Tribeca 2017: Critic’s Choices – Documentaries

Kurt Brokaw picks Clive Davis, Frank Serpico, and Hedy Lamarr’s Bombshell as his favorite docs

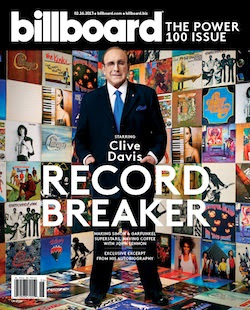

Clive Davis: The Soundtrack of Our Lives, Chris Perkel, 2017, USA, 123 min.

In the late 1960s and early 70s, RCA Records’ main competition in the music business was Columbia Records and 35-year-old Clive Davis.

While your critic’s advertising and promotion unit was knocking out advertising and promotion campaigns for RCA headliners like Jefferson Airplane, The Guess Who, and The Kinks, Davis was eating our lunch, scooping up what would become superstars and monster acts like Janis Joplin, Chicago, Aerosmith, Moby Grape, Santana, and Blood, Sweat and Tears. RCA managed to snag a couple of real comers including David Bowie, Lou Reed, and Nina Simone, but our cross-platform mainstays at the time were Elvis Presley and John Denver. Columbia and Clive topped them all, signing Simon and Garfunkel, Bruce Springsteen, Miles Davis, Dionne Warwick, and Billy Joel.

As Chris Perkel’s jam-packed and exhaustively comprehensive doc proves over and over, Davis had four big edges over Atlantic, Warners, RCA, Epic, Elektra, and every other major label in pursuit of contemporary acts: First, he knew radio better than most because he’d grown up listening to “Make Believe Ballroom” and the real giants of post-World War II pop music—Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, and Johnny Mathis. He understood their music and how Mitch Miller and Andy Williams had seized easy-listening, easy-viewing audiences coast-to-coast.

Second, he realized faster than his competition that radio—next to television, America’s most powerful mass medium—was a series of platforms (pop, rock, folk, r&b, jazz, country, gospel, classical, spoken word) and that artists could transition from one to another, moving up and down the radio band and capturing different listening audiences with the right mix of songs.

Third, Davis never forgot that a record company’s #1 daily challenge was pulling the right single out of every album, because radio play on singles sold not just millions of LP recordings, but the newly discovered innovation of music on stereo 8 cartridge tapes. And finally, Davis never got too chummy with the men and women he vaulted to stardom—he was the consummate, all-business professional, and he turned a blind eye to the mountains of substance abuse and cross-addiction that were endemic to the industry.

Davis surely knew of “The 27 Club” that claimed rock idols Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Brian Jones and Janis Joplin at age 27 between 1967 and 1971 (and later Alan Wilson of Canned Heat, Ron McKernan of The Grateful Dead, Kristen Pfaff of Hole, Kurt Cobain, and Amy Winehouse, also at 27). But only Joplin and McKernan were on his labels.

Davis refused Janis’ offer to sleep with him with a thanks-but-no-thanks. Bob Weir called him “the one suit” he and the Dead could trust. Davis went to Monterey fest dressed in Nantucket best, but he was captivated by the Summer of Love and its alternative lifestyles. He formed a life-time routine of hauling home piles of acetates and cassette recordings, and watching 3/4” VHS tapes of every new voice and sound, studying it all, forever seeking that magic “spark of originality.” He’d learned due diligence in law school, but he applied that discipline to music school.

Like Brian De Palma in his own engrossing documentary, Davis is his own best narrator and talking head, and he stays excellent company over two hours. His legal training gives him a precisionist’s mastery of language, and he’s never less than collegial when he modestly admits he’s always learning-while-earning. At 85, Davis is both an American icon as well as a quintessential New Yorker, and he gives you the full nine yards on how some clingy song from what Perkel calls “the playlist of hits forever stuck in your head” came to sell 20 million copies 40 years ago.

It’s hard not to believe and trust his genius, even when he’s explaining how he was fired from Columbia in ’73 and narrowly escaped a payola scandal, losing his law license (which he later earned back). He founded Arista Records, a formidable profit center for Barry Manilow, The Outlaws, Patti Smith, and Melissa Manchester, and later J Records, which became the big time launch pad for Alicia Keys, Luther Vandross, and Kelly Clarkson, plus Bad Boy Records, home base for Sean “Puffy” Combs and the Notorious B.I.G.

Later Davis found himself ousted from his post as CEO of RCA Music group (which included Arista, J Records and the Bartelsmann Music Group), “for making too much money.” These days he’s chief creative officer for Sony Music Entertainment, where his current projects include sourcing the right material for artists from Jennifer Hudson all the way back to Johnny Mathis.

Davis builds credibility through Perkel’s performance clips and artist interviews—the director also served as editor of this lavish tribute doc. They knit together a pyramid of music superstars of the second half of the 20th century, all paying effusive tributes. Paul Simon marvels at how Davis insisted the breakout Simon & Garfunkel single had to be “Bridge Over Troubled Water” and not “Cecilia.” Kenny G shakes his head in wonder that Davis, a Jew, would persuade Kenny, a Jew, to record a Christmas album. (And then write personal letters to radio station disc jockeys urging them to play it.) Springsteen looks awed by the memory of Davis sending him back to pen a vocal (“Blinded by the Light”) that would become the highlight of his first album.

The charts-toppers are backed by a wide bench of industry leaders (Ahmet Ertegun, Berry Gordy, Lou Adler) as well as erudite rock journalists like Anthony DeCurtis, the Rolling Stone editor with the Ph.D, who co-authored The Soundtrack of My Life four years ago with Davis. (That book first disclosed Davis’ bisexuality, which he addresses quite openly on camera.) The veteran producer David Foster recalls a blistering, profanity-laced argument with Davis over “I Will Always Love You” from Whitney Houston’s movie, The Bodyguard, which Davis wanted left in its original rough version, while Foster insisted on layering and enriching. (Davis released the original.)

Despite occasional artistic differences, everyone’s in the same applauding choir. It’s obvious why Manhattan’s most inclusive film fest chose Perkel’s movie for its gala opening night in Radio City Music Hall, with Davis surrounded by more of his stellar artists (Aretha Franklin, Jennifer Hudson. Carly Simon, Earth, Wind & Fire) in performance.

The last section of Perkel’s doc is the longest, and encompasses Ms. Houston’s meteoric career. Davis was her mentor at Arista starting in 1985 singing backup behind her mom at Manhattan’s Sweet Waters club, and the 19-year-old would become his pride and joy as well as a phenomenal success (eight platinum albums and 55 million records sold in America) until her death in a Beverly Hills hotel bathroom in 2012.

It’s a heart wrenching conclusion: Davis’ decision to keep artists’ relations at a purely professional level masked his ability to see Houston being derailed by hard drugs. When he attempts an intercession through a poignant, painful letter to her that Davis reads on camera, our hearts sink because we realize it’s too little, too late.

Perkins’ doc is primarily though not entirely a look-back, filled with images of honest-to-goodness record albums with all their compelling graphics and commanding cover images. Today, real record stores like Mercer Street Books and Records and Westsider still dot Manhattan, and vinyl has expanded to unexpected quarters— both the Strand bookstore in Greenwich Village and The Last Bookstore in downtown LA maintain healthy LP sections.

Thank Clive Davis. Happily and hopefully, “the man with the golden ears” is insuring that the past is mere prelude to the present and the future.

Frank Serpico, Antonino D’Ambrosio, 2017, USA, 96 min.

The money shot happens 44 minutes in, on the night of February 3, 1971. The NYPD detective has driven from the 80th precinct to an apartment building on Driggs Avenue in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, to make a narcotics buy and then arrest. He’s packing his 38 Special and has two cops behind him as backup. When the third floor apartment door opens, he wedges his head in but the criminals inside slam the door, trapping him. Frank manages to turn enough to yell for help. When he turns back, he’s shot in the face.

As we learned much earlier in this gritty, finely tuned look back at a New York City filled with 70s disarray, misery and corruption, the bullet, a 22, was removed in surgery but lead fragments lodged in Serpico’s carotid artery. One fragment remains in his jaw. Another fragment fell out of his left ear some years ago. He’s deaf in that ear from the blast and will always walk with a limp.

The sequence is frightening—almost devastating—to watch, because while D’Ambrosio doesn’t restage the shooting, he doesn’t have to. He intercuts it with Al Pacino acting Frank in Sidney Lumet’s riveting 1973 movie, Serpico. So we get twice the paralyzing anxiety and angst. We feel Serpico experiencing a “cold, eerie feeling” that night even before leaving the precinct, later scoping out the building roof and thinking he should shut down the operation and turn back, finally proceeding and minutes later laying face up on the hallway floor in a pool of blood, thinking the back of his head has been blown away.

Where was his backup? Serpico still isn’t sure. A 911 call was made by a building resident, not a police officer. The response was made by police as a 10-10, not the 10-13 that signals an officer needs help and may be down. Much later, Frank tells us that one of the men who eventually picked him up said “if I’d known it was Serpico, I’d have left him there to bleed to death.”

This is the price one pays as NYPD’s most legendary whistle blowing narcotics detective, though Frank dislikes that term and describes himself as a “lamp lighter.” D’Ambrosio’s investigation is on Serpico’s side starting with his roots as a rookie cop in 1959, through 1972 as a narcotics detective (he sounded feisty as ever at age 81 in front of a Tribeca fest audience). With one important exception, the talking heads chosen by writer/producer/director D’Ambrosio show no reluctance in their support of Serpico’s approach to crime fighting. Many are retired NYPD officers and administrators.

The exception—the one voice of authority who was on the shooting scene and was part of Serpico’s narcotics squad, and sits for his interview right across from Serpico— is Arthur Cesare. He’s a burly, well-spoken retired narcotics cop. Cesare was in a car outside the building. The viewer is watching and listening very carefully, weighing who’s a trustworthy narrator and who’s not. Cesare looks and sounds like he’s playing with a full deck:

“When the captain said you were joining our team, I said ‘Why us? I heard he was a rat, he was squealing on cops taking money.’” Cesare looks at Serpico. “Nobody trusted you. But as a cop, you have to trust the people you’re working with. (When I saw you shot), I thought, what the hell am I doing here? You’re looking up at me and I’m wiping the blood away, and you’re joking ‘what are you tryin’ to do, smother me?’”

Frank presses Cesare on why the call went in as a 10-10 (‘possible crime’) and not a 10-13 (‘assist patrolman’). Cesare doesn’t have an answer and he sits reflecting. And then he admits what may be this troubling doc’s most terrible truth: “After 20 years, you just get used to it.”

D’Ambrosio’s point-of-view never downplays why Serpico was disliked as a bearded undercover cop who lived in Greenwich Village and affected elaborate disguises as he integrated himself into the lives of drug dealers. “I was everything from a doctor to a derelict,” explains Frank, “and my life depended on how well I played those roles.” Two years after he testified at the Knapp Commission calling out department corruption at the highest levels, Pacino played him in the Lumet movie— forever branding Serpico as the maverick outcast. (When the detective loudly protested the director shooting a violent scene that Frank said never happened on his watch, Lumet barred him from the set.) No wonder authors and journalists couldn’t write enough about such a bent hero.

Today Serpico lives quietly upstate in Columbia County, in a woodsy home with Hudson River views. He points out his ‘healing place’ with a wind chime that he’s remodeled with a built-in nightstick. The very first scene in the movie could have played just as well had it been the last scene —it’s Frank examining his face in a mirror, preparing for his closeup. Talk about a heart of darkness.

Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story, Alexandra Dean, 2017, USA, 90 min.

Hedy was an inventor and scientist trapped in the body and mindset of a Hollywood star. Manhattan audiences discovered that eight years ago when Elyse Singer wrote and staged an off-off-Broadway play called “Frequency Hopping.” That was the name given to simplify the work of a jamming device invented in 1940 to prevent the Nazis’ torpedo guidance systems from striking American ships during World War II. The initial concept was worked out on a piano roll programming with 80 frequencies, and came to be known as “spread spectrum,” one of the foundation pieces of cellular phone technology—and, by extension, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and GPS. “Frequency hopping” has become a more defining and memorable descriptive and branding device.

How this marvel came to be invented is better than any movie Hedy ever starred in. It involved her collaboration with George Antheil (1900-1959), an avant-garde musician and composer whose seminal 1924 “Ballet Mécanique” used multiple pianos, xylophones, bass drums and even three airplane propellers. Antheil is more easily remembered for his later scores for films noir like In a Lonely Place and Knock On Any Door.

In 1940 Antheil was a bon vivant writing for Esquire, and got acquainted with Hedy, then the tall, throaty beauty who swam nude in the 1933 Ecstasy and would star opposite Victor Mature in the DeMille spectacle, Samson and Delilah. Hedy was an Austrian emigre whose first German husband knew weaponry and aircraft, and her own inquiring mind and knowledge synced with Antheil’s pioneering musical instincts. Frequency hopping became their patented, support-the-war-effort contribution.

It’s worth mentioning that Ms. Singer staged this extravagant piece of theater using eight synchronized Yamaha Disklavier player pianos on surrounding platforms (along with suspended bass drums and gongs), dialing up a 25-piece robotic orchestra. Singer also dazzled audiences with the Musion Eyeliner video holographic projection system, which is translucent and raked to accept film clips and even virtual life-size talking actors in 3-D, from projectors mounted below a thrust stage.

Hedy would have understood and loved all these bells and whistles. “Films have a certain place in a certain time period, but technology is forever,” she observed. In real life, neither the actress nor her composer ever received a cent for their invention. Hedy plowed through a string of high and low screen melodramas, from Algiers to The Strange Woman to The Female Animal, shed six husbands, and pooh-poohed her movie work with lines like “Any girl can be glamorous. All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.” On screen, she might be considered a more exotic, Europeanized version of Joan Bennett. Hedy was finally recognized by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which honored her in 1997, at age 83, three years before her passing.

Alexandra Dean’s Bombshell adroitly and concisely fuses the movie world Lamarr performed in with her mostly unknown scientific expertise and experiments. (A front page story in Stars and Stripes was one of the few publications of the era that recognized her work.) Dean assembles the key invention with helpful animation and lucid narration—it’s simplified but never dumbed-down.

Dean makes good use of Hedy on audio tapes, discovered by Forbes writer Fleming Meeks years after he interviewed her in 1990, as well as the requisite array of film experts (Jeanine Basinger, Peter Bogdonovich), actors (Diane Kruger, Mel Brooks) and assorted industry figures (Michael Tilson Thomas, Turner Classic Movies’ late and beloved host, Robert Osborne). Dean nails the huge ambivalence of her subject perfectly when she says “That thing you do that’s pure you—that sometimes is how you make your mark, not all this ambition and striving.”

Bombshell may be the first feature length documentary to play as well in a middle school science classroom today as it will decades from now on TCM—a unique way to win both ends of the viewing spectrum without any hopping between channels.

This concludes Documentary critic’s choices. Read Brokaw’s reviews

on Features and Shorts.

Regions: New York City