Summer Doc Reviews: Caves, Cowboys and Coke

Cave of Forgotten Dreams

(Werner Herzog. 2010. France/Canada/USA/UK/Germany. 90 min.)

It’s inevitable when you walk into a Werner Herzog film that you’ll be taken somewhere you’ve never been and usually can’t imagine ever visiting. Early on it was Herzog’s adversarial leading man, Klaus Kinski, who did the heavy lifting in the gruelingly unforgettable dramas Fitzcarraldo, Aguirre: The Wrath of God, Nosferatu the Vampyre, Stroszek, and Cobra Verde—many filmed in remote, exotic and unfamiliar locales. Herzog has hauled us to burning Kuwaiti oil fields (Lessons of Darkness), up the peaks of the frigid Patagonia (the little-seen Scream of Stone with Donald Sutherland), and down to the even more solidly frozen McMurdo Station in Antarctica (Encounters At The End of The World). We’ve watched Herzog eat his shoe and viewed the digested remains of two eaten adventurers who got too close to the mammoth Alaskan grizzly bear they were trailing. Herzog’s shorts, features, and documentaries may shock you and disturb you but they’ll never, ever, bore you, even when the director’s lugubrious narrations take on the painful precision of a scholar tiptoeing through broken glass.

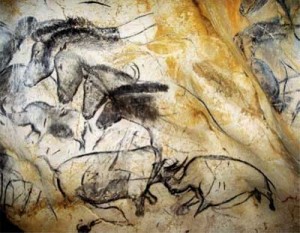

Cave of Forgotten Dreams is the first major feature-length independent documentary filmed in (and mostly released in) 3D. If you haven’t already seen this utterly fascinating exploration of the underground cave art of Charvet-Pont-d’Arc, south of Paris, dating back some 32,000 years, make haste before it slips away—and try to view it in its 3D edition. The third dimension “opens up” a tightly joined sequence of chambers, rock pendants, and walls containing some 400 depictions of 14 species of horses, lions, bears, bison, rhinoceroses, reindeer, and owls, thus giving the true perspectives of a live diorama to the vivid depictions. The Chauvet cave was discovered just 16 years ago after being completely sealed for at least 20,000 years, making it the oldest known decorated cave. There are palm prints that probably were made by the original artist, who may have been accompanied by a second small person, perhaps a child or youth. Next to a bear skull and bones is a rock figure of a bison head atop a human female torso and legs. All of this is sublimely eerie.

Herzog worked with his veteran cinematographer Peter Zeitlinger and a minimal crew in limited light and tightly restricted hours. His two GoPro cameras were taken from their mirror rig and fixed side-by-side on two Manfrotto Magic Arms; Zeitlinger shot from the hip, without a viewfinder. Herzog has often relied on avant-garde scores and composers (particularly Popol Vuh) to underscore the other-worldly mood of his settings, and here Ernst Reijseger layers in ethereal choruses that give the work a stately cohesiveness.

In Frederick Ott’s definitive 1986 book, The Great German Films, Werner Herzog observed, “We are surrounded by worn-out images, and we deserve new ones, I see something on the horizon that most people have not seen. I seek planets that do not exist and landscapes that have only been dreamed.” In Cave of Forgotten Dreams, this master filmmaker may have found his most original and profound landscape.

Buck

(Cindy Meehl. 2010. USA. 88 min.)

The horses shown in stark, tight profile in Herzog’s Chauvet cave are wild and untamed, and their charcoal renderings have a palpable, distressing urgency. They seem to want to burst their bounds, and Herzog’s 3D cameras lend them a lifelike presence. Cindy Meehl’s moving portrait of a modern day gentleman horse trainer, Dan “Buck” Brannaman, is the flip side of the coin—a documentary that demonstrates how “natural horsemanship” as taught by Brannaman in clinics 40 weeks a year, can gentle nearly all volatile colts and stallions, winning their trust with a loving voice and manner that can work down to a whisper. This is the literary backdrop of The Horse Whisperer, Nicholas Evans’s 1995 novel that became Robert Redford’s 1998 narrative film, in which Brannaman both doubled Redford and served as the drama’s key equine consultant.

Brannaman, who’s a trim, relaxed 50-year-old, grew up in Montana and Idaho in the 60s. He and his older brother were trained up by their dad as “Buck and Smokie, The Idaho Cowboys,” working the rodeo and county fair circuits as trick rope performers. Their father is the grim, violently abusive shadow presence that Buck the movie slowly unpeels like layers of an eternal sore that will never quite heal. By demonstrating in great detail how Brannaman has dedicated much of his life to treating his own childhood wounds—making sure no horse around him is ever mistreated—Meehl’s film becomes a careful, responsibly shaped mix of dread and kindness. It’s a mirror into a cowboy’s soul, but it’s also a glimpse into his father’s brutal countenance, sometimes hidden behind sunglasses, and appearing to have been a soulless monster. Buck thus has a tension that’s never wholly resolved today, even though Brannaman has a loving and devoted wife, a supportive daughter who rides and ropes with him, a wonderful foster mother, unending friends and admirers, a 1,200 acre ranch in Wyoming, and all those well-cared-for horses that seem to sense and seek his abiding presence. We can’t see Brannaman’s childhood scars, but the filmmaker makes clear that Buck still carries them, lightly, perhaps in the laureate with the tiny red flag that he uses to ease and maneuver his horses. Make no mistake, Buck is a feel-good doc… but one that keeps looking back over its shoulder.

Hit So Hard: The Life and Near Death Story of Patty Schemel

(P. David Ebersole. 2010. USA. 103 min.)

Talk about carrying your support group with you. When Patty Schemel, the former drummer in Courtney Love’s alternative band Hole, came to the premiere of the documentary on her rocky life and times during last March’s New Directors/New Films, she brought along many of the good influences in her life. Let’s see, there was her mom, her brother, her wife (producer Christina Soletti), their baby (Beatrice), her director (P. David Ebersole), his husband and co-producer (Todd Hughes), plus Hole’s former lead guitarist Eric Erlandson (the latter chap decidedly not a good former influence).

At 44 and with six years sober, Patty lives in LA and runs a dog walking/shelter service and stays busy occasionally drumming and giving lessons to teen girls. She’s modest, low-key, and solid—a survivor who was once a cross-addicted alkie/junkie. Hit So Hard starts as an unruly mix of home movies of the band working and playing, including Courtney’s husband Kurt Cobain and her bass player Kristen Pfaff (both died within months of each other in 1994). Patty is shown as a rock-solid percussionist who little by little goes down to booze, cocaine, and heroin. The footage is harrowing and the talking heads—female drummers from Fanny, the Beastie Boys, and the Go-Gos plus Dallas Taylor of Crosby, Stills and Nash (and now a substance abuse counselor) and Roddy Bottum from Faith No More—help chart her losing struggles. It takes Patty a long time to hit bottom, living in a culvert under a bridge, and the audience stays hushed through these scenes because they’re safely glimpsing the hell that survivors in recovery talk about every day.

Hit So Hard has scenes of Patty sober for two, three, four, and five years, and they’re vivid comparisons with her days drinking and using when we observe she could barely put two coherent sentences together. Has sobriety tamed her? Sure—but any kid who started out at age 15 pounding drums in a band called Kill Sybil is not about to go gently into the night.

With a distribution agreement in place, this keenly observed film stands apart from a number of other worthy rock docs similarly honored at festival screenings that are still looking for a distributor. One is Squeezebox (Tribeca 2008 premiere), Steve Saporito and Zach Shaffer’s teardown record of the pansexual rock club at Spring and Greenwich which was home from 1994-2001 to a slew of gender-benders from Karen Black and Jayne//Wayne County to The Toilet Boys and Wendy Williams and the Plasmatics. A second is Mandy Stein’s Burning Down the House: The Story of CBGB (also premiered at Tribeca, in 2009), an affectionate look-back anchored by Jim Jarmusch and Luc Sante at the Manhattan rock club and its tireless proprietor, Hilly Kristal, that gave more start-up bands their first 15 minutes of fame than any other—the film is filled with artfully chosen moments from Suicide’s Martin Rev wandering offstage in the middle of a set to take a phone call, to juicy comments from the plumbers ripping out the urinals in CB’s basement hellhole of a bathroom. A third is God Bless Ozzy Osbourne (Tribeca again, 2011), Mike Fleiss and Mike Piscitelli’s blistering, take-no prisoners chronicle of the Prince of Darkness (produced by Ozzy’s son Jack), with a redemptive and moving final half hour of how Oz has stayed clean, reconciled with his wife and children, and clearly has found a Higher Power he communes with alone, before every concert. And a fourth is Roddy Bogawa’s Taken By Storm: The Art of Storm Thorgerson and Hipgnosis (premiered at South by Southwest, 2011), a portrait of Thorgerson, the feisty, free-wheeling 67-year-old founder of the British design firm Hipgnosis that created iconic LP covers for Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Peter Gabriel, and countless other rockers for decades.