DOC NYC Nov. 9-27

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw highlights America’s largest documentary festival, including four snap-crackle-and-pop volcano docs

No, your reviewer didn’t actually haul a sleeping bag into the IFC Center, Cinepolis Chelsea or the SVA Theatre (16 screens in total). And even if the most fanatic cinephiles had elected all-day, all-night viewing—cinema-crawling from lower 6th Avenue up to West 23rd Street and back, then home-viewing til dawn—they’d have missed some of the 200+ docs and events rolled out for this 13th annual fest. It’s still only a 24-hour day, even in the city that never sleeps. You do the math.

But the business model for DOC NYC, as well as Manhattan’s other prestige festivals, is slowly evolving into a have-it-your-way menu. Both in-person and online viewing were available November 9-17, with extended online screenings on demand across the United States through November 27. Was this a successful formula? An informal survey of publicists’ reports revealed a significant number of the 110 features sold out their in person premieres. On the other hand, many selections quickly went to half price, and there was a $5 flash sale (74% off box office ticket price) on more specialized topic films. An all-access package would have cost you $699, while an online shorts pass (including 34 DOC NYC U student films) was just $49. The five major corporate sponsors of this downtown Manhattan festival were Netflix, A&E IndieFilms, Apple Original Films, NBC News Studios, and Warner Bros. Discovery.

Two distinguished indie filmmakers were presented 2022 Visionaries Lifetime Achievement Awards: Geralyn White Dreyfous founded the Utah Film Center, has produced or exec produced 180 docs (including Won’t You Be My Neighbor? and Freedom on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Freedom), and has taught doc and narrative writing at Harvard. Werner Herzog is the renowned director of narrative classics (Fitzcarraldo, Aguire, the Wrath of God) and two premiering docs, Theater of Thought and The Fire Within. Separate days were devoted to in-depth education on cinematography, editing, music, producing, funding, and journalism.

Other popular returning programs included “40 Under 40,” focusing on young doc creatives; “Documentary New Leaders,” honoring industry vets innovating inclusion and equity programs; the mentoring “DOC NYC x Video Consortium Storytelling Incubator,” pairing debut documentarians with veteran doc makers; the annual “Industry Roundtables” for works-in- progress; and NBC’s “Meet the Press Film Festival,” featuring NBC news correspondents and anchors in conversation following six politically charged docs. More and more, DOC NYC is becoming a training ground for developing skill sets in all facets of documentary creation.

The Volcano Angle

It’s got to be more than coincidence or Lucky 13 choices that four feature length documentaries on volcanoes (dormant and active) were up on big screens in this fest. On November 13, The New York Times devoted its entire Sunday magazine section to our age of destruction and rebuilding. Matthew Thompson, in his lead essay, defines a few of the disasters most of us live with, day after day and season after season: “Plagues, droughts, floods, toxic air and water, wars, massacres, famines, earthquakes, heat waves, recessions, dust storm, despotism—slow-motion nightmares are crushing into fast-moving catastrophes, each one amplifying the next.” Curiously, volcanoes are missing from Thompson’s hit list. Maybe even in Manhattan, with occasional sink holes collapsing streets, gas leaks blowing sewer lids sky high, and water pipes bursting and halting traffic, we feel at a “safe remove” from volcanoes. Most of us aren’t planning to visit one. If it’s not an active menace (or even a latent menace like COVID and its endless variants), maybe it’s easier to watch. Maybe four different volcano docs, viewed sequentially, can become a cinematic revelation. That’s this writer’s takeaway from some serious marathon viewing.

Way before 1990s flicks like Dante’s Peak and The Volcano were seducing us into watching their “Coast Is Toast” cliffhangers, Hollywood had a love affair with volcanos. In 2005, director Martin Scorsese and his nonprofit The Film Foundation—who have an eye for restoration like no one else—tasked UCLA with restoring Republic Pictures’ Fair Wind to Java, a 1953 Saturday matinee thriller. In the movie, Fred MacMurray captains a trading ship in the East Indies in 1883—the same year the legendary Krakatoa volcano blew its stack, killing 36,000 in the loudest explosion ever heard on earth. MacMurray thinks there’s a trunk of 10,000 diamonds stashed in a native temple neatly tucked into the side of Krakatoa, of all places. Republic spent most of its budget on fancy miniatures of Krakatoa erupting in gorgeous Trucolor, chasing away MacMurray and company, unscratched. Marty showed it at the Tribeca Film Festival, then brought it uptown to the Museum of Modern Art and showcased it again four years ago. The perfect kids’ matinee featured a scary volcano that never hurt anyone.

Which brings us to the four featured docs in this 2022 DOC NYC. Fire of Love, already a critic’s choice at New Directors/New Films, migrated downtown for an encore fest showing. The review is linked here for your reading pleasure. Then hold onto your hat as you discover the snap-crackle-and-pop of not one, not two, but three more big screen wonders:

White Night: Tania Ximena Ruiz, Yolloti Alvarado: Mexico: 2021: 82 minutes

In 1982, the Zogue indigenous people of Chiapas Mexico lost their entire village to the Chicano volcano they lived beneath. Many survivors resettled, but some mourned their ancestors and stayed on, rebuilding and tending their cows and chickens while keeping a wary eye on the dormant volcano, which bubbles away as its plumes of steam lightly waft over community fields. White Night, a moody, melancholic ethnographic study, shows what happens when curiosity mixed with a longing for possible buried treasure leads to an excavation of the village, which remains buried under 20 feet of earth.

The treasure being contemplated is the village church bell, which younger villagers estimate might bring up to 200,000 pesos if the bell and chalice turn up intact. Profoundly serious discussions are held on whether an excavation might stir souls, or even awaken the dead as well as the volcano. One middle-age survivor, whose own mother perished during the avalanche of rock and ash minutes after giving birth, wants to reclaim the umbilical cord that was torn away as his mother tried to flee. The men go to work with picks and shovels.

It gives away nothing to reveal that nothing of the church bell is found. A chair, a few intact bowls, a rock on which a victim crudely inscribed the Zoque word for “help” are the best of the sad finds. But what matters in White Light is the stubborn commitment of the Zogues to their land, even as they continue their lives in the shadow of a volcano that will remain a lifelong threat. The native searching for his umbilical cord fashions a raft which carries him out into the volcano’s own sulfur lake (pictured). There he climbs onto a jutting rock, nude, nearly surrounded by volcanic steam, and sits. It’s a steam bath unlike any you’ve ever witnessed. His voice-over narrates his search for the one link with his mother that Chicano wrenched away 40 years ago. He believes he’ll find it somewhere in the volcano’s core.

Beautifully shot and leisurely paced into a captivating 82 minutes, White Light is the first patient, painful story from an indigenous community to emerge from a volcanic devastation.

The Fire Within: Requiem for Katia and Maurice Krafft : Werner Herzog: France, United Kingdom, Germany: 2022: 84 minutes

Our linked review to Sara Dosa’s Fire of Love makes clear that her documentary on the premiere volcanologists was an eternal love story. Dosa’s take is that while the Kraffts were serious scientists dedicated to warning the world away from active volcanoes, they were also traveling performers who couldn’t resist the temptation to get up close and personal with the forces of nature they studied and loved too much.

Herzog has a different point of view, drawn almost entirely from a quarter century of Maurice’s 16mm celluloid footage and Katia’s 400,000 Nikon images. He builds a compelling portrait of the Kraffts not as volcano chasers but as artists–master filmmakers “driven to wrestle images from the claws of the devil” in showing nothing less than the creation and destruction of the world. Herzog believes the Kraffts’s deaths—trapped in a massive pyroclastic flow from Japan’s Mt. Utzen in 1992 that they were much too close to and couldn’t possibly escape—kept them from ever assembling a documentary of solemn grandeur.

So Herzog—who else?—has done it for them, as a requiem with stately music, editing another landmark chapter on the world’s wilds. He’s done this kind of crafting before, weaving together years of summer footage by a naturalist so obsessed with an Alaskan grizzly, he followed the bear over a decade, filming the eight foot tall male up close, once too often. Both Grizzly Man and The Fire Within are gracious, admiring gestures, a bow from one intrepid explorer to others, and when Herzog confesses he wishes he’d been with the Kraffts on their global travels, you know he would have gladly volunteered to carry their equipment.

Herzog, now 80, has always been a scholarly precisionist, the writer/narrator with the stern, penetrating voice that silences any notion you might have of rustling your popcorn. When he lectures in Manhattan, it’s often at The New York Public Library, where he considers himself a citizen of the world. His latest books are a 542-page conversation with Paul Cronin (Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed) and The Twilight World, a novel based on the life of Hiro Onoda, the last surviving member of the Imperial Japanese Army who surrendered on a small Philippines island 29 years after the end of the second world war. (See critic’s choice review on Onoda: 10,000 Days in the Jungle.) Herzog’s own Rogue Film School course defines filmmakers as “thieves who get away with loot from the most beautiful and the most scary and the most spectacular places you can ever find.” For Herzog, the line between fiction and commentary doesn’t exist. “My documentaries are often fiction in disguise,” he says. ”I consider Fitzcarraldo to be my best documentary.” (See critic’s choice review on Carlito Leaves Forever, a 9-minute short on a gay Peruvian youth. Herzog personally supervised the student production, shot in an indigenous jungle community close to where the teacher created Fitzcarraldo in 1982).

A key collaborator on The Fire Within, working with him for the 10th time, is the cellist and music composer Ernst Reijseger. As the Kraffts go in tight on the zones of destruction adjacent to volcanoes in Indonesia, Alaska, Hawaii, and Washington, the score’s arcane instruments and voices counterpoint the silent, stripped devastation of landscape. Reijseger’s sacred score, combined with Herzog’s pitiless commentary plus the Kraffts’ disregard for the slim safety rails they’re holding onto, are close to overwhelming. This is not easy viewing; most communities have been erased, leaving only flattened trees and the occasional skulls and dust-covered remains of livestock and humans where they fell.

Examine the large lead image in this article—Maurice is photographing Katia tentatively exploring an island wiped clean of life in Indonesia in 1983. Seconds later, yet another eruption occurs, chasing the couple back to their canoe and a boat waiting offshore. Yet even with another gaseous dome collapse escalating downhill at 400 mph, spewing steam exceeding 1000 degrees, Maurice keeps shooting. He’s the last to safely board the boat. Many scenes like this echo Herzog’s fascination with fire, which began in 1992 with Kuwaiti oil fields aflame in Lessons of Darkness. But sometimes Herzog pauses to simply admire Katia making her way by horseback or camel through some barren terrain, and Herzog inserts a vocal that for all the world sounds like it was purloined from a Sam Peckinpah western. It’s a welcome break. The director even includes a sequence where the Kraffts stop to watch a native crew pulling up a car that’s fallen into a deep ravine. Anchored by ropes, a community pulls and tugs, matching your indelible memory of the inch-by-inch journey of Klaus Kinski’s 320-ton steamship being pulled up a mountain, by hand, in Fitzcarraldo. This is a grace note, and it comes just in time to let you attend that waiting popcorn.

The Volcano: Rescue from Whakaari: Rory Kennedy: USA: 2022: 98 minutes

Kennedy, an Oscar-nominated documentarian (Last Days in Vietnam), knows something about fire. In 2018, she and her family evacuated their Los Angeles home, which narrowly escaped destruction in the Woolsey Fire. “Our house was saved by two neighbors armed with a bucket and a shovel,” she told Filmmaker’s Lauren Wissot. A year later Kennedy was drawn to the sudden and unexpected eruption of Whakaari/White Island off the coast of New Zealand, trapping 47 visiting tourists, some of whom were taking selfies at the rim moments before it blew apart. It was the last of 1,011 previously unremarkable tourist visits, though Whakarri had experienced eruptions in 2012, 2013 and 2016. This time 22 vacationers and crew would die, some instantly, some on the tourist boat’s 90-minute frantic return to land through choppy seas.

Kennedy spent over a year talking with survivors and local officials who’d agree to share their experience, and another nine months with editor Jawad Metni, selecting the photos, home movies, found footage and 16 minutes of continuous cell phone video and audio. We hear and see survivors stumble through burning steam, black smoke and white ash back to the pier. The director engaged Ron Howard, Brian Grazer and Leonardo DiCaprio as executive producers. One of the industry’s most eminent music composers (Hannibal, Mission: Impossible 2), Hans Zimmer—who Werner Herzog claims started his composing career after watching Fitzcarraldo—was hired as the thriller maestro. If you’re thinking this would make the Netflix home viewing sensation of the holiday season, you can start heating up the popcorn right now.

Some of the visitors were in shorts. Their only protections were hard hats and masks to ward off any irritation from the tranquil steam. The key talking heads—who win your empathy instantly—are a honeymooner couple who the camera gradually reveals are bearing scars over much of their bodies.. “The steam looked like Mars or something. The guide said ‘do not go too near the edge of the crater,’” she tells us, matter-of-factly. You can’t take your eyes off her. Nor the young man who’s endured 17 surgeries as well as the loss of his mother, father and sister, who calmly narrates all this without losing it.

The pulp writer Cornell Woolrich was the master at engineering innocents into situations where they make one fatal mistake. Then, often, whether they live or die becomes a race-against-time. A prime reason so many of Woolrich’s stories and novels have become irresistible templates for successful movies (Rear Window, The Bride Wore Black) are the unimaginable events that ordinary people haphazardly fall into. Kennedy’s exec producers grasped that at once, lending the kind of moviemaking advice and expertise the director and her editor have fashioned into a throat-grabbing chiller.

Of the four volcano documentaries in this DOC NYC, Kennedy’s may be the one you’ll remember longest, not just for its technical superiority, but because hers has the most memorable survivors. Whakaari has been closed to visitors since its catastrophic eruption four years ago. The only eyes on the island today are permanent geo cameras. “I do think,” adds Kennedy, the youngest daughter of the late senator, “the fact that subjects may know I have experienced tragedy in the public arena could create a connection or the hope of a shared understanding—that my own experiences might help others feel safe sharing theirs.”

The Music Corner

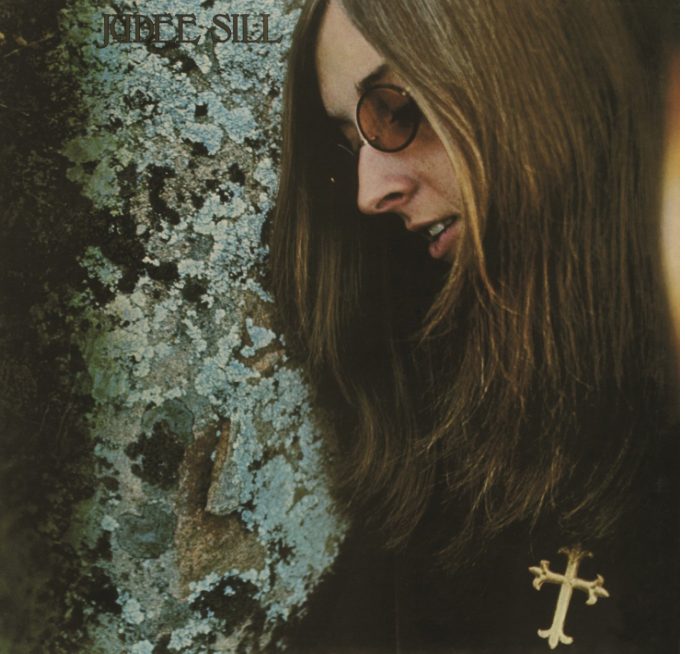

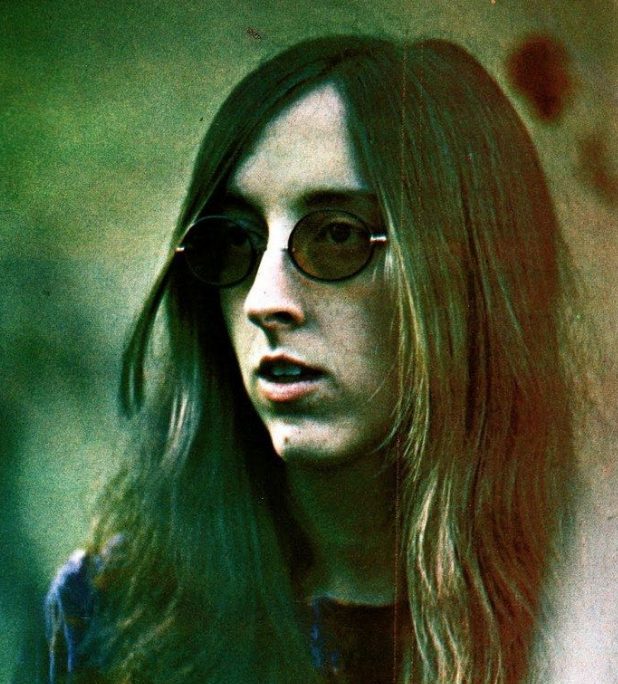

Lost Angel: The Genius of Judee Sill: Andy Brown, Brian Lindstrom: USA: 2022: 92 minutes

David Geffen Hall, formerly Philharmonic Hall / Avery Fisher Hall in Lincoln Center, now bears the name of its $100M donor. Geffen’s generous gift paid a chunk of the badly needed renovation of the home of the NY Philharmonic Orchestra. It’s a remarkable coincidence that once upon a long, long time ago, Geffen signed Judee Sill as the first artist on his Asylum records label, in 1972. Most music and movie people would resist the suggestion that Geffen should lend some support to getting this infinitely worthy doc on Judee’s battered life onto one of Lincoln Center’s three neighboring movie screens on West 65th. But Geffen’s an enthusiastic talking head in Lost Angel, and maybe he could help open her biopic in the shadow of his splendid concert hall. After all, the record entrepreneur did set up the self-taught singer/ songwriter with a platform to fame and fortune that she never, ever achieved. Just a thought.

Here’s another: Lost Angel is a dope doc as important, maybe more important than Laura Poitras’ uncompromised portrait of photographer/activist Nan Goldin, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, which migrated from the New York Film Festival downtown to DOC NYC. Nan’s still out there on the barricades, but Judee left the room, age 35, in 1979. Her early life, raised in Oakland and shaped by abuse, a string of armed robberies of gas stations and liquor stores, multiple bags of heroin every day, sex work and a reformatory stretch, had more than enough bloodshed. But she’d picked up piano, church organ, bass, flute and guitar in confinement. The beauty would start in her music when she arrived in LA, living and composing in a ‘55 Cadillac convertible where her carmates were a couple beatniks and fellow junkies.

Geffen and the hugely successful roster he subsequently signed (David Crosby, Graham Nash, Linda Ronstadt, Jackson Browne, John David Souther) all admiringly describe Sill as the classic outlaw maverick. Ronstadt puts Judee’s writing genius next to Brian Wilson. With songs steeped in spiritual imagery, soul-windows piano and four-part church choral, Asylum probably hoped Sill’s debut might be an alternative take on hit albums of the day like The Who’s “Tommy” or at least smaller religious pilgrimages like Spooky Tooth’s “Ceremony” and The Pretty Things’s “Parachute.”

Jesus-rock was an up-and-coming category in record stores following the Woodstock fest, and this writer (then creative director at RCA Records) regrets that Geffen signed Sill first. Her debut LP contains her first single, produced by Nash, “Jesus Was A Cross Maker,” which was inspired by her love affair and breakup with Souther, like so: “Blindin’ me, he keeps remindin’ me, he’s a bandit and a heart breaker, Oh but Jesus was a cross maker.” (Ronstadt later covered it using “Bandit and a heartbreaker” as her title, leaving out any reference to Jesus or crosses. it made the charts.) Geffen gave Judee her own billboard on Sunset Boulevard—one of the music industry’s most desired totems of the era—and his advance took her from living in the backseat of a convertible to a home in the Hollywood hills with a pool. You can see where this is heading.

Like so many music artists then (as now), Geffen toured Sill opening for major headliners—Crosby and Nash, the Youngbloods, the Association, Edgar Winter. She hated it. How many artists enjoy playing to an audience that comes to see a headliner and totally ignores the opener? (The most recent example, here in uber-sophisticated New York, was a brilliant instrumentalist with a small but dedicated fan base, who opened in a venue in which all the lights were deliberately left on so patrons could booze up and chat before the headliner.) When Sill’s first two albums didn’t garner the airplay, reviews, or even a fraction of the sales of Asylum’s other hit sellers, the label cut her loose.

Directors Brown and Lindstrom lovingly detail nearly every important song Sill recorded, including a few in her third and last album in 1974, which stayed unreleased until 2005. There’s ample footage of her performing to small, receptive audiences in public parks and clubs in the US, England and Mexico. Lyrical animation works its way through her diaries and jottings. Judee carefully notes her choices of drugs and synthetic opioids—peyote, marijuana, heroin, opium, demerol, morphine, codeine phosphate, speedballs—along with lyrical themes she was exploring. “However you are, is okay” became her m.o. Along the way, there were car accidents, and an overdose of codeine and cocaine took her out. Beauty and bloodshed in the 1970s. It ain’t gone away.

Lost Angel also bears a resemblance of sorts to another recent critic’s choice music doc, Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, A Song. In that biopic, the aging poet and songwriter, stung by financial betrayals which rendered him nearly penniless, returned out of necessity to touring at age 80. To his amazement and eventual pleasure, audiences discovered “Hallelujah,” an endless hymn from his first album (that Columbia refused to release), which became the signature chant of his revival, his concert hall resurrection and probably his legacy. Hallelujah, indeed. Judee Sill won’t be around to see if “Jesus Was A Cross Maker” might have done the same for her career. The New York Times gave Sill one of its Overlooked obituaries in January, 2020. And If Lost Angel ever finds the audience it richly deserves, only time will tell.

Dream That I Had: Evelyn Lee: USA: 2022: 4 minutes

The publicity description for this animated short is deliberately obscure: “A Grammy award-winning music producer talks about his life and history.” But he’s not named. The only animated image provided shows a faceless band of rockers. Apart from the director, no credits are provided upfront or anywhere in the short. The producer who voiceovers the narrative of his youth and post-adult years never identifies himself. We have a mystery so tantalizing it can’t possibly be some lunatic willing a teeny tiny short to extinction in indie hell forever. We watch and listen for clues.

He fell into the music scene watching Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert in the 1970s, on a small, black-and-white Panasonic television set, laying the fretboard of his first guitar across the screen to keep up. As a young teenager in Manhattan in 1980, he began inserting himself into older bands, declaring he could play faster than anyone in the band. As a speed guitarist before there were speed guitarists, he played six nights a week all over town–CBs, A7, The Mudd Club, the Peppermint Lounge. With his first four-track cassette rented from Sam Ash, he began recording and overdubbing himself and others.

Evelyn Lee’s frantic animation is matching his every considered word with precise, vigorous, fully detailed black-and-white drawings that tear up the screen. Who the hell is this guy? Then he drops a mention of Barkmarket–oops, that rings a distant bell. And that he produced an album for Helmet–hold on, louder bell. At this point, the cat’s out of the Google bag: it’s Dave Sardy. And with a minute remaining, he’ll close with a summation that after eight years of playing back and forth, and producing back and forth, and doing neither to his full satisfaction, he decided he’d do better just producing.

What he doesn’t mention is that his career with Barkmarket spanned the late 80s to late 90s, in which singer/songwriter/guitarist Sardy produced, recorded and mixed all their noise rock albums. Or that he’s received three Grammy Awards for his work with OK GO, Wolfmother and Marilyn Manson. Or that he’s contributed to a long shelf of big movies including Spider-Man and Spider-Man 2. Or that, according to one veteran indie musician who’s a deep Sardy fan, he also mixed ZZ Tops’ 2012 La Futura album. Ms. Lee has an MFA from the U of California in Experimental Animation, and has poured her heart into mile-a-minute drawings that are the visual equivalent of speed guitar. Whew. And you thought Lou Reed and Nick Cave were the phantoms of rock. Sometimes a four-minute carve-out cut can surprise you more than a whole 60-minute album. You heard it only in The Independent.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the New York Jewish Film Festival, January 11-24, 2023.

Regions: New York City