The New York Jewish Film Festival Jan. 15-28

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw celebrates three father/daughter features that touch the heart and mind

The nice curators at The Jewish Museum and Film at Lincoln Center have made their own special mitzvah to the city’s residents in January. Out of 30 narrative dramas, documentaries and shorts that comprise the 29th NYJFF, not one, not two, but three separate feature films having their New York premieres are intelligent father/daughter dramas. Mazel tov!

For American audiences who’ve lived through one-too-many movies with dads portrayed as comical klutzes or reactionary grumps, this is welcome news. All three of these brand new releases join a tiny, splintered category in which your fondest adult/child movie memories may be your oldest ones—Father of the Bride, To Kill a Mockingbird, Paper Moon. The closer you get to today, the more troubled the dads or the daughters become—On Golden Pond, The Descendants, Trouble with the Curve, Leave No Trace, Toni Erdmann. There’s a hunger for stories of believable characters (fathers and daughters) who start out seriously flawed or emotionally damaged, but have the potential for redemption. Here are three:

For American audiences who’ve lived through one-too-many movies with dads portrayed as comical klutzes or reactionary grumps, this is welcome news. All three of these brand new releases join a tiny, splintered category in which your fondest adult/child movie memories may be your oldest ones—Father of the Bride, To Kill a Mockingbird, Paper Moon. The closer you get to today, the more troubled the dads or the daughters become—On Golden Pond, The Descendants, Trouble with the Curve, Leave No Trace, Toni Erdmann. There’s a hunger for stories of believable characters (fathers and daughters) who start out seriously flawed or emotionally damaged, but have the potential for redemption. Here are three:

Aulcie; Dani Menkin; Israel, 2019; 75 min.

Dad, the storyteller and narrator of writer/producer/director Menkin’s assured and confident Opening Night documentary, is Aulcie Perry. If you’re a deep basketball fan, you might recall Perry as a 6’10” college grad who was hired and promptly cut by The Knicks decades ago, then instantly recruited by Maccabi Tel Aviv to boost their chances of competing for the European Champion’s Cup. Maccabi wanted a treetop-tall American miracle worker; the other starting center they imported was seven feet, but this time Aulcie made the cut and stayed. To play in Israel’s national league in the 1970s, Perry needed to become an Israeli citizen, which meant becoming a Jew. And so he did, taking the name Elisha Ben Abraham. In ’77, with Perry on board, Israel beat Russia to win the Cup, and Israeli sports have never been the same.

Dad, the storyteller and narrator of writer/producer/director Menkin’s assured and confident Opening Night documentary, is Aulcie Perry. If you’re a deep basketball fan, you might recall Perry as a 6’10” college grad who was hired and promptly cut by The Knicks decades ago, then instantly recruited by Maccabi Tel Aviv to boost their chances of competing for the European Champion’s Cup. Maccabi wanted a treetop-tall American miracle worker; the other starting center they imported was seven feet, but this time Aulcie made the cut and stayed. To play in Israel’s national league in the 1970s, Perry needed to become an Israeli citizen, which meant becoming a Jew. And so he did, taking the name Elisha Ben Abraham. In ’77, with Perry on board, Israel beat Russia to win the Cup, and Israeli sports have never been the same.

Menkin told the Maccabi story two years ago in Menkin’s documentary, On the Map, which was executive produced by Nancy Spielberg. In Aulcie, Spielberg’s back in the same role, but this doc has a different through-line: it’s a letter Aulcie’s writing to the college-age daughter he abandoned at birth, along with her mother. Dad is seeking a first meeting and possible reconciliation with Cierra, who has no idea who her biological father is.

From the get-go Aulcie is a chronicle of a father starting the painful process of making amends and seeking redemption, through the possible forgiveness of his daughter. Your response as a viewer is bound to be influenced by the humility and dignity of the storyteller—his ultimate humanity—as he spins out his daunting rags-to-riches-to-drugs-to-prison life. It’s not a pretty story, but as Aulcie won’t conceal the worst of himself, he has the potential to become a kind of ‘bent hero’ when he finally demonstrates the best of himself.

“He was a random, small-college player who was lucky to get a contract anywhere in the world,” says Sports Illustrated’s Alexander Wolff, “but he turned himself and his teams into the kings of Europe.” Perry embraced Tel Aviv’s fast life in the 80s, falling in love with six-foot supermodel Tami Ben-Ami—they became Israel’s first Power Couple, though they didn’t marry.

“He was a random, small-college player who was lucky to get a contract anywhere in the world,” says Sports Illustrated’s Alexander Wolff, “but he turned himself and his teams into the kings of Europe.” Perry embraced Tel Aviv’s fast life in the 80s, falling in love with six-foot supermodel Tami Ben-Ami—they became Israel’s first Power Couple, though they didn’t marry.

When the Maccabi won its second championship in ’81, Perry began leaning on pain pills for a hurt knee. His court performance suffered; two years later fans began booing and flinging coins. Addictions to marijuana, hashish, cocaine and heroin followed. When Perry missed a game at Madrid, photographers banged on Tami’s door, but she couldn’t rouse him. As part of a court settlement on drug charges, Perry was ordered to leave the country he’d barely settled into. Languishing in Amsterdam, he was arrested for distributing hard drugs and sentenced to ten years in a North Carolina federal prison.

Out of the ashes of Auslie Perry’s near-fatal fall are born a series of events you’ll watch closely. Dani Menkin’s production shifts locales and time sequences back and forth with a seamless artistry, overlaid with frequent bursts of photo and animated montages that stir the darkening shadows. It helps to know that Menkin’s production company, Hey Jude, was named not just for the 1968 Beatles’ song, but for one indelible lyric: “Take a sad song and make it better.” That’s what this lead NYJFF documentary aims for.

Aulcie premieres Thursday January, 16 at 8:30 p.m. at the Walter Reade Theater in Lincoln Center. Aulcie Perry, Dani Menkin and Nancy Spielberg will appear.

Those Who Remained; Barnabas Toth; Hungary, 2019; 83 min.

The shadow of World War II hangs heavy over every NYJFF. Budapest, 1948, an exhausted city wearily transitioning to Communist Party domination. Dr. Aladar Korner, a gynecologist we see delivering a baby in the opening scene, has the kindest face and the saddest smile imaginable. He’s 42 and played by Karoly Hajduk, a perfect casting choice to play a physician whose wife and two sons have perished in the camps.

The shadow of World War II hangs heavy over every NYJFF. Budapest, 1948, an exhausted city wearily transitioning to Communist Party domination. Dr. Aladar Korner, a gynecologist we see delivering a baby in the opening scene, has the kindest face and the saddest smile imaginable. He’s 42 and played by Karoly Hajduk, a perfect casting choice to play a physician whose wife and two sons have perished in the camps.

A girl from the Israelite Community Orphanage orphanage, 16-year-old Klara (Abigel Szoke) is brought to Dr. Korner’s office for her first adult examination. He demurs and will recommend a local pediatrician instead. But Klara returns to his office and asks him to walk her home to an aunt (Mari Nagy, fragile and gentle) who’s taken her in, and who the girl detests. We learn Klara has lost her parents and younger sister in the camps as well, though she hasn’t accepted this; she writes to her family and thanks about them constantly. (The girl’s family and the doctor’s family are shown in photo album snaps and flashbacks, in happy times.) Klara is desperately lonely and shows it. Dr. Korner is too, but only his face hints at this. When Klora asks the doctor for a hug outside her aunt’s apartment building, he hesitates a moment, then gives her a protective hug.

You’ll watch this with wary eyes, because there’s some kind of relationship being forged here, and it’s essential one trusts the director’s instincts. Toth helps. His screenplay, co-adapted with Klara Muhi from Zsuzsa Varkonyi’s 2004 novel, builds in a vital truth we need to witness —that adults in Hungary who survived the war (including Korner’s pediatrician colleague and his wife) often became foster parents to Jewish orphans whose parents didn’t.

You’ll watch this with wary eyes, because there’s some kind of relationship being forged here, and it’s essential one trusts the director’s instincts. Toth helps. His screenplay, co-adapted with Klara Muhi from Zsuzsa Varkonyi’s 2004 novel, builds in a vital truth we need to witness —that adults in Hungary who survived the war (including Korner’s pediatrician colleague and his wife) often became foster parents to Jewish orphans whose parents didn’t.

A relationship does form. Klara’s a smart, outwardly snappy young rebel who reads Thomas Mann and beats the doctor at chess. She stays over in his clean but drab apartment and tidies up his non-descript wardrobe. He helps her with her homework. She does some cooking—in post-war Budapest, food is as scarce as electricity. When the doctor’s colleague asks her age, his reply is “she can be anywhere between 5 and 70.” Slowly “Sunny” (the nickname he gives her) begins to accept “Aldo” (the nickname she gives him) as a replacement for the dad she’ll never see again.

Life keeps interrupting this quiet two-hander: Dr. Korner becomes acquainted with an attractive, middle-age patient he’s examining unclothed, whose fiancé disappeared in the war, just as Klara discovers a slightly older and attractive boy. A school administrator spots the doctor on a park bench with Klara’s head on his lap. The pediatrician ruefully admits he’s joined the Communist Party and his first task is to identify three traitors. He’s looking directly at his good friend Dr. Korner.

What happens in the next scenes and seasons, up to the death of Russian premiere Josef Stalin in 1953, is yours to discover. But believe this: after sitting through too many bad adult/child movies, your critic wouldn’t steer you to anything but a good one. Those Who Remained is Hungary’s official Oscar entry.

Those Who Remained will premiere Thursday January, 23 at 3:30 p.m. and 9:00 p.m. at the Walter Reade Theater. Barnabas Toth will appear.

The Day After I’m Gone; Nimrod Eldar; Israel, 2018; 95 min.

Details, details, details. The viewer’s last unforgettable indie debut peppered with scores of tiny, defining observations of daily life was the 2012 drama, Neighboring Sounds. It was Kleber Mendonca Filho’s first feature, an unforgettably detailed study of a dozen neighbors in the Brazilian city of Recife. These clustered, working class residents, many of them struggling, stared out of low windows facing a luxury cityscape rising up around up around them and passing them by.

Details, details, details. The viewer’s last unforgettable indie debut peppered with scores of tiny, defining observations of daily life was the 2012 drama, Neighboring Sounds. It was Kleber Mendonca Filho’s first feature, an unforgettably detailed study of a dozen neighbors in the Brazilian city of Recife. These clustered, working class residents, many of them struggling, stared out of low windows facing a luxury cityscape rising up around up around them and passing them by.

The title of Nimrod Eldar’s debut feature, The Day After I’m Gone, alerts us to how life in Tel Aviv is being lived by Yoram (Menashe Noy), a 50-year-old veterinarian, and his teenager, Roni (Zohar Meidan). Neither have fully mourned nor adjusted to the passing of his wife and her mother. Yoram spends evenings looking out their comfortable high-rise windows at the giant, slowly turning ferris wheel in Luna Park’s dramatic night, but for him it’s stopped moving. The city has its own nocturnal sounds, but Yoram’s world is silent. Emotionally he’s frozen.

More accurately, he’s a frozen observer, whether he’s repairing an injured jaguar on his operating table, watching vehicles puttering through his safari park while being cautioned to stay away from the rhinos, or driving carefully through a noisy protest march in the streets. Like his fellow director Filho, half a world away, Eldar works hard on inventing offbeat, vaguely threatening moments and actions that once might have seemed normal but now feel tinged with tension. Alfonso Cuaron did this big time in Roma, winning baskets of awards, but Filho and Eldar are eavesdropping on the same human territories just as knowingly.

When Yoram’s daughter Roni turns up, sullen and blank after a two-day absence, there’s not much of an exchange with Dad. Maybe she’s been using— she admits being rejected by a band she wanted to join. She’s clinging to her devices and social media, none of which he uses or understands. In his clinic Yoram has authority, but as the new head of household, he’s a cipher. Then one night Roni overdoses on pills and is rushed to hospital by Tel Aviv’s ultra-efficient ambulance technicians, where she’s saved. Yoram is asked a flock of questions by EMS, administrators and social workers. Mostly he’s annoyed because he’s never had to be responsible for much of his daughter’s existence. (Plenty of viewers will identify, instantly.)

Eventually Yoram elects to break the ensuing standoff between himself and the depressed Roni by driving to visit his late wife’s family. They live in occupied Palestinian territory near the Dead Sea. Yoram spends a long time packing up his wife’s dresses, to give to her family. They give a ride to a traveling magician, who won’t explain or even perform tricks for him. There’s a tension with border guards that’s palpable. Yoram and Roni visit the grave of the deceased wife and mother, where, perhaps, there are hints of healing between them.

Eventually Yoram elects to break the ensuing standoff between himself and the depressed Roni by driving to visit his late wife’s family. They live in occupied Palestinian territory near the Dead Sea. Yoram spends a long time packing up his wife’s dresses, to give to her family. They give a ride to a traveling magician, who won’t explain or even perform tricks for him. There’s a tension with border guards that’s palpable. Yoram and Roni visit the grave of the deceased wife and mother, where, perhaps, there are hints of healing between them.

And there’s something else they pass on the way, that’s even more gigantic and vivid than that ferris wheel—a huge, deep sinkhole, the size of a football stadium, that’s opened up off the highway, near the family’s home. It’s yet another walloping image, and it may not surprise you that Roni eventually finds her way to its edges.

Actors Noy and Meidan are both extraordinarily believable as father and daughter, in part because the director is firmly anchored to the idea that Israel, for all its wars and conflicts and oddities, is getting through the day just fine, with or without either of them. Their suffering is private and personal—it’s not Israel’s doing. That’s the whole being and purpose of that ferris wheel Dad’s keeping his eye on, both at the start and at the conclusion of this thoughtful film. The wheel keeps turning. Father and daughter now have to start turning, too, if they don’t want to disappear into that sinkhole. Every city dweller who watches The Day After I’m Gone will intuit this. In his way, Eldar is doing the same thing Dani Menkin’s Hey Jude company is doing with Aulcie Perry and his daughter Cierra: he’s taking a sad song and trying to make it better.

The Day After I’m Gone premieres Monday January, 20 at 9:15 p.m. and Sunday, January, 26 at 1:00 p.m. at the Walter Reade Theater.

The 29th NYJFF includes eight arresting shorts. Two of the most original selections are fascinating looks at how Jewish daughters grow up:

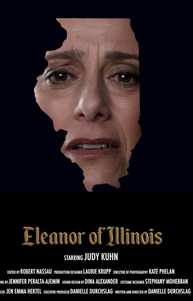

Eleanor of Illinois; Danielle Durchslag; USA, 2019; 6 min.

Consider the passages below, acted by Katharine Hepburn in her 1968 Oscar-winning performance as Eleanor of Aquitaine in Anthony Harvey’s The Lion in Winter. She’s speaking to Henry II:

Consider the passages below, acted by Katharine Hepburn in her 1968 Oscar-winning performance as Eleanor of Aquitaine in Anthony Harvey’s The Lion in Winter. She’s speaking to Henry II:

“It’s 1183 and we’re barbarians! For these ten years you’ve lived with everything I’ve lost, and loved another woman through it all. Suppose your first son dies, ours did. Suppose you’re daughtered next, we were. How old is daddy then? What kind of spindly, ticket-ridden, milky, wizened, dim-eyed, gammy-handed, lumpy line of things will you beget? …I could peel you like a pear and God himself would call it justice! …I’m cold, I can’t feel anything, not anything at all. I want to die.”

The filmmaker, Danielle Durchslag, grew up entranced with this movie version of James Goldman’s Broadway play. Like Queen Eleanor’s children in their English royal family, she saw what she describes as “my own family dynasty, an American Jewish one whose money and influence were part of my lived experience of familial control, obligation and conflict.”

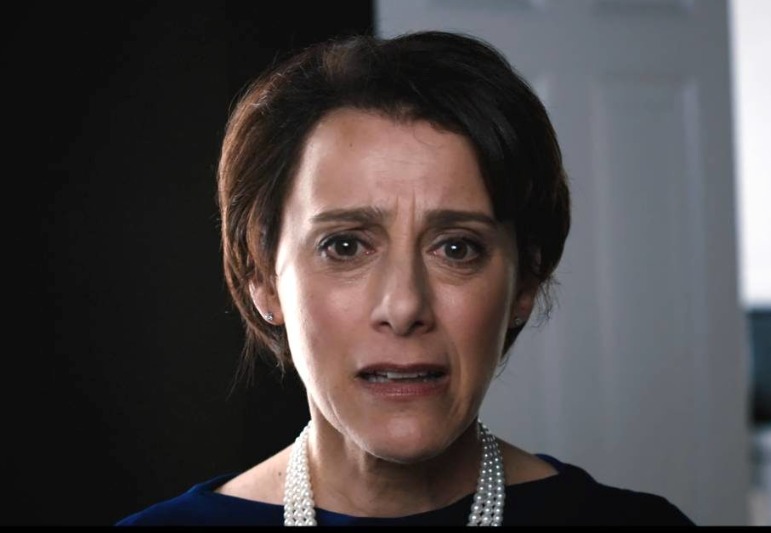

Durchslag chose one of Broadway’s premiere actresses and four-time Tony nominee, Judy Kuhn, as a doppelganger for Hepburn. She then spent a year adapting and crafting six minutes of Hepburn’s dialogue into a portrait of a bitter, wealthy midwestern Jewish woman. What we hear is a dual, blended monologue of Hepburn’s distinctly recognizable voice mixed with Kuhn’s simultaneous on-camera interpretation of the same lines. She’s lamenting her anguish over her dysfunctional family and its extreme wealth to her daughter, who is the camera and thus the viewer. This is surely the most innovative, uneasy and oddly dramatic short film over the past decade of NYJFF. But only—and one can’t emphasize this strongly enough—only if you know what you’re about to experience before viewing.

Durchslag chose one of Broadway’s premiere actresses and four-time Tony nominee, Judy Kuhn, as a doppelganger for Hepburn. She then spent a year adapting and crafting six minutes of Hepburn’s dialogue into a portrait of a bitter, wealthy midwestern Jewish woman. What we hear is a dual, blended monologue of Hepburn’s distinctly recognizable voice mixed with Kuhn’s simultaneous on-camera interpretation of the same lines. She’s lamenting her anguish over her dysfunctional family and its extreme wealth to her daughter, who is the camera and thus the viewer. This is surely the most innovative, uneasy and oddly dramatic short film over the past decade of NYJFF. But only—and one can’t emphasize this strongly enough—only if you know what you’re about to experience before viewing.

Credits, please. Durchslag shot in a luxury suite of Manhattan’s Pierre Hotel. Her Katharine Hepburn sound editors were Gisburg Smialek and Brian Jackson. Dina Alexander was her dialogue and music editor, additional Hepburn sound editor, sound design and sound mix editor. We’re talking Academy-level artistry here in six minutes.

Eleanor of Illinois is part of the Shorts by Women program showing Sunday January, 26 at 8:00 p.m. in the Walter Reade Theater. Danielle Durchslag will appear.

Marriage Material; Oran Zegman; USA, 2019; 25 min.

If you’re a film student planning to write and direct your first knockout short, here’s the review you’ll print out and tape to your computer screen frame. It will become your forever inspiration. Because what’s happened to Oran Zegman, the determined Tel Aviv native pictured below directing her dance chorus, might one day happen to you.

If you’re a film student planning to write and direct your first knockout short, here’s the review you’ll print out and tape to your computer screen frame. It will become your forever inspiration. Because what’s happened to Oran Zegman, the determined Tel Aviv native pictured below directing her dance chorus, might one day happen to you.

In what seems no more than a New York minute, Marriage Material has become (CUE THE MUSIC) the first musical made at The American Film Institute in its 51 year history…(BUILD THE MUSIC) a Finalist for the 2019 Student Academy Award…(PEAK MUSIC) and has been acquired by Fox Searchlight Shorts where it will be available on Fox Searchlight’s YouTube channel and ‘Searchlight Shorts’ Facebook page. What a wowzer calling card for Zegman.

You may want to approach her master’s thesis film, budgeted at $83,000, as the dark LA underbelly of La La Land. Leah Schwartzman (Gwen Hollander) is ready to sing her heart out for a Jewish Mr. Right for the rest of her life, but she keeps finding Mr. Wrongs who aren’t even Jewish. So her parents drive her out to Yenta Feldman’s Late Blooming Bride Retreat, a woodsy, gated mansion in which unmarried Jewish girls are refurbished and reassembled into potential trophy wives. Sound like The Stepford Wives or, worse, The Lobster? (Beware, these are Zegman’s two most important filmic influences.)

Leah is branded an Alpha and is quickly immersed in Feldman’s dumbing down process of learning how to please a man by remaining forever subordinate to him. All the songs have sharp teeth. They’re smartly written and elaborately choreographed, and Ms. Hollander—an unfailingly positive, tirelessly high-energy, let’s-put-on-a-show heroine—sings away as she allows herself to be regroomed, redressed and reprogrammed into everything she’s not.

Leah is branded an Alpha and is quickly immersed in Feldman’s dumbing down process of learning how to please a man by remaining forever subordinate to him. All the songs have sharp teeth. They’re smartly written and elaborately choreographed, and Ms. Hollander—an unfailingly positive, tirelessly high-energy, let’s-put-on-a-show heroine—sings away as she allows herself to be regroomed, redressed and reprogrammed into everything she’s not.

By graduation day Ms. Feldman has magically produced a perfect young man for Leah—he’s tall, Jewish, eternally handsome. Both large families have assembled to view the wedding of this perfect couple. It’s just that Leah’s last, long look up at the hunk she’s been processed into marrying is—well, it’s a carbon copy of the look Katherine Ross gave Dustin Hoffman in 1968 at the end of The Graduate when he steals her from a church and they hightail it away on a city bus. The look on Katherine’s face mirrors the look (and maybe the thought) of Leah here, and it’s What have I done? What HAVE I done?

Marriage Material is part of the Shorts by Women program showing Sunday January 26, at 8:00 p.m. in the Walter Reade Theater.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in Rendez-vous with French Cinema, March 5-15.

Regions: New York