New York Film Festival 2019 – Critic’s Choices

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw salutes favorite dramas, docs and shorts in a festival top-heavy with violence

You’d need a breather, if not a medal for bravery, if you made it through all 15 law-and-disorder crime dramas that ricocheted through NYFF’s 57th annual festival. Imagine, fifteen features—that’s over a day of murders before your blinkered eyes. Bookending the mayhem were Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman, the opening night epic of Jimmy Hoffa’s assassination by a trusted Teamster associate, and Edward Norton’s Motherless Brooklyn, the closing night tale of a 50’s gumshoe with Tourette’s syndrome mired in New York City corruption.

Three other main slate selections escalated their varying tensions into lengthy slaughterfests—Bacurau, an uneasy Brazilian tale of a rural town besieged by murderous mercenaries; Saturday Fiction, a black-and-white Chinese thriller about a Shanghai theatrical troupe falling to pieces on the night before the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor; and Parasite, a stinging South Korean satire in which a crafty lower depths family infiltrates the home of a rich but hapless family preparing a birthday celebration—a backyard party that begins the body count before the cake is sliced.

Then there’s The Moneychanger from Uruguay, in which a dapper-but-dopey currency manipulator watches his risky behavior go off the rails…The Wild Goose Lake, a take-no-prisoners Chinese escapade with a femme fatale ducking rival gang’s bullets…Marco Bellocchio’s The Traitor, a masterly biopic of Cosa Nostra boss Tommaso Buscetta that’s meant to be weighed and compared with The Irishman…The Whistlers, the first true Romanian neo-noir procedural (with four American producers) about a morally ambiguous detective who travels to The Canaries to learn tribal whistling, the movie’s title branding device…and Oh Mercy!, another taut procedural with this fest’s singular standalone good guy, a French/Algerian police chief in gritty Roubaix who solves the murder of an elderly reclusive.

Wait, there was more in NYFF categories outside the main slate of 29 features viewed for consideration. One Special Event was the 139-minute restoration by Francis Ford Coppola of his star-encrusted 1984 Harlem drama, The Cotton Club (with nine added minutes), focused on Dutch Schultz’ influence on the Harlem numbers racket in the Depression era.

Wait, there was more in NYFF categories outside the main slate of 29 features viewed for consideration. One Special Event was the 139-minute restoration by Francis Ford Coppola of his star-encrusted 1984 Harlem drama, The Cotton Club (with nine added minutes), focused on Dutch Schultz’ influence on the Harlem numbers racket in the Depression era.

Another was Joaquin Phoenix’s memorably murderous turn as Joker, also starring all-smiles talk show host Robert De Niro, who makes the fatal mistake of inviting him as his late night guest. And as its annual ‘secret screening,’ the Film at Lincoln Center curators unveiled the Safdie Brothers’ Uncut Gems, with Adam Sandler as a frazzled midtown diamond dealer in over his head with racketeers.

Finally, as if too-much-violence-wasn’t-nearly-enough, NYFF’s Retrospective section offered a trio of classics baked in evil: Gene Tierney’s unforgettable Technicolor turn in Leave Her To Heaven (1945), quietly sitting in a rowboat, coldly watching a struggling youngster drown… He Walked By Night (1948), in which Richard Basehart’s cop killer is captured in film noir’s inkiest blacks ands whites by ace DP John Alton…and Coppola’s Oscar-winning The Godfather: Part II (1974), with Gordon Willis’ lushly atmospheric cinematography framing De Niro and Pacino on their way to becoming the legendary stars of 2019’s Opening Night.

It seemed that what goes around came around in the world’s most closely watched film festival. We begin this set of critic’s choice reviews with three of this viewer’s crime favorites, looking at the first two together:

The Irishman; Martin Scorsese; USA, 2019; 209 min.

The Traitor; Marco Bellocchio; Italy, 2019; 165 min.

Robert De Niro plays Frank Sheeran, the obedient foot soldier, disciplined enforcer and WWII combat-trained killer who grows into the top associate of Teamster president Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino, still volcanic after all these years) as well as his godfather, mob boss Russell Bufalino (a mesmerizingly quiet and serpentine Joe Pesci). De Niro shapes his performance as a rank-and-file working man who drove a meat truck for Food Fair, siphoning off chickens and sides of beef, rising to become a respected and feared Union leader. He endured over a year of combat in theaters of war, sharpening his skills with weapons.

In The Traitor (Il traditore), Pierfrancesco Favino plays Tommaso Buscetta, another dedicated foot soldier who maneuvered and killed his way to the top of the Sicilian Palermo mafia during its struggles for control of the international heroin trade in the 1980s and 90s. Buscetta claimed to be an “agricultural businessman” but was a savage and unforgiving capomandamento.

Both were much-married men with children. Buscetta revealed most of what he knew about the crime syndicate he headed to a trial judge who won his trust. Sheeran never ratted out other killers or himself in court, but confided nearly all of his climb to ill-gotten fame to author Charles Brandt. (His book I Heard You Paint Houses, devotes hundreds of pages to Frank’s ascent and immersion in mob rubouts and mob speak (“paint houses” means carrying out execution orders). Sheeran confessed 25 mob hits to the author. Both Sheeran and Buscetta served prison terms but managed to pass away peacefully in 2000 and 2003.

Each film is a career high for its master director, Bellocchio at 79 and Scorsese at 76. Both movies are dense, handsomely layered and tell reasonably accurate tales that move backward and forward in time, illuminating how crime syndicates operated in Italy and America in the closing decades of the last century. But The Traitor is looking lonely and under appreciated at the moment, nearly lost in the long shadow of The Irishman’s extravagant budget, de-aging effects hoopla and pre-Oscar buzz.

If you watch both movies, you’ll be conscious of the the same elements—pride, greed, jealousy, betrayal, revenge, confession—arranged by artists who know how to build and sustain historical dramas that work big time on screens worldwide. One significant difference between The Traitor and The Irishman, which will become more apparent long before the 2020 Oscars, is that Scorsese’s film, financed and distributed by Netflix, has an initial release limited to November, while Bellocchio’s work, distributed by Sony Pictures Classics, should enjoy long-term availability in art cinemas.

This is an advantage for The Traitor because its opulent Saint Rosalia celebration, lush Rio de Janeiro villas, spectacular bridge and highway rub outs—all play bigger and more memorably on the big screen. So do courtroom scenes ablaze with dozens of Cosa Nostra mobsters in barred cells flanking the judges’ benches, who scream threats at witnesses testifying in bullet-proof glass boxes. These latter scenes covering six years of Maxi Trials are an astonishing setting, loud and combustible—there wasn’t much decorum in Italian courtrooms.

One vivid history lesson that emerges through Buscetta’s journey through two decades is that mob manners changed overnight when smuggling contraband cigarettes was replaced by trafficking in heroin. As the profits soared, courtesies like holding off whacking a member of the Corleone rival clan who always walked with one of his children in his arms or in front of him, began to disappear.

Like his American counterpart Frank, Bellocchio’s Tommoso believes in codes of conduct, honoring commitments and respecting an enemy’s family. He’s also pleasantly vain, dying his graying hair and smoothly delivering a ballad to an adoring crowd. But when two of Buscetta’s sons and his brother-in-law are mutilated and slain by competitors, along with his trial judge Giovanni Falcone (an empathetic Fausto Russo Alesi) who Buscetta has unburdened himself to, The Traitor becomes a bitter revenge saga. Falcone’s horrific demise in his car following an explosion that collapses an entire bridge is a jaw-dropper—it rivals and may exceed any kill scene you’ve winced through in a Scorsese film.

This feisty and opulent drama is a compelling followup to Bellocchio’s 2009 Vincere (also a Cannes selection), just as The Irishman is a fitting followup to Scorsese’s Oscar winning mob epic, The Departed. Both pictures use disarming devices to keep track of all the mayhem on screen—Scorsese supers informative titles on who went down when, Bellocchio supers a ticking clock before major hits. Both are unrelievedly dominated by men. (Maria Fernanda Candido contributes a few telling moments as Buscetta’s third wife, while veteran pros Anna Paquin and Marin Ireland as Frank’s daughters make the most of their mostly silent, fearful moments with their father).

One of the truly startling similarities between the two movies is the casting of Nicola Calli as Toto Riina, Bascetta’s arch rival and the quietly sinister “boss of all bosses,” along with Joe Pesci’s casting as Bufalino, a similar top-of-the-world mobster, who grows light years as an actor by giving up nearly all the bombastic schtick he’s famous for on the screen. Pesci delivers so much more by delivering so much less. Look at these two criminal masterminds in side-by-side scene stills—they could be brothers.

The delicious music scores in both pictures are, no surprise, in the seasoned hands of Scorsese and Bellocchio regulars— Robbie Robertson, who’s given fresh new life to Muddy Waters’ classic blues and a slew of familiar period tunes in his 11th Scorsese collaboration…and Nicola Piovani, who brings operatic sweep and grandeur starting with Nobucco’s signature “Va Pensiano” in his 7th Bellocchio collaboration. And surely a prime reason The Irishman never feels too long at three and a half hours is due to its peerless editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, who been at Scorsese’s side through 20 feature films starting in 1967. She’s won three editing Oscars (for Raging Bull, The Aviator and The Departed), and at 80 may have earned her fourth.

As may have Steven Zaillian, whose adaptation of I Heard You Paint Houses sticks like Elmer’s Glue to Brandt’s factual summaries of who/what/when/where and why, intercut with Sheeran’s narratives. Zaillian doesn’t disguise the hatred both Hoffa as well as Bufalino felt for President John Kennedy and especially Attorney General Robert Kennedy, who went to work on organized crime like a shovel nose on shrimp. The Kennedys decimated much of the mafia empire through Bobby’s ‘Get Hoffa Squad.’ The film includes Bufalino’s ominous line, “If they can knock off a president, they can knock off the president of a union.”

A Q&A press conference on the morning of the picture’s premiere, September 27, included a reviewer’s query on the book’s detailing of Sheeran’s recollection “carrying a duffel bag of high-powered rifles” to Tony (‘Tony Pro’) Provenzano, a Genovese captain who ran a Teamsters Local in north Jersey. This was two days before Dallas. Before and after Sheeran talked about the rifles, he told Brandt he couldn’t talk about Dallas. Brandt’s book ends rife with unexplored conspiracy theories. Scorsese, in the Q&A: “You can interpret the Bufalino line, if you want, meaning ‘they’ knocked him off, we didn’t knock him off…but people can be taken out.”

Should you give six hours of your time to somewhere, somehow watch both The Irishman and The Traitor, knowing how distressing yet how hugely entertaining each is? Without question.

Oh Mercy!; Arnaud Desplechin; France, 2019; 119 min.

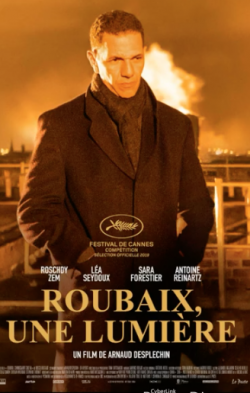

The French one-sheet for Oh Mercy!, pictured here, defines this absorbing, fine-tuned procedural instantly. It’s set in present-day Roubaix, an austere and hardened northern city near the border of Belgium. The screenplay by Lea Mysius and Arnaud Desplechin, who was born in Roubaix, tells us “many middle-class homes have been abandoned, 45% of the population lives in poverty and 75% of its neighborhoods are no-go zones.” The original French title, meaning “Roubaix, a light,” is properly self-defining and tinged with irony, since Desplechin’s drama begins on Christmas Eve and many scenes take place at night.

Roubaix is also where Yacoub Daoud, the Algerian police chief played by a rock-solid Roschdy Zem, was raised from childhood and has remained. He dominates the poster as well as the movie. (The picture’s present title, Oh Mercy!, is a confusing non-sequitur.)

Its first hour is devoted to demonstrating how thoroughly captain Daoud maintains a close, hands-on presence in everyday police matters—breaking up a Christmas dinner slugfest, investigating a car set on fire, checking for signs of arson in a burned-out building, taking on the task of locating a missing teen and bringing her back home. Daoud grew up and and still knows many local residents. He delegates authority confidently to a loyal and admiring staff. He lives alone (his family except for a jailed nephew has moved back to Algeria) but feeds stray cats and has an abiding love for horses at the local race track.

He’s this festival’s one lone, likable justice figure, a true establishment hero, and we feel both secure and comforted in his presence. We’re primed for the grim central precinct he polices to turn up some awful new crime.

Desplichen doesn’t disappoint. An 83-year-old woman is found strangled in her bed. Daoud and his staff, including an up-and-coming young lieutenant, Louis (Antoine Reinartz, agreeably eager) begin interrogating young and old around the scarred neighborhood. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, suspicion begins to fall on a young lesbian couple who live close by. This is the picture’s McGuffin. Acted by two powerhouse women in their early 30s— Lea Seydoux (as Claude, a single mom) and Sara Forestier (as Marie, a lost soul on welfare)— this story device lights up the screen like gangbusters through the second hour. But not as we might expect.

Both women deny any involvement to captain Daoud. They point out faces in police files they say were prowling the neighborhood. But the alibis of these folks all check out, and little by little the chief gets hunches about this young couple. He wants to coax deeper feelings from Marie and Claude, events that could alter their memories and and even their taped depositions. We start to wonder: Is it possible we’re watching a slow, steady, drip drip drip dissolution of a love affair? Both women grow increasingly wary, shape-shifting their relationship into what Marijane Meaker, one of the two living legends of early lesbian fiction, titled her second novel in 1958: The Evil Friendship.

This is heart rending territory for a modern-day lesbian partnership. Seydoux and Forestier make it a master class in how each woman clings to self-willed innocence…but will it mean sacrificing her partner? Mercy is about the last thing Oh Mercy! has on its mind in this riveting tale out of Roubaix.

Beanpole; Kantemir Balagov; Russia, 2019; 130 min.

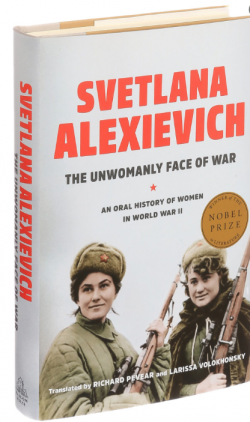

The woman in hospital garb staring off into space is a cinematic portrait of The Unwomanly Face of War. That’s the title of Svetlana Alexievich’s remarkable collection of interviews with over 200 enlisted female soldiers—a cross-section of the million women who enlisted in the Red Army serving Russia during the Second World War. They were pilots and tank drivers, nurses and doctors, snipers and anti-aircraft gunners like Iva, played here by a tree-top tall newcomer, Iya (Viktoria Miroshnichenko), known to everyone in the Leningrad veterans’ hospital in which she’s a nurse/patient as “Beanpole.”

Balagov was captivated by these women. Author Alexievich researched her oral histories starting in the late 70s with war and labor camp survivors. The book first surfaced in Russia in 1985, heavily censored by the Soviet regime; its unexpurgated version, published by Penguin in 2017, won the Nobel Prize for Literature. The interviews reveal that most enlistees went to war as patriots ready to engage the enemy just like their male counterparts, dreaming they’d emerge victorious, perhaps with the ideal serviceman in tow to love and marry. The following excerpt summarizes the tragic realities of war—it mirrors the concept of director Balagov’s grief-laden drama, easily the most profound and memorable motion picture shown in this festival:

“Whatever women talk about, the thought is constantly present in them: war is first of all murder, and then hard work. And then simply ordinary life: singing, falling in love, putting your hair in curlers. In the center there is always this: how unbearable and unthinkable it is to die. And how much more unbearable and unthinkable it is to kill, because a woman gives life. Gives it. Bears it in herself for a long time, nurses it. I understand that it is more difficult for women to kill.”

From its opening moments, Beanpole doesn’t look well. She’s distracted, slow on the take, subject to seizures, suffering with the traumatic stress of PTSD. Director Balagov, aided by a Russian translator, explained to an audience at Lincoln Center that his language’s equivalent of “beanpole” (dylda) has nothing to do with height, but instead means clumsy, signaling how difficult or impossible recovery was for those who survived the horrors of WWII.

The movie confirms this once, when we observe a crowd gathering around a person who’s fallen, or attempted suicide, under a train. Passersby refer to the victim as a “beanpole,” and we assume it must be Iya. But it’s not. History tells us over a million Soviet citizens perished just in the Nazi German and Finnish invasion of Leningrad. Death came cheap in a city in which, as one patient observes, “there are no dogs, they’ve all been eaten.”

As you may sense, Beanpole the movie is full of trapdoors. Initially we assume the tiny Pashka (Timofey Glazkov, a sweetheart find) is Iya’s son, but that’s not right, either; she’s just caring for him. He actually belongs to Masha (Vasilisa Perelygina), a fellow combat veteran sporting red hair, who despite recurrent nosebleeds seems more alert, more sexualilzed and increasingly more calculating. Iya will shortly tell Masha the movie’s most poignant lie, that her child died in his sleep.

And Masha will move on, without mourning, hauling along Iya in a wintry night in Leningrad to dance and maybe find a soldier or two to seduce. Having lost one child, she’ll try to have another. The women pair off with two young guys, and Iya’s date returns with a broken arm. But Masha seduces her young charge —he’s courteous, well-spoken, and looks for all the world like a post-teen Vladimir Putin. Masha sets wheels in motion to eventually meet his wealthy parents at their country mansion, and marry the kid.

This plot is doomed to fail, too. So is Iya’s willingness to become a surrogate carrier for Masha—the women engineer the hospital’s older doctor, Nikolay (a weary Andrey Bykov) into having a night’s intercourse with Iva, thinking he’ll impregnate her. But she doesn’t conceive. The women are left to try and make new lives, perhaps together, perhaps not.

Beanpole at once joins the ranks of cinema’s most indelible antiwar pictures, simply for its fixed gaze on two female victims of war. It boasts a meticulous production design that re-creates 1945 Leningrad—its streetcars, food rations, failing electrical systems, listless crowds, with finite skill. Kseniya Sereda, age 24, is DP, shooting a 28-year-old director’s sophomore feature. Her cinematography gives this old-world drama a pristine, slightly muted feel that’s impeccably color-coordinated and ravishing in its sadness.

“Clumsy” is perhaps too harsh a descriptive for the two wartime warriors who anchor this unforgettable movie. “Bent but not broken” might be more accurate.

Marriage Story; Noah Baumbach; USA, 2019; 136 min.

When a theater is packed and the movie is truly enthralling, people still lean in. Rather, they lean forward to get closer to the image, to better absorb some infusion of magic up on the big screen. In New York Film Festivals, it most often happens in documentaries about movies, like Bertrand Tavernier’s A Journey Through French Cinema, or this year’s delightful Varda by Agnes, which includes a scene from her 1995 One Hundred and One Nights, in which guest star Catherine Deneuve takes a boat ride with Robert De Niro, who’s only starring in three other major motion pictures in this festival. De Niro never stops building his craft, just as Ms. Varda did through 90 years.

When a theater is packed and the movie is truly enthralling, people still lean in. Rather, they lean forward to get closer to the image, to better absorb some infusion of magic up on the big screen. In New York Film Festivals, it most often happens in documentaries about movies, like Bertrand Tavernier’s A Journey Through French Cinema, or this year’s delightful Varda by Agnes, which includes a scene from her 1995 One Hundred and One Nights, in which guest star Catherine Deneuve takes a boat ride with Robert De Niro, who’s only starring in three other major motion pictures in this festival. De Niro never stops building his craft, just as Ms. Varda did through 90 years.

One reason the NYFF curators may have chosen Marriage Story as its “Centerpiece” presentation is that it’s the one story with a bi-coastal New York couple—bright urban sophisticates wrapped up in theater who’ve also been wrapped up in each other and their button-cute son for years—who suddenly split down the middle. Why didn’t their center hold? What happens when one marriage tale becomes two divorce tales? That’s the juicy, tantalizing mystery writer/director Noah Baumbach, who understands divorce as well as any Manhattan dad, invites you to investigate.

Next to discussions on spiraling residential prices and escalating school tuitions, the one conversation many Manhattanites will lean forward to eavesdrop on (almost anywhere) are the strategies and costs of getting a he-said-she-said divorce on the East Coast vs. the West Coast. Baumbach’s screenplay rolls out mountains of due diligence—hard, of-the-moment info on the nuances of child support, alimony, custody factors, residential requirements, spousal behavior (including adultery and drinking), distribution of assets, personal property, communal property, lawyers’s fees and on and on.

His original screenplay, an Oscar shoo-in, practically enrolls you in a white shoe, class-of-2019 law school. It’s a pitiless, take-no-prisoners primer for couples who’ve gone through, or are thinking about, splitting. And in its funny, ghastly complexity, his screenplay may be a cautionary warning sign of such monstrous magnitude, that many couples will sigh on the way home and secretly conclude it’s far easier (and far cheaper) to just stay married. Netflix, the distributor, is betting Marriage Story’s potential home audience is most of wedded America.

All the legal beagle fine print wouldn’t make a glowing festival centerpiece without a knockout cast conjuring up a lot of magic, and Marriage Story boasts five performers—an ensemble company cast to perfection— you can’t stop leaning forward to admire. Charlie (Adam Driver) is the Brooklyn-based theatrical director who’s ready to move his downtown Manhattan production of Elektra featuring his wife, Nicole (Scarlett Johansson) to Broadway, as she’s about to serve their divorce notice. For her part, Nicole has just accepted an offer to shoot a tv pilot in LA, where she was raised, and is preparing to move their 8-year-old son, Henry (Azhy Robertson) along. We’ll register she’s walking away from her Broadway debut.

Baumbach plants a few more clues for their breakup: This is Charlie’s turning point as a theatrical director (he never watches television) who’s about to realize a lifetime dream of bringing a classic play to Broadway, while needing to replace Nicole, a key cast member. Plus there’s the not-so-small matter of Charlie and Nicole’s faltering intimacy, which may have triggered a larger issue of his affair with a middle-age backstage crew member, who we glimpse looking decidedly gloomy that Charlie’s not moving in with her. As plot devices these suffice as reason enough for Charlie and Nicole to call it quits, but that’s not Baumbach’s game. They’re a passable setup for raising the curtain onto the 40 miles of bad road the writer/director is eager to get this couple launched on.

Enter Laura Dern in Los Angeles as Nicole’s lawyer, Ray Liotta and Alan Alda as Charlie’s lawyers. Nasty, nasty, nasty. Baumbach’s screenplay has devoted upfront screen time and inventive energy defining this husband and wife as endlessly supportive, devoted partners and parents, despite all those pesky flaws that have occasioned their separation. Dern, Liotta and Alda will spend the rest of the movie arguing the case, so thoroughly researched by Baumbach, that the former partner of their client is a rotten, irresponsible, undeserving creep.

We don’t have to remember any of Charlie or Nicole’s flaws, because Laura, Ray and Alan—proven heavyweight talents, each equipped with battle-tested strategies designed to wound and maim and cripple—are going to enlarge every character defect they can uncover in Nicole and Charlie’s past, up to IMAX screen proportions.

And so Marriage Story, which starts as a dual-portrait, viewer-friendly update of Kramer vs. Kramer, morphs into a bitterly amusing, sharp-elbowed battle royale that might carry the subtitle, Charlie & Nicole vs. The Law. It’s the law books that ratchet up the tension and eventually lead the increasingly confused, frustrated, alienated and even frightened couple into squaring off against each other with unbridled fury. You have no choice but to stay leaned in through scenes that may leave you breathless and shaken. Charlie and Nicole are trapped in legal mazes neither will ever triumph in. Imagine the long-term effect on their son, Henry.

After one fest screening, Baumbach mentioned how Ingmar Bergman’s indelible drama Persona, with its joining and splitting of images of its two characters, was an important influence in his creation of Marriage Story. Make no mistake, Baumbach has fashioned, and his stellar cast has delivered, a solid centerpiece that approaches the critical level of Bergman’s masterpiece.

Born To Be; Tania Cypriano; USA, 2019; 92 min.

From the outside, Mount Sinai Hospital looks no different from nearly two dozen other major medical centers around Manhattan. But for the past two years, in its Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery on 7th Avenue in Chelsea, over 1,200 transition-related surgeries and care have been provided to s vastly diverse population of transgender and non-binary persons, as well as victims of female genital mutilation. This is a first in New York City.

CTMS’s director, Dr. Jess Ting, who agreed to open his consultation rooms and operating theaters, plus his own home, to a feature-length documentary, is instantly likable. He tells us candidly this is not how he envisioned his life. A native New Yorker and Julliard graduate who studied to become a classical musician, he still practices his standup bass whenever he has a free hour. He was first in his graduating class at the Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons. He’s a devoted cisgender dad. For years he was a successful plastic surgeon. He’d never even met a trans person. When the opportunity arose at Mt. Sinai to start a practice open to all transgender and non-binary individuals, Dr. Ting took it because “everyone else said no except me.”

Director Tania Cypriano clearly won his trust. Her documentary wins the viewer’s trust as well, and it may well win hearts with its clarity and compassion. Born To Be is respectful as it openly shares half a dozen patient histories—their frustrations and fears, hopes and desires. Nearly half of all trans patients have attempted suicide before their first appointment. Cypriano even includes one example of a patient who appears thrilled with the results of a procedure, exclaiming “for the first time in my life, I love myself!”— but after being abandoned in a bar on a date with a straight man, swallows a nearly fatal overdose of pills.

The director is discreet in almost never showing close-ups of actual surgery. Cypriano focuses on process— how Dr. Ting has built a robust practice by bringing in world class experts in trans surgery, starting with Dr. Marci Bowers (pictured) a California gynecologist and surgeon who’s performed 1,600 male-to-female and 400 female-to-male surgeries. She’s become Mount Sinai’s visiting expert and lead teacher in vagainoplasty and phalloplasty. Dr. Jens Berli from Portland, Oregon has been another visiting phalloplasty expert. Dr. Ting obviously learns fast, adding a new procedure—already known as the Ting Phalloplasty—that produces a more realistic, more sensitive phallus.

Not every consultation leads to the operation room. There are discussions of hair color, makeup, dress, breast augmentation, facial feminization and other gender markers. For every hour Dr. Ting spends in the OR, there are 10 hours of consultation and 20 hours of aftercare followup. His staff now includes ten full-time surgeons experienced in plastic and genitourinary surgery as well as obstetrics and gynecology. CTMS also has a Fellowship program that trains trans surgeons.

Getting an appointment with Dr. Ting requires patience—New York state now requires all health insurance plans to cover gender-affirming surgery.

Cypriano shows the overworked leader being gamely steered from consultation room to consultation room by an alert and sympathetic staff. His upbeat enthusiasm is unending, even when he’s wolfing down a few gummy bears as energy boosters. At home, watching his fingers move deftly up and down as he bows an instrument almost as tall as he is, we sense these are among the precious few moments this doctor reservers to renew himself.

The apt and memorable title Born To Be may have been inspired by the 1978 French disco rocker, Born To Be Alive, which is heard over the end credits.

The Marvelous Misadventures of The Stone Lady; Gabriel Abramtes; France, 2019; 20 min.

The two enchanting shorts in this festival are both from France, and each salutes a famous Paris institution. Abramtes sets his fairy tale in The Louvre, as a tour guide leads a school group through classic museum works including the headless Victory of Samothrace, usually called Winged Victory. “Anger is growing in France today,” lectures the guide, “and people want change.” The children want none of this and ask to see Jean-Jacques the famous hippo. Alas, it’s closing time, and the little stone hippo stands forlorn as the museum empties. The lights go out throughout the galleries. Winged Victory and a life-size Stone Lady, sculpted and gowned in white marble, are bathed in moonlight.

Both come to life. The Stone Lady climbs down from her pedestal. The Victory chap floats down above her. “Don’t be seen, don’t leave the museum, and don’t break anything, especially not yourself,” he cautions. They stroll past some of the world’s great paintings. The Stone Lady feels bad that her picture is rarely taken by visitors.bShe’s resigned to staying “a refreshingly banal ornamental sculpture” forever.

So the Stone Lady wraps herself in a red poncho, dons sunglasses, and takes a walk outside. Paris around the Louvre and along the Seine is quiet, except for a noisy group of students holding a rally. The speaker is predicting a revolution is coming.

Instead it’s the police, and there’s a nasty dust-up. The students disperse but the Stone Lady get beaten by a policeman, losing a leg. She borrows a bike and pedals one-legged back to The Louvre, carrying her other leg in the bike basket. Limping back to her pedestal, she slips climbing up and falls—oh dear— this time shattering into a hundred pieces.

The commotion has awakened Jean-Jacques and he commiserates with her talking head. My fault, she admits. Later, we watch the museum staff reassembling the Stone Lady, piece by piece. It’s a marvelous restoration. The next night, Jean-Jacques waddles back up. He’s going to visit a friend in New York, and invites her along. She thinks he’s pretty cute and climbs down—very carefully—to join him.

Abramtes’ script is loopy in spots, but his visual execution, using seamless motion capture suits, is kind of thrilling. Kudos to IrmaLucia VFX company in Lisbon.

Circumplector; Gaston Solnicki; France, 2019; 3 min.

The Latin title means to surround and embrace. This mediation, only three minutes in length, was filmed in and outside Notre Dame last April, several days before a devastating fire nearly destroyed the Paris landmark. It’s a vivid testament and reminder how film can preserve life’s security and serenity.

We watch one of the 16 statues of the Cathedral’s evangelists and apostles being carefully lifted down by crane, to be removed and cleaned. Ironically, it has no head, like the chatty Winged Victory in Abramtes’ Stone Lady short.

Interiors are being covered for some restoration task. A chap vocalizes a quiet treatise in Latin on the sanctity of closure. An office administrator is absorbed in her paperwork. There’s an image of an impossibly complex map or mosaic. A bowl of fruit reposes in graceful sunlight. Just another totally routine day at Notre Dame, which we view with a kind of hushed awe, because we know it’s the calm before the storm. It’s how life was lived here for 850 years, and will never quite be the same again.

Circumplector and The Marvelous Misadventures of The Stone Lady are both worthy tributes to their glorious institutions.

The Booksellers; D.W.Young; USA 2019; 99 min.

Why would you seek out a documentary on New York’s antiquarian book trade when you could be home reading? After all, the idea through much of the 20th century was to first read the book (like John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, Jack London’s Martin Eden, Sinclair Lewis’ Dodsworth or Richard Matheson’s Incredible Shrinking Man), then go see the movies by John Ford, Pietro Marcello, William Wyler, and Jack Arnold. All four of these films, still available in their expensive modern first edition hardcovers (Matheson’s sci-fi thriller was a 25-cent paperback original) were shown in this festival.

That’s not how the read-the-book-see-the-movie equation works anymore. You’re far more likely to watch these movies and then find your way back to their print sources. There are exceptions to this. All the James Bond novels by Ian Fleming and nearly anything by Philip K. Dick power the movies made from them. Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird and Truman Capote’s Breakfast At Tiffany’s forever attract casual readers (and playgoers) as well as the dedicated collector. When Larry McMurtry won the 2006 Oscar for his adaptation (with Diana Ossana) of Annie Proulx’s Brokeback Mountain, he told a global viewing audience “remember, it was a book before it was a movie.” Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn and Brandt’s I Heard You Paint Houses hope to add mileage from their filmings by Norton and Scorsese.

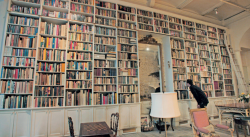

D.W. Young’s crisp, historically comprehensive and unflinching appraisal of New York City’s high end book trade celebrates the players who often “help you find what you’re not looking for.” One dealer at the annual Antiquarian Book Fair at the Park Avenue Armory muses that “my Ph.D is in 16th century Spanish lyric poetry, which explains why I left academia totally broke and entered the rare book trade.” The Armory shows draw private collectors, other rare book dealers, and big name universities and libraries. This is the highest end of the biz, where Gay Talese and Fran Lebowitz explore booths in which jeweled bindings, Gutenberg bibles, Shakespeare folios, Leonardo notebooks and original pressings of Edgar Allen Poe’s “Tamerland” are among the holy grails. “If it’s in a glass case, don’t show it to me,” grumps Lebowitz, “because I don’t have $85,000 to spend on a book.”

The city’s 2019 book scene is nearly a century removed from the original Book Row in Greenwich Village, where 48 dealers, known collectively as The 4th Avenue Booksellers (The Strand, The Corner Book Shop, Biblo & Tannen, the Pageant) once plied their trade in the early 20th century. The Strand on Broadway is an original survivor in the used and rare category, with one tiny neighbor, Alabaster Books, tucked around the corner on 4th Avenue. The Strand still has a commanding rare book room on the third floor of the building it owns. Weiser Antiquarian Books continues its 94th year, online.

Well remembered used and rare book stores including the Gotham Book Mart (“Where Wise Man Fish”), Rob Warren’s Skyline, Eeyore’s, the Military Bookman, Black Books Plus, the Compleat Traveler, The Oscar Wilde Bookshop, Colosseum, Murder Ink, The Black Orchid, Partners in Crime and Gallagher’s Paper Collectibles have all closed.

Judith Lowry, pictured with her sisters Naomi and Adina, are the third-generation midtown proprietors of The Argosy, in a five-story building they own, a far cry from the store’s 4th Avenue roots. The Argosy bills itself as New York’s oldest independent bookstore, with increasingly important ephemera sidebars like autographed playbills and sports memorabilia. Other upscale dealers like Glenn Horowitz are finding new markets for literary archives, letters, manuscripts and original drafts of screenplays. The broad field of ephemera, including original illustrations and paintings for book covers, author notes, annotations and early drafts, now comes under the heading of “historical evidence.” Says author Susan Orlean: “I had a hard time thinking of myself as a student’s homework.”

Dave Bergman, an Upper West Sider who’s the paleontology specialist in town, turns up often in Young’s doc, putting us on a more level playing field. Though his professional logo sports a fearsome dinosaur and his interests sprawl from fossil fish into the catacombs of Rome, Bergman seems more at home riding his bike to Central Park, where he plays softball with pickup teams. He may be the lone antiquarian who also sets up a sidewalk book table on weekends, offering mid-level hardcover fiction. And he’s among a shrinking number of booksellers who still hit the road to find treasures, perhaps following the back country trails of veterans like James Cummins and Otto Penzler. “The internet has killed the hunt,” reflects Bergman.

Many New York used and rare specialists like Heather O’Donnell and Rebecca Romney (of Brooklyn’s Honey & Wax), Lizzy Young, Justin Schiller, Adam Weinberger and Bibi Mohammed hope for their phone to ring from the city’s aging population—widows and retired couples (or their children) ready to de-access massive collections from collapsing shelves. As they say, there’s “eight million stories in the Naked City,” and a lot of them never moved. Collector and bibliophile Michael Zinman contributes a quick, vivid price quote on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, a novel that might be on Mom or Dad’s book shelf, covered with dust: “An unjacketed first edition is a $5,000 book, a first edition with a tattered dust jacket could be a $15,000 book, but a first with a fine dust jacket is a $150,000 book.”

First printings of most jacketed fiction by major 20th century authors are dropping in value. Firsts signed by the author are more collectible, and “association copies” inscribed by the author to a well-known person, or more particularly a famous person, can perk up the most interest. Rare book auctions also inflate perceived values. Fran Lebowitz puts her finger on a major change when she reflects “what we used to call the art world is now known as the art market.” The booksellers here affirm the same principle—yesteryear’s antiquarian book world is today’s antiquarian book market.

Still and all, books outlast us, notes Ms. Orlean. We collect them for the same reason NYFF’s curators chose that three-minute short on Notre Dame, days before its fire—to preserve our memories, our culture, our hours of time well spent. One of director Young’s most striking inter titles is a quote from a novel effectively translated to the screen in 2000, and shown several weeks ago in a retrospective presented by Film at Lincoln Center. The picture was The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton, and it attracted a nice crowd for a weekday afternoon. Wharton’s 1905 inter title holds up even better, even longer: “Don’t you ever mind,” she asked suddenly, “not being rich enough to buy all the books you want?”

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 10th annual edition of DOC NYC, November 6-15.

Regions: New York