France during World War I, leading his artillery brigade into combat in a ferocious scene that recalls the charge led by Kirk Douglas in Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory. Gray wants us to fully embrace his Fawcett (Charlie Hunnam) as intelligent and feeling, a proudly attentive husband and father when he’s not in the wilds or fighting Germans. Hunnam replaced Benedict Cumberbatch in the lead role, who may have replaced exec producer Brad Pitt.

The scenes that work best are those replicating the less abrasive entries in Fawcett’s diaries, like the explorer singing and gifting his way into a tribe’s trust. Hunnam is commanding and handsome without being overbearing, a modern-day composite of Stewart Granger (in King Solomon’s Mines), Clark Gable (in Mogambo), and Charlton Heston (in The Naked Jungle). There are also echoes of Gary Cooper’s stoic performance in Garden of Evil (1947), partly filmed in Acapulco jungles and one of 12 films directed by Henry Hathaway which were all shown in this festival.

Fawcett is also something of what a ’30s pulp magazine like Adventure once called a “bent hero”—flawed but honorable— in a movie-movie that’s in the tradition of Jules Verne’s Lost World or even the Hell-Job stories invented by L. Ron Hubbard during his 15 years as a penny-a-word pulpster.

For variety Gray offers up a sumptuous scene in a wilderness opera house (not unlike Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo) or a thunderous opening chase of British army troops on horseback pursuing a stag (that’s a cautionary preview of how Fawcett’s expeditions will have to learn how to live off the land). One lesson Gray has taken from Herzog’s epic is not to abandon an audience in a jungle for 94 minutes, let alone 140.

The supporting cast makes up a commendable if conventional ensemble: Fawcett’s surveying partner and aide de camp (Robert Pattinson); his son (Tom Holland); a wealthy but ill-prepared associate (Angus Macfadyen); plus the usual nay-sayers in the scientific community who regard

indigenous Amazon tribes at best as “noble savages” even as these stuffed shirts proclaim Fawcett “the David Livingstone of the Amazon.”

As Nina, Sienna Miller makes a more lasting impression. She combines an imperious, aristocratic bearing with a will that constantly bends to and cheerleads her husband’s unceasing expeditions. Nina never accepted that her husband and son were in all probability murdered in the jungle. She believed to her grave that Percy had found Z. Watching Miller work, one unconsciously compares her acting with that of Cynthia Nixon playing the poet Emily Dickinson in the festival’s A Quiet Passion, directed by Terence Davies. Nixon captures Dickinson’s cold and bitter loneliness with impeccable craft, but her chilly and condescending manner keeps you at a distance; Miller draws you in with an independence that easily co-exists with her life as Fawcett’s primary advocate. She knows how to forage for herself and her children.

Gray had a choice at the end of his film whether to include David Grann’s remarkable findings a decade ago— that the descendants of Z ’s mound builders exist and today are being visited by leading archeologists. As noted in this critique, Grann also offers persuasive evidence that Jack and Percy (and one of Jack’s close friends) lost their lives to a savage tribe that the 58-year-old father had successfully avoided for two decades. Gray chose not to go there. It’s a debatable artistic choice and a missed opportunity—The Lost City of Z might have transcended its Saturday matinee roots as a superior popcorn movie, into a learning document that girls and boys in middle school science classes could study forever.

Gray’s call reminds us of that closing scene in John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, when Jimmy Stewart, knowing how Lee Marvin’s evil villain really died, takes the true story to the local newspaper editor, played by Carlton Young, who turns it down:

Stewart: You’re not going to run the story, Mr. Scott?

Young: No, sir. This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

This 54th NYFF’s Closing Night drama opts to print the legend. You could say the fest’s curators have struck an ideal balance, because Ms. DuVernay’s Opening Night documentary, 13th, “prints the facts” without a moment’s hesitation. It’s a striking contrast between reel life and real life, and Netflix and Amazon Studios have their work cut out for them.

The Lost City of Z had its world premiere October 15 in Lincoln Center.

This concludes critic’s choices.

Watch for Brokaw’s next choices in the 26th New York Jewish Film Festival, January 11-24.