Rendez-Vous with French Cinema, March 4-14

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw welcomes four virtual signs of Spring, all with surprise endings (no spoilers!)

Spring is busting out all over New York City, with cinemas scheduled to open March 5 (25% capacity, 50-seat maximum). Online, Film at Lincoln Center and UniFrance are showcasing 18 new vital and vibrant examples of contemporary French filmmaking. The 26th annual edition includes new work from returning filmmakers plus six debut dramas. All 18 features are available in the FLC Virtual Cinema, and include virtual Q&As plus viewer participation in the second annual Rendez-Vous Audience Awards. Finally, a selection of fest titles are available for virtual bookings at select arthouses across the U.S., as part of the inaugural A Taste of Rendez-Vous program.

One striking consistency in this year’s menu are dramas with surprising and unexpectedly moving conclusions. Through the years, so many Rendez-Vous’ selections have been invigorating experiences, no matter how they end—but to discover four that leave you examining their aesthetics with a sense of wonder, for days after, is un regal agreeable for cineastes. It’s a sure sign we must be turning the page into a new season.

A l’abordage!; Guillaume Brac; France; 2020; 95 minutes

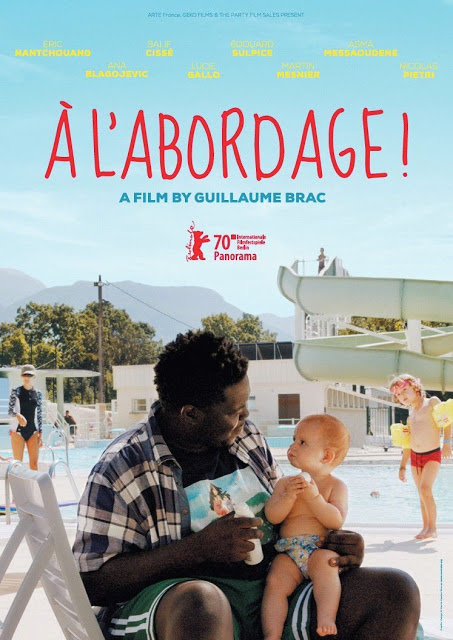

Movie producers try early on to identify and select the one image in their films that will most likely appeal to audiences. This often becomes the poster for the movie, long before it’s seen by the general public, including film critics. It’s no spoiler to direct your attention to the young man, Cherif (Salif Cisse), seated above on a blanket, being watched by an adoring baby who is the scene-stealer of this entire festival.

Nor is it giving away too much if you know the picture’s title is a sly reference to an ancient cry by pirates just before they boarded a ship they wanted to capture. So the beckoning puzzle of this deftly appealing tale is how the title and poster image (shown here) are connected. Ah, these French.

The plot follows Cherif and his assertive and boisterous student pal Felix (Eric Nantchouang) from the moment Felix meets another young Parisian, Alma (Asma Messaoudene), at an outdoor dance. They innocently chat away the night and then Alma returns to her family, who are vacationing in a southern village. Felix, smitten with a passion he thinks Alma’s on the verge of reciprocating, decides to pursue her to her family’s vacation hideaway. Cherif, having no girlfriend, agrees to tag along. They get a ride with another French youth who’s turning mom’s car into a car service. Arriving in the family’s picture-postcard village, there’s a fender-bender and mom’s car has to be towed in for repairs that will take days. Everyone (and the movie) seem stuck.

At this point, director Brac’s screenplay (co-written with Catherine Paille) is so breezy and inconsequential, you may find yourself sitting on your hands. We observe that Cherif and Felix are Black, and that nearly everyone else in the picture including Alma, are white, but this appears of no interest to anyone. We also get the idea that the boldly confident Cherif would like to pirate Alma away from her family, at least for a day and hopefully a night, but this doesn’t appear likely, as the young woman is positioned as moody, high-maintenance and subject to panic attacks (especially in the biking exploration shown here).

Felix and Alma’s unsatisfying encounters are intercut with the more sedentary Cherif, who’s become casually acquainted with Helena (Ana Blagojevic). Her husband is away attending to an emergency at a pizzeria he runs in Lille. She’s in charge of their infant daughter, Nina (still awaiting her first on-screen credit). Cherif becomes the baby’s pal and occasional sitter while Helena goes for a swim. It seems she and Cherif grew up in the same town. “My thing has always been a basketball hoop and computers,” he shyly tells her. “Maybe the idea of a restaurant and a baby the same year wasn’t the best idea,” she ruefully admits. He’ll politely ask her if she’d like to come to a cafe with him for a beverage. She agrees only after she’s found a reliable sitter. What happens that evening is something neither Helena nor Cherif ever imagined would take place.

Director Brac and a buoyant cast—especially Salif Cisse whose soulful portrayal of the soft-spoken Cherif is like unearthing buried treasure— have created a movie that may steal hearts away.

The Big Hit; Emmanuel Courcol; France; 2020; 106 minutes

One of the biggest hits in prison populations worldwide, for decades, has has been Samuel Beckett’s existential classic, Waiting for Godot. Beckett wrote it it 1948, living in Paris in a home overlooking the exercise yard of the 1867 high security La Sante prison. Godot has been performed in English since 1957. There are two backstories to The Big Hit, the first of which is being freely shared here in the hope of persuading you to make haste to view Courcol’s smashing powerhouse of a movie. The second backstory, part of which informs Courcol’s drama, needs to be held for your personal viewing pleasure.

In 1957, a kidnapper and armed robber, Rick Cluchey, serving a life sentence in California’s San Quentin, heard a PA broadcast in his cell. It was an Actors’ Workshop production of Godot, being staged in the prison’s dining hall. He identified immediately with the characters—most especially a warden-like figure dragging a prisoner-like figure, around on a rope. He also empathized with the play’s core concept of eternally waiting for someone or something that never arrives. Cluchey formed a prison workshop dedicated to performing Beckett’s works, restaged Godot using his fellow inmates, wrote his own plays, eventually had his sentence commuted by California’s governor, and went on to tour Godot across America. He acted in productions of other Beckett plays, directed by the playwright himself. Cluchey’s own life found salvation, and purpose, through theater. His own life was dramatized in the 1987 film Weeds starring Nick Nolte.

The Big Hit is only Courcol’s sophomore feature as a director; he’s best known throughout France as a veteran stage actor and writer. His strategy is arranging (and rearranging) several layers of inspired-by-true-events drama in arresting new patterns. Etienne (Kad Merad, in, as they say, a career-defining performance) plays a mostly out-of-work actor and divorced dad who’s turned to directing plays in prison to pay his daughter’s tuition. He’s tough and grizzled, prepared to the teeth, endlessly supportive and patient. It’s a thankless job but he’ll give it his best shot. Etienne intuits how Godot could work for a company of incarcerated men. Neither the inmates nor warden Ariane (Marina Hands) show much interest, though the play is easily performed on a bare stage with minimal props and simple costumes.

The picture works in ways that steadily build interest in the 1,001 steps of process. We watch a play being assembled with a mostly unwilling and unstable cast. Stubborn resistance melts into curiosity and slow identification with Beckett’s broken characters. Courcol whips the pace and editing along at a furious clip, and a superb ensemble cast jackhammers a script that’s built like the best of Aaron Sorkin.

The director’s wisest decision was casting skilled professional actors, rather than trying to train up amateurs for a movie production with a limited budget and shooting time. (Paolo and Vittorio Taviani did the opposite in 2013, filming a production of Julius Caesar in Rome’s Rebibbia prison with real inmates, with decidedly mixed results.) Waiting for Godot comes to dazzling screen life before an audience of prisoners’ loved ones and friends. The question immediately arises: What if the director and his players doing time could get the warden’s permission to do some of that time on a bus tour of Godot?

There’s a lot more to unpack, but not in this review. Put The Big Hit on your must-see-for-big-surprises list.

Final Set; Quentin Reynaud; France; 2020; 113 minutes

With his shaggy hair, chiseled features and trim frame, actor Alex Lutz can’t help but remind you of Bjorn Borg, the first tennis player to win six French Open singles titles. Up close, Lutz also boasts a smidgen of Klaus Kinski, lending his concentration a hint of maniacal menace. Lutz never held a tennis racket before preparing to play Thomas, at age 36 a past-his-prime pro with 18 years on professional courts. Thomas is determined to launch his comeback in the qualifying rounds of the French Open at Roland-Garros, the premiere clay court in Paris. Lutz trained four hours a day for four months to play Thomas, and he sure looks and acts like the real deal (a pro, Frederic Petitjean, doubles him in long shots and some ground level sequences shot from behind). This is sports movie magic at its pinnacle.

It’s also a familiar, family-friendly race-against-the-clock drama, in which you’re constantly weighing the assets and liabilities of a tennis pro who’s trying to outrun his biological clock. On the plus side are a supportive wife, Eve (Ana Girardot), button-cute son, and doting mom (Kristin Scott Thomas). His wife was once a known name on the club circuit, and mom runs a profitable tennis camp and helps keep her grown son debt-free. Thomas has picked up a commercial sponsor, a line of fragrances that pays him handsomely to wear its signage. He’s a good dad, coaching his boy’s athletic teams when he’s not traveling on the tennis circuits, which is more and more of the time. His family life is a priority, right behind his first priority which is staying active on the courts.

The minuses pile high and deep. One knee is increasingly deforming from ligament lesions, and arthritis is weakening his knee joints. His serving hand is starting to bleed. The press weighs in, describing a “brilliant, erratic career, returning from oblivion at almost 37.” The car that used to drive him to matches is now “reserved for the top players,” and his former driver is starting to bet against him. A potential opponent, the up-and-coming 17-year-old Damien (a peppy Jurgen Briand), calls him “my grandma’s favorite player.” But maybe what concerns Thomas most is watching a late night telecast of Lonely Are the Brave, a 1960s movie with Kirk Douglas acting the last dying cowboy, his face masked in pain. Just as Douglas’ character only knew how to be a cowboy on a horse, Thomas only knows how to be a tennis player on a court.

Still and all, he’s determined to conquer all five qualifying rounds. And we cheer him on, even as he sags to the ground at the end of round three. A lifetime of movies have aligned us with courageous, likable underdogs, come what may. We sense going in that Damien, the new wunderkind, pointing his finger at Thomas from a life-size cardboard cutout in a sporting goods store, may end up as Thomas’ ultimate opponent in round five. And won’t that be something to watch—this treetop tall kid versus the shrinking old man!

Like Courcil in The Big Hit, Final Set’s director, Quentin Reynaud punches up all the right buttons—glossy lensing, razor-sharp editing, an elaborate production including larger and larger banks of spectators without the cardboard figures we’ve been watching in outdoor sports seats, a pulsating music score that underlines every whack and grunt. Alex Katz, matching Kirk Douglas in Universal’s seminal urban western, has a screen filling face that’s built to exude unending suffering and endurance. He, too, is one of the lonely and the brave. He can take a lickin’ and keep on tickin’. And Reynaud gives him a final set that’s one for the heart.

Should the Wind Drop; Nora Martirosyan; France/Armenia/Belgium; 2020; 100 minutes

You’d think any remote region in the world eager to establish its global presence would be thrilled to have a full-length feature, entirely set and shot there, chosen for the Cannes festival. Yet just as Nora Martirosyan’s debut feature —a stunning drama she describes as “an archive of a country under threat of disappearing”—was about to open last fall at Cannes, Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Culture sought to ban its festival showings in both France and Estonia. Neither fest caved, and Should the Wind Drop became the first Armenian film since 1965 shown at Cannes.

There’s a torn-from-the-headlines history here worth summarizing (but no spoilers). Martirosyan, a painter raised in Soviet Armenia, first visited the mountainous regions of Nagorno-Karabakh in 2009. She’d written and directed shorts and was searching for a subject for her first feature. In particular she was drawn to Stepanakert, a small but modern capital city tucked at the foot of the eastern slopes of the barren Caucasus Mountains. The city and its airport are flanked by Russia, Iran, Georgia and the Caspian Sea.

In particular the artist was fascinated by the airport, a strikingly contemporary structure designed like a winged bird. Over many visits and the scripting of her film with novelist Emmanuelle Pagano, she absorbed the lessons of a six year war in the late 80s and early 90s between Armenia and Azerbaijan, in which 30,000 lives were lost. And she discovered their continuous boundary conflicts had kept planes from ever landing or taking off from the airport. On many world maps, the capital of this tiny republic was starting to vanish. Martirosyan had found her subject.

As her film was premiering this past November, weeks of bloody conflicts had renewed between regional peoples. And so Should the Wind Drop—which references wind sheer, the height of surrounding hills, and the aerial space required if an approaching plane veers off-course and needs to circle for a second approach—is worlds above most inspired-by-true-events dramas. It’s a startling reflection, infused with tension, in which illusion tags along beside a real life culture in real time collapse.

The plot follows Alain (Gregoire Colin, taciturn and measured), a French auditor whose job is appraising whether the airport meets international aviation standards. The airport’s executive director is eager to win approval.His staff and air controllers would love to see planes landing from Moscow and departing to Paris. Local journalists are standing by to cover a go-ahead. But when Alain starts measuring and calculating the actual geo-boundaries that separate the warring neighbors, he finds discrepancies. Fuming, the exec director, who lost relatives in the 90s genocide, declares “nothing is less neutral than Google Earth.” Alain’s interim report to his French superiors express doubt on any plane being able to fly safety in and out of Stepanakert.

Moreover, as he observes the families who graze sheep and goats in the surrounding hills surrounding the airport, Alain is struck by one young boy, Edgar (Hayk Bakhryan, a perfect discovery), a water bearer who sells to surrounding rural homes and vans of traveling soldiers. Edgar thinks he should hold onto the land that’s been left to him. Yet he’s learned to play war games with other boys, who set smoky grass fires that would make takeoffs or landings impossible on the nearby lighted air strips. When Alain decides to visit the border at night to further evaluate cease-fire terms that may have been compromised by military authorities, he’s stepping into real danger.

Confidently photographed, smoothly and sensitively edited, and braced by a music score that insinuates itself like a coiled serpent, Should the Wind Drop has its own magical surprise ending. It’s the one place where Martirosyan paints a purely aesthetic judgement. And it makes this journey into what an exotic 1948 song, “Faraway Places” called “faraway places with strange-sounding names…are calling, calling you” more than worth your while.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s selections in the 20th annual Tribeca Film Festival, June 9-20.

Regions: France, New York City