“There Were No Laws Against It Then”

Abuse, Stardom, and the False Promise of Sexual Revolution in 1960s Hollywood

Kerry McElroy writes about Elizabeth Taylor, Hugh Hefner, and other icons of mid-century culture for this sixth series installment of Bette, Marilyn, and #MeToo: What Studio-Era Actresses Can Teach Us About Economics and Rebellion, Post-Weinstein.

The 1950s was the era of the frustrated housewife and The Feminine Mystique in American life. By the early 1960s, the social tumult that had been simmering below the surface finally began to boil over for women, minorities, and in anti-Vietnam protest. But with so much change in the air, how did American corporate male interests respond? Further, in an era when women were beginning to throw out their girdles, read feminist theory, and join consciousness-raising movements, what became of the most objectifying business of all—Hollywood? As has happened over and over again in Hollywood history, things didn’t go as we might expect. The 1960s represents, like previous decades, a lost opportunity for women as regards equality in the film industry.

One particularly apt late studio-era Hollywood dynamic that demonstrated mistreatment as still the norm was the relationship between director and actress. The quintessential 1960s director, Alfred Hitchcock, had a typical albeit extreme version of the attitude that actors were annoyances—bodies to stage, voices to recite lines—who got in the way of a director’s vision and genius. When it came to gender, he once said, “‘I always believed in following the advice…‘Torture the women!’” (Spoto xix). Tippi Hedren, his most famous leading lady, felt the brunt of his misconduct.

Hitchcock’s 1960s behavior—a blending of tyrannical work practices of jealousy and stalking—was not novel in Hollywood. His treatment of Hedren stands, however, as an acute example of the era’s director-actress horror story. He bullied her relentlessly on the set of The Birds, including a “two-minute assault scene [that] required a full week of eight hour days of shooting, days that left Tippi Hedren on the brink of emotional and physical collapse” (Tatar 38). In the ultimate irony, animal welfare specialists turned up to monitor the treatment of the birds, but no one did the same for Hedren (Ibid.).

Hedren rejected Hitchcock’s casting couch come-ons. As she said in an interview, “He made it very clear what was expected of me, but I was equally clear that I wasn’t interested” (Hedren qtd. In Oglethorpe). When she spurned his advances, the director’s passion soon turned to spite. Hitchcock became the worst type of stalker-boss, jealously monitoring anyone with whom Hedren had social relationships. In the face of Hedren’s steadfast efforts to maintain her dignity, Hitchcock resolved to destroy her career. Hitchcock refused to release Hedren from her contract to work with any other directors. She said candidly:

“He trapped me and ruined my career. Producers would ring up…offering me parts and Hitchcock would simply tell them that I wasn’t available….For two more years, he kept me under contract, paying me $600 a week….There was talk of me receiving an Academy Award nomination but he stopped that before it even got started” (Ibid.).

Hedren’s candid reflections are useful in this #MeToo movement, especially in light of the reckoning that has followed the Weinstein scandal. She is frank in describing a culture of enabling assistants and wives, individuals who knew that the abuse was going on but were afraid or unwilling to intervene. Hedren once recalled a disturbing interaction with the director’s wife: “She knew full well what was going on. I said: ‘It would just take one word from you to stop this’, and she just walked away, with a glazed look in her eyes” (Ibid.).

In her older age and recent interviews, Hedren has demonstrated a sophisticated connection between her own treatment in pre-feminist Hollywood and today’s #MeToo moment. Hedren’s adoption of a modern feminist lexicon for what she endured in the 1950s and ‘60s is revelatory. In a recent interview, Hedren described the abuse she endured, including the mental, sexual, and financial, saying “it was nothing new in Hollywood in those days.” She added, “You have to remember that this was a very different time from now and Hollywood was a very different place….Of course, sexual harassment still occurs, but there are far more safeguards in place to prevent it, far more awareness and knowledge of the dangers….There were no laws against it then,’” (Hedren qtd in Hiscock). Since 2017, Hedren has given interviews arguing how difficult it was for women to speak about stalking, harassment, and sexual assault in those terms during her working years. It was only in later life that she recognized that what had been “normal” treatment in the Hollywood of her youth was actually verifiable abuse and assault. After the Weinstein scandal broke, Hedren went on record saying that his abuse reminded her of Hitchcock’s (Teeman).

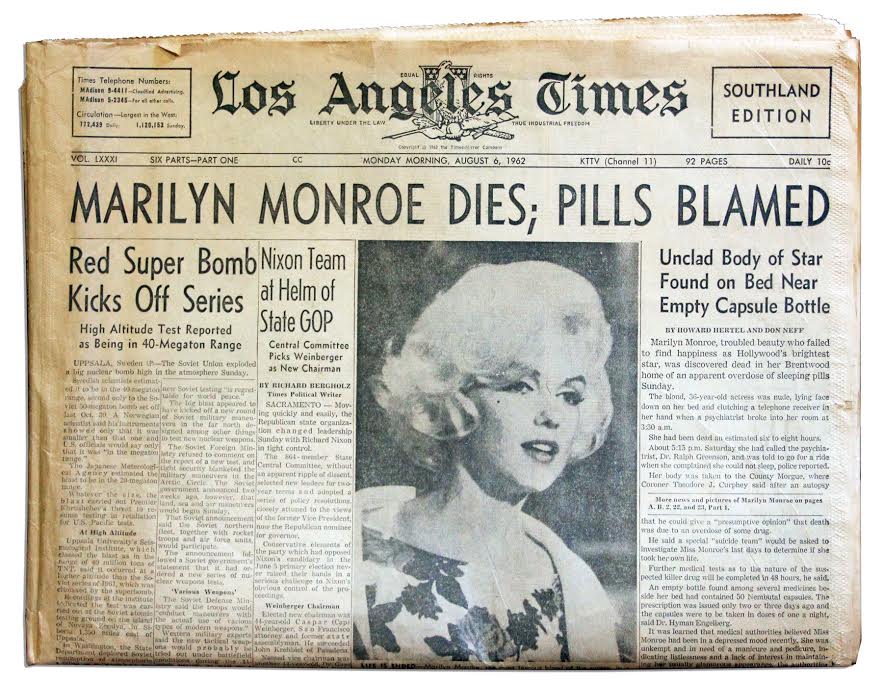

For an example of a woman of the 1960s generation who never got her #MeToo moment, we can again turn to the biggest global star of the mid-twentieth century. In the last article, we looked at Marilyn Monroe as something of an economic sociologist of Hollywood. By the 1960s, however, her long career in Hollywood had taken its toll. As has been well-documented, the final years of her life were marked by mental illness and abuse. Living for years under toxic working conditions, which included addiction brought upon by studio-prescribed drug cocktails, had had a deteriorating and dangerous effect on Monroe’s stability. The nexus of trauma and mental illness that affected so many star-actresses of her era reached a kind of apotheosis in the cultural figure and real life biography of Monroe. As such, she became a subject of inquiry for many important feminists of the Second Wave era.

Andrea Dworkin, the anti-heterosexual, anti-porn activist, may seem like an unlikely person to write about Monroe. But in fact, Dworkin makes an extremely astute point about Monroe’s psyche and what the industry’s conditions had done to women like her. Whether or not Monroe committed suicide or died of accidental overdose, society must confront that she “hadn’t liked It all along—It—the It they had been doing to her, how many millions of times?….Her apparent suicide stood at once as accusation and answer: No, Marilyn Monroe, the ideal sexual female, had not liked it,” (Dworkin qtd in Steinem 179). One need only look at stills of the nighttime shooting of the famous subway grate scene in The Seven Year Itch, where hundreds of male passersby who had formed a mob ogled Monroe in her underwear, to see the violence (and violation) underlying her ostensibly glamorous life.

As the country was “awakening” through political protest and the sexual revolution, things were, counter-intuitively, often getting worse for women in Hollywood. Where might we look, then, for optimism in this decade? As the studio system fell apart, one megastar, Elizabeth Taylor, was able to use its weaknesses to her advantage and become a power player in her own right. She is intriguing as an economic actor of the late studio system.

Elizabeth Taylor was born in 1932, part of the last generation tied to the old-style indentured servitude of the studio system. Taylor had gone from an MGM child star of the 1940s to the most marketable sex symbol in the world. And yet, Taylor’s inexperience with structural abuses such as the “casting couch” demonstrates how certain women (particularly valuable young stars) were shielded from the grim realities facing most working actresses. Taylor wrote in her 1964 memoir, “I was too young to know why all of a sudden a young woman would be blackballed and never heard of again. Evidently, that casting couch bit did happen. Of course, I never even heard about it until years later,” (Taylor 12).

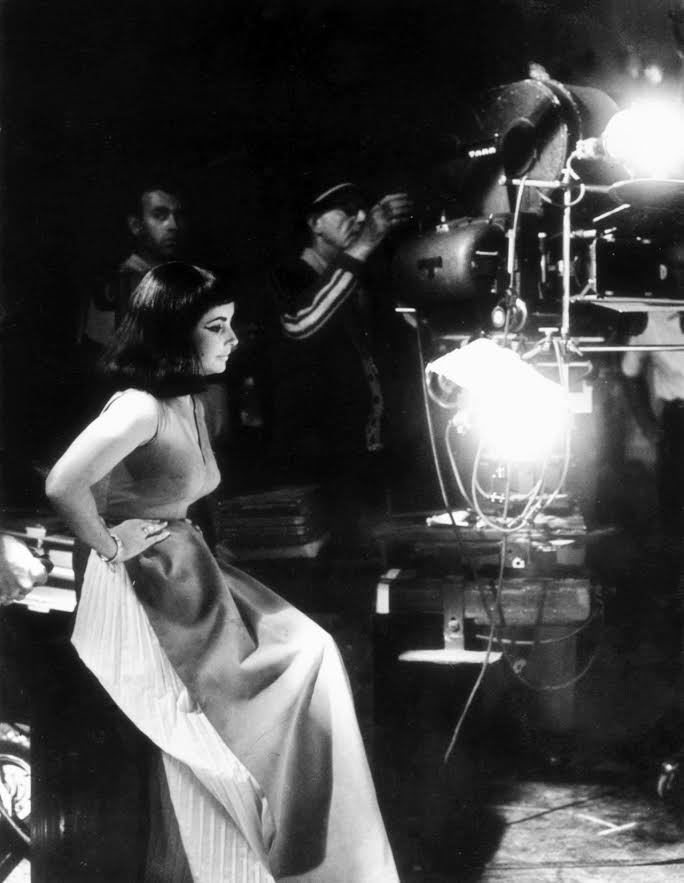

Taylor’s long history with the system and personal wit make her a particularly interesting actress/truth-teller. Of her career trajectory, she once said: “To do National Velvet I signed a contract with MGM—and became their chattel until I did Cleopatra” (Ibid.). Taylor was irreverent about the upbringing she received at MGM, noting how people called MGM’s main management building “The Iron Lung”: “You know, the executives tell you just how to breathe,” (Taylor 14). She was equally scathing about the lack of bodily autonomy and the policy of suspensions if a woman chose to have a child, noting wryly that “every time I got pregnant, kind-hearted old MGM would put me on suspension,” (Taylor 45). Taylor scornfully called MGM head Louis B. Mayer “Big Daddy,” mocking a man who told all his employees they were his children and forced them to celebrate his birthday (Taylor 15). As the studios disintegrated, Taylor became an increasingly savvy negotiator. In one dispute, she yelled at Mayer and told him to go to hell. She never went back to his office. This pattern of rebellious independence culminated in her finally becoming the first woman to earn a million-dollar salary (Taylor).

Taylor’s personal life scandals of divorces, affairs, and “husband-stealing” (which began in the later years of the 1950s) had made her infamous by the 1960s—yet more popular than ever. The studios understood that as long as Taylor played sexy and sinister opposite an innocent blonde girl-next-door, she was worth millions. Taylor’s villainous image actually helped her to become a very wealthy woman. As it turned out, everyone wanted to cash in on the notoriety of Taylor and her affairs. Just as the sexy man-stealing vixen narrative reinforces patriarchal politics, it also reinforces misogynistic capitalism too. Lawrence Harvey, Taylor’s co-star in Butterfield 8, put it bluntly: “The bitch is where the money is,” (Harvey qtd in Walker). In the tabloid press, Taylor became “the black widow” and “the woman you love to hate” (Photoplay 1960).

Taylor’s most massive infidelity scandal, her affair with Richard Burton on the set of Cleopatra in 1962, was connected, in the minds of worried male executives, to the failing studio system itself. In a grave New York Times article about the future of the film business, Taylor and her behavior were specifically decried as a factor in what looked like industry catastrophe: “The current temperamental shenanigans of Elizabeth Taylor during the shooting of Cleopatra in Rome are also regarded with resentment and grave distraction by certain closely involved parties in this town. Little humor is had hereabout from the gag, ‘Liz fiddles while Hollywood burns,’” (New York Times May 6, 1962). The following month, insiders anxiously awaited a response to the gargantuan and troubled Cleopatra (New York Times June 1 1962). With hundreds of millions of dollars on the line, their anxiety demonstrates just how much power Taylor held in late-studio Hollywood. Her position was unlike any actress before.

Having said this, Taylor’s success stands, in many ways, alone. Much of what we’ve learned from actresses of this era, especially those who’ve added their voices to the #MeToo conversation, confirms that the 1960s was not a liberating era for women in Hollywood. Sexual exploitation, if somewhat repackaged, remained rampant.

Even as the studios collapsed, billions were made on the sexualizing of the industry and its actresses. Once again, it was men making money off of women’s bodies—just new men, pushing new, looser, sexual mores. Now, if an actress didn’t want to go along with a casting couch quid pro quo, she would be deemed “square” or “conservative.” Clothes grew skimpier, roles demanded more sex and nudity, and misogynistic advertising and pornography crept into the public space. All of this was part of very deliberate efforts by men to monetize the idea that ever more present sex was “modern” and “liberating.”

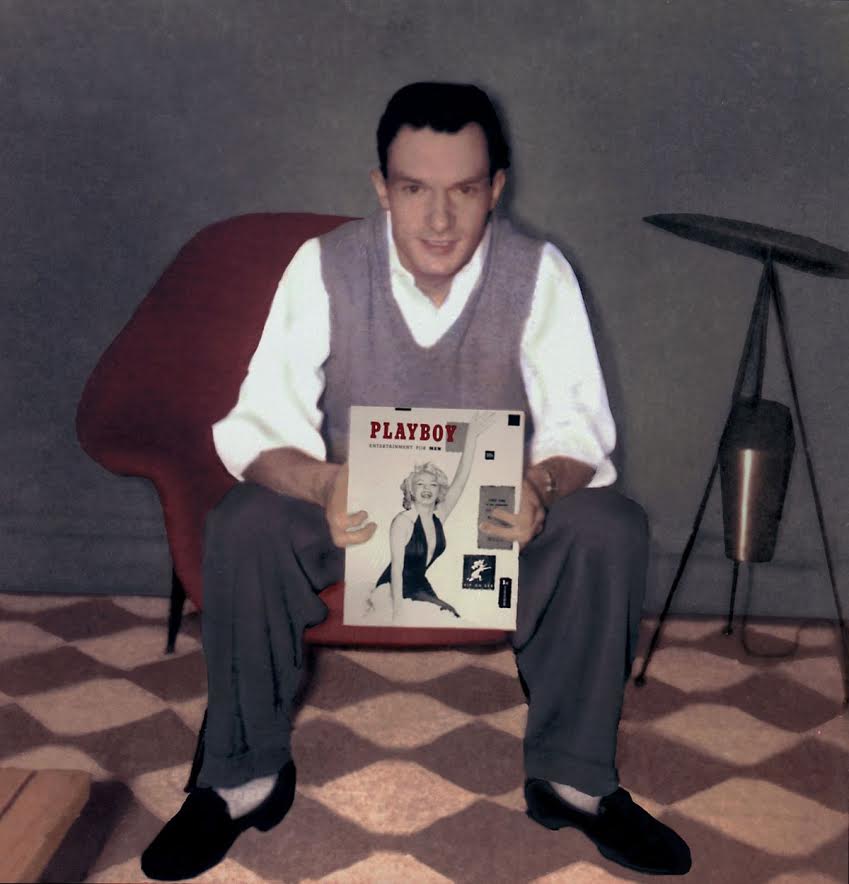

No one is more tied to the phony, exploitative, misogynist, capitalist side of the 1960s “sexual revolution” than Hugh Hefner and the rise of his Playboy empire (Valenti). It is not coincidental that the ideal woman became a “sex kitten,” or that a pornographer like Hefner could rise to the height of glamorous sophistication with an empire built on the dehumanization and exploitation of women. It would be remiss not to connect Hefner, his practices and legacy, with the earlier discussion of Marilyn Monroe and the abuses that brought about her untimely death. It is ultimately fitting, in ways this series has pointed out, that the young, no-name Hefner put his name on the map by selling nude photos of Monroe (a star he did not know) against her will (Kane). In keeping with the sociopathic male capitalist culture that lauded Hefner and his “business empire” until his death in 2017, Hefner gained initial attention through cruel exploitation. Even more fitting, and perfectly emblematic of pathological Hollywood power relations and treatment of women, is how Hefner stalked Monroe even in death by buying a plot so he would be buried next to her (Kang). The fact that Monroe’s final resting place is next to a stranger who pimped her out for his profit is sickening.

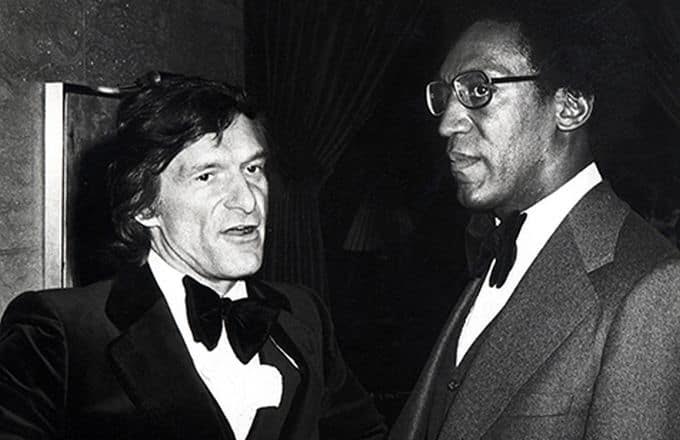

While women around the world were rising up for worker and spousal rights, the cultural imagery of 1960s Los Angeles was the Playboy Mansion and The Valley of the Dolls. Serial rapist Bill Cosby, Hefner’s closest friend, operated with impunity in Hefner’s clubs. As one of the Cosby survivors, PJ Masten, explained in the now-iconic 2015 survivors’ expose in New York magazine, “I told my supervisor at the Playboy Club what [Cosby] did to me, and you know what she said to me? She said: ‘You do know that that’s Hefner’s best friend, right?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ She says to me: ‘Nobody’s going to believe you. I suggest you shut your mouth,’” (Masten qtd. In Malone).

The 1960s “Bunny,” “Playmate,” and starlet culture depended upon women arriving in Hollywood in droves, willing to be objectified. Not since the 1920s was sexual exploitation so par for the course. The axiom that “if you won’t do it, there are a hundred girls waiting behind you who will” accelerated to extremes in the 1960s. As Danae Clark has written of actresses and particularly applicable to this era, “They must be induced to ‘live’ their exploitation and oppression in such a way that they do not experience or represent to themselves their position as one in which they are exploited” (Clark 21).

While women in other parts of the country made intellectually-driven gains in feminism, creating effective campaigns for changes in employment practices and developing the first domestic violence shelters and rape crisis centers, Los Angeles remained dominated by Hollywood and its calcified, dangerous views of women as sexualized bodies and commodities. As a result, a feminist awakening simply did not happen in Hollywood for decades. One of the reasons the #MeToo moment of 2017 was so earth-shattering and monumental was because it was finally Hollywood’s feminist moment, fifty years overdue.

But even in the country’s most masculinist-objectifying industry, which depended upon women’s continued acquiescence for its perpetuation, there were tiny acts of rebellion and strategy that predated #MeToo and Time’s Up. Studying the current 2016 groundswell of truth-telling by older women around their victimization by Cosby from the 1960s to the 1990s, for example, is an excellent case in point. What are now called “whisper networks” on social media, in which women warn women about predatory men, preceded the digital era. In the 1960s, the women who worked in the nightclubs and Playboy Clubs would warn one another to watch out for certain men, as women have been doing for centuries. It is all the more fitting, then, that in the digital age, these women are able to form a community across race and geography to help and warn one another again—and to finally have their #MeToo moment after three, four, or five decades. As Masten says, “I started getting private messages on Facebook from other former Bunnies: ‘He did me too, PJ. He got me too.’ There’s a couple of websites, ‘We believe the women,’ and Cosby sites too that we all created. And we talk, all the survivors,” (Masten qtd in Malone).

To conclude, the 1960s is a particularly sad decade for the history of women in Hollywood. While the rest of the world was opening up to women’s liberation, feminism failed to remake Hollywood. In fact, as women were reaching equality on economic and political fronts in other areas, American film even instead saw new heights of violent and pornographic misogyny. The decade saw a new, young generation of independent male filmmakers who mainstreamed rape and murder scenes and porn aesthetics under the guise of youth rebellion. As Brian De Palma remarked cheerfully on the makeup of the slasher film as mere genre convention, “I don’t particularly want to chop up women, but it seems to work,” (Knapp qtd De Palma ix). The rise of woman-mutilating and killing in film at the same moment of ascendant women’s liberation in society is something that theorists of feminist gains and backlash like Naomi Wolf or Susan Faludi would consider no coincidence.

Further, the 1960s represent a separate failure, a missed opportunity on the economic front. The crumbling of the old, all-powerful studio system should have opened a door for women to finally take on more professional power and voice in the system. Instead, new models—the rise of Hefner’s empire and the explosion of the porn industry, to name a few—merely reproduced white, misogynistic hegemony.

In the next article, the series conclusion, we will end with a note of hope as to how the injustices that accelerated from the 1960s onward were, in some ways, finally brought to a rather abrupt halt in 2017. We will look to manifestos and marches but also to new understandings of history, economics, and institutions that may finally bring about permanent change in Hollywood.

References

Clark, Danae. Negotiating Hollywood: The Cultural Politics of Actors’ Labor. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota, 1995.

De Palma, Brian and Lawrence Knapp. Brian De Palma: Interviews. Oxford: Mississippi, 2003.

Dyer, Richard. “First a Star: Elizabeth Taylor.” Only Entertainment. Ed. Richard Dyer. Routledge: London, 1992.

“Eddie: ‘I’ll take Liz back!”. Photoplay, 1964: n. pag.

“Eddie sues for Liz’ child because ‘Liz lives in sin’!” Photoplay, June 1965: n. pag.

“Elizabeth Taylor’s public image is subject of filmmakers’ study.” New York Times 1 June 1962: n. pag.

Faludi, Susan. Backlash: The Undeclared War against American Women. New York: Crown, 1991.

“Fox says Taylor reissues are not a popularity test.” New York Times, June 2, 1962.

“How much more can Liz take?” Photoplay, 1960. n. Pag.

“Jacqueline Kennedy vs. Elizabeth Taylor – America’s two queens! A comparison of their day and nights! How they raise their children! How they treat their men!” Photoplay. June 1962: n. pag.

Kane, Vivian. “Hugh Hefner Is Still Exploiting Marilyn Monroe, Even In Death.” The Mary Sue. September 28, 2017.

Kang, Biba. “Hugh Hefner Has Immortalized Himself As A Disgusting Creep By Getting Buried Next To Marilyn Monroe.” The Independent. September 29, 2017.

Kelley, Kitty. Elizabeth Taylor, the Last Star. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981.

“Liz’ butler tells everything he saw.” Photoplay, July 1962.

“Liz screams! Mob beats up Burton!” Photoplay, April 1963.

“Liz Taylor: does God always punish?” Photoplay, April 1960.

Malone, Noreen. “I’m No Longer Afraid’: 35 Women Tell Their Stories About Being Assaulted by Bill Cosby, and the Culture That Wouldn’t Listen.” New York, July 26, 2015.

“Miss Taylor Is Chided: Vatican Weekly Questions Her Right to Adopted Girl.” New York Times, April 13, 1962.

Oglethorpe, Tim. “Hitchcock? He was a psycho: As a TV drama reveals his sadistic abuse, Birds star Tippi Hedren tells how the director turned into a sexual predator who tried to destroy her.” Daily Mail Online. December 21st, 2012.

“Out of the past, into the future with Miss Taylor.” New York Times, April 12, 1964.

Paglia, Camille. “Elizabeth Taylor: Hollywood’s Pagan Queen.” In Sex, Art, and American Culture. New York City: Vintage, 1992. Paglia, Camille. 1992.

“Period of Change: Imminent Change Has Hollywood Film Colony on Edge.” New York Times. May 6, 1962.

Sheppard, Dick. Elizabeth: The Life and Career of Elizabeth Taylor. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. 1974.

Spoto, Donald. Spellbound by Beauty: Alfred Hitchcock and His Leading Ladies. Three Rivers Press (CA), 2009.

Steinem, Gloria, and George Barris. Marilyn: Norma Jeane. New York, NY: New American Library, 1988.

Tatar, Maria. Lustmord: Sexual Murder in Weimar Germany. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Taylor, Elizabeth. Elizabeth Taylor; an Informal Memoir. New York: Harper & Row, 1965.

Valenti, Jessica. “Hugh Hefner Didn’t Start The Sexual Revolution- He Profited From It.” Marie Claire. September 28, 2017.

“Vote today: can you forgive Liz Taylor?” Photoplay, July 1962.

Walker, Alexander. Elizabeth: The Life of Elizabeth Taylor. New York: G. Weidenfeld, 1991.

“Was her son told Liz is leaving Eddie?” Photoplay, October 1960.

“What Burton does to Liz that no man ever dared! 7 pages of love photos.” Photoplay, September 1, 1963.

“What Liz is doing to keep Burton! The photos they never knew were being taken.” Photoplay, September 1962.

“What Liz knows about love – that other women don’t.” Photoplay, September 1961.

Wolf, Naomi. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used against Women. New York: W. Morrow, 1991.

Regions: Los Angeles