New Horizons of Virtual Reality: Exploring Utopia Through the Evolution of Second Life

The Independent's Editor Speaks with Filmmaker Annie Berman about her Film Utopia 1.0

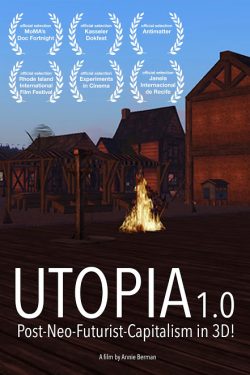

Annie Berman is a media artist living and working in New York City. Her background in photography and psychology inspires work about visual culture, virtual realities, and the changing media landscape. Her films, videos, performances, and installations have shown internationally in galleries, festivals, universities, and conferences including the Museum of Modern Art’s Doc Fortnight, Rooftop Films, Galerie Patrick Ebensperger Berlin, Kassel Hauptbahnhof, and the Rome Independent Film Festival where she was awarded the Best Experimental Film Prize. Named one of Independent Magazine’s ten filmmakers to watch in 2016, her credits include Utopia 1.0: Post-Neo-Futurist-Capitalism in 3D!, Utopia 1.0 in VR, Street Views, and Of Birds and Boundaries. Her work has received support from The Rockefeller Brothers Foundation, UnionDocs, The Puffin Foundation, Wave Farm, The Leonard Bernstein Festival of the Arts, The Center for Independent Documentary, and Signal Culture. She is a member of the Brooklyn Filmmakers Collective, and earned her MFA in Integrated Media Arts from Hunter College.

Recently, Annie spoke with The Independent’s editor about her newest VR project—an exploration of the possibilities and limitations of virtual reality through the aftermath of Second Life.

Welcome back to The Independent. What was your goal with Utopia 1.0: Post-Neo-Futurist-Capitalism in 3D!?

I suppose it was my own desire for something better—at its heart, Utopia 1.0 is about the challenge of reforming economic and political structures in order to create a better world. I’ve heard it said that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. I set out, with this in mind, to find out the limits of our imagination. What better way than to look back on the once hugely successful online virtual world of Second Life—a place that invited its users (or residents as they prefer to be called) to build “your world, your imagination.” Given this invitation to build a new, I wondered what is was that they created? If we cannot create a better world in this fantasy environment, then how can we ever expect to create a better world in our ‘real’ world?

Is this where VR comes in, as a kind of portal to the fantasy world?

Sure! The question of whether or not we can imagine something better is as much a question for the medium of VR as it is for our sociopolitical landscape. I got my hands on a Google Cardboard before anyone else I knew. I was in Grand Central Station, but as soon as I put these goggles to my head, I was soaring through the clouds. It got me excited thinking about the creative potential of this new medium. But, admittedly, I was completely disenchanted by the industry’s vision for the medium, and by early attempts of filmmakers. So, this project was also in some way a provocation for us to invent entirely new ways of filmmaking, of art making—to abandon all rules developed for the screen.

What drew you to this project?

It’s funny to look back on the germination of this project. Preparing for our conversation, I consulted my original notebook and it turns out that originally, I had wanted to visit a place that I might not otherwise be able to due to travel restrictions or other restraints (perhaps places quarantined with Ebola victims, or contested borders, . . .) and to travel there digitally (building off my previous work, Street Views, where I explore NY’s West Village from within Google maps). But, I happened upon a Harun Farocki show in gallery and it was his Parallels I-IV series that made me scribble down, “consider an archaeology of Second Life?” I had also just read Benjamin Kunkel’s book Utopia or Bust and wanted to use the collapse of Second Life’s economy as a way of understanding the collapse of our own, as it’s always easier to perceive in the other. I felt like our culture had grown fatigued with the subject of Capitalist decline, wanted to move on . . . so I thought I could use Second Life as a means for reexamining the global economic crisis, home foreclosures, bailouts, Occupy Wall Street indirectly. But I knew that I wanted to create something for these new VR headsets, something that would conceptually link the future to our past conceptions of future . . . to see the future through the rearview mirror.

Incredibly interesting and innovative… Can you elaborate on the aesthetic style of the film? What were you trying to achieve?

Some people assume this is an animated film, but it isn’t. The graphics you see on screen, are created entirely by the online community of Second Life. The film was created using screen capture software. To inhabit Second Life, I had to learn to use a gaming mouse to control a virtual camera. It was kind of incredible once I learned to pan, tilt, zoom, push in, fly . . . I could achieve things I wouldn’t have been able to in the real world, without some serious funding. But it was a learning experience. I include awkward moments of the “newbie” learning to navigate. The camera, at first, lagging behind its subjects. I believe it lends an honesty, presence, a degree of being “in the moment” that we’ve come to associate with documentary filmmaking, … with reality. I wanted this virtual world, this virtual reality, to be experienced as a reality… or at least represent two worlds simultaneously—the real and the virtual—or the physical world and the world of ideas. I think this is something inherent in much of my work, now that I think about it—and why I integrate my writing and voice.

Can you elaborate on the narrative structure of the film—as a series of “entries.” What was behind this decision? Is it related at all, in your mind, to the experience of virtual reality?

Oh yes! It happened rather intuitively because I was navigating and taking notes, and so a chronological expedition to an unknown land just felt true to form. I wasn’t consciously thinking about how the journal entries replicated genres of voyages to utopia or expeditions in science fiction to unknown territories. But they do. Thomas More’s Utopia, Adolfo Bioy Casares’s The Inventions of Morel, and Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, for example, all utilize this first person narrative as written in a journal. Like Thomas More, who plays both the role of author and the narrator of the first part of Utopia, I use my own persona to lend more believability to this fiction. It was only later, when reflecting back on related works and influences that I realized this. When More’s Utopia was published, there were readers who actually believed it was a memoir. All of these stories aim to surpass the realm of fantasy and of fiction, and break into the realm of, if not reality, than at least of belief. At the same time, each story continues to point back to the fiction. I found that the more real I could make this space seem, the more effective this piece would be.

But you asked about the entries relation to the experience of virtual reality. Yes, I observed person after person putting on a virtual reality headsets for the first time and instinctively looking down trying to see their hands. Although the technology wasn’t yet there to enable this, there was this expectation by the viewer. I found myself doing the same thing. It’s not an unreasonable expectation from a medium that responds to your head movement, and at times, your body’s movement and gaze. Our virtual reality headsets were designed as a gaming platform, where you are the subject driving the action. Of course, UTOPIA 1.0 is not a game. It is a film. And I am the central figure driving the story. So the narrator, subject, point of view, and fixed sequential entry numbers were also my way of setting the expectation of the kind of experience this would be — a linear narrative. That the viewer could sit back, relax, and enjoy the show.

I should add, the first iteration of this project was simply a film that played on large screens to a fixed audience, but that was only because I didn’t yet know how to make a virtual reality film.. I had hopes from the onset that I could later translate the film for the VR headset, as I wanted people to be able to see the future through the rearview mirror. Yes, even now I find myself returning to McLuhan’s The Medium is the Massage….it remains amazingly relevant.

There is a post-apocalyptic or dystopic quality to the film. Viewers travel with you through sparsely-populated and eerily unchanged “ruins” of an earlier digital experiment. What do you think about the tension between utopia and dystopia? What do you want your film to suggest about either?

Yes. I think this tension between utopia and dystopia has always existed. For me, this film ends on a bit of a hopeful note, but some may disagree. I’m curious to learn what readers think the film suggests about either or both. For me, the film is about our desire for utopia—or our “will to utopia”…as Lewis Mumford would say. For anyone interested in utopias and dystopias, Mumford’s The Story of Utopias is a must read. It became a bit of a guiding text, and provides the guiding quote that opens the film: “[Utopias] exist in the same way north and south exist . . . We may never reach the points of the compass; and no doubt we shall never live in utopia; but without the magnetic needle we should not be able to travel intelligently at all.”

In other words, our future depends on our capacity to imagine utopia, to desire a better world, set our sights on it, chart our course . . . I’d say this collective will has never been stronger, at least in my lifetime, just look at the resistance of movements like Black Lives Matter, Me Too and others. This came after the film, at the time I was thinking more about the Occupy Wall Street Movement, which is why I choose to end there. I do so subtlety; I only name Occupy Wall Street in the credits, but the final character in the film, Marisa Holmes, is speaking about Occupy Wall Street, not Second Life. I chose not to name either so that the film would speak more broadly to a history of the human impulse for utopia. But are there limits to our imagination? Can we rebuild using the master’s tools?

Ah! This leads me to ask you about dimensions. What were you attempting to explore about time and space with this film? There are hilarious moments, often created by technical difficulties (like when you arrive in Detroit as only a head, your body trapped beneath virtual floorboards). How do these comedic sequences figure in themes of time, space, and possibility?

Great question! My being in that virtual world was itself an exercise in space and time. The world of Second Life is constructed as a space. A place, organized geographically as islands on a map. As I navigated this space, I enjoyed discovering the laws of nature that were in place, and especially the moments in which the logic failed, like when I discover an edge, a line in which the world ends and I can’t move beyond it. Here is a world in which my human-looking body can fly, but also bangs into glass windows. Free falling after accidentally stepping off an elevated field, it seems gravity exists. On the one hand, the time/space of Second Life creates an expectation of moving through time and space in a way we are accustomed to. And yet, on the other hand, glitches enable me to, at times, do things like walk through walls and fly through deeper layers of the terrain.

During the process of making this film, I’d take long walks through the park and down by the river. Walking is when many of the ideas come together for me, and I know what I must do when I return to the edit. Sitting on a rock overlooking the Hudson River is where I devoured the text The Story of Utopias. On one such walk, I needed to simply turn off my thoughts about the project, and I plugged into the podcast On Being with Krista Tippett, whose guest just happened to be science writer Margaret Wertheim. Wertheim was talking about physics and our understanding of ourselves and our relation to the world . . . Suddenly I heard her predict that the generation growing up with virtual realities will learn that “reality is not just matter in motion through space,” that reality is more than a spatial system . . . that there are also “psychological or spiritual aspects of our being.” She went on to assert that because of this understanding, the VR generation will reject “pure materialism.” Now I’m no physicist, but this made sense. It intrigued me, inspired me to further investigate Second Life’s laws of physics. In one scene, disappointed with the commercial exploitation of this virtual world, I run to the ends of the earth and attempt to jump off, but the world does not permit this. I find an edge, which brings me back. When still learning to navigate, my avatar falls from a platform in the sky—surprised that walking off a platform causes one to fall through space. “What did you expect would happen,” the other better acquainted avatar asks? On the one hand, there exist physical representations of bodies and landscapes that act and are acted upon, as they would be in the real world, and on the other hand, there are anomalies.

Can we think for a minute about technical challenges outside the film’s story world? How did you work around these? What did you learn about the VR experience in making this film?

I think the biggest challenge was that this was early 2015 . . . being among the “firsts” is really hard because none of the technology is quite there yet, and you must do the early work of piecing it all together. But that’s also one of the greatest rewards—when people put on a VR headset for the first time in their lives, and their very first experience of the medium is your film.

Our job would have been much easier if there were such a thing as screen capture for 360. The question became: How can I translate this film into an experience for the VR headset? I was resolved to do so no matter what, even if it meant watching a flat movie in a headset. The headsets were still so new and, for me, it was more important to link the two ideas conceptually then to create a fully interactive VR experience. But the VR version evolved, fortunately, to become something far more developed. I was selected to participate in a summer Art-a-Hack residency at Thoughtworks offices in NYC, where my project was matched with a creative technologist and another artist/curator with a focus on video games. Together, we experimented with our options and laughed when we realized they weren’t too dissimilar from earlier iterations of interactive films, like the old CD-ROM films that allowed you to choose your own adventure. Ultimately, we all agreed that this piece was best represented as a movie, which was how it was originally conceived of and constructed. So we set out testing platforms, headsets, and durations. We initially settled on the Oculus Rift headset and Unity software, and determined that 8 minutes was the maximum folks could tolerate given eye strain, attention span within the headset, etc. So I created a condensed 8-min version.

Later, thanks to a grant from NYSCA/Wave Farm, I was able to create the final version with the VR Lab at NYU: Mahe Dewan, Javier Molina, and Todd Bryant. Mahe recreated everything within Unreal software for the Samsung Gear VR headset. We added a Q&A with my avatar that follows the screening, using a motion capture suit to make my avatar. We even Skyped in one of the film’s main characters, Marco Manray in Italy, who I’ve still yet to meet in person! I was hoping to release the final version on Google’s Cardboard because I felt it was more accessible to the many DIY container and compatible with more phones, etc., but the team felt we needed more processing power and eye control. I think this remains a large challenge for creating VR works—the limited and isolated delivery choices, and also how rapidly what is created becomes obsolete as people upgrade their phones, etc.

I was blown away by how good things looked in Unreal [the software]: we present the film in a movie theater, but the theater walls and floors transform into ruins, the sea under a starry sky, and the like. I learned that graphics still look a million times better than video in VR. It’s gotten better, but I am still less than enamored by the quality of videos of 360 video in these headsets. You can bring back stunning footage only to render it out to this soft pixelated looking end product.

Can you say more of what you learned making the film? How did you exhibit your work?

We exhibited the prototype at Babycastles Gallery in NYC and had 130 people experience it in one evening. For 99% of them, it was their first time. Actually, I learned a lot from that evening. While Dave Tennent, our talented developer, focused on the software, Lee Tusman, fellow artist and curator, and I focused on the experience, which included the physical space of the gallery. It was important to set the expectation that this was a cinematic experience, not a game, so we sat viewers three at a time (would have been more if we’d had access to more headsets and computers. We were running each headset off its own laptop). Three ushers dressed as avatars seated each viewer, helped them with their headset, and served them popcorn. The popcorn not only signaled this was a cinematic experience, one in which you could sit back and enjoy the show, but also activated the remaining senses—smell, touch, and taste. Also it connected viewers to their body as a physical, material object.

Having been introduced to VR films at new media festivals, I knew that most of the “experience” involves waiting in long lines, something I personally don’t have much patience for. I knew that attendees would spend much of their night waiting in a queue, and I wanted to engage them in the wait. So, we positioned the three audience members in chairs facing outwards. In other words, they were on display. Above them, a screen projected what they were seeing. We created a playlist of the ambient music from the film, piped it into the gallery, and projected slideshows—one about Second Life, another of the history of 3D perception; we exhibited the latter in an old video game console, and displayed some of Marco Manray’s photographs in viewmasters and 3d keychain viewers.

How did you get such an exceptional and multi-dimensional project like Utopia 1.0 off the ground? Can you discuss the pre-production phase of your work?

I just dove right it— getting to work on the parts I knew how to, which was the content, and believing that the rest would follow. At the time, I saw technologists working in the field, but not artists/filmmaker/creators . . . there was such a visible need for content. I relied upon blind optimism, perhaps—the belief that if I built it they would come. “They” being the technologists. Or, if all else failed, that I’d be able to figure it out myself, teach myself.

I began by creating a Second Life account and exploring it, recording everything in the process, not yet knowing what would be useful to me. I don’t really distinguish pre-production from production. It all comes into being by doing. Fumbling through the dark.

I write my impressions as they come. Those thoughts return, deeper and more developed sometimes later—in the kitchen, shower, park. I record my scribbled notes and see how they work with picture. Again, this is a back and forth. In speaking the lines aloud, I inevitably rewrite them.

Did you have a cast or crew on this film? How involved did you become with the actual people behind the avatars appearing in Utopia 1.0?

There was no crew, just me. I was the location scout, virtual camera operator, sound person, writer, narrator, editor. I first expected I’d find my subjects (the cast) by the natural process of navigating this space. But, I realized early that to understand the evolution of Second Life— the degree to which things had changed or disappeared, I’d need someone who knew in its heyday. I thought immediately of Rebecca Nesson. It was from Rebecca that I first learned of Second Life; she’d spoken at conference at Harvard in 2007, about how Second Life was being used as a virtual classroom. I heard her again on a radio show The Moth, a well-produced amateur story-hour, and knew she’d make a dynamic subject. She accepted my invitation to be my guide in Second Life and to revisit, with me, Harvard’s Berkman Island—where she used to teach classes.

An advisor to the film put me in touch with some artists (people who had been active in Second Life) and from there, I was introduced to “Marco Manray.” I couldn’t have invented a better subject: Marco Manray is the avatar of Italian artist Marco Cadioli. We never met in person, only in Second Life. Between 2007 and 2008, Marco took these amazing documentary photographs within Second Life. He exhibited his work in a real gallery and simultaneously in a virtual gallery within Second Life. When Second Life became this huge news story, major media outlets like Reuters hired him to take photos for them or help their journalists. He hadn’t been back to Second Life since. The film captures his reaction to seeing what’s left and remembering what was.

My third and final subject was my colleague Marisa Holmes. When I invited her to join me, I imagined that we’d talk about either her experience or impression living in Detroit (drawing comparisons between Detroit and Second Life), or her involvement creating another kind of parallel society as part of Occupy Wall Street. Marisa did not wish to talk about Detroit. Looking out at the sea, out towards the horizon, she reflected on her experience of Occupy Wall Street with the insight four years brings. I was pleased with how this shared virtual environment created an optimal space for such thoughts, and moved by the tone of our conversation. If you removed the words Occupy Wall Street, many of the sentiments expressed felt interchangeable with those who helped build Second Life. My intent was not to equate Second Life with Occupy Wall Street, but rather to use both as examples of our desires and impulses to create something better.

Since first exhibiting Utopia 1.0, how have you developed an audience for this film?

The film was fortunate to have its NYC premiere at MoMA’s Doc Fortnight. It went on to screen internationally at film festivals and was released this year to the educational market—to students at universities studying media, communications, innovation, design, architecture, urban planning, archaeology, political science, and the humanities.

The VR installation was presented first at ThoughtWorks NYC (in Beta), at BabyCastles Gallery in NYC, and at an exhibition at the Knockdown Center in NYC. It has also shown at conferences such as Codes and Modes in NYC, iDocs in the UK, and most recently at RIXC Art Science Festival in Riga, Latvia.

As mentioned, my goal was to make the VR version accessible to as many as possible for free via Google Cardboard’s more readily accessible DIY platform. However, my developers convinced me that we needed more processing power than Cardboard enabled. The final version was created for Samsung’s Gear VR and is available in Beta until it passes the final hoops and jumps of the Oculus Store (the only way I found to self-distribute the VR version). The most frustrating part is that we no longer have any remaining funding for revisions for the Oculus Store, so it’s currently hanging in limbo, unless one of your readers with such skills wishes to volunteer!

Let’s hope for this! What are your plans moving forward, for this film or for another project?

Technology by nature moves forward—faster and faster each day. Few have the time to look back. But when we do, there is much we can learn. This film feels just as relevant today as when I made it. Just the other day, I read this great long-form essay in The Atlantic telling the story of Second Life then and now, posing similar questions.

It’s exciting to see the film being integrated into some university classrooms in a variety of fields from emerging media at NYU, to Game Studies, Architecture and Urban Planning, and Political Science. I’d love to get it into even more classrooms. The educational DVD is available for purchase at annieberman.net. There, you can also download the free Beta version of the Gear VR version. And, as I mentioned, I’m still hoping to make the VR version more readily available across different platforms, for free.

I was pretty sure this would be my first and last VR piece, but actually, I’m in post-production on a 360 film called Berlin Notebook. One of the strongest elements of VR is this ghostlike feeling, and I had a similar feeling when I visited Berlin….having one foot in the present and the other in the past.