New Directors/New Films 2020 (Dec. 9-20)

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw selects 49th edition (virtual) favorites

Do you remember the last movie you saw in a real theater, up on a big screen? Our memories grow more remote by the day. For this viewer it was a screening of the sumptuous 150-minute Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains. Directed by Gu Xiaogang, Dwelling is a multi-generational family saga that slowly unscrolls as the camera leisurely journeys, hour by hour, season by season, up and down China’s Yangtze River, pausing to disembark and eavesdrop on unending inter-generational squabbles. It ended late Friday afternoon, March 13, just as the Museum of Modern Art was closing its doors and effectively shutting down New Directors/New Films before it ever opened.

Nine months have passed, and ND/NF, co-sponsored by MoMA and Film at Lincoln Center, has just fulfilled its promised schedule, updated to 24 features and 10 shorts, all online. (Dwelling, though still an official selection, did not participate in FLC’s Virtual Cinema.) The festival continues its mission of “representing the present and anticipating the future of cinema, celebrating filmmakers who push the envelop in unexpected ways.” New Directors has introduced work by Steven Spielberg, Chantal Akerman, Spike Lee, Kelly Reichardt, Christopher Nolan, Mia Hansen-Love, and Hou Hsiao-hsien—to name a few. Back then they were barely known. Joining their ranks is Sonia K. Hadad, a 29-year old Iranian filmmaker who earned her MFA in Cinema and Fine Arts at Emerson College in 2017. Her edge-of-the-seat 15 minute short, Exam, gets pride of place in critic’s choices:

Exam; Sonia K. Hadad; Iran; 2019; 15 minutes

The most memorable shorts are often packed with surprises. Yet you can often summarize their core premise in one sentence. Try this: “Middle-class Iranian teenager tasked by her dad to make a cocaine delivery, hidden in her backpack, gets to her all-girls’ class and the principal walks in, ordering a bag check.” Yipes. There are 1,001 possible ways to script out this scary premise, and Ms. Hadad, a 29-year-old Iranian writer/director with a 2017 MFA from Emerson, will hold you out the window as you wait to see which one she’ll invent.

Every second of Exam is crafted to convey urgent information. At the family’s breakfast table, cramming for an exam and stuffing a cheat sheet up her sleeve, the girl (Sadaf Asgari) is given an order by her offscreen father: “Farid just called, I’ll give you a package to give to him. He has a customer today, I’ll prepare it for you.” She’s told to wait on a busy corner for the contact. When the contact doesn’t show, the girl heads into her exam.

In class, the girls are taking their test when the school’s administrative head (Hadis Miramini, as severe a disciplinarian as Agnes Moorehead or Judith Anderson ever played), walks in and orders a bag check. She’s looking for banned cell phones, cigarettes, hair dye, and other no-no’s. The girl is thinking about the little packet of hard drugs resting between her phone and her pens, in the backpack on her lap. She manages to maneuver the packet out and into the top of her boot. But it falls out. She slides it under her boot. “Lift your feet” orders the head.

This sequence and what follows are a demonstration of acting artistry, editing, and sound design—a throbbing electronic chord that steadily builds—that convey a sense of dread you’ve (hopefully) never experienced in a classroom. This is what movies do when everyone is bringing their A-game, making magic. Kudos to DP Alireza Barazandeh, editor Ehsan Vaseghi, and Ms. Hadad’s co-writer, Farnoosh Samadi. As the girl, who’s onscreen every moment, Ms. Asgari shows a silent cunning beyond her years, mixed with palpable terror, that’s already won a Special Jury Award for acting at this year’s Sundance festival. Exam gets an A.

Two Of Us; Filippo Meneghetti; France/Luxembourg/Belgium; 2019; 95 minutes

Meneghetti’s drama is as old as the 50s and 60s lesbian novels of Ann Bannon and Marijane Meaker, yet a finely machined ensemble of four perfectly chosen actresses fill it with fresh, tingling, immersive life.

It’s set in Paris and the time frame is indeterminate, though no one is using mobile devices and there’s a turntable in the top-floor apartment shared by Nina (Barbara Sukowa) and Madeleine (Martine Chevallier). Both women are in their 70s and each has maintained separate identical residences across the hall from each other. They’ve hidden their secret love not so much from society as from Madeleine’s deceased husband, her divorced daughter Anne (Lea Drucker), Anne’s brother and her grandson.

As you’d imagine, the powerhouse Sukowa makes Nina the dominant partner, and their shared love is a fully committed and eternal passion. Nina has persuaded Madeleine to sell her apartment, realtor-appraised at $250,000, so they can move to Rome, where they first met. All Madeline has to do is tell her family. But Madeleine can’t—she won’t break her daughter’s heart, a daughter who believes “mom sacrificed herself all her life for her family.” So Nina throws a hissy fit and storms out. And Madeleine suffers a stroke, which leaves her in a wheelchair unable to speak or move.

At this point, Two Of Us shifts gears into a subtle, tense and escalating tug-of-war between Nina and Anne. Taking charge, the steely, protective daughter visits her mother every night after her work in a hair salon. Anne hires a live-in caregiver, Muriel (Muriel Benazeraf, perfectly cast as the efficient but chilly aide who’s thrilled to have a paycheck). Nina, frustrated and furious, confident she can restore her lover’s speech and body, plots to insinuate herself back into Madeleine’s life without revealing her true identity to either the daughter or the aide. She offers to pay Muriel her salary (a big mistake) to stay the hell out of her way. The incidents grow sharper, as the daughter gradually, then suddenly puts together her mother’s secret life. Desperate to protect mom, Anne fires Muriel, changes the locks on Madeleine’s apartment and has her mother committed to a hospice. Will Nina ever give up trying to reunite with her partner?

Two of Us, Menegretti’s second feature, is already France’s official Oscar entry. It’s a twisty, fully-assured movie movie, the kind of workmanlike romance Douglas Sirk piloted for Universal in the 50s, and that Todd Haynes sometimes updates for today’s audiences. It bears favorable comparison with Carol, Haynes’ lush adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt, as well as Sarah Polley’s Away From Her, adapted from Alice Munro’s “The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” in which Julie Christie loses her struggle with Alzheimer’s disease.

We’ve grown up in the dark with Sukowa through the latter decades of the 20th century, watching her build her chops under formidable directors like Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Margarethe von Trotta, recently playing Hannah Arendt. She’s a conniving, volatile, take-no-prisoners actress with a Plan B always at her fingertips. Chavallier, by contrast, a veteran of France’s Comedie-Francaise, knows a lot about acting with just her eyes. We watch her register nuances of emotion the way we watch everyone’s masked-up eyes these days—Chavallier pours out volumes of emotions that eyes alone can communicate. All praise to the sturdy support of Ms. Drucker’s Anne and Ms. Benazeraf’s Muriel, both essential to keeping this heartbreaking drama from sliding into facile melodrama. Two Of Us is a weepie, but don’t let anyone tell you a good cry at the movies isn’t good for the heart.

The Fever; Maya Da-Rin; Brazil; 2019; 98 minutes

“I can easily drop a new film after only five minutes of watching, then I’m done with it. If the first five minutes aren’t right, it cannot become a good film.” You’d be surprised how many film critics agree with this stern criterion by Hubert Bals (1937-1988), founder of the Rotterdam Film Festival. Bals was a ferocious champion of dramas from emerging countries, and a stickler for precise, formal cinematography. The Hubert Bals Fund, launched in ‘88 to honor and continue his search for “work steeped in local flavor and rooted in the country where it’s made,” is a prime backer of Da-Rin’s first dramatic feature, as well as two other dramas in this edition of ND/NF.

It’s useful to note the longest picture supported by the Bals Fund, shown in New York in a major festival, was the 14-hour Argentinian opus, La Flor, a critic’s choice in the 2018 New York Film Festival. La Flor followed a quartet of feisty superwomen backward in time through their country’s cinematic history, all the way back to Argentina’s silent era. That picture didn’t really begin until about eight hours in, when it finally abandons its pulpy contemporary roots and restarts itself in the 1940s. (So much for Bal’s first-five-minutes theory.)

The Fever is on point from its opening frames. Like many memorable independent films that explore how a people and a culture migrate from a traditional to transitional society, it concentrates on one figure: Justino (Regis Murupu, a real-life member of Brazil’s indigenous Desana peoples), an armed daytime watchman on the industrial docks of Manaus, a sprawling port city facing the Amazon rainforest. His job is monitoring giant cranes that lift shipping containers the size of boxcars, full of industrial parts, out of tankers and lower them onto 18-wheelers. Justino’s been doing this since he put down his handmade hunting tools and walked out of the jungle 20 years ago.

He’s aged in place, losing a wife to illness as he watches a daughter, Vanessa (Rosa Peixoto) preparing to leave for medical school on a scholarship. Justino helps support her and a grandson in a modest but poor section of Manaus. Everyone in the household speaks their native Tukano language. Justino is living out his life—waiting out might be more accurate—in his own existential limbo, still sleeping in a hammock as he did as a youth. And then he comes down with a fever.

The script (by Da-Rin, the Portuguese filmmaker Miguel Seabra Lopes and anthropologist Pedro Cesarino) layers in Justino’s approaching crisis in small, spare measures. The corporation’s white HR lady admonishes the guard for nodding off. Another watchman, his night counterpart, is a white racist who baits Justino with memories of working on a farm “with Indians, real ones with arrows and sticks.” Justino’s older brother visits and implores him to return to their village, where he won’t have to eat the white man’s food and where a shaman will look after his fever. On top of all this—and here’s Da-Rin’s most ingenious plot device—the television news carries reports of some kind of forest creature that’s roaming the city, slaughtering domestic pets. At night when the bus drops him off, Justino senses something stirring in the adjoining woods. Eventually it will chew its way through the dockyard’s thick wire fence.

The Fever holds your attention as it builds your interest in this stoic middle-age watchman. It’s a story that unfolds with the same patient grace and exactitude that Justino demonstrates in improvising a tale for the grandson on his lap. Da-Rin’s subplot on the killer that’s stalking Manaus is the frosting on the cake. Justin’s hunt by moonlight for the city’s nocturnal creature bears an uncanny resemblance—in mood, tonality and ambient sound—to Jacques Tourneur’s creepy 1943 thriller, The Leopard Man. Little wonder Da-Rin researched and planned her movie for six years. It shows so well.

Nasir; Arun Karthick; India; 2020; 80 minutes

Narrative dramas of working families in far away lands, like The Fever and Nasir, have been a staple for curators at MoMA and FLC for nearly half a century. Films from India first got credentialed in New York City when MoMA premiered Pather Panchali, the debut film by Satyajit Ray, in 1955. (Your critic watched it three years later at the University of Wisconsin, reviewing it for the student newspaper as “a striking study of the intimacies and pathos of family life” in a cruel, often brutal society.) It was the first of a landmark trio of Ray films, collectively known as the Apu Trilogy, all based on Bengali tales of the 1920s and 30s.

Writer/director Karthick adapted Nasir for the screen from a 2012 short story, “The Clerk’s Tale,” by Dilip Kumar, who runs a bookshop in Chennai. Kumar and co-scripter Kartnick guide us through one workday of a Muslim clothing shop clerk, Nasir (acted with poise and grace by Koumarane Valevane, a professional theater director). Nasir, his family and their traditional Muslim community are attuned to how Hindu extremists can, without warning, lay siege to Muslim shops throughout the city of Coimbatore (where the drama is set and shot) and much of southern India. Yet for most of its 80 minutes, the threat to Muslims is only hinted at, much like the jungle menace in Brazil.

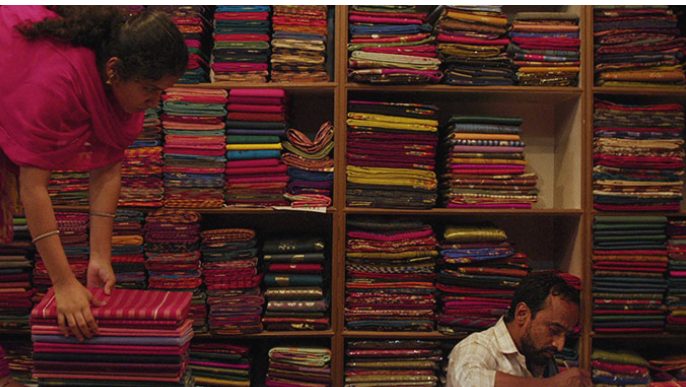

Like his counterpart in Manaus, Nasir has a long list of family responsibilities he’s learned to handle. His mother is slowly failing with cancer, his adopted son has severe mental challenges, his boss won’t give him a raise. At least he doesn’t have a fever like Justino. Nasir wakes at 6:00 am, pumps water for showering and cooking from a neighborhood well, hugs and teases his wife Taj (played by Sudha Ranganathan, another fine pro), ponders his first cup of tea and first cigarette, packs his sandwich from a street vendor, and accompanies Taj to a bus stop. Nasir is one of several congenial salespeople in a shop specializing in colorful saris and shirts of every size and shape, comfortably tucked in a traditional Muslim community. The sales goal each day is selling one percent of the stock. The staff’s amiable chatter offers select glimpses into how life is lived in a community that hasn’t changed much since the 1950s. On his lunch break, Nasir composes love poems to his wife. In his way, he’s a charmer.

Out of twenty new features presented in this festival, it’s unlikely one would come upon an Indian drama and a Brazilian drama so similar in confident narrative structure and rare production excellence. They’re both triumphs of simple, exquisite storytelling, and both have conclusions that are profound and unsettling. Like The Fever, Nasir mixes in a lot of non-professionals, as Satyajit Ray’s early films did. Karthick shoots in standard-screen ratio, in 16mm color that produces a softly muted palette that lovingly brushes-and-combs the shelves of saris and even the mannequins Nasir fusses over.

The clerk is at home here, and when the shopkeeper tasks him to deliver a bag of blazers to college students in big city apartments, we sense his unease. He’s not used to bolted urban doors that open to blaring rock and hostile stares, and neither are we—the director has effectively sealed off his affable clerk and family from India’s modern world, at least for a while. It doesn’t come as a surprise that Nasir received financial support from the Hubert Bals Fund.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 30th annual New York Jewish Film Festival, co-sponsored by The Jewish Museum and Film at Lincoln Center, showing virtually January 13-26, 2021.

Regions: Brazil, France, India, New York City