Tribeca 2010 Critic’s Choice: “Visionaries”

Visionaries

(Chuck Workman. 2010. USA. 90 min.)

If you were tasked with pulling together a comprehensive history of experimental cinema from the 1920s through today—running exactly 90 minutes—who would you trust to research and assemble such a formidable project? Chances are Chuck Workman would top your list; his reputation as the premiere montage specialist has soared over 20 years of Oscar telecasts, starting with an eight-minute short (Precious Images) in 1986 that won Workman his own Academy Award, and expanding through well-regarded docs on the beat generation The Source and Superstar: The Life and Times of Andy Warhol. We’ve come to cherish Workman as the ultimate heads-and-tails guy—the editor who can artfully compress worlds of imagery into quick, meaningful glimpses that define entire careers in mere seconds.

What Workman accomplishes in Visionaries is not just an absorbing and abiding portrait of the essential founder of experimental cinema and his New York “cathedral,” the Anthology Film Archives, but a sweeping, delicious journey, easy to follow and packed with insights into the work of scores of innovators. Visionaries is Workman’s triumph, a sum-up that educates, informs, delights, exasperates, surprises, annoys, vexes, and challenges us as celebrants of independent film. It’s a textbook on alternative celluloid, filled with rebels who refuse to behave themselves and make no apologies.

Mekas, at 78, sporting a jaunty wardrobe of fedoras and work shirts that look like they could be Lithuanian war surplus, is most memorably shown padding about and through some 65,000 reels-in-cans. It’s floors and floors of amiable clutter, and it’s all being meticulously catalogued by a devoted staff. There’s a library holding a fraction of what’s still in boxes, a glorious work-in-progress. Mekas talks enough about his own years in Nazi labor camps and displaced persons camps with his brother Adolfas that we sense he’s first and foremost a diarist—he wrote down what he lived, not knowing whether he’d live at all. The memories of diving out a window of his farmhouse into a potato field as Nazi storm troopers pressed guns against his father’s chest, were embedded permanently. And so Mekas, the Brooklyn émigré, quickly became a Manhattanite and began linking the written word with the visual image—as editor of Film Culture (1954), as the first film critic for The Village Voice (1958), as co-founder of the Film Makers’ Cooperative (FMC, 1962), and as founder of the Filmmakers’ Cinémathèque (1964), which would become Anthology Film Archives, in 1970.

During these formative years, Mekas fell hopelessly in love with his first l6mm Bolex, noting he’s worn out five over the decades. While Mekas has been a documentarian—his clips of the original Living Theater production of The Brig, in 1964 sizzle with fury and rage, exactly like last year’s revival by The Living Theater under its original co-founder Judith Melina—he’s largely seen here as a perpetual diarist, shooting everyday events of family and friends (not surprisingly, Mekas is an unabashed fan of YouTube). And so director Workman begins the process of unveiling how Mekas influenced nearly everyone who wanted to be an independent film artist.

“He got excited about leader,” Andy Warhol tells us without a trace of guile. “I mean, he just got excited about leader. And so I decided, if he can get excited about leader, I’ll do leader. And I did a lot of leader.” Critic Scott MacDonald considers Warhol endurance contests like Sleep and Empire with the notion that “the more I thought about [watching a man sleeping for seven hours] or [the Empire State Building through an entire day’s changing light], the more fun it was to think about it.” And this is where Workman really takes off.

We watch clips from beginning films by Orson Welles at 19 and David Lynch at 21, and there are subtle trace elements of what would become Citizen Kane and Eraserhead. Shirley Clark’s stylized views of the Brooklyn Bridge look and sound like that 1961 RCA album by Sonny Rollins, The Bridge, in which he took a year off to practice his horn nightly over the water. Ralph Steiner’s experimental film on water (H20, 1929) has a jolting poetic flair when re-scored by Philip Glass. There’s an exceptionally poignant scene from a 1936 film by Joseph Campbell on the actress Rose Hobart, a brittle beauty who starred with Bogart in the noir Conflict.

And the list goes on: A flurry of pillow feathers fluttering about from Zero de Conduite by Jean Vigo in 1933; Maya Daren’s delicately feminine imagery which is acknowledged as a key early influence on Mekas; Norman Mailer slugging it out with actor Rip Torn in a brawl from Maidstone; distorted views on a woman’s torso (a technique called Rayographs) from Man Ray’s first photo essay; commentary from Pull My Daisy read by Jack Kerouac; snippets from William Burroughs’s Cut-Ups. Workman lays in clarifying voice-overs through all this, aided by film critic Amy Taubin’s helpful comments on images without any clear-cut linear connection. Workman also uses horizontal bands of type moving like ticker tape across the top of the frame to spell out basic axioms of Mekas and others. Some of these are deft and amusing: “I really don’t know what cinema is; we are all at the beginning,” (Mekas)…“I think it’s symbolic of junk,” (Mel Brooks, on The Critic).

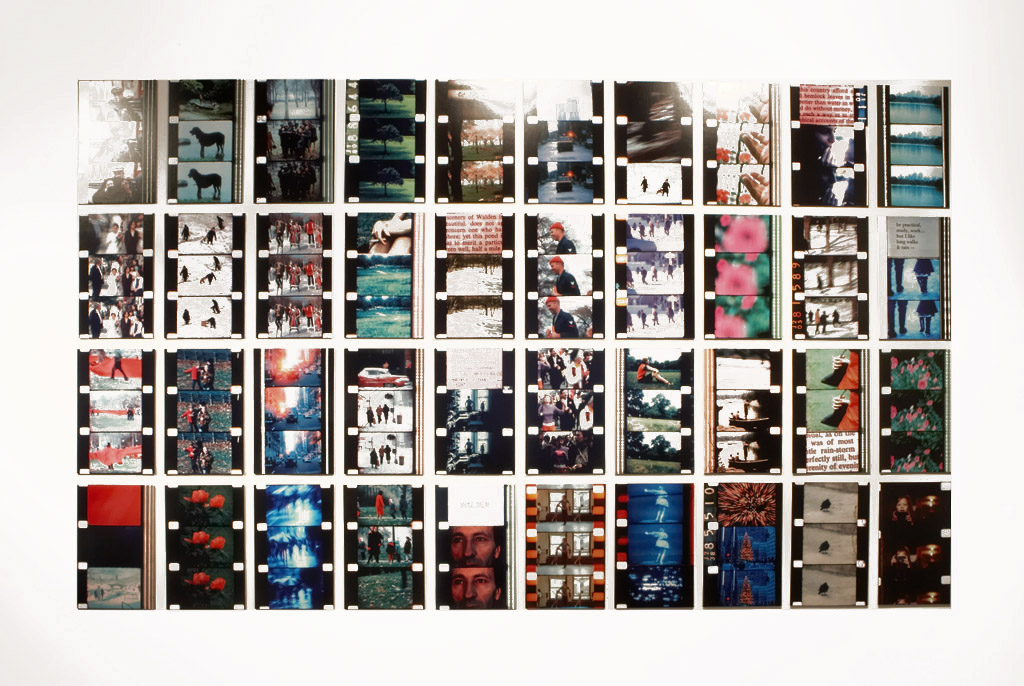

When Workman delves into the better-known classicists of underground cinema—especially Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, and Su Friedrich—he slows the pace, giving both the artist and the work more screen time. Brakhage gives an instructive mini-lecture on the art of camera-panning, and also how we instinctively watch a subject more closely when we turn off the sound on what’s he’s saying. We examine film strips onto which Brakhage has actually glued moth wings and grass. Kenneth Anger—secure along with Curtis Harrington as the most productive LA avant-garde pioneer—discusses scenes from Scorpio Rising and its sequel Lucifer Rising, including the inserts of a Christian pageant play that may have been mistakenly delivered to Anger’s home, which he decided would be ideal in his film. Su Friedrich expounds at length on her relationship with her father, with friends, neighbors, colleagues; she alone goes deep into the frustrations of being an isolated artist. Peter Kubelka lectures on the accidents of filmmaking and spending five years filming an African travelogue for pay. Workman is very good at monitoring our attention spans through all this.

And then there’s Robert Downey, Sr. Father and son bear uncanny resemblances, and we examine how Chafed Elbows and Putney Swope pushed boundaries, beginning the process of insinuating edgy features into mainstream legitimacy. It’s a big treat watching a button-cute Robert Downey, Jr. playing one of the 18 human dogs in Pound. Phil Solomon’s digital video graphic landscapes from Grand Theft Auto push us into the computer graphics of today and seem to echo pursuit clips from earlier eras.

The final scenes of Visionaries return to Jonas Mekas— he’s a cozy grandmaster being lionized by Lola Schnabel over a glass of wine and being toasted by Rajenda Roy, now chief curator of film at The Museum of Modern Art. He seems just as comfortable with the idea of filming his cat eating as he does making 365 short videos (one a day) for Apple computers. The point Mekas leaves us with is that everything he started—the filming, finding the venues to exhibit different new work, establishing the publications and institutions to protect and preserve, were absolute necessities. Absolute necessities. It’s as though if they hadn’t happened, none of this would have happened…and humankind would have gone on living with melodrama alone.