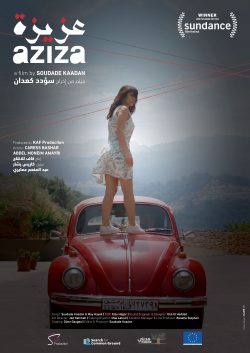

Sundance 2019: Writer/Director Soudade Kaadan

Neil Kendricks Interviews Aziza’s Filmmaker on Transforming her Experiences as a Syrian Exile into an Award-winning Short

PARK CITY, Utah — It is an almost impossible task to wrap one’s head around the shifting complexities of the Syrian refugee crisis. For Syrian Writer/Director Soudade Kaadan, however, the global dilemma is grounded on her home turf and her best strategy to set the record straight is by zeroing in on a married couple’s everyday plight, which she does through the darkly comedic lens of Aziza, winner of the Short Film Grand Jury Prize at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival.

Throughout the 13-minute dark comedy, Kaadan and her co-writer May Hayek invite viewers to hunker down and ease-drop on a rocky patch in the couple’s relationship as the husband teaches his young bride how to drive his beloved Volkswagen beetle named Aziza. As one of the most original short films featured at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival, this unconventional love triangle between a husband, his wife and -wait for it – the family car plays out with the jolting humor of an absurdist comedy that would have made avant-garde playwrights Eugene Ionesco and Samuel Beckett smile. Funny, caustic and, ultimately, moving, Kaadan’s unorthodox, cinematic portrait of domestic life among Syrian refugees wins viewers over by putting us in the car’s claustrophobic confines as the bickering couple struggle to salvage and heal their wounded love.

Born in France, Kaadan studied theater criticism at Syria’s Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts and filmmaking at Saint Joseph University Institut des Etudes Scénique, Audiovisuelles et cinématographiques (IESAV) Lebanon. Kaadan understands that the most direct route to making her story universal is to render the small nuances of her fictional characters in exile ring true. As a class standout among the 73 short films showcased at this year’s Sundance, the filmmaker puts an all-too-human face on a crisis that feels distant and unapproachable to Western audiences. Through its experiments in subjectivity laced with Kaadan’s biting humor, Aziza makes us feel the psychological toll on individual lives that are too often obscured and lost behind the glaring headlines of conflict in the Middle East.

In this Q&A interview with Kaadan, the writer-director of the award-winning feature-length film The Day I Lost My Shadow, which won the 2018 Venice Film Festival’s Lion of the Future award, opens a window into the creative process behind Aziza and the process of crafting the most unusual driving lesson as a tour across the battered landscape of our shared humanity under duress.

NK: Comedy has the ability to cut through our defenses enabling us to see life through the eyes of another individual’s perspective or even another culture’s point of view with more clarity and empathy. What was the catalyst that triggered the darkly comedic story for your film Aziza? Are the story and its conflicted characters based on personal observations in your own life?

SK: The catalyst element was time. You only need a little bit of time to be able to tell your story with humor, as comedy is tragedy plus time. I put all my sorrow, shock, and pain in my feature film The Day I Lost My Shadow, which was liberating for me, so I could tell my story as Syrians in exile, the diaspora and refugee states with humor in my next films.

All my films are based some how on my personal experiences since I was the writer and director of all my films. The story of Aziza is also based on my own experience as a Syrian living in Lebanon in exile state. I also tried to learn driving despite the horrible, chaotic traffic of Lebanon and couldn’t make it. The main character in the film could only drive in her Syrian car with all the racism surrounding a Syrian car in Lebanon—once she imagined a parallel universe, a Damascus that doesn’t exist now.

NK: How did you develop your specific approach to mise-en-scene with the limited locations to keep the narrative focused on the couple?

SK: My main concern in the film as director is how to make the car looks like its driving in the streets while it is not moving it at all. How in decoupage, effects and actors, and mise en scene, we can convince and play with the audience with this idea: The car is moving only in the head of the Syrian characters while it is standing still in the darkness of a parking lot in exile. It represents the fear to go out; the fear many Syrians find themselves trapped in once they are in a new forced country that they couldn’t choose and facing racism around them. It was also a low-budget movie. From the beginning, I was thinking to make a movie in three locations with two great actors. I wanted to explore with them how we can explore a simple story of driving in exile into madness without driving the car. I felt it would be a beautiful challenge, so I chose only three locations for the film and three actors: the two main leading actors and the car Aziza.

NK: As a fellow filmmaker, I find that one of the greatest challenges of writing a powerful short film is working with one’s limitations and compressing action to minimal locations to stay on track. How did your writing process keep the characters grounded in the driving lesson as a metaphor for the power dynamics and conflict in the couple’s relationship as the center of the film?

SK: I knew it’s more difficult to make a short film, especially after the feature. So, I just started with the idea: Let’s have fun and be as mad as the characters while making the film without any expectations. So, it was an awesome surprise first to be selected in Sundance, then the Grand Jury Prize. It reminded me of the first reason why we make movies: To have an amazing, fun time with the actors and the crew while telling our stories. Driving in the film is not only about driving a car in the film. It’s about adapting in a new society, about finding new roles; about women finding their voices, even in later stages of life. So, the basic idea was simple: The first part, he will teach her how-to-drive in darkness. The second part is that she is driving outdoors. Between the two locations, the characters will change and their relationship’s dynamics. They need each other after they lost everything, but they can’t continue in the same way as before.

NK: Your film plays with subjectivity in an unusual manner, especially when the act of the couple’s driving through the cityscape is repeated from two different vantage points as they survey their surroundings behind the wheel of the car. Can you describe your intent behind this decisive moment in the film?

SK: The film opens with the act of acting. Are we driving or are we acting that we are driving? It was logical for me to end the film with the need of the characters to continue the play, the acting, and the imaginary game. It’s the repetition of the game, the ritual of dreaming and creating a new reality that allows two human beings to continue their normal life after losing everything during the war. It’s their new utopia of a Syria that doesn’t exist anymore. It ends up with a vantage point like the vantage song of one of the most famous Syrian singers, Asmahan. The present of their city that they are longing for and creating doesn’t exist now, and looks already like the nostalgic imagination of a country like a beautiful utopia of a home that they won’t find.

NK: How did the theme of Syrian refugees become part of the film’s subtext? What did you learn tackling the nuances of the crisis against the backdrop of a low-key, domestic situation between a husband and a wife?

SK: I believe that the context affects even the simple normal acts of life (les acts quotidiens). As a Syrian in exile, I can’t myself write a story without this context. For me, the question isn’t about a low-key backdrop; it’s about how any domestic situation of a Syrian in diaspora will be once they are living this new reality: A refugee.

NK: What was your collaborative process like with your two remarkable actors? What did you learn from one another?

SK: The most difficult part was the casting, even for a short movie. I had two months of casting to arrive to those two amazing actors who are stars in the Arab region, too. I knew that this film is based on actors that can make the audience believe the simple story of driving a still car, so I didn’t want to compromise. Actors Abdel Moneim Amayri and Caress Bashar added beautiful layers to the characters, and one of the most amazing moments of the film is once Abdel was improvising in front of the car, and he looked to the void, remembering a real accident he had in Lebanon, a while ago, and he suddenly said “He looks like he is Syrian.” You need the collaboration of amazing actors that believe in the film to transcend the story to another level.

NK: What do you hope viewers will find as they sit shotgun with your characters in this most unusual driving lesson through the inner and outer landscapes of your conflicted characters as they reach out to one another despite their uncertain life and future?

SK: First, I want to thank you for the beautiful and thoughtful reading of the film. I’m really glad you felt this. For me, if the audience felt the same as you did in your question, or if they identified with the characters, and understand the struggle of being a refugee without stereotyping, it would be enough. Of course, it would be a great bonus if they really laugh while realizing it.

NK: What is next for you in your filmmaking practice? Do you have a feature-length work in the works and if so will it echo or expand similar themes and concerns explored in your short film?

SK: The main character in Aziza is inspired from the main character in the next feature-length fiction film project I’m preparing: Nezouh. I wanted to work on the same character and with the same actor to show the humor and dark comedy side of the character of being Syrian during the wartime. Readers once they read a story about refugees, they can hardly feel the dark, surrealist comic side of it until they watch it in a movie. And, somehow, you can only be a Syrian in a diaspora to feel the humor of it, the (Samuel) Beckett madness of it. As if being Syrian gives you the right to tell the story with humor while assuming and honoring the pain and struggle of being a refugee with authenticity.

SK: That’s why I feel grateful for the success of the short, hoping it will open new windows for the next project. It’s somehow the same madness. It’s the story of a Syrian who doesn’t want to leave his country, so no one can call him a refugee until his house is totally bombed and he is so blind that he couldn’t see it. So, he transformed his house into a big refugee tent. I needed Aziza to show how this tragic story has dark, surrealist humor in it.

NK: What advice do you have for other filmmakers creating short films in the trenches of independent filmmaking?

SK: It’s just have fun, take risks and break the boundaries. Short films are a beautiful reminder of why we first wanted to make films. Somehow, during the long struggle of making a feature film, we forget this.

Regions: Park City