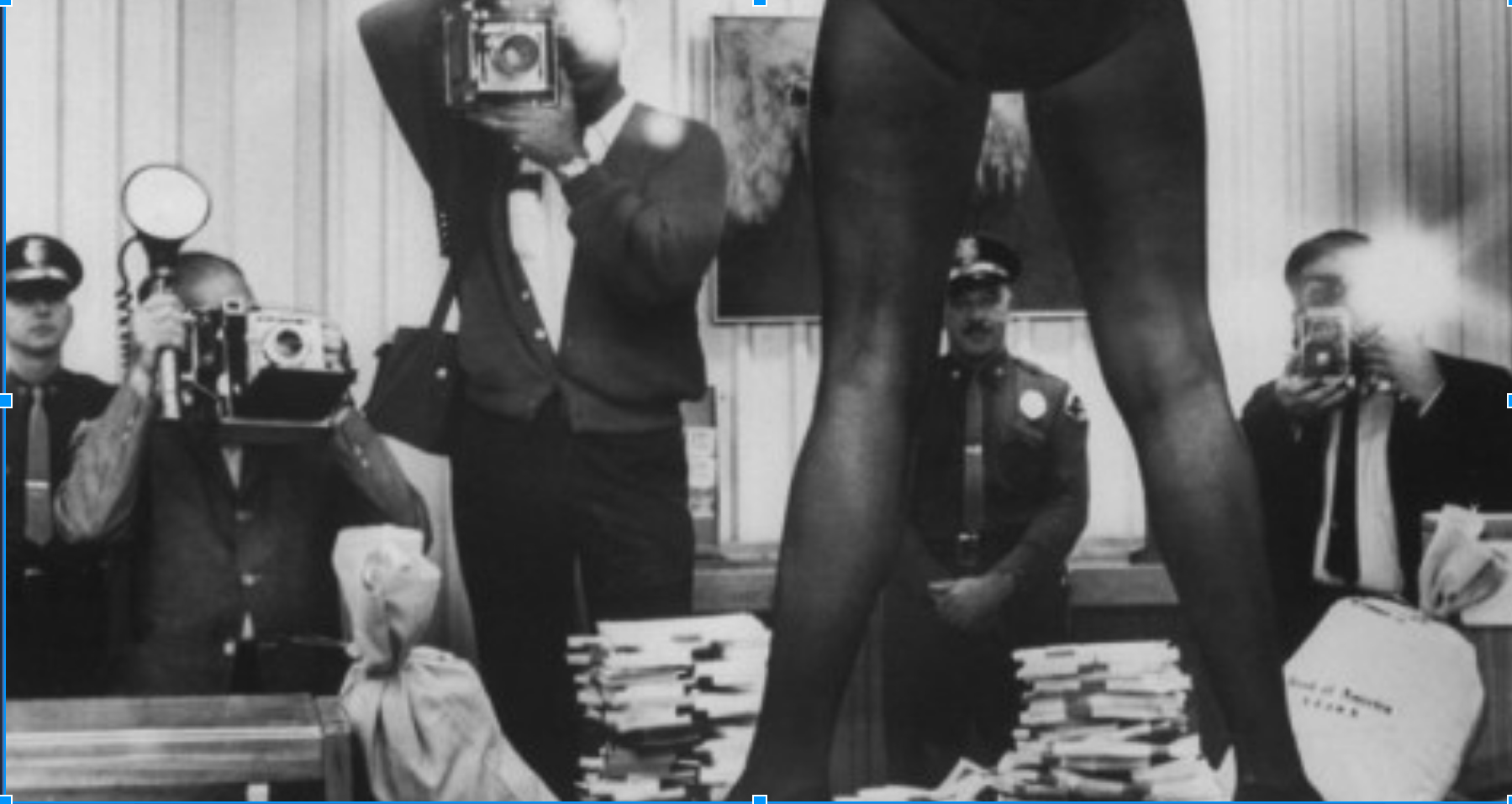

New Series: Bette, Marilyn, and #MeToo

What Studio-Era Actresses Can Teach Us about Economics and Resistance Post-Weinstein

It’s the summer of 2018, and the initial Weinstein scandal has evolved from shock and rage to a moment of true possibility for lasting change. “Time’s Up” and other women-driven initiatives appear promising and liberating. Yet underlying the reality of entrenched sexual assault and harassment (the focus of much current public scrutiny) is a question of economics: who controls the money?

The truth is that the crimes of Weinstein and his ilk are first and foremost a systemic capitalist problem, in a hyper-capitalist industry. Despite many political and economic gains, hard won by feminists over the course of the twentieth century, male capitalists have remained firmly in control of every aspect of the film business, and this dominance has been largely unchallenged. The rise of independent film and the passing of the studio system have done little to alter this reality.

This moment—when women are combining their voices to demand justice and achieve self-determination— is also a perfect time, perhaps counter intuitively, to look back. “Golden Age” studio-era women worked under the double grip of a Fordist industrial system and a heavily patriarchal, misogynist one. Still, they sometimes managed to outsmart, succeed, and thrive. If we could bring a Mary Pickford, Bette Davis, or Hattie McDaniel into a #MeToo listening session, what wisdom might they offer—not just about the traumas of harassment or assault, but about how to stand up for oneself economically in a rigged system?

This bi-monthly series will chronicle studio-era women, including Louise Brooks, Olivia De Havilland, and Elizabeth Taylor, who carved out spaces of autonomy in a decidedly male-controlled film industry at the height of its exploitative powers. Spanning the 1910s-70s, each article will profile a single actor (all women who struggled for financial independence and career control). At the same time, the articles will illustrate the strategies of resistance, unique to each decade, by highlighting disputes over suspension, savvy contract negotiations, court cases, and whistle-blowing. As filmmakers of all genders attempt to reckon with the newly shifting terrain of 2018, it’s a perfect time to look to history and follow the money.

Essays appearing in this series:

“Hollywood Was a Matriarchy”: The Forgotten Decade of Women’s Power and Independence in Film

Regions: Los Angeles