New Directors/New Films 2019 (March 27-April 7)

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw selects 48th edition favorites at Lincoln Center and the Museum of Modern Art

If you like playing Ms. or Mr. First Nighter at the New York launch of filmmakers who’ll shape the future of cinema, ND/NF is your fest. Since 1972, first films and other early work by Pedro Almodovar, Sally Potter, Spike Lee, Kelly Reichardt, John Sayles, Chantal Akerman, Steven Spielberg, Marielle Heller, Todd Solondz, Charlotte Zwerin, Richard Linklater, Courtney Hunt, Wong Kar-Wai, Laura Poitras, Michael Haneke, Su Friedrich and Guillermo del Toro have been among choices that continue to unreel each spring on MoMA’s midtown screens as well as Lincoln Center cinemas on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

Coming up are 35 features and shorts from 26 countries, nearly half directed or co-directed by women. Eleven are by first-time feature filmmakers. The diversity is staggering. Your critic hunkered down to view everything available before opening night, and here are five favorites. None of these directors are household names—yet:

Clemency; Chinonye Chukwu; USA, 2019; 113 min.

Two years ago, the New York Film Festival chose the first documentary in its 54-year history as its Opening Night, Ava DuVernay’s 13th. Her doc powered deep into the 13th amendment to the constitution (“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States”) and its effect on incarcerated black men.

This year, the curators at the Film Society of Lincoln Center and MoMA have chosen Chinonye Chukwu’s chilling and often heartbreaking drama, Clemency, to launch the 48th edition of New Directors/New Films on March 27. It’s a movie that will open accompanied by its own real-life moment of clemency, an electrifying life-imitating-art-imitating-life decision by the governor of California that makes Clemency exactly the right movie at the right time.

The news was summarized in The New York Times lead editorial on March 14, headlined “A Pause for California’s Death Row”: “Gov. Gavin Newsom of California announced Wednesday that no executions will occur on his watch, granting temporary reprieves to all 737 inmates on the state’s death row. Mr. Newsom’s executive order also withdraws California’s lethal injection protocol, which has been mired in litigation for years. ‘I do not believe that a civilized society can claim to be a leader in the world as long as its government continues to sanction the premeditated and discriminatory execution of its people,’ Mr. Newsom said.”

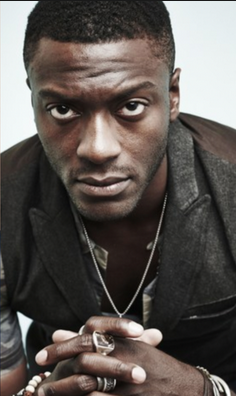

In the fiery script written and directed by Chukwu, this is exactly the dilemma that’s wearing down Bernadine Williams, the warden in a maximum-security prison. She’s played by the familiar screen veteran Alfre Woodard with a mix of dignity and desperation that’s new and fresh on a motion picture screen. This is a black warden who’s witnessed a dozen deaths, mostly of black men, and the most recent execution that opens the movie seems to take forever (see photo above). The attending medic can’t find the right vein, and the anguished man begins bleeding to death.

Chukwu goes to considerable lengths showing how warden Williams’s emotional reserves are being shredded by events like this. Besieged by constant protesters whose outdoor chants she can hear at her office desk, she’s become stand-offish to the media. We observe the strains in her marriage to Jonathan (Wendell Pierce, solid and empathetic), a college professor who shares passages from Ralph Ellison’s novel with his classes while privately lamenting “the empty shell” his wife is becoming in their marriage bed. Bernadine is drinking too much after work, both at home and in bars with her loyal assistant (Richard Gunn) who becomes her designated driver home. We’re caught in her slippery-slope nightmares in which she dreams she’s the one strapped down and awaiting a lethal injection.

The warden’s strict attention to daily ritual and procedure is counterpointed by the shrinking life of convicted cop killer Anthony Woods (Aldis Hodge), who’s been imprisoned through 15 years of appeals after an officer died trying to prevent a convenience store holdup. Woods admits involvement but denies he was the killer. His lawyer, Marty (Richard Schiff) is watching the clock tick down on unanswered pleas for clemency to the governor. This is Marty’s last case before retirement, and he’s all worn out by a justice system that’s awarded him too few victories.

As Woods maintains his innocence, the movie withholds recreating the holdup scene. Instead, director/writer Chukwu balances the cold fury of the slain officer’s mother (Vernee Watson, effective in a key role) who’s convinced Woods killed her son and is more than ready to watch him die, with a late-movie visit by Woods’ girlfriend (Danielle Brooks, equally effective) who’s always believed in his innocence. The warden’s job is carrying out a decision she had no part in rendering, as humanely as possible. She’s not judge or jury, but she’s the executioner. It’s a soul-crushing experience.

(The state in which Williams’ prison is located is not identified. Though it goes unspoken, it may dawn on you that unless the warden receives a last minute telephone call from the governor granting clemency, Woods will be the 13th prisoner to be executed on her watch.)

Alfre Woodard has been honing her craft since she stepped onto Joe Papp’s Public Theatre stage in 1977, in For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf. She’s piled up recognition, nominations and awards in Passion Fish, Down in the Delta, Miss Evers’ Boys, Steel Magnolias, The Practice, 12 Years A Slave, Crooklyn. At 66, Woodard can do anything, and one thing she does with supreme grace in Clemency is yield the screen to her volcanic young co-star, Aldis Hodge, whose work is acting the rage, fury, hope and exhaustion of a man sentenced to die for a crime he may not have committed.

Photo: Paul Sarkis

Whether he’s aimlessly circling a patch of ground bouncing a basketball, or methodically battering his head over and over against a concrete wall until the guards come running, Hodge does the movie’s heavy lifting with a brio that may break you even further than the warden’s reigned-in suffering. Their scenes together have a quality that occasionally lifts this movie into places more often found on the indelible pages of Ralph Ellison, but maybe that’s just one viewer’s blurry tears. This is Academy-level work.

“Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?” is the last line of Ellison’s towering novel, Invisible Man.

One footnote about Chukwu worth thinking about when you see her distinguished drama: She’s the founder of a filmmaking collaborative called Pens to Pictures, that teaches and empowers incarcerated women to make their own short films. In under three years, five films have been made in partnership between women in Dayton Correctional Institution, and artist communities in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Pennsylvania.

Clemency shows Wed. March 27 at 7:00pm and 7:30 pm at MoMA, and Thurs. March 28 at 8:00pm in the Walter Reade Theater.

Mexico Without Walls—The Rural Side, The Urban Side

Last fall, Alfonso Cuaron’s Roma was instantly perceived by cineastes as a pioneering New York Film Festival selection—maybe the best in its 55 years of dramatizing the mutual interdependence of the rich and the poor. Roma is Cuaron’s partially autobiographical cine-memoir, inspired by his own professional family and its indigenous caregiver/housekeeper. Shot in a subdued wide screen black-and-white and set in a pre-Internet Mexico City, it was both epic in its dramatic sweep yet timeless in its poetic intensity. Ironically, its 65-mm panoramic splendor and intricate Dolby Atmos sound mixing is now being streamed to the world’s devices and ear pods. This undeniably lessens their Oscar-winning impact—it will never be an ideal airplane movie. But one in this festival is:

Fausto; Andrea Bussmann; Mexico/Canada; 2018, 70 min.

Read any good movies lately? The best reading in this fest is Ms. Bussmann’s 70-minute anthology of short stories. It would make the perfect reading if you’re flying, say, from New York to Washington D.C., because you wouldn’t want to look up from the subtitles, and even if you did, the visuals are rarely more than a framing device for the text.

(storytelling locales of Fausto)

Bussmann is a 39-year-old Canadian writer/producer/director/cinematographer/editor. She has two master’s degrees, one in social anthropology, the other in film production. She lives in Manhattan with her husband, who is Mexican, and when they vacationed on the coast of Oaxaca, she brought along a Sony A7 and an out-of-the-box concept: using Faustian mythology as a metaphor for folkloric Mexican tales. Everyone is a bite-sized, one- or two-minute gem, and here’s one example from what’s become her first feature film:

“Ziad works for Alberto translating documents. But now he is making a map for him. This has been a particularly difficult task, as the coastline is constantly shifting. While they won’t say what the map is for, I know they are looking for a shadow. A young Frenchman came to this place, and asked to stay in exchange for his labor. Intrigued by his charm and beauty, they accepted his offer with one condition, that he leave something behind for them. He agreed to leave them the only thing in his possession, his shadow. After several months he left them. …When the moon is bright, they look for his shadow.”

ocean in Fausto

The search for the shadow leads them to the various townspeople, among them a one-armed zookeeper. He only comes to town at night, explaining that he’s afraid of his shadow. The shadow of the zookeeper’s missing arm appears at random. Shadows, you see, are “uncontained memories.”

This tale starts another. All the zookeeper’s animals are blind. and only make noise at 4:00 am. They can sometimes be seen and heard on the beach, in a deserted place called The Enchanted House, which is cleaned regularly and where a gorilla was once seen banging on a bedroom window. As the animals are blind, there is no need for cages. They’re nonjudgmental, and pose no threat to local authorities.

What you’ve read above are stories segueing into stories. The reality today, the narrator insists, is different: soldiers patrol the beaches and jungles at night, looking for drug traffickers. They used to only kill animals when their safety was at risk. But soon they discovered rare specimens could bring top dollars on the black market. So, they kill animals and bring them to The Peruvian, who runs a silent zoo deep in the mountains. Silent zoos exist everywhere, even among stuffed animals, even in dioramas at the Museum of Natural History in New York City. And by petting or studying these animals, one can receive messages from the future. Blind animals are the most telepathic of all.

This questionable narrator, as you suspect, may be yet another gentle weaver of stories. Along Bussman’s vacation beach, people like the zookeeper become stand-ins for Faust, for a devil “with dark eyes, a piercing gaze, a malicious smile.” The few people we actually see on the picture-postcard sands are either grizzled expats who look like they’ve wandered out of tropical novellas by Joseph Conrad and Somerset Maugham, or natives engaged in endlessly shoveling sand into makeshift dykes to push back the sea. But the ocean keeps flooding the dykes. Like the young Frenchman in the first fragment, the workers and other natives we’re shown are figures in a fluid narrative, sometimes posing as the devil’s victims. Like Faust, they’re “trying to unlock the keys to the universe and themselves.”

Bussman notes that when people vacation along Oaxaca, their computers often stop working. The power will be on, but the screen remains black. The sand, she explains, is full of iron, which is why the beach has a black tinge. The iron also produces “physical alterations” which she doesn’t elaborate on. Artificial lights are banned on the beach, because it’s believed lights confuse the turtles and prevent them from finding their way back to the sea. Are you taking notes on all this?

Heady stuff, the fabled rural side to a Mexico without walls. Fausto shows Sat. April 6 at 3:45pm at the Walter Reade Theater and Sun. April 7 at 1:00pm at MoMA.

Midnight Family; Luke Lorentzen; Mexico/USA; 2019, 81 min.

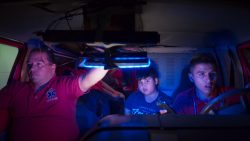

The urban side to a Mexico without walls is a documentary taking place in today’s Mexico City. It’s a reality check of the first order, for the local government operates fewer than 45 emergency ambulances to serve a population of nine million. Thus a loose system of private ambulances has taken over much of the city’s emergency healthcare.

Writer/director/cinematographer/editor Luke Lorentzen shows how a father/son paramedic team, Fer and Juan Ochoa, barely eek out a nighttime living hauling the city’s sick and injured to hospitals in their gleaming red MED CARE ambulance. The brains of this outfit appears to be 17-year-old Juan, who’s administering first aid to a gunshot victim. He’s enormously likable. It’s a startling reveal that will hook any big city dweller instantly.

The Ochoa unit functions like a well-oiled machine. Radio dispatchers broadcast the location and code the emergency situation. Juan is the driver; Per is on a squawk box ordering taxis and busses to clear the way. (A younger son, 9-year-old Joeuv, whose job is cleaning and polishing the family ambulance, tries to stay strapped in back as the vehicle speeds and careens to its destination.) The city is vast and even at midnight many of its boulevards are filled with traffic.

Most city ambulances came off the assembly line in 2006 or before. Chances are the Ochoas will beat out a city ambulance to the victim. If the Ochoas make the pickup before their independent competitors, and if the victim has money to pay for the transport, Per and his family scrape by another day. This is largely a poor-serving-the-poor operation, and when Per tells Juan a victim had nothing to offer them but gratitude, both father and son understand.

An urgent transport is billed at 3800 pesos (around $200). Somehow the Ochoas go on paying for stretchers, medicine, bandages, splits, oxygen, saline solution, neck braces, uniforms, gas, oil, and the occasional bribe. (The mother, whose day job is not defined, doesn’t look thrilled with any of this.) We observe the ambulance running out of gasoline—it has to be pushed into a service station. The family has learned to skip a meal. The men sleep on the floor in a simple apartment.

Papers are demanded by the police, who frequently pull over and check paramedics for proper plates and “protocols.” Private ambulances can be impounded. We recognize Mexico City is stuck with another gummed-up administration. Instant decisions have to be made, sometimes with the victim’s consent, whether to drive to a government hospital or a private facility. Many citizens have no medical insurance. Often government hospital emergency entrances and waiting rooms are clogged and filled.

Per’s role here is to provide comfort to the victim. He’s very good with blankets and hugs. Per does all this knowing that a broke, stoned dad with an unconscious infant can’t be turned away, nor can a daughter who’s fallen four floors and is laying on the pavement with a critical head injury.

Lorentzen’s production is smart, sharp and assured. It’s an earnest, no-frills examination of an empty pockets occupation that seems both doomed and vitally necessary, sometimes in the same breath.

Midnight Family shows Thurs. April 4 at 8:30pm at MoMA and Fri. April 5 at 9:00pm at the Walter Reade Theater.

Two Turkish Delights

There was a time when finding one outstanding Turkish film in ND/NF would have been a true rarity. This year there are two—the best evidence, as with the two Mexican selections applauded above, that filmmaking is growing by leaps and bounds, worldwide. It helps that Manhattan and surrounding boroughs have well over 50 indie screens to showcase the surge. A continuing shout-out to Richard Pena, who spent a quarter century running NYFF and ND/NF festivals, digging out what was new and exciting in ancient spots like downtown Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir.

Honeyland; Tamara Kotevska and Ljubomir Stefanov; Turkey, 2019; 85 min.

In the opening seconds of this beguiling doc, a creased woman of 55, followed by the camera, makes her way slowly, cautiously, along the side of a sheer mountain outcrop. The wind is howling, the siren-y music is grating, where are we this time and what is this poor soul searching for? With calculating care, she removes a chunk of rock, exactly fitted to conceal wooden frames holding thousands of clinging bees, all calmly hovering. Her head covered, she scoops cones of bees into her basket and makes her way back down to her isolated stone-and-earth home in a valley. This is Hatidze Muratova, surely the one woman in a primitive landscape who’s making her living as a solo beekeeper.

Hatidze wails and chatters to the bees. She passes her hands through them. In her spartan home, she feeds and attends her mother who’s 85, blind in one eye, bedridden. Mom believes she is becoming a tree. She tells her daughter she’s not dying, just “living to make your life miserable.” Outside, Hatidze rescues more frames, coated with honey and layers of bees. Crooning away, she siphons off half the honey she’ll take to market and sell. The rest stays with the bees to insure their sustainable future.

On the bus heading to Skopje, the largest city in North Macedonia, we glimpse a teen, who neither she nor the filmmakers are paying any attention to, who’s sporting a mohawk. In the market, which is startlingly contemporary, Hatidze demands 16 euros for a jar “straight from the beehive, with honeycomb, pure and unsugared,” from the merchant, who is Bosnian/Albanian. She settles for 10 euros a jar. (At an outdoor flea market, she seems to do better.) Hatidze shrewdly barters her way along the stalls, picking out a chestnut hair color, (both mother and daughter color their hair), bananas, a peacock’s tail that’s been shaped into a fan to wave the flies away from mom.

One day a flatbed truck arrives and unloads a house trailer, tractor, husband, wife, chickens and unruly children galore. They grow corn and raise cattle who immediately roam into Hatidze’s outdoor honey land. Maybe this is how it works in rural Macedonia—migrating Turks move in and unload all they own, then throw up a tin roof shelter. Hatidze keeps a wary eye on these interlopers, though she makes friends with the children. But she makes a mistake in sharing her beekeeping and honey making secrets with the father, who obviously views his next-door neighbor as a bag of money. Urban as well as rural viewers worldwide will sigh, recognizing this cagey dad and his brood as the proverbial neighbors-from-hell.

Sure enough, Hatidze finds she’s inherited a second-class competitor and a first-class headache. The father’s in this for all the honey he can produce and sell. Even his children recognize their dad as a honey thief. The kids get stung repeatedly. The family sells too early in the season, causing combs to collapse. Finally fed up with her neighbors as the riffraff they are, Hatidze tells the father to pack up and get out. He responds by setting their surrounding grasses on fire.

As documentarians, Kotavska and Stefanov realize they’ve stumbled on a doozy of an ethnographic set-to, and they let it play out. They’ve built a mini-classic of how territorial imperatives still exist in lands without borders or fences. Their first-rate production is steady and confident. Best of all, Hatidze and her mom, like the paramedics in Mexico City, are wily survivors with good hearts. They have the will to carry on with their labor and their honesty, and we never doubt they will.

Honeyland shows Wed. April 3 at 6:15pm at MoMA and Fri. April 5 at 6:30pm at the Walter Reade Theater.

Belonging; Burak Cevik; Turkey, 2019; 72 min.

If you’re watching two dozen movies, one after another, in an esoteric film festival, it’s easy to stumble and get lost. Sometimes that’s part of the fun—getting wrapped up in the sleek mechanics of filmmaking in some far-flung land, not having a clue what you’re staring at, or what any of it means. Such films usually end up in a “sorry, not reviewing” pile. Your critic does this with too many pictures he watches. But then a sleeper comes along that hits a nerve.

Consider Belonging, which for over 27 minutes is a narrated letter supposedly written by the director to his aunt. Let’s call him Onur, as he’ll eventually be seen, played by Caglar Yalcinkaya. He’s seeking the aunt’s permission to weave his tale. A lot of it’s going to play over a black, blank screen. You think you’re going to listen to and read another 70-minute airplane story, not unlike the tales in Fausto.

Onur explains his new film looks like “an ordinary tragedy.” He claims he’s obsessed over themes like death, dying and killing. The tangibles are an autopsy report and a police interrogation report, cellphone and text messages, a pharmacy receipt for a drug, plus a DNA test he says his mother had waited for months to receive. And “the moment you were taken by the cops,” whatever that means. That’s when we first see the young woman, Pelin, acted by Eylul Su Saplan, but only once, as his story begins.

He tells us he’s in his 40s, born in Mersin, a son of teachers, and went to work at Mersin University in 1996, served in the military as an accountant, and met Pelin at the Mystic Cafe. They had a long, lonely talk through the night—we’re aware we’re watching waves buffeting a shore, just like at Oaxaca off the Mexican coast in Fausto. She takes Onur to her home and beds him. We see their neat, airy twin bed made up in the morning. They separate for four months while he does Army duty. She leaves messages and they reunite. She goes to his house in Izmir. There’s a quiet electronic hum moving onto the soundtrack. Maybe this story’s going to turn into a movie. Not yet.

The couple decide to marry. Their parents meet and become friends. Onur goes to a large hotel which he calls “the crime scene-to-be.” Pelin tells him she’s trylng to get her ex-boyfriend to murder her mother. When Onur pooh-poohs all this, Pelin begins to distance herself from him. Both are despondent. He thinks about suicide. We see distant views of a grey, grim shoreline.

Onur throws away his mother’s wedding ring, which he’d planned on giving to Pelin. She offers to reunite if he kills both her parents. They consider Laroxyl (sleeping pills) plus giving her parents fatal heart massages. Onur decides to hire a chap, Recep, to give the massage, thinking he’ll kill Recep after the parents are dead. Pelin mails Onur her parents’ house keys, with a note confirming “I won’t regret this.” She arranges to put the pills in her parents’ tea. Later she calls to report they’re falling asleep. Onur gives Recep the keys to her parents’ apartment. But the door has jammed and he can’t get in. Onur comes up and discovers Pelin’s mailed him the wrong keys, and her phone is off. The two men manage to wedge the door open but a chain lock is on. We’re watching many of the objects described in red-tinted closeups, never the people. Then Pelin’s father awakens and the men beat a retreat.

The next morning Recep decides to try again, with Pelin’s urging. The father has gone out. Onur goes up shortly after Recep, finding Recep and Pelin’s mother covered with blood. Bent knives and a rod indicate a terrible struggle has occurred. The mother is dead. Onur flees with Palin, and the two travel separately by bus and car to Ankara. (Objects but not people are shown.) We’re beginning to feel like this might become a Turkish neo-noir. Palin’s brother-in-law phones to report her mother’s death.

27 minutes in, the opening title credits appear over a lush love song, and a Turkish neo-noir does begin. As they used to say in Hollywood, if you’ve read the book, you’re ready to watch the movie.

And so we do. Now get this—it’s an expanded adaptation of the first ten minutes of the story we’ve been listening to for nearly half an hour. Plus a few flash-forwards too neat to reveal.

Love it!

Belonging shows Thurs. April 4 at 9:00pm, at the Walter Reade Theater, and Fri. April 5 at 6:15pm at MoMA.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s choices at the Tribeca Film Festival, April 24-May 5.

Regions: New York City