Dale Bell’s “Woodstock”

Senior critic Kurt Brokaw reflects on the 1969 concert in print and film, and previews a massive Central Park celebration August 21

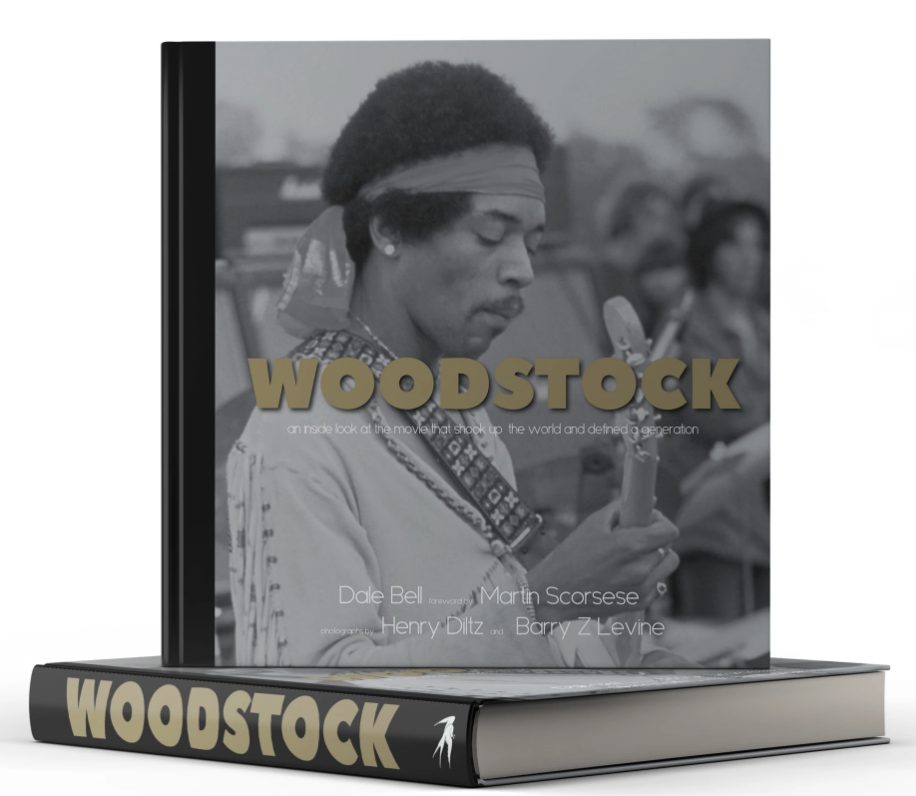

Dale Bell’s Woodstock (Rare Bird Books, 2019) is a day-by-day, event-by-event diary by Bell, the associate producer, and 22 other professional volunteers who put together the Oscar-winning Best Documentary of 1970. As Martin Scorsese writes in a brief forward, “the second half of the 1960s is the only time I’ve ever heard people talk about love in serious terms.” Their recollections, combined with the intimate black-and-white and color photography of Henry Diltz and Barry Z. Levine, capture the doc that captured “three days of peace and music” (August 15-18, 1969) in a cow pasture in upstate New York with a mix of fondness, passion, back-stage intimacy, and awe.

“Start filming what interests you. Turn off when it gets boring,” was the sole instruction given by the lead cameraman to the crew operating 15 portable Eclair NPR 16mm film cameras. Bell also hauled up three Bolex cameras, three Arri S cameras, four body braces (pre-Steadicam) designed by director Michael Wadleigh, seven Nagra tape recorders, 350,000 feet of raw stock, 400 rolls of 313 3M quarter-inch audiotape, ten still cameras, three tents and 12 sleeping bags. 75 chickens—cut, cooked and wrapped—got forgotten. 30 rolls of raw stock were delivered two days after the festival.

The sound, which also received an Oscar nomination, was directed by a gentleman who kept asking “Is Joe Cocker spastic or something? What’s wrong with his voice?” The editing, which received a third Oscar nomination, was headed by world-renowned Thelma Schoonmaker. She and Scorsese, both assistant directors as well as cutters, were warned by a Warner Brothers marketing executive about their shot selections of some of the 450,000 attendees who stripped for swims in a nearby lake: “One hard-on, and you get an X.”

Warner bought the film rights from Atlantic. Ahmet Ertegun, the label’s founder, was really only interested in footage of Atlantic’s three acts that performed. Bell, a former New York public affairs journalist who lived overlooking the Hudson, hand-carried the first 185-minute print to the Trans Lux theater in Manhattan for its premiere, hardly imagining it might eventually gross $34M, in that era the highest earning doc ever made. (Today it’s #31.) A director’s cut in 1994 expanded the running time to 224 minutes.

Bell’s handsome book is must reading for every student and fan of documentary film-making who’s forever humming some crazy tune.

Concertizing in a World Without Devices

Documentary fans and The Independent have already discovered the urban alternative to the upstate ‘Woodstock Nation’ in July/August, 1969: the concerts held and filmed in Harlem’s Marcus Garvey Park. These six weekends of lost performances—including one day of simultaneous sets in both venues, August 15— were first uncovered in the Westchester basement of the original producer (the late Hal Tulchin) in 2003 by archivist Joe Lauro, head of Historic Films. The metal cans of film made their way through many interested producers into a team that chose Ahmir Khalib Thompson to lead their project. For his directorial debut, Questlove artfully rearranged and sequenced the performers into an indelible history of 20th century Black music, Summer of Soul.

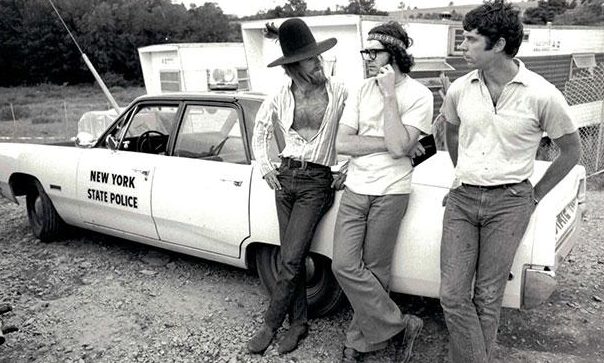

If you page through Bell’s book and watch the docs of Woodstock and Summer of Soul, you’ll be struck by their absence of modern technology. There are no cell phones, texts, tweets or drones, no social distancing, no rain dates, no VIP seatings, no corporate intrusions—not even any tickets being collected at Woodstock once a few flimsy fences came down. While street corner pay phones abounded in Harlem, few portable phones ever arrived in farmer Yasgur’s pasture. Walkie talkies and two tireless MCs (the Parks Department’s Tony Lawrence on the Harlem stage, lighting designer Chip Monck at Woodstock) were the primary links between audience and performer. This worked fine for your critic, then the 31-year-old creative director of RCA Records, on-site at Woodstock primarily to deliver urgent cover art to the Jefferson Airplane. By the time Jimi Hendrix delivered his spellbinding rendition of The Star Spangled Banner and a profoundly mystifying version of Taps on Monday morning, 90% of the crowd had headed home and only three cameras covered his set.

A Gift to Eight Million New Yorkers on the Great Lawn

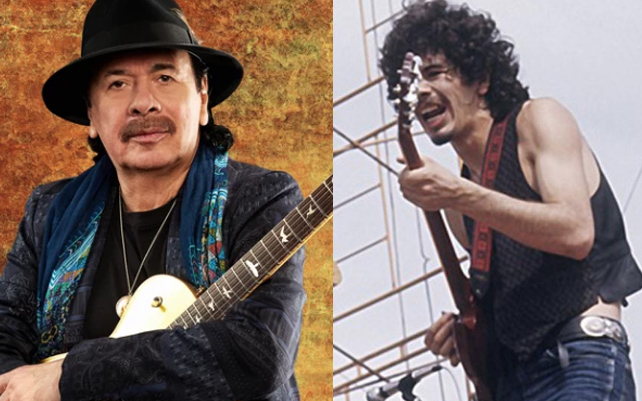

Next Saturday, August 21st in Manhattan will be different. Mayor Bill de Blasio recently announced and trumpeted New York City’s end-of-summer Homecoming Concert as the “concert of a lifetime. Maybe you could compare it to Woodstock.” It’s being co-produced by NYC, Clive Davis and Live Nation. Says Davis: “It will celebrate a spectacular range of musical genres, styles and eras, while including some of the most iconic artists of modern music.” Headliners include Bruce Springsteen, Jennifer Hudson, Paul Simon, Patti Smith, LL Cool J, Barry Manilow, Journey, Elvis Costello, and The New York Philharmonic. Carlos Santana, about to launch his debut album following the ’69 Woodstock fest, will again perform.

60,000 ticketed folks showing proof of vaccination will easily fill Central Park’s Great Lawn—a 55 acre green pasture of bluegrass and ryegrass between 79th and 85th streets. 80% of all tickets are free, with VIP seating peaking at $4,950. (Where else but New York City could you imagine a free concert with VIP seating peaking at $4,950?) The show, starting at 5:00pm, rain or shine, and surely rolling through much or most of Sunday, will be internationally broadcast. Smaller shows with different artists will be held in the Bronx (Monday, 8/16), Staten Island (Tues. 17), Brooklyn (Thurs.19) and Queens (Fri, 20).

Patrons with an extra upfront ticket to the August 21st gala are welcome to contact this newsboy.

Regions: New York