New York Film Festival – Critic’s Choices

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw salutes top features and shorts in Lincoln Center’s 58th annual (and first virtual) festival

How about a nice round of applause for filmmaker/artist and ‘Pope of Trash’ John Waters, pictured here with the poster (silkscreen printed on Cougar 130lb natural paper) he and Globe Poster designed for the 58th New York Film Festival. “I always knew I’d get my ass in there somehow…in 2020 we have to reinvent movie-going itself,” says Waters. Right you are, John.

The poster’s correct—there was no “waiting in line with intellectuals,” since nearly all the movies were viewed virtually. There were some outdoor showings at Bronx and Queens drive-ins, though one showing at the Brooklyn Drive-In in the borough’s army terminal was scrapped due to high winds. If you “came dressed as your favorite director,” perhaps Waters himself, you could have watched a stomach-turning double-bill he curated of Pasolini’s Salo and Noe’s Climax. In keeping with NYFF tradition, there were “no awards,” since filmmakers worldwide have forever agreed that just having their movie on this fest’s list is ample recognition.

But seriously now, readers, we need to put our hands together and start clapping for (in order of appearance) the filmmakers and distributors who agreed not to withhold their pictures for some future unveiling; NYFF’s new curatorial staff, headed by Eugene Hernandez and Dennis Lim, who creatively and vigorously filled the Main Slate, Currents, Spotlights, and Revivals categories; and all the moviegoers who surrendered to the idea of watching terrific movies on a home screen a teeny tiny fraction of the size of the majestic image usually up in Alice Tully Hall and the Walter Reade Theater. As Hollywood’s press books used to proudly proclaim in a a bygone era in which their greatest competition was radio, Motion pictures are your best entertainment.

Time; Garrett Bradley; USA; 2020; 81 minutes

There’s a moment in Sybil Fox Richardson’s life, shared in this documentary, that’s impossible to forget. Fox, as she’s known, is a Black mother of six children, married to a man sentenced to 60 years in prison for a holdup. As we gradually learn, she’s a persevering, entrepreneurial woman of stature and intelligence. When she’s not running her Louisiana auto dealership and working tirelessly to get her husband’s sentence reduced (plus moving to New Orleans to pursue a doctorate in the Administration of Justice at Texas Southern), she’s continuing to document the years spent without him.

Fox turned over to director Bradley almost two decades of sweet, grainy home videos of she and her children growing up, with and without the high school sweetheart she married and lost to prison. This becomes a black-and-white archive which Bradley and her adroit editor Gabriel Rhodes weave through Time, which is also shot in black-and-white. In this particular scene, we watch awestruck as Fox hangs a life-size cardboard blowup of her husband Rob on their living room wall. There he is, big as life, yet not there at all, and there he’ll stay until the day he walks out of Louisiana State Penitentiary. It may be difficult to watch this intimate scene with dry eyes.

Garrett Bradley’s Time is strikingly different from two other films in the past 18 months, both chosen from world class film festivals, that earned lead critic’s choice reviews in The Independent. Dani Menkin’s Aulcie, saluted in The New York Jewish Film Festival back in January, showed the life of Aulcie Perry, the 6’10” former basketball star of Maccabi Tel Aviv in Israel, who served ten years in a North Carolina federal prison for one drug offense in Amsterdam. Producer Nancy Spielberg kept the focus on Perry’s before-and-after life, as he found his own redemption in the embrace of a college-age daughter he barely knew. And in Chinonye Chukwu’s Clemency (2019, New Directors/New Films), Alfre Woodard acted a prison warden emotionally traumatized by needing to carry out the execution of a convicted killer (Aldis Hodge) who’s pleaded innocent and exhausted 15 years of appeals.

In Bradley’s documentary, Ms. Richardson demonstrates she’s neither a martyr nor a victim. She describes herself as an abolitionist, striving to right a different kind of wrong—the time people are sentenced for their offenses. (Facing the economic collapse of a community clothing store they started together, Fox and Rob committed a holdup with Fox at the wheel of their car. As first offenders, Fox took a plea deal and served three and a half years. Rob refused a plea deal for 12 years and was sentenced to 60 years.)

But Time shows how the family bond between wife, husband and children can survive injustice—can hold together through anything. This is turning the page into a different cinematic territory. And Garrett Bradley, working closely with editor Rhodes, have crafted 81 minutes from 20 years of this family’s life into a journey of unforgettable compassion and affirmation. Their work is guided along by the restless and urgent musical compositions and improvisations of Emahoy Tsegue Maryam Guebrou, an Ethiopian nun. Some are Joplinesque and melancholy, others scatter notes like breaking glass, still others are rooted deep in church organ meditation.

Fox is an enormously resourceful head of household. We watch her rehearsing and shooting a take for a television commercial for her family’s former car ownership, 7 Motors in Houston and Orange, Texas. She’s the pitch woman, crisp, confident, buttoned up. She’s smoothly persuasive on her feet and knows how to evaluate her own performance, bettering it in a second take. This is her public face. Later we’ll see her seeking forgiveness from her church’s congregation, for having lost her way. There’s no performance here, only a plaintive voice in a trusted community, asking for help. Fox’s mother, known as Ms. Peggy, appears from time to time offering strength and hope.

Another piece of filmic artistry, part of which you can view in the picture’s online trailer: Fox is on a collect call, on hold, waiting to speak with an administrative official, who’s on another call, but who may have possible news concerning Rob’s pardon. In the trailer, we don’t watch Fox patiently holding and holding, for what seems an eternity, staring into space. But in the film, we do. You’d think it would stop the movie, and it does, deliberately. But what it also does is infuse the movie with what it means to wait. And wait. And when she’s finally connected, Fox learns the person she’s waited to speak with has nothing to report. We sigh and think, all that time for nothing. Bradley and Rhodes devote every minute of screen time to showing how a family holds together, making it through years of days and nights when justice can feel on permanent hold.

Even with its modest running time, Time drills deep into the world of separation. Fox speaks longingly of how she and Rich were permitted only two brief visits together each month. “This situation is just a long time, a really long time,” sighs her son Justus. There’s a moment when we watch one small cloud ever-so-slowly drifting by itself across a wide clear sky. After Fox is successful in achieving Rich’s pardon and he arrives back home, his life-size cardboard cutout on the living room wall comes down. Rob summarizes his journey: “I said I would speak truth to falsehood, and I would finish strong.” And so this man, this couple, this family has.

City Hall; Frederick Wiseman; USA; 2020; 272 minutes

Good government works. This is Wiseman’s 45th filmic examination of many of the nation’s most famous institutions. At 90, born in Boston, America’s most enduring documentarian has taken his time getting to his home town’s city hall. One wonders if he might break with any of his lifelong journalistic practices: Eschewing conventional Q&A’s, narrative voice-overs, a music score that might affect your emotions, subtitles that would inform you who you’re looking at and what they do. Nope. Like all his bare bones docs, the usual tools of most documentarians are shelved. Wiseman’s genius as a sculptor of images is, once again, all that’s needed.

The director has said he approaches each cinematic exploration with an open mind. City Hall invites us to eavesdrop on Boston’s governmental infrastructure, last winter and in the fall of 2018—unmasked days in the Old Normal. Nearly everyone in the administration, including a healthy number of meeting leaders of color, is conservatively suited-up, and they’re on point through discussions of the budget, economic development, hunger, housing, diversity, social justice, substance abuse, whatever subject is on the agenda. A lot of points are made from careful notes, and make no mistake, government runs on PowerPoint.

As in polite meetings everywhere, there’s a lot of heads nodding in agreement with the meeting leader. What’s surprising here is the sheer volume of meetings chosen by Wiseman in which the meeting leader is Marty Walsh, Boston’s 54th mayor, another native son who was raised on the tough streets of Dorchester 53 years ago and elected to a second term in early 2018.

Walsh has the common touch infused into his leadership, an invaluable asset, whether he’s assessing ways to better spend his $3 billion-and- change annual budget, serving Thanksgiving dinner at a Goodwill pantry, or rattling though his 23 years of ongoing recovery from alcoholism to an audience of aged veterans. He’s an Irish Catholic son of immigrants, a natural champion of working women and men wherever they live in his sprawling city, and he comes across as the the nicest guy in the room who often seems the smartest guy in the room. Wiseman can’t get enough of Walsh, and so we watch the mayor steering a blitz of sessions—Latinx participation, the NAACP, nurses’ recognition, food banks, residential housing, the NRA. It’s Mayor Marty’s world, and in this chronicle it feels like he’s almost everywhere you want him to be.

Wiseman’s ever the fight trainer preparing you to go 15 cinematic rounds with this doc—here he provides mini-intermissions using picture postcard glimpses of Boston’s wildly eclectic architecture, plus brief vignettes that amply cover your trips to the concession stand, refrigerator or bathroom. Watching a long sofa being tossed into a compactor and slowly crunched up or fallen tree branches moving foot after foot into a shredder, are as relaxing as staring at TV test patterns used to be in the 1950s. So are scenes in city hall’s traffic hearing room, where, for example, a new father tries to explain away a ticket for parking next to a hydrant, because he was delivering his wife, in labor, to hospital. (He succeeds!) Wiseman must know his four-and-a-half-hour civics lesson needs some pleasant breaks, and they’re freely given.

The tonality throughout City Hall is upbeat and positive. Whatever issue Boston faces feels solvable by dedicated thinking and responsible action. One off-premises session follows a building inspector checking work-in-progress on a waterfront apartment complex, where all appears in compliance. Another shows a health worker dutifully taking notes and gently admonishing a resident with rodent problems for having food unsealed in a kitchen.

There’s not much consumer pushback on Walsh’s watch. Wiseman offers one example of a Mexican contractor plaintively complaining in a hearing that the city favors big bucks contractors in handing out contracts. And City Hall waits four hours to start its one telling session with an angry public. It’s a stunning confrontation between the entrepreneurs of a cannabis shop who’d like to open a retail operation in the rough hewn Bowdoin-Geneva section of Dorchester, and an audience of multi-racial, multi-ethnic residents of this underserved Boston community. It’s the one scheduled public hearing at the municipal level on what effect a cannabis operation may have on a community’s mental health, crime, dumpster-diving, traffic and parking. The back-and-forth is electric, and Wiseman lets both sides have their impassioned says at length.

As a cultural preservationist, Wiseman is still piling up milestones, much as Studs Terkel once did with oral histories in print and on radio, and Joseph Mitchell did in the pages of the New Yorker. Wiseman shows the world as it’s lived in Jackson Heights (New York), Monrovia (Indiana), Berkeley (California), Belfast (Maine), in boxing gyms, ballets, zoos, high schools, race tracks, libraries and so much more. Onward.

Nomadland; Chloe Zhao; USA; 2020; 108 minutes

When non-professionals take scripted acting roles, playing versions of their real-life selves, we’re into new screen territory. It goes much deeper than a lot of movies billed as “inspired by true events,” where we’re watching actors acting. It’s what might be termed a hybrid cine-memoir. And it’s a true rarity because it shows non-actors acting away all too believably.

Zhao advanced the form in 2018 with The Rider, shot in South Dakota’s Sioux community, in which a brain-injured rodeo cowboy and horse trainer (Brady Jandreau) essentially played himself. This followed up Zhao’s earlier tale of a Lakota Sioux girl, shot in South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, Songs My Brothers Taught Me. (nominee for both a 2016 Camera D’Or award at Cannes and Best First Feature at the Independent Spirit Awards). Zhao lived on that Native American reservation for several years, experiencing and scripting what she affectionately calls “Indian Cowboy” culture.

With Nomadland, Zhao expands the hybrid memoir into a global of-the-moment concept that’s building Oscar buzz by the day. The director has seized one of a zillion business shutdowns—the closing of U.S. Gypsum in Empire, Nevada in 2011, which eliminated 95 jobs, most of Empire’s population. (It’s based on Jessica Bruder’s Nomadland: Surviving America in the 21st Century.) In Zhao’s adaptation, Fern, an unemployed widow (Frances McDormand, never more ready for this role at 63), watched Empire crumble after she and her husband lost their company jobs. After his passing, Fern has stayed around until Empire loses its post office and zip code. She gathers a few items out of storage and hits the road in her box van.

Where’s she going? She has no idea. The view through her windshield is as bleak as the view from Bruce Springsteen’s 1982 album cover, Nebraska. It’s an empty highway to nowhere. Until Fran links up with Bob Wells’ Rubber Tramp Rendezvous, a tribal caravan of van dwellers who’ve built out their RVs and cargo trailers into permanent homes. By then Nomadland has fused into its hybrid form, and you’re leaning way in. It’s a perfect NYFF Centerpiece choice.

Fern survives like most part-timers, taking work wherever she can find it, to pay for gas and food. Her knees are starting to go from arthritis, she’s a smoker who won’t turn down a glass of whiskey, she plays the flute before she turns off her plastic Santa lamp to sleep. A loner, but “houseless, not homeless.” It s something of a shock watching her accepting day work packing boxes at a gigantic Amazon warehouse, in which Zhao places an amiable Fern among cheery, enthused workers. Talk about the circle of life.

We intuit right away Fern’s a survivor who’ll get along with everyone, starting with Linda May and Swankie, whose screen names are their real life names—brilliantly cast. They teach her life skills like changing a tire, choosing the right size waste bucket, and learning the collectible value of different rocks. Bob defines his fellow travelers as “workhorses who’ve been worked to death” by corporate America, then discarded. These two women plus McDormand’s Fern make up the heart and soul of Nomadland.

One fellow traveler who slides onboard early, then grows into a presence, is Dave, a divorced dad who’s thinking of visiting his estranged son and family in California. Zhao shrewdly casts David Strathairn, a chameleon wizard like Willem Dafoe or Michael Shannon who flawlessly disappears into whoever he’s playing (one still shivers at the memory of his Pierce Padgett, the escort czar in LA Confidential, over 20 years ago). Dave is drawn to Fern, who’s already surrendered a piece of her independence when she has to borrow $2,300 from her sister to pay an engine repair. We sense she’s weighing the price of freedom when she makes her way to Dave’s reconciled family in California and sees him at peace. Will she stay?

McDormand has honed the actor’s gift of doing more by doing less, into a fine art, echoing her real-life ensemble cast. McDormand, Linda May and Swankie give measured performances, equally quiet and considered. The most haunting aspect of Nomadland, its starkest truth, is when a community anywhere loses enough businesses, it withers and dies. Everyone left moves on. Bob Wells gathers in these aged orphans, affirming that no one in the RV community ever needs to say goodbye. “See you down the road” is the common farewell to old friends, maybe a kinder, gentler way of saying “see you on the other side.”

The Human Voice; Pedro Almodovar; Spain; 2020; 30 minutes

Why are so many screen stars appearing in short films? It can’t be for the money, as most shorts (up until Fox Searchlight’s YouTube channel launched a program called Searchlights Shorts last year), don’t make any. They’re calling cards for the filmmaker. And only a fraction of the thousands submitted to major film festivals ever get shown, and few of those get reviewed. Maybe the actors are irresistibly drawn to the roles, like Salma Hayak playing a Ground Zero bartender in Jim Sheridan’s indelible 11th Hour. Or Robert De Niro’s turn-of-the-century immigrant who’s turned away at Ellis Island in JR’s superb Ellis. Or S. Epatha Merkerson’s high school administrator facing down a student with a shotgun in Christine Turner’s memorable You Can Go. Or Charlotte Rampling, playing herself and discovering, watching one of her 80s movies on late night TV, that she’s been digitally removed and replaced by a “new, younger Charlotte Rampling,” in Didier Berceto’s The End. Brave performances all, and all celebrated in The Independent.

Which brings us to Almodovar’s The Human Voice, “freely adapted” from Jean Cocteau’s 1928 play of a woman on the phone with her lover who’s just dumped her after four years together. It’s an auditioning staple in acting classes worldwide—a delicious, universal monologue that’s forever attracting women of indeterminate ages: Anna Magnani in Rossellini’s L’Amour in ’48, through Simone Signoret, Ingrid Bergman and Liv Ullman, to (most recently) Sophia Loren and Rosamund Pike. It inspired Almodovar’s own Woman on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown. NYFF has given it a special spot in its Spotlights section, probably because it lets the director (the one helmer on Waters’ sassy poster with a movie in this edition) ignite the barely contained fury and sanity of Tilda Swinton. Almodovar doesn’t just light her fire and her BlueTooth ear buds in his first English-language film, he directs her to push all her “madness and melancholy” buttons clear over the edge.

In the first minutes we watch Tilda in a hardware store, examining and purchasing a hatchet. It seems she’s locked her kitchen drawers with all the cutlery, so she won’t be tempted to carve her lover up. (Oh mercy—right away viewers may be reminded of Picture Paris, a wickedly endearing 2012 short in which Julia Louis-Dreyfus stabs her cheating husband to death in their kitchen, then chops him into a hundred little pieces, bakes him into a meat loaf and hand-delivers him to his lover—their neighbor— just down the block.) But Tilda just flails away with her hatchet on her man’s fanciest outfit, then lays down next to it and places a protective hand over it. Honestly now, a suit of clothes has rarely been so lovingly destroyed.

Swinton turns 60 next month, an ideal time to deliver a master class in jealousy, loss, regret, hysteria, cunning and revenge. Almodovar has built her a lushly enthralling home and darkened terrace that’s at once coldly cosmopolitan, yet clearly a ceiling-less stage set that bleeds out onto wild walls. (All credit to Antxon Gomez, his usual production designer.) Swinton wanders back and forth, in and out of the colorless soundstage and its gorgeous set, and we never think to question a second of it. When Tilda gravely intones “my metabolism burns everything,” it’s a grim hint of what she may be planning.

Shorts – Four Kinds of Magical Realism

This year’s festival offered 45 shorts from 28 countries, bundled in eight programs titled “Currents.” Under different titles, this has been the festival’s experimental section, originally called “Views from the Avant-Garde” then the more neutral “Projections.” Many shorts have been silent 16mm explorations and meditations on form and color, curated for a patient, knowledgeable (and probably shrinking) audience, some old enough to have grown up in Manhattan’s Cinema 16 and championed shorts once heralded as “those underground films.”

Much of this history has taken a slow fade to black, along with Film At Lincoln Center’s former class-conscious name, “The Film Society of Lincoln Center.” “Currents” was this year’s more enticing title, with a goal of offering a “a bigger-tent approach, encompassing different forms of experimentation by filmmakers and artists working at the vanguard of the medium.”

One form of original experimentation that’s stubbornly survived by migrating into story forms in NYFF is Magical Realism. Simply put, magical realism is the blending of the ordinary with the out-of-the-ordinary. Fantasy on top of reality. Or reality on top of fantasy. If you’ve looked at paintings by Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keeffe, or read novels by Toni Morrison and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, or watched most any film of any length by Guy Maddin, you’ve encountered heady mixes of fantasy and reality. These are giants. But painters and authors worldwide, and a surprising number of young filmmakers making shorts, are just as interested in unearthing truths in different ways, through different lenses. Here are four memorable examples from “Currents”:

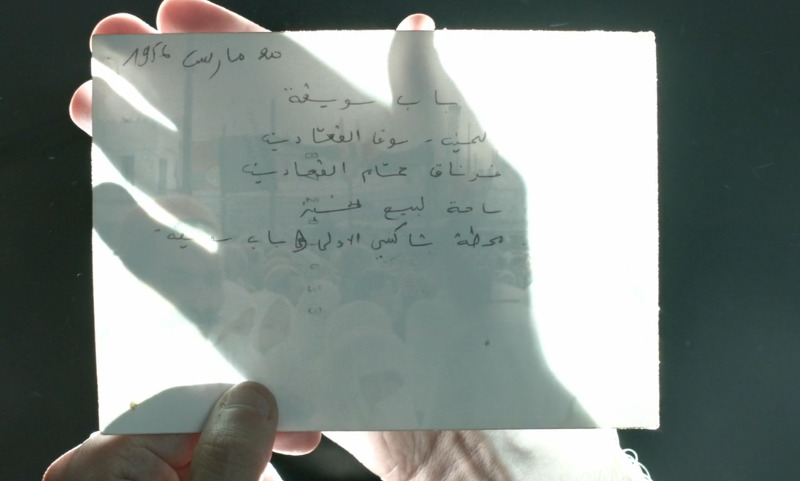

Apparition; Ismail Bahri; Tunisia/France ; 2019; 3 minutes

“To touch is to see,” director Bahri tells us. What we see in this introductory lesson to magical realism are hands holding and gently rubbing a small, blank sheet of paper. An image slowly appears, just as it did back in the mid 1970s when much of America snapped pictures with a Polaroid camera. You’d take a picture, a white blank piece of paper would pop out of the back of the camera, and you’d watch the image slowly develop before your eyes.

What emerges in this silent three minute demonstration from a blank paper is a picture taken in 1956, on the day celebrating Tunisia’s independence. We see a large crowd with covered faces in a crowded square, though there’s one uncovered face, a male, his face turned toward the camera, in lower right. He’s looking at us. The hands are rubbing the paper image as it gradually appears.

The hands flip the paper over. Again a blank. Again the hands begin to rub the paper, and again the same image appears, lighter this time—except a handwritten message now appears, superimposed over the crowd. Who wrote this? Is it the man who’s pictured, saying something to us? Is he writing us? If you can read the language shown, maybe you can solve the mystery. Perhaps you’ll discover how Bahri performed the trick. But the first principle of magic is that magicians never give away their secrets.

Aplyemiyeki?; Ana Vaz; Brazil/Portugal/France/Netherlands; 2019; 27 minutes

The serious documentary filmmaker is always attuned to incidents of importance in one’s country and culture. Ana Vaz, a Brazilian artist/filmmaker and winner of Film At Lincoln Center’s Kazuko Trust Award, cannot forget her country’s military dictatorship that nearly wiped out the Waimiri-Atroari, an indigenous people who lived along the Brazilian Amazon from the mid-1960s through to the 1980s. The colonizing regime used the building of a highway between Brasília and Amazonas as the excuse for destroying anyone on or near it. “Aplyemiyeki?” means “Why?” and now you know why this native population all but disappeared. The filmic magic that will preserve their story is in this short.

Vaz starts with neutral black and white footage of the neat, sparsely traveled highway BR-174 cleaving its way through jungle, and the mighty Amazon tributaries churning along near it. The filmmaker’s treasure is found in an archive of 3,000 drawings made by very young students of the Yawara School in 1985-86. (They were curated by the indigenous rights scholar Egydio Schwade.) The students were among the survivors. Their drawings are the history of genocide by bows and arrows, guns, grenades, dynamite and napalm bombings. Over 2,000 people of the forest perished.

What the director does is bi-pack and tri-pack multiple images—16mm color of the heartfelt sketches made then, clean black and white footage of the highway and river today—against a multi-track sound collage of wind, water, highway traffic and ominous instrumentation. The work is disciplined and organic, counterpointing the river’s enduring majesty with the highway’s disruptive presence, both working against dozens of plaintive images of suffering. Vaz has created a magical realism of astonishing poignancy.

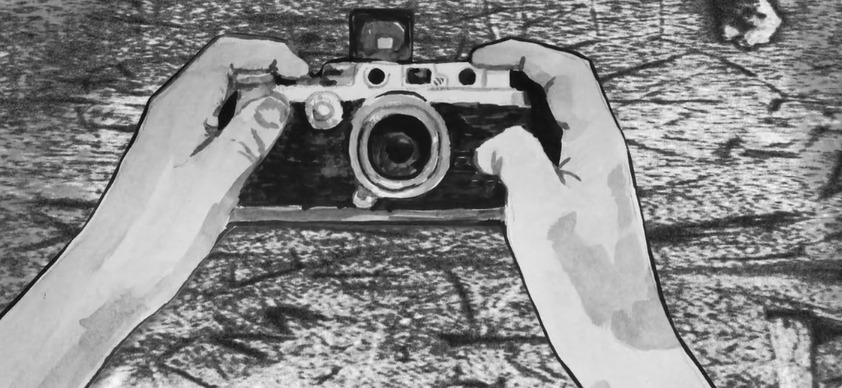

Shots In The Dark With David Godlis; Lewie & Noah Kloster; USA; 2020; 7 minutes

New York Film Festival buffs have grown up in the dark along with David Godlis. He’s been the house photographer at Alice Tully Hall and the Walter Reade Theater in Lincoln Center since 1976. Call him the archetypal fly-on-the-wall presence one barely notices—quiet, friendly, clad head-to-toe in worn downtown black, Godlis vanishes inside a darkened theater. Few remember he was also one of the Bowery’s premier street photographers and practically a fixture at CBGB’s in the late 70s, covering the punk rock scene while he studied legends like Weegee and Robert Frank. This year, following a book launch in 2016 for History Is Made At Night, Godlis finally gets his seven minutes of on-screen fame. And the directing Klosters have served up nearly all the photographer’s conceptual secrets.

At midnight the Bowery back then was “wide open nothing,” but outside and inside CBGBs every night were half a dozen blaring bands, the best tuned sound system in the Northeast Corridor, and a basement rest room no one ever rested in. Godlis, a Boston native, knew he was home at last, and wondered how he’d take street pictures indoors without a flash. So he took the exposure down to a quarter of a second, and compensated by overdeveloping—mixing the developer/water solution at one-to-three instead of one-to-five. Then he chose paper with a lot of contrast. Bingo—Patti Smith standing by the entrance looks somehow subtly and mysteriously enhanced.

CBGBs was Manhattan’s longest-running rock club, shuttering in 2006. The Klosters animate Godlis’ photos with delicious abandon, slinging and wedging them into cut-and-paste collages that make music fans feel like cardboard props in some weird urban landscape. All told, Godlis’ photos are killer Magical Realism—they make a rock short as worthy of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as Tony Jannelli and Robert Pietri’s The Velvet Underground Played At My High School, from way back in 2017.

Point and Line to Plane; Sofia Bohdanowicz; Canada; 2020; 18 minutes

Sometimes a filmmaker pushes and strains to make magical realism happen, and it doesn’t. Point and Line to Plane takes its title from the painter Wassily Kandinsky’s 1925 book, a study of how simple elements in painting (say a line with a bend), can trigger images of a person—say the arm and shoulder of a past friend, maybe even a lover.

A young woman in her 20s (Deragh Campbell, neutral and severe, perfectly cast) is mourning the passing of her friend Jack, who was 37 and died when she was in Vienna. She’s recalling places they once went, things they shared. She’s conjuring up “the freckle in the middle of his nose, his soft hands that would reach for mine in the middle of a concert, the warm laugh that came from his gut.” They both loved Kandinsky, and she’s showing us magnets from the Guggenheim of Kandinsky paintings. Various visual details match the memories she’s describing in quick, uncanny ways. We think, oh boy, maybe Jack himself will materialize in a Kandinsky, like the dead souls who appear in Toni Morrison’s Beloved. But Jack won’t turn up. The trace elements in the refrigerator magnets are all Kandinsky will yield to her.

So the young woman pushes on. She looks for J A C K in crossword puzzles. She improvises a solo dance listening to Mozart, their favorite composer. On her 39th day of mourning, a framed picture of Hilma af Klint, a predecessor of Kandinsky, falls off her wall. She takes this as a signal, perhaps a clue to recapturing Jack, as there’s a Hilma af Klint exhibit at the Guggenheim. She goes. She tries to imagine what it would have been like if she and Jack had seen the show together. Nothing appears. Nothing.

She loads her Bolex camera and flies to St. Petersburg to do research at the music conservatory. She shoots five rolls of scenics from her apartment window, still thinking of Jack, and notices the back of her Bolex wasn’t securely locked. This means the footage may pulsate and breathe. Ah! Maybe that will yield a magical image of her deceased friend. But it does not. Defeated, she wanders into the Hermitage and stares at another Kandinsky painting. It’s dense with non-specific objects, shapes, colors, vague forms. “If you can hear me, answer with the sound of color,” she silently begs Jack. “I want to know what form you’ve chosen to be.” Then she opens her eyes: “I opened my eyes and I saw.”

But we don’t see what she saw. Director Bohdanowicz, who also shot and edited this most complex of all the festival’s shorts, chooses to withhold any final information. She won’t venture beyond the tantalizing matching images that began her subject’s search. It’s a daring artistic decision, what’s more commonly derided as an artistic conceit, but in its own surprisingly magical way, it works.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in DOC NYC, America’s largest documentary festival, November 11-19.

Regions: New York