New York Film Festival Sept. 28-Oct.14

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw Salutes His Top Features and Shorts

Her Smell; Alex Ross Perry; USA, 2018; 134 min.

Perry’s full-tilt booze and dope opus more than earns its main slate slot in The Film Society of Lincoln Center’s 56th annual festival, but the fest it deserves to open (cue the red carpet and all-night sober after party) is the Reel Recovery Film Festival and Symposium. That assembly of mostly obscure dramas, docs and shorts is going into its 6th year locally Nov. 2-8 at the Village East, and rapidly establishing beachheads across America. It spotlights ferocious films of alcoholism and addiction as well as—sometimes—the fragile and tentative first seeds of recovery. The Q&As don’t often feature name filmmakers or known actors, but the bold-face name panelists have included New York authors Lawrence Block and Susan Cheever, and the late New York Times journalist David Carr.

Perry’s movie is a classic by-the-book, before-and-after, fall-and-rise of another female rocker. Movies have forever given us a procession of unforgettable actresses playing show biz alkies, potheads, coke heads and junkies—from Susan Hayward as an out-of-control pop songbird in both Smashup: The Story of A Woman and I’ll Cry Tomorrow, Ann Blythe in The Helen Morgan Story, and Kim Novak in Jeanne Eagles, to more contemporary tour-de-forces like Bette Midler as a 70s cross-addicted rock legend in The Rose, and Jennifer Jason Leigh as the falling-apart tatted lead singer Georgia (with a killer rock band fronted by John Doe of X and John C. Reilly on drums).

These are heavyweight actresses, but none quite plumb the depths of Elisabeth Moss, who takes-no-prisoners as this century’s first true 800-pound elephant in the room. Is it possible we didn’t suspect the volcanic potentials of this shrewd actress through seven seasons and 81 episodes of Mad Men, in which she played mousey little Peggy, the secretary who became Don Draper’s lead copywriter and eventually succeeded him at McCann-Erickson as his on-the-rise creative star? Moss has burst into starring roles of staggering breadth and depth both on stage and screen, and she’s built her chops in two other important films with director Perry—Listen Up Phillip and this journal’s previously acclaimed Queen of Earth.

Moss must trust Perry—and vice versa—because actor and director are stretching boundaries galore in what you might describe as an “improvised documentary.” (Actually, that’s how Morgan Neville’s excellent doc, They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead, on the making of Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind, summarizes Welles’ intent in making his long-abandoned final feature. Both are showing in this NYFF, and if you watch Her Smell and Welles’ chaotic mosaic back to back, you may feel you’ve wandered into the same drunken debacle.)

Coherence isn’t what Perry is striving for, through most of the first two hours. He wants you to feel what people who are users and drinkers experience when they’re reeling and wasted, ready to black out in a grungy club with its backstage warren of interconnected drug dens. There’s no attempt to disguise the cameras, sound booms and their operators, who barely get out of the way of the lurching actors. Moss plays Becky Something in an all-girl trio called Something She. Her Smell happens to be the name of the venue that opens the film, and the audience is heavily female. We’re back in the lost 20th century eras of more imaginatively named bands like Catholic Girls, Bikini Kill, and The Slits.

Becky and her bandmates don’t play very inventively, and the head of Paragon Records (a world weary Eric Stoltz) looks exhausted carrying this druggy trio from one bad show to another. Pile in Becky’s estranged husband (Dan Stevens) and their tiny infant daughter, who we immediately start worrying will have her hearing or maybe her head shattered in the din, and you get an idea of the scene. Some viewers may feel it’s a microcosm of Nirvana’s last tour in ‘94 or the collapsing shows of Courtney Love and Hole the same year, when Hole’s bass player Kristen Pfaff died of heroin and Courtney’s drummer Patty Schemel came pretty close to also checking out.

In this drama, hell is also in the recording studio. Here Moss is joined bywhat passes for an opening act, “The Akergirls,” whose names are Cassie, Dotty and Roxie. They’re adoring wannabes until Becky comes steaming out of the control booth heading directly at them, practically spouting steam out of both nostrils. Moss is like the trailers for Broadway’s King Kong with 13 technicians bringing the gigantic animatronic to slow, lumbering life. She seems to be anticipating either a heart attack or an alcoholic seizure, or maybe both, and you can’t take your eyes off her—she’s an original nonstop motormouth, spouting rage and venom at warp speed and sonic stun. When she finally goes down during a performance in a ghastly pool of blood and vomit, you figure she’s a goner.

Only she’s not. Dissolve:

Slowly, Perry brings us out of this nightmare world into a bucolic cabin in the woods. Years have passed. The movie starts behaving like a normal movie. Becky is sober, and her infant daughter has grown into a young girl.

The child is listening to her mom at the piano, singing and playing Bryan Adams’s Heaven. It’s a lovers’ song about finding “someone who’ll turn your world around, bring you up when you’re feeling down.” It’s a bridge-into-sobriety song between mother and daughter, and we’re conscious that Becky has gotten sober faster than any other recovery movie has gotten a drunk mom sober. (The male record for quick recovery is probably a tie between Jeff Bridges’ Oscar-winning performance as a drunk in Crazy Hearts, and Denzel Washington’s cross-addicted airplane pilot sobering up in Flight, an NYFF Closing Night selection in 2012.) There’s none of the hard work that marks, say, Meg Ryan’s journey into recovery and her moving 10-minute qualification before her sponsor and a roomful of recovering alcoholics in When A Man Loves A Woman.

Yet Moss pulls it off. So, does Perry, whose delicate 35mm lensing finally makes Becky’s face, shorn of makeup, look a whole lot older and a whole lot wiser. With her spoken amends to various other characters, she’s ready for—what else but a Paragon Records 20th Anniversary Reunion Concert? It’s not a spoiler but a desperately needed encouragement to tell you that everyone backstage—Becky’s bandmates, her Akergirls opening act, her mom, her label head, her roadies and techies—is sober. There’s a moving clasped-hands circle that precedes the band going on for a joyous rock-out.

Is this real life as musicians—not to mention moviegoers—know it and live it? If you’re in Manhattan in early November, ask anyone standing in line to attend most anything at the Reel Recovery Film Festival. If you miss this year, try 2019—maybe Her Smell will be that fest’s Opening Night. Maybe by then Alex Ross Perry will have gotten the payday he richly deserves.

Her Smell shows Sat. Sept. 29 at 6:00pm and Sun. Sept. 30 at 12:00pm at Alice Tully Hall in Lincoln Center.

Let Us Now Praise Movies; Nicolas Zukerfeld; Argentina, 2017; 15 min.

Jonas Mekas, the beloved head of Manhattan’s Anthology Film Archives, once said there were only two critics who write on Hollywood film “with perception and inspiration: Manny Farber and Andrew Sarris.” Farber, marveled Mekas, “was the first writer, long before Bazin, who brought me to the consciousness of the auteur theory in cinema.”

Nicolas Zukerfeld’s canny, amusing and deeply appreciative short is a tribute to Farber’s search for what he called “Termite Art.” Farber spent his critic’s life in the dark watching for film scenes that “go always forward, eating their own boundaries, leaving nothing in their path other than the signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity.” In Farber’s view, the craftsperson can be “ordinary, wasteful, and stubbornly self-involved, doing go-for-broke art and not caring what comes of it.”

The young craftsman in Zukerfeld’s short is a stationary store clerk (Lucas Granero) who edits and writes for a film magazine on the side and is translating a text from Robert Polito’s compilation of Farber’s film writing. A young woman (Mariana de la Mata) asks him to make a copy of her ID card. Later that night, he plunges into the Polito book and the Farber review. The next day a filmmaker pal comes into the shop—he’s looking for a certain location and thinks Lucas’ parents’ terrace would work perfectly. Lucas takes a coffee break to work on the translation and the ID gal stops by. She speaks and reads English, so he asks her to help translate Farber’s 1943 review of The Ox-Bow Incident. As there are English subtitles, we get to read what Farber has written:

In “The Oxbow Incident,” which is not a horse opera, a dreadful side of human beings is portrayed in a magnificent film. It makes a break in Hollywood’s ugly movie career because the people behind it—William Wellman, Lamar Trotti, Walter Van Tilburg Clark (director, producer and writer) and Henry Fonda, Frank Conroy and Henry Morgan, the players, had their say without losing a scene, a character or a line of dialogue to the Hays Office, the studio or the box office. As the work of unhampered artists, it is for the audience a thrilling experience.

The movie is an examination of an incident—the lynching of three men at The Oxbow, Nevada, in 1885. Aside from its extraordinary indictment of lynching, it shows the failure of liberal men, inspired by justice, when they are opposed by irrational and powerful men of anger. But its soundest, most original declaration is its realistic, pedestrian view of violence, that there is nothing unusual about it in our society, that the men who participated in it did not regard it as violence. The main reason offered by the movie for the success of the lynching is that the majority of the people were either irresponsible, ignorant or moronic…the lynching is a form of self-esteem, and a natural product of such charters as the film had already built.

The introducing to this situation is an example of perfection in movie techniques of camera work and acting. Free for once to play into the character without being pushed around by unlikelihoods, Henry Fonda is magnificent in his projection of an unremarkable, bored, sexually frustrated cowboy, who has been on the range too long, analyzing a nude painting over the saloon mirror. getting drunk fast and beating someone half to death just out of meanness. Alongside, his buddy, Henry Morgan, creates an insensitive, moronic cowboy by a masterpiece of restrained playing. The camera pace is slow, monosyllabic and stolid. It drills persistently into the scene, seeing the event as less important than the behavior of the people making it.

More than anything I would like to emphasize the psychological tension built out of visual movement, which is the movies’ own baby. It is overpowering in such scenes as that of the Negro preacher walking toward the hostile crowd, the pace so felt that the air into which the man walks seems to be pressing him back. I tell you this is a movie. The movie is so fine that its faults are on an astonishingly high level. It chooses to accent the nobility of the victims, in preference to depicting the individual reactions of the murderers.

But the nobility of the lynched men is actually of no consequence so far as the morality of lynching is concerned. The main impact is frittered away in an ending which shouldn’t have happened, since the audience has already felt the guilt of the deed: Everything after the revelation of the men’s innocence is merely slugging away at empty air. The opponent has already gone down.

It is an American legend that Hollywood cannot produce a serious work of art because of censorship, the role of movies as the entertainer of the masses, and the synthetic, mechanical quality of the medium which esthetes say makes it incapable of personal expression.

For the good of everyone, that legend can now be called extinct. “The Oxbow Incident” is a significant moment in our culture. Cheer for it and hope it will not stand alone.—May, 1943

During the latter paragraphs the action has shifted onto Lucas’s parents’ terrace, where a scene is being staged with some minor fireworks that shoot up into the sky. Lucas has promised he’ll clean up any debris left on the terrace.

Zukerfeld’s gem of a short is filled with the “eager, industrious, unkempt activities” that once defined Farber’s Termite Art. The critic’s writing, as you’ve observed, cuts to the quick. There’s not a superfluous observation, not a wasted word.

This short is long on deep knowledge every filmmaker can use.

Let Us Now Praise Movies is part of the International Shorts II program, being shown Wed. Oct. 10 at 6:00pm and Thurs. Oct. 11 at 8:45pm in the Elinor Bunin Munroe theaters.

The Game Changers

The majority of the New York Film Festival’s main slate selections through 56 years have arrived blessed by other major festivals worldwide. That’s one reason this festival doesn’t do “audience awards”; its position is that being chosen for NYFF gives its own global recognition. Meanwhile, NYFF’s downtown counterpart, the Tribeca Film Festival (17 years since its inception in 2002 following 9/11), pioneered separate platforms for documentaries, shorts, revivals and retrospectives, convergence/immersive/games, and, most recently, new television series and pilots. Most of these categories are now integrated within NYFF.

Thus it’s not surprising that the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s curators are pushing their own main slate boundaries into the future with two game changers—two films boasting the kind of bold innovation that cineastes endlessly crave. Consider them together:

La Flor; Mariano Llinas; Argentina, 2018; 807 min.

Long Day’s Journey Into Night; Bi Gan; China/France, 2018; 133 min.

Finding a global audience for Llinas’ nearly 14-hour drama would have been unthinkable before binge viewing, via laptop and smartphone. It’s grown fast and wide. Broadband penetration has changed the way millions of viewers in upscale as well as traditional and transitional cities view movies. If you approach La Flor (The Flower) as a slick, pulpy, made-for-television spy/thriller series with a continuing quartet of vibrant, kick-ass smart women—which for eight or nine hours it seems to be—it’ll probably hook you in to watching something enormously different when its storytelling takes a sudden turn you never see coming.

Director Llinas, who grew up in Buenos Aires, starts his marathon telling us we’re going to watch the same four women play different roles in ten chapters making up six separate stories. We settle in and discover the first three stories have a fanciful familiarity, whipping up their mummies, music biz escapades, sinister spies, exotic South American jungles and creepy centurion spiders secreting a lethal venom that’s been injected into one female’s bloodstream. The production is velvety smooth and pushed along by the director’s urgent, nail-biting voice-over. Every other shot seems to be a gigantic, screen-filling closeup of one or another of the four females, who collectively are known as the acting ensemble Lava Skin.

Take this as a clue Llinas may be anticipating most viewers will be ultimately viewing La Flor via their mobile devices. Also, the pounding, Erich Korngold-styled suspense score has been recorded so loud, you can’t help but believe it’s been dialed up to blast out of a speaker system the size of your fingernail. It’s all lightweight, stylish fun, but the thought may cross your mind that you’ve had these same reactions sitting in the dark of Manhattan’s 25-screen Empire theaters, watching some trashy import that’s bound for the indie graveyard.

It’s at the start of the fourth episode—somewhere in the 6th year of actual production— that everything quite literally falls apart and starts anew. The director, who’s been pushing this easy-going mayhem along, stops filming and steps out to tell his Lava Skin beauties—now costumed as Canadian mounties, cowboys and Native Americans for their next goofy outing—that the episode they’re prepping makes no sense. He’s not quite having a nervous breakdown but he’s experiencing a whopper of a creative block. The actresses don’t disagree, not having a clue what they’re doing.

The director introduces them and us to a new producer who’s come on board; she’s pushy and intimidating and dismissive, and while she doesn’t come to blows with the Lava Skins, it’s a terrible first encounter. As the girls wander off confused and angry, an elderly costume matron who’s been watching their dust up strolls up to the producer from behind, grimly brandishes a gleaming ax, and slaughters her with one powerhouse stroke.

Whoa! Suddenly we’re not watching anything resembling a made-for-television series—the extreme closeups go away, the music score drops down about 30 decibels, and we’re aware Llinas is starting over, leading us this time into a genuine indie art house film, this one involving a considerable variety of stately trees that shelter witches who can actually take flight on broomsticks. —But only for a while.

The fifth and sixth stories are quite special as they appear to retreat into distant and still more distant pasts. One, shot in black-and-white and mostly silent, plays like an ancient Argentinian travelogue involving two picnicking couples who go rowing in a kind of relaxed woodsy milieu, complete with iris-ins and iris-outs. (It’s actually a subtle reworking of Jean Renoir’s A Day In the Country, Renoir’s 41-minute 1936 short.) The quartet does not appear at all.

The final episode finds the four women back, swimming nude in a lake and languishing on rocks, sunbathing. They’re filmed through a thick, gauzy, scrim-like material, though we can see both Corres and Paredes—nine years into the shoot—are now pregnant. A lengthy on-screen text from a 1900 memoir explains a woman’s escape after being captured by a native tribe. It feels like we’re looking at turn-of-century daguerreotypes and that Llinas has turned the clock on Argentinian cinema back to its earliest beginnings in 1901-02.

Can this viewer seriously recommend you invest 14 hours wading through a hybrid that’s hovering somewhere between the multiplex, NYFF’s main slate and its Projections platform (previously known as Views From the Avant Garde)? Just for a day-long immersion in contemporary and historical filmmaking both unexpected and touchingly perplexing?

Absolutely. Without a moment’s hesitation.

The second game changer, Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night, has no relation to Eugene O’Neil’s play. It’s his sophomore feature following Kaili Blues, which won this critic’s lead review from all 27 features viewed in the 2016 New Directors/New Films festival.

That film patiently established a woebegone neighborhood full of souls scraping out livings in ethnographic limbo in Kaili, an unprepossessing city in the hills of southeastern China. It then segued into an unbroken 45-minute tracking shot. following the lead male and female leads in an incredibly choreographed journey through the city’s narrow streets and shops. For a first film, technically, it was unprecedented.

(If Orson Welles had seen it before shooting his then jaw-dropping opening of Touch of Evil in 1958, he might have tried shooting his first 45 minutes without a cut. And even in an era of live 90-minute television dramas shot with bulky multiple cameras, he surely would have failed. He’d have needed steadicams, spy cams, spider cams, assorted drones and perhaps an occasional digital tweak to pull off Bi’s kind of magic. )

Long Day’s Journey Into Night goes Kaili Blues one better. It returns to the same city, with a brooding Huang Jue returning to attend his father’s funeral and discovering an old flame (Tang Wei). Or maybe she wasn’t an old flame and Huang is caught in another of his frequent pipe dreams. The director likes playing with memory, rainy streets and neon signs, unsolved deaths, alienation, jealousy, betrayal. He has a formidable literary source here to draw on—Last Evenings on Earth (1997), the well-regarded ‘failed generation’ short stories of Chilean author Roberto Bolano. At 29 Bi Gan is drunk on filmmaking, and when his hard boiled lead wanders into a local movie theater and dons his 3-D glasses, we put on our 3-D glasses. This is what we’ve come for: a 55-minute long day’s journey into a 3-D night, baby.

There’s great novelty value here. It’s like when you discovered Bwana Devil, the first 3-D movie. (“A lion in your lap, a lover in your arms!”). Then Mitchum, Palance and Linda Darnell in Second Chance (“the first 3-D movie with big stars!”) then The Charge at Feather River (“the first 3-D western!”) then Kiss Me Kate (“the first 3-D musical!”). These were all released in 1953. Long Day’s Journey Into Night is the first 3-D neo-noir with an unbroken 55-minute tracking sequence—by automobile, by cable tramway, by drone! In its way it’s an affecting tip-of-the-hat to Orson Welles, his DP (Russell Metty) and operator (Phil Lathrop) on Touch of Evil. It has a place on the main slate and maybe in a tiny corner of your heart.

La Flor has two viewing options: In three parts (Wed.Oct. 10 at 6:00pm, Thurs.Oct. 11 at 6:00pm, Fri. Oct. 12 at 6:30pm in the Munroe theaters…and in eight parts (Oct.1-4 at 3:00pm and Oct.8-12 at 3:00pm) also in the Munroe theaters.

Long Day’s Journey Into Night shows Tues.Oct.2 at 8:45pm in the Walter Reade Theater and Thurs.Oct. 4 at 8:45pm in the Munroe theaters.

Cold War; Pawel Pawlikowski; Poland, 2018; 90 min.

It’s a brand new drama, but Cold War already looks like it could be a NYFF Revival presentation in this festival, along with wartime chestnuts like Andre de Toth’s None Shall Escape (1944) and Alexei Guerman’s Khrustalyov, My Car! (1998). How many other contemporary directors can transport you to bleakly forlorn corners of post WWII Europe, and then lower a bell jar over your head? You can barely move for an hour and a half, not that you’d want to. There’s not a film on the main slate that remotely resembles Pawlikowski’s latest triumph, though one desperate short—the late Hu Bo’s Man in the Well—bears the unmistakable style of its austere ‘supervisor,’ the Hungarian master Bela Tarr.

Four years ago Pawlikowski’s Oscar winning Ida had an irresistible conflict you could summarize in one sentence: When an orphan in a 60s convent in Poland discovers she’s not Catholic but Jewish, will she take her vows or begin life as a secular Jew? Cold War posits a less daunting dilemma: Can a humorless musician and his domineering, manipulative singer/dancer find happiness together over a decade of touring venues in the throes of rising Communism?

It’s a love story set in the changing tides of history, right up Pawlikowski’s alley. He’s loosely based it on his mother’s life as a touring ballerina through the same 1949-64 era—the beginnings of four decades of tensions between America and the Soviet Union. The director dedicates Cold War to his parents.

His film opens in 1949 Poland, as Wiktor, a composer/pianist (Tomasz Kot) and his producing partner Irena (Agata Kulesza, the ominous aunt in Ida) scout remote rural villages. Outwardly they’re recording villagers singing traditional Polish folk songs. But the company manager, Kaczmerek (Borys Szyc), later changes this focus, searching instead for a “Soviet look” that will be “a living calling card for our Fatherland.”

His meaning is crystal clear when a gargantuan portrait of Russian ruler Joseph Stalin is hoisted behind the singing chorus. The troop is gong to be a traveling caravan for Russian Communism. (Call it a memorable casting choice that Szyc, playing the wily and nationalistic Kaczmerek who shadows this entire movie, vaguely resembles a younger Vladimir Putin. Look at the photo of actors Kot and Szyc standing side by side. This is long before Putin joined the KGB in the 70s, but Szyc’s face and frosty demeanor are eerie.)

The blonde teen Zula (Joanna Kulig) has become the new kid in the ensemble. She’s out of prison on-probation for stabbing an abusive father. Zula has a bell-like vocal register and innocent braids. Costumed like one of the von Trapp sisters in The Sound of Music, she unhesitatingly twirls her way into Wiktor’s bed, though she’s quick to admit she’s “ratting on him” to Kaczmerek, revealing details of the composer’s life and background as the troop makes its way through Germany and France.

Eventually Zula and Wiktor are separated, but reunite in the mid-50s, when American jazz was slowly beginning to transform Paris’ cabaret scene. Zula has married an Italian to escape Poland. Wiktor produces her first solo LP, scores movies and plays piano in intimate clubs. Again they’re drawn to each other, but the film’s most telling scene—Zula cutting loose with a bevy of partners to Bill Haley’s “Rock Around The Clock” and dancing tipsy down the top of a bar—hardly bodes well for a long and happy life together. She says she’s always fully believed in herself but will never believe fully in him.

That’s a universal movie device you’ve watched power everything from A Star is Born in 1937 to La La Land, and Pawlikowski makes it feel fresh here, even shooting in somber black-and-white in the same postage stamp 1.33 to 1 ratio that informed Ida. The concept plays only when the woman is inherently stronger than her partner, which Kulig and Kot maneuver flawlessly. He graciously yields the screen to this tireless schemer, who carries Cold War with complete confidence. With this one Pawlikowski firmly stakes his place in the first tier of world cinema.

Cold War shows Sun.Oct. 7 at 6:00pm and Mon. Oct.8 at 7:45pm at Alice Tully Hall.

Toto; Danny Lee; USA, 2018 ; 17 min.

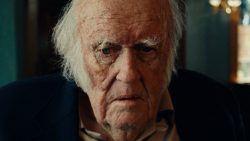

Let us now give 17 minutes of fame to a New York actor who’s worked his heart out on small and big screens for 50 years and counting: M. Emmet Walsh. The quintessential character actor. You’ve seen his big mug playing the coach or the sheriff or the doctor or the judge or the commissioner or the uncle or the dad or the senator or the sanitation man and on and on. He’s gladly died for his art—as the good guy in The Narrow Margin and the bad guy in Blood Simple. The line about him everybody remembers best was penned by Ebert back in the 90s when Roger wrote “no movie with Harry Dean Stanton or M. Emmet Walsh can be all bad.”

Well, here he is in the New York Film Festival, at last in his own starring title role. Walsh plays the retired horror movie star, Toto Z. Arkoff—a sly bow to Samuel Z. Arkoff, who ran the bargain budget AIP studios in the 50s. Toto’s being driven to a horror convention by his manager (an excellent David Jansen, the perfect straight man). He’s scheduled to answer questions on an outdoor stage about how he wants to be remembered, and probably sign glossies for chump change. Huddled in the back of the van, the old guy is pretending to nap while he watches a video of one of his awful movies, The Head.

The van pulls up into a roadside steak house and Toto’s in a foul mood with a headache. The manager orders steak-and-eggs for Toto. The actor spots a row of framed, faded celebrity photos above their booth. He thinks maybe the sullen waitress would like him to sign a picture for the wall. She laughs at the idea and walks away. And Toto throws the hissy fit Walsh has patiently waited for half a century to deliver.

Walsh climbs to his feet and starts yelling like a Lear unleashed that he wants his eggs SUNNY SIDE UP. Then he decides the eggs are just fine and everything’s JUST FINE. Everyone freezes. This goes on, getting louder and louder. Toto lets loose on his poor manager, who’s been enduring this clown for 20 years. Arms akimbo, legs flailing, Toto finally collapses to the floor and we wonder whether he’s going to get up or just die onscreen, this time again, while his steak-and-eggs get cold.

But he makes it to his feet and settles down, and spins a sweet tale of a projectionist’s assistant he once knew who he swore was the oldest man on earth, a big man who complained about “how things had changed ever since the talkies had come in.” And how he’d suddenly died, being run over by a slow-moving bus, wouldn’t you know.

That’s enough plot. You should know writer/director Danny Lee frames Walsh big, lovingly and long in images not unlike that classic limbo shot Richard Avedon once-upon-a-time took of John Ford wearing his eyepatch, looking gnarled and grumpy and at least 400 years old. That’s how Walsh looks. More fabulous than ever.

Keep up the good work, pal.

Toto shows as part of the Genre Stories program Sat. Sept. 29 at 9:00pm and Sun.Sept. 30 at 9:00pm in the Munroe theaters.

My Africa; David Allen; USA/UK, 2018; 10 min.

Virtual reality viewing gives you the advantage of editing your own experience as you watch. Tilt your head up and down, turn your face left and right—new 3-D content reveals itself. Exploring the Namunyak Wildlife Conservancy in northern Kenya is one of this festival’s most rewarding immersive stopovers in their Convergence documentary program.

Your guide is Naitwasha Leripe, an earnest young Samburu woman who tends abandoned and orphaned elephants as well as goats, lambs and giraffes in a well-maintained sanctuary owned and operated by the local community. Narrated in English by Oscar-winning actress Lupita Nyong’o, who was born and raised in Kenya, we follow Ms. Leripe and get a quick but vivid sense of how traditional knowledge works to braid humans and animals in a land threatened by poaching, land degradation and climate change. She believes Africa’s best hope is when villagers agree to protect wild animals.

Director Allen, a four-time Emmy winner, uses Insta360pro at 6K stereo for most scenes. Four-channel and eight-channel Ambiasonic surround sound contribute to the you-are-there sensation. The one scene that reminds us how close both the viewer and animals are to danger follows a herd of wildebeests climbing a dusty hill—crouched at the rim of the hill is a sleek lioness watching for exactly the right dinner she’ll seize with surgical skill. That sequence was shot using SonyA-7 cameras with 180-degree lenses; the rig was encased in bullet-proof glass.

My Africa shows as one of three virtual reality documentary shorts on Fri. Oct.12 at 4:00pm and 6:00pm, and Sat.Oct.13 at 2:30pm and 4:00pm in the Elinor Bunin Munroe Amphitheater.

Roma; Alfonso Cuaron; Mexico, 2018; 135 min.

NYFF’s rich history has included many dramas examining how a society’s wealthy families suffer differently from the rest of us, starting with the festival’s first opening night in 1963, The Exterminating Angel. In that existential portrait by Luis Bunuel, hell was a posh dinner party the guests couldn’t leave. Days passed and upper-class manners began to rot faster than the food. (A ticket in the first four rows of Alice Tully Hall in ’63, and for many NYFFs after that, cost $4.) A more contemporary festival example, Alexander Payne’s The Descendants, observed how land baron George Clooney’s life falls apart amidst Hawaii’s gentle breezes and ocean views.

This festival’s legacy has also been rooted in introducing New Yorkers to unforgettable films defining the suffering of the poor. The Battle of Algiers, Of Gods and Men, Carlos, Black Venus, The Florida Project, Mudbound spring immediately to mind.

Roma, this year’s aptly named Centerpiece, is something else. Named after Colonia Roma, an upscale neighborhood in Mexico City, and set in a turbulent 1970, Cuaron has created a memory film of enduring art that gives separate but equal attention to the well-off and the poor—a monied family and its live-in housekeeper/caregiver—and how everyone encounters suffering and pain in completely different but no less affecting ways.

Roma is already being short-listed for a Best Picture Oscar, (Cuaron’s last picture, Gravity, won him Academy Awards for directing and editing in 2013). The honor it already deserves is instant placement in the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry. Its 65mm wide screen black and white images should ideally be viewed on the largest screen possible—ditto its Dolby Atmos sound design, which should be heard through the most up-to-date theater speaker system. With those caveats, Netflix (Roma’s distributor) can safely bet its investment will be a catalog favorite forever. The film’s Alexa 65 photography is bound to lose some impact in home or mobile viewing, but it will be available in HDR (high dynamic range) picture quality on supported devices.

Cuaron introduces and defines the family we’ll watch with deft strokes: Sofia (Marina de Tavira) is the high-maintenance biologist mom, a micro-managing flurry of nervous energy. Her dutifully helpful mother, Teresa (Veronica Garcia) lives with them. The father, Antonio (Fernando Grediaga) is glimpsed only briefly—he’s a chain-smoking doctor who seems to prefer his books and classical music to Sofia and their four children. Antonio behaves like he’d rather be somewhere else—perhaps curled up on a different sofa with a younger woman.

We intuit almost immediately that the person doing the heavy lifting in corralling, supervising and raising their likable and pleasantly rambunctious youngsters is Cleo, the family’s domestic worker. Warm, polite and quietly affectionate, she’s played by Yalitza Aparacio, a local teacher making her screen debut and speaking in Mixtec. Cleo’s the perfect nanny whether she’s comforting a child or dutifully cleaning dog dirt off the family’s off-street parking space. The household staff also includes a maid, Adela (Nancy Garcia Garcia). All in all, it’s a family with money to burn.

Cuaron, 56, is re-creating much of his own privileged childhood in Mexico City. The furniture we’re looking at came from his original childhood home. The youngest boy is a composite of his boisterous youth. The director is inviting you in long, carefully considered takes to journey back in time with him. He’s operating his own camera and rarely shoots closeups; the rhythms of Roma are invariably developed in slow pans over a wide canvas, which fills with activities that ever-so-gradually capture and win your interest.

A perfect example is the movie theater in which Cleo and her martial-arts lout of a boyfriend, Fermin (Jorge Antonio Guerrero) are sitting in the back row. The view is from behind the two of them, and she’s just whispered to him she thinks he’s made her pregnant, but he’s held more by the movie on the big screen, which we’re half-watching as well. Our attention is divided between Cleo’s look of urgency, Fermin’s stoic gaze, and the action up on the screen. Cuaron is showing us how life works—illusion is often preferable to reality. Sometimes it is reality.

Another scene that splits one’s attention occurs after Sofia and her mom have taken Clio to hospital where she’s been given a first-rate examination by Sofia’s personal physician. Shopping for a crib on the large second floor of a department store, the women’s attention—and ours as well—is slowly drawn to a spectacular street riot. It’s Cuaron’s re-creation of El Halconazo, a terrifying confrontation in 1971 between scores of students and riot police. We watch all this with the women through an upper story window, until they’re briefly confronted by gun-toting students (including Cleo’s lover Fermin) who’ve taken refuge amid the baby furniture. Through it all, no one appears to have forgotten there’s that crib to be selected.

Cuaron takes keen pleasure in creating a mosaic of counterbalancing scenes, contrasting all the lives headed downhill as Cleo’s stomach grows and Sofia’s marriage wilts away. In one brilliantly choreographed scene shot in heavy downtown traffic, Sofia gets her Ford Galaxie squeezed between two massive moving vehicles on either side. Later, in a scene that’s much less amusing (Sofia’s drunk) she slams her sheared Ford off both walls of the family’s home parking space before staggering indoors through the dog poop.

The director also gives us a vacation sequence at a stormy shore buffeted by ominous waves. Two of Sofia’s children wander too deep into the raging surf and it’s Cleo who wades in, desperately trying to find and rescue them. The still shown here only teases what she’ll swim into. Cuaron has created an unparalleled exercise in suspense, an unbroken take that seems to go on forever and looks way past the edge of actor safety.

At NYFF, it’s 56 years since The Exterminating Angel separated the haves from the have-nots, and stripped away their glossy armor. Roma fuses haves and have-nots into a one-of-a-kind study of mutual interdependence that’s a new kind of cinematic adventure. Catch it before it shrinks.

Roma shows Fri.Oct. 5 at 6:00pm and 9:15pm in Alice Tully Hall.

Searching for Ingmar Bergman; Margarethe von Trotta; Germany/France ; 2018; 99 min.

Bergman’s art continues to infuse New York Film Festivals with the mysteries of faith, intimacy and mortality. You could hear a pin drop back in 2005 when Liv Ullman, who starred in ten of his best-known pictures, told a rapt NYFF audience of her frustrations in filming Saraband, the one made-for-television drama Bergman shot in digital. “I always played scenes directly to Ingmar, who crouched right next to Sven Nykvist’s camera lens,” she wistfully recalled. “But with digital, Ingmar had to be across the room, watching a little monitor. I had several different cameramen filming me, and no Ingmar. I was lost.”

In Liv and Ingmar, the feature documentary by Dheeraj Akolkar shown at the 2012 NYFF festival and a critic’s choice, Ullman is the sole narrator and on-camera presenter, describing not just her movies with Bergman starting in 1966 with Persona, but the five years in which she and Bergman lived together and had a daughter, Linn. (He fathered eight other children with seven wives.) Ullman concluded with the last day of his life in 2007 at his remote home on Faro Island in Sweden, when she visited him and he gave her a final note, tucked into a child’s teddy bear.

Searching For Ingmar Bergman by Margarethe Von Trotta is a vital part of this festival’s Retrospective section. It’s the U.S. premiere of what surely will stand as the defining Bergman portrait—at least in film—by the acclaimed German director, whose Hannah Arendt, Rosa Luxemburg and The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum are probably most familiar to American audiences.

Von Trotta, now 76, was in part drawn to Bergman because he’d called her Marianne and Julianne (1961, known today as The German Sisters) one of his personal favorites. She’d also been transformed seeing Persona—every filmmaker alive who watches Ullman (playing a nurse) and her mute patient (Bibi Andersson) gradually change personalities until they literally merge as one, has to rethink their concept of women in film. Von Trotta may have been frustrated at how little footage exists of Bergman talking about his writing and directing, and even fewer clips of him directing on film or stage sets.

Bergman spoke at length in print—Conversations with Bergman (Olivier Assayas and Stig Bjorkman, Cahiers du Cinema, 2006); Ingmar Bergman: Conversations (Raphael Shargel, University Press of Mississippi, 2007); and Bergman on Bergman (Simon and Schuster, 1974) ) are among the most comprehensive books of interviews on his art and craft. But Von Trotta’s search would have to be through her own eyes and the sensibilities of others.

And so she shoulders the task of personally deconstructing the timeless classics like The Seventh Seal, Through A Glass Darkly and Hour of the Wolf, intertwining her own fluid observations with the memories of relatives, writers, actors (including Ullman), his longtime producer Katinka Farago and other artisans who worked with Bergman, and mixing in a soupçon of delicious conversations with film directors including Assayas, Bjorkman, Carlos Saura, Mia Hansen-Love and Ruben Ostlund.

The result is a master class on not just how Bergman built movies around eternal values and the human condition—the subjects that surface first in Bergman discussions, usually in the context of religious experience or death— but how he wrote about women and particularly the many women he loved and married. Working with her co-directors Bettina Bohler and Felix Moeller, Von Trotta assembles a string of remarkable insights into the Swedish master:

As Bergman’s religious guilt fell away, he was able to focus purely on humanity, gradually losing God from his writing focus. (Jean-Claude Carriere, writer).

By exploring magical and supernatural films that centered around his female characters, he could freely expand the concept of the liberated woman—acted by Ullman, Bibi Andersson, Harriet Andersson, Ingrid Thulin, Gunnel Lindblum, Rita Russek. (Assayas)

In both his writing and his direction, Bergman was reinventing and reliving his own childhood, not the world of any of his own children. He films youngsters as though they’re him. (Von Trotta)

“He’d say to his ladies, when you’re pregnant, then I know you love me…And then he’d leave them.” (Daniel Bergman, son and director)

Though he spoke of always supporting and nurturing his casts, Bergman darkened and chilled rehearsal rooms, occasionally down to 12 degrees. Ullman has spoken of hours spent freezing in a boat shooting The Passion of Anna. Bergman was a director of dreamers and of dreams, and the film he ran more often than any other in his own viewing room was The Phantom Carriage, a 1921 tale of a broken man seeking forgiveness from his family. It was directed by Victor Sjostrom (who Bergman cast as his old man in Wild Strawberries), using double exposures and semi-transparent imagery.

Bergman kept strict visiting hours at his solitary home on the island of Faro, where he pre-planned his own funeral and burial with highly detailed instructions. Mia Hansen-Love slept nights on Faro in the process of shooting a recent movie, and reports she felt a cold, ghostly presence that was frightening. Von Trotta seems to echo that unease. The last shot in her search frames her standing beside a huge black rock on the desolate beach, exactly where the figure of Death hovered in The Seventh Seal.

Searching for Ingmar Bergman had its American premiere October 8 in the Elinor Bunin Monroe theaters.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s reviews of DOC NYC, America’s largest documentary festival, coming November 8-15.

Regions: New York City