New Documentary on Historic “Rumble in the Jungle” Boxing Match

History and International Studies Professor and Filmmaker Gnimbin Ouattara Talks to The Independent's Editor about His Recent Documentary, Ali, mbomayé

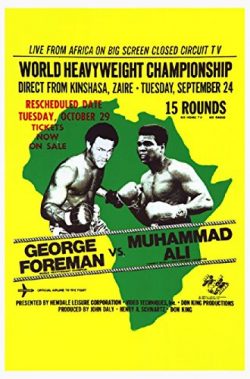

Dr. Gnimbin A. Ouattara is a Fulbright scholar from Côte d’Ivoire. He received his PhD in African Political History in 2007 from Georgia State University and is currently Associate Professor of History and International Studies at Brenau University in Gainesville, Georgia. His work compares Cherokee and West African “civilizing projects” within a framework of the nineteenth-century Atlantic. He is also a 2010 graduate of the Georgia State University Film School, where he specialized in historical documentary. Gnimbin’s newest film, Ali, mbomayé, is about the 1974 boxing event between George Foreman and Muhammed Ali in Kinshasa, Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo). The Independent’s editor reached out to Gnimbin to discuss the politics, production, and artistry behind Ali, mbomayé.

Tell us a bit about your background. How did you come to work on this project?

As you know, I came to the United States in 2001 on a Fulbright scholarship. I was interested in how Africans fit into the political history of the United States. My research took a detour as I discovered more of Indigenous history. I ended up with a dissertation in 2007 titled Africans, Cherokees, and the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions: An Unusual Story of Redemption.

This work was an effort to document, for Africans, the trajectory of the ideology of the so-called civilizing missions of the nineteenth century. Many political observers of the continent, indeed, underestimate the continuing effect of this ideology on modern African education, started, one may recall, by these missions. Feeling that writing a book would not quickly deliver my research to my African people, I decided to go back to school to pursue a Master’s degree in Film and Video. I was already appointed to my first faculty position, but I thought that going back to school again was a good price to pay in order to engage effectively with my people, who still privilege orality as their mode of communication.

Since graduating from Georgia State University, I have been forced to live in the United States as an asylee. Still, I did not give up on my dream of harnessing the power of film. I produced a few films for Brenau University, where I also teach. I wanted to test a filmmaking perspective called “community-based media.” This was introduced to me in film school by my instructor, Nik Vollmer. In a sense, Ali, mbomayé is my first post-graduate film, in line with the goal that sent me to film school.

What inspired the subject of this particular film?

The idea for Ali, mbomayé came to me immediately when I learned of Muhammad Ali’s passing. I was deeply saddened by the news and wanted to mourn the champ with everyone. My way of doing that was to answer his call in When We Were Kings that black people should use film to help Africans and African-Americans learn about each other.

With Ali, mbomayé, I wanted to revisit the George Foreman vs. Muhammad Ali heavyweight title fight from an African perspective. Many Americans know about this 1975 bout in Zaire. The fight has been called the most famous heavyweight boxing match of all times. Many others learned about it thanks the Academy-Award winning documentary, When We Were Kings (1996). But the significance of this fight for Africans has not been thoroughly explored—not by Americans or Africans themselves. Worse still, the American memory of the fight dominates. And yet, this memory is not good for Africans. In 1974, fight promoters advertised the fight to the American public as “Rumble in the Jungle,” thereby turning Zaire into a jungle and erasing its people at best. The landmark documentary, When We Were Kings, released 22 years later unfortunately, reinforced this same rhetoric. It similarly subjected Zaire to the Western colonial gaze and offered it for the colonizer’s gossip. White commentators in the documentary, for example, visitors for a day in Africa, in a strange resemblance to the nineteenth-century missionary, are heard interpreting for the American viewer what this fight meant for Africans and Africans-Americans.

The African, therefore, must ask, how did the American colonial curiosity for the exotic jungle obstruct the cultural view of Africans in 1974? How did Africans experience their interactions with African-Americans in their own words? Can the Zaire people that flocked to the stadium to watch the match speak? Can the Africans who were glued to their small TV sets at home speak?

Wow! This is very heady material, Gnimbin. And, of course, you had to think about the practical matters of filmmaking too. Can you tell us about the roles you assumed in this project?

I was the writer, director, cinematographer, and editor of Ali, mbomayé. I filmed it with the assistance of a friend, Eric Kotcha, who drove with me to Louisville, KY. Sokofaly, LLC produced it. The African actors include Alain Kouadio, Eric Kotcha, Caroline Okou, Mitzi Okou, and Dominique Zahou. I am grateful to the American participants as well: Austin Render, Mollie Hanrahan, Tara Hornbeck, Rahman Ali, George Bochetto, and Jane Wagner, who graciously availed themselves during the filming in Louisville, Kentucky.

Say more about the technical, stylistic, or rhetorical choices you’ve made with this film? What were you trying to achieve aesthetically or in other ways?

Stylistically, this documentary was conceived as an African courtesy visit to Muhammad Ali. In my view, Ali visited Zaire in 1974 as an African, and it was fitting that we return the favor, as it is done in an African village. The other stylistic choice was an effort to replicate the mood in which Ali visited the continent: friendly, funny, playful, and yet full of meaning. The cultural significance of this moment, indeed, was not lost on Ali despite his antics. Nor was it lost on the throngs of Zaire people who chanted “Ali, mbomayé” or surrounded Foreman.

Therefore, my technical choice was to shoot the film as a cultural promenade in Ali’s hometown of Louisville, KY, just as Ali did when he ran in the streets of Kinshasa. Simplicity and spontaneity were important to achieving this goal, so I settled on a Canon HF G20, a camera that was light enough to be hand-held on a bicycle but also offered a great film look suitable for this documentary.

The rhetorical tool of choice for this film was African orality. African traditional storytelling techniques in the village heavily relied on entertainment (what Europeans may call antics) to punctuate the story. Our ancestors told these stories by moonlight or fireside, paused and sang, or sometimes danced before pursuing the narration without ever losing the thread or the didactic punch. This documentary adopted this rhetorical technique as one that was more suitable to a film about Ali. To the extent that Ali’s antics were quintessentially African, a conscientious effort was also made not to use narration, as it is customary to see in Western documentaries, and instead tell the story in an African way that would have been recognized by Ali and the Africans in the streets of Kinshasa in 1974.

The humor and playfulness of the film is palpable, indeed, despite its weighty concerns.

Ali Bomayé mobilizes the childhood memory of four Africans in telling the story of the famous 1974 fight “Rumble in the Jungle.” Can you discuss why you chose this way into your subject matter? Why create the frame of memory and why these four individuals?

Yes, this is how I conceived of the film. I selected three men and one woman to reflect the gender balance in the stadium of Kinshasa or in front of the small TV sets in African homes that watched the match in 1974. I also sought people from each region of Ivory Coast, people from the north (Caroline Okou,), from the south (Eric Kotcha), from the east (Alain Kouadio), and from the west (Dominique Zahou) who did not know each other during the fight in 1974 but who are now friends.

Many Africans living in the United States today, just like these four Ivorians, were children on October 30, 1974 when Muhammad Ali and George Foreman visited them in Africa for the famous “Rumble in the Jungle.” Today, these Africans are adults visiting Ali and Foreman’s country. Most of them have settled here and have had their own experiences of America, including their own interactions with African-Americans.

While this documentary could have been produced before Ali’s death, his passing and the worldwide pouring of love represented an excellent opportunity for these Africans to revisit the fight and articulate its cultural significance for them at the time and today. In that sense, memory was the driving force behind this film, as it helped defy time and unite Africans across the Atlantic on their own terms.

This film certainly engages the intersection between sports and politics, especially its global scale. Can you say more about the political nature of Muhammad Ali’s legendary talent, career, and persona? What is Ali’s significance, in your mind, to the Diasporic identity?

Muhammad Ali is known in the United States for his political stances such as the rejection of the draft to Vietnam, which cost him his title as world heavyweight champion. There is also his famous throwing of his 1960 Olympic Gold medal in the Ohio River to protest the Jim Crow laws that allowed a segregated restaurant in his native Louisville to deny him service. But for Africans, his arrival on the continent was not political. Certainly Zaire president Mobutu Sese Seko paid $10 million to bring the fight to his country. Still, Africans did not see the fight as the move of a “dictator” to feed his own cult of personality.

If, indeed, this fight was intended as the poison of a dictator that Western commentators identified, George Foreman vs. Muhammad Ali turned out to be a lotus flower for Africans—and for African-Americans as well. It produced an unusual opportunity for Africans to discover on their own terms African-Americans, whom, many learned for the first time, were the descendants of their brothers and sisters violently abducted in the Atlantic slave trade.

The cultural significance of this reunion was not lost on African-Americans either, especially Ali. In the colorful language that was his, he said: “I am gonna fight for the prestige, not for me, but …[for] Black people who don’t know no knowledge of themselves or no future….” This fight also helped him awaken to a mentoring role in which he would use film to uplift African-Americans: “I could help a lot of people [by being here in Africa], I can show’em films. I can take this documentary, I can take movies and help uplift my people in Louisville, KY [and other places]….” He then proceeded to proudly outline the cultural benefit of his presence in Africa: “I can go through Tennessee, Florida, and Mississippi and show them little Black Africans in them countries who did not know this was their country…[sic]” At these words, in a rare serious tone, Ali turned to Africans in the room and said, “…they are your brothers…they never knew you was over here. And you don’t know much about them [sic] (see When We Were Kings).”

After this brilliant diagnostic of the state of cultural vacuum between Africans on the continent and in the diaspora, Ali assigned himself a transatlantic mission, which he insisted, God had blessed him with through boxing, so he could “help gather all these [Black] people to show them films [that they haven’t seen].” Ali, mbomayé fits in this vision of Ali’s to use film to bridge the gap between Africans and African-Americans and to foster cultural unity between them.

How did you get this project off the ground? Can you discuss the pre-production phase of your work?

I first came to the idea of this film, as I said earlier, right after I learnt of Muhammad Ali’s passing. Beside my interest in paying tribute to him, I also remembered one frustrating aspect of the documentary When We Were Kings. The film, for example, opened with a voodoolike image of an African woman. The woman is iconic South African singer and freedom fighter Miriam Makeba, and I wondered why she allowed, if she did, her image to be used in this manner.

This image eerily punctuated the entire film and represented, what a white journalist, George Plimpton, said he was “very interested in,” people called “féticheurs (witches or soothsayers).” In Western Africa, he said, almost everyone had one. You would go to the witch doctor like you would go to a dentist in America, he explained. Muhammad Ali, he claimed, had been to President Mobutu’s “féticheur” who supposedly said, “a woman with trembling hands would somehow get to Foreman—a succubus.” That impressed him enormously, Plimpton concluded.

Leon Gast, the director of When We Were Kings was probably also very impressed by this exotic succubus story. For not only was the succubus used to punctuate the film, her imaginary and sinister performance was made to introduce the stadium where the boxing match took place, as if to suggest that the match was rigged or under the spell of this succubus—a cinematic maneuver, I suppose, in line with the original advertisement campaign of “rumble in the jungle.”

Having studied Christian missionaries to Western Africa, and being aware of the harmful myths that they spread about African indigenous systems of knowledge, I decided to answer Ali’s call to make my own film that would uplift my people, showing them aspects of this fight that they could not see in Leon Gast’s When We Were Kings—the euphoric cultural reunion between Africans and African-Americans.

Indeed, many people think that Africans chanted “Ali, mbomayé” just for Ali, but the truth is that they also chanted “Foreman, mbomayé” for Foreman. It’s just that Foreman did not embrace it, preferring to focus on relishing his return to Africa, as he explained himself: “When I am walking down the street, the kids follow me screaming, ‘George Foreman, Bomayu [mbomayé].’ I don’t think that is so nice to me. I’d like it if they had anything to say about me, they can say, ‘George Foreman loves Africa,’ ‘George Foreman loves being here,’ not ‘George Foreman, kill him,’ I don’t like that.”

Thus, although Ali and Foreman’s voices were amply echoed in When We Were Kings, the framing of the film as an exotic tale eroded the cultural impact of these voices. This is what I explained to the board of Sokofaly, LLC to secure funding for the film, as I also insisted that Ali’s passing was the new opportunity to tell the true story of the euphoric cultural reunion between Africans and African-Americans.

Funds in hand, I recruited a friend to go to Louisville, KY in imitation of the twosome visit of Ali and Foreman to Africa. The script was also conceived to replicate the mood in which Ali encountered Africans. The goal was to set this mood as the model for future encounters between Africa and diaspora—an encounter through laughter, dance, and celebration of the newly found brotherhood.

I then rented a car and my friend and I drove from Atlanta, GA to Louisville, KY on Saturday June 11, 2016, the day after Ali’s funeral. We spent the night there and toured Ali’s birth home and city the next day, Sunday June 12. On our return to Atlanta, I gathered four Ivorians on the weekend that followed (Saturday June 19, 2016) to reproduce the mood in which Africans had watched the fight between Ali and Foreman on TV sets on October 30, 1974.

The result is what you can see in this film, a joyful story of brotherly reunion between Africans and Ali in the reverse, intended to teach Africans and African-Americans about each other, a story punctuated by laughter, dance, and celebration instead of a succubus or white humor. This effort to appropriate the fight for Africans also led me to alter the usual spelling of the chant “Ali, bomayé.” From an African perspective, according to my Lingala consultant Anna N’Koukoun, “Ali, mbomayé” should be spelled with an “m” to reflect the pronunciation in Zaire Lingala language; hence, the titling of my documentary as “Ali, mbomayé.”

What were some specific challenges you faced in creating the film, and what were the ways you were able to work around these?

The main challenge was the structure of the film. Minimally scripted, it was conceived as a tour of Ali’s birth home in which interactions would be spontaneous to mirror Ali’s interactions with Africans in 1974. For this reason, I made no prior arrangements with any officials in Louisville, KY to replicate the mindset of Ali who made no such prior arrangements himself before he left for the Zaire that Don King and others had arranged for him.

This was a big risk because we could have arrived in Louisville and not known where to start, since contrary to Ali, we did not have any tour guides. Fortunately, when we arrived at the Muhammad Ali Center, we benefited from the guidance of Louisville Bicycle Tours, a company of three wonderful people who had dedicated their passion for the bicycle to honoring Ali—you may recall that Ali started boxing because someone had stolen his red bike. They immediately became enthusiastic participants in the film as soon as I explained to them what we had come from Africa to do in Louisville.

We were also lucky to meet Mr. George Bochetto, the founder of Muhammad Ali’s childhood home, right outside the home as he gave instructions to street vendors. He graciously accepted to introduce himself on film and share his vision behind developing this “archive.” As one can see in the film, we met with Ali’s younger brother, Rahman Ali, who ingratiated us with more than an unforgettable photo. This is how we got around a traditionally scripted and narrated documentary and managed to produce what I have called Afrimentary—a documentary telling stories in the tradition of African orality.

What was your approach to working with cast and crew on this film?

There were two types of cast in this film. One was in a sit-down interview and another was composed of strangers interviewed in the street. But the approach in both cases was similar because spontaneity was the goal. I wanted to reproduce the model of human relations in Africa. Africa is a warm place, and interactions tend to be warm and enthusiastic as well. This probably explains why Ali easily connected to Africans and his personality was easily appreciated in Africa. Africans admire warmth. Since I went into this film assuming that there is an Africa in all of us, I was pleasantly surprised that this approach worked in Louisville, KY. People waved, cheered, or shouted pleasantries to me in Ali’s neighborhood when they saw me wearing a suit on a bicycle, as I tried to replicate Ali’s antics in Zaire.

How have you developed an audience for Ali mbomayé?

My target audience is Africans, African-Americans, and Africans in the diaspora at large. I also hope that viewers outside these groups will acquire the film to gain a fresh perspective on the cultural relations between Africans and African-Americans. These two groups are at their best when they remain in touch with their African soul or character. Ali established this cultural precedent in 1974 between Africans and African-Americans. He proved that Africans and African-Americans can drum, dance, or laugh together as one people without looking to a Western cultural translator for the model of their interactions. This is one powerful way he showed people of African descent to become leaders of their own lives, produce their own knowledge, and tell their own stories even through a European medium like film.

What are your plans moving forward, for this film or for another project?

I intend this documentary for the classroom. I hope that many high schools and colleges in the U.S. and Africa will use the film to educate students about Ali’s culturally significant visit to Africa in 1974. This visit outlined a new model for healthy relations between Africa and its diaspora. I hope to have a French version (French subtitles) for such schools in Francophone Africa, especially in Zaire and Côte d’Ivoire. The film is now streaming on Amazon and YouTube and at www.alimbomaye.com. Check it out!

As far as future projects are concerned, I am interested in producing films on the interaction between Africa and its diaspora from an African perspective. I am currently looking for funding to tell the story of the interaction of Africans and W.E.B. DuBois who is currently buried in Ghana. Another story that is dear to my heart is to tell the story of how the transatlantic slave trade started—from an African perspective. This story has not been told, especially in film.

Regions: Louisville, Zaire