New Directors New Films March 29-April 9

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw uncovers a mood of menace in top dramas from Tunisia, Portugal, Chile and Thailand

Late Friday afternoon March 13, 2020, Bill Wolf, the preeminent 94-year-old senior critic of the New Directors/New Films press corp, and this writer scurried out of the Museum of Modern Art on West 53rd St. We’d just finished watching Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, a gorgeous 150-minute Chinese epic, the last film of the first of two scheduled weeks of press screenings. MoMA seemed anxious to hurry people out because they were closing early. Something to do with that COVID bug.

Bill and your critic wished each other a pleasant weekend, confident we’d resume the second week of screenings Monday. Two weeks later Bill was dead from COVID-19. He was among the first wave of 45,000 New Yorkers to have perished from the silent killer. Nine months later, Film at Lincoln Center’s Virtual Cinema restarted the festival… though Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains had somehow slipped away in the mists of time. Your reviewer spent more than one solid year sheltering-in-place, going nowhere, ordering in groceries, listening to vinyl LPs, reading, and watching old movies on VHS and new movies via festival links.

This March we’re viewing the 52nd edition of ND/NF, and once again it’s entirely in person with FLC and MoMA curating and hosting. The simultaneous online viewing options of prior festivals around town have taken a slow fade to black. Manhattan indie cinemas still recommend masking and a number of theatrical productions now offer performances for masked-up audiences. It’s hard not to feel something in the mood of a-night-out-on-the-town has shifted. Cinephiles are still looking for the next Chantal Akerman or Spike Lee, the new director with the aesthetic reach of a Wong Kar-wai or Ryusuke Hamaguchi. But this festival in part reflects a cautionary tonality that’s settled more strongly in independent cinema worldwide in this century, even before COVID darkened theaters.

One early example was Lucrecia Martel’s The Headless Woman, in which a socialite of privilege driving a rural road hits something—a box? an animal? a person?—leaving behind an indecipherable lump stretched out in the dust. Another was Neighboring Sounds, Kleber Mendonça Filho’s debut film, set in an old style Brazilian neighborhood feeling the impact of new style urban density. Its idea of menace is a hand scraping a metal key across the trunk lid of a new Audi AG. Or consider a sinkhole: We see small ones now and then in Manhattan—but they’re not yet the size of an entire plain near the Dead Sea in Israel, in Nimrod Eldar’s first brooding feature, The Day After I’m Gone.

Indie movie menace sneaks up on us everywhere, even in a soybean field in Madiano Marcheti’s Madalena, where a trans worker is missing near an oasis containing a lush lagoon that may be concealing a killer. Or indoors, as in Marco Dutra and Juliana Rojas’s Good Manners, set in a luxury high rise in São Paulo, where a delicate music box is delivered to a pregnant lady of leisure whose belly seems to be growing a werewolf. Menace isn’t always movie terrorism or a prelude to horror or even film noir, but like all three it conveys a sense of lurking dread.

Maybe it’s more than just the growing presence in Manhattan of speeding ebikes, hundreds of illegal weed shops, Urgent Care and City MD storefronts, along with the profusion of disease testing tents lining city sidewalks, that rattle our confidence in returning to normal. A lot of movies worth remembering these days seem fixed on toying with our nerves, too. Four of this ND/NF’s most absorbing features draw their menacing settings from the past and present. One is set in a hollowed-out neighborhood of empty, unoccupied apartment complexes in Tunis, built for a failed regime over a decade ago. Another takes place in a rural village in 1970s Angola, beset by a brute force military its native citizens can only protest by rising from the dead. A third finds an upper middle class woman drawn to help an injured youth during the ultra-repressive Pinochet regime in Chile. And in the one uneasy contemporary drama, set in a contemporary high school in Thailand, students are threatened by an autocratic administration chipping away at diversity, equity and inclusion—qualities we’re seeing being eroded by the minute right here in America.

G.K. Chesterton, the distinguished British author, could have been referencing motion pictures as well as books when he noted that “literature representing our life as dangerous and startling, is truer than literature that represents it as dubious and languid.” Each of these four ND/NF critic’s choices is admirably dangerous and startling:

Ashkal- The Tunisian Investigation: Youssef Chebbi: 2022: Tunisia/France/Qatar: 94 minutes

The camera stares at empty, unbuilt shells of high rises. The opening titles tell us they were “built for dignitaries of an old regime, to be part of a modern, rich city….then an immolation set off a Tunisian revolution… the regime toppled, construction ceased…today construction is resuming, little by little.”

Wait a minute: “Immolation”? What immolation? There’s a factual backstory director Chebbi won’t tip us to, that’s worth knowing upfront. In 2010 a fruit and vegetable vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, was arrested by the police for selling without permit in downtown Tunis. His cousin says the police continually harassed Bouazizi, demanding bribes. His scales were confiscated. Angry and desperate, the vendor went to the government building to complain. When no one would see him, he set himself on fire. It was captured on video. A taxi driver beat down the flames, but Bouazizi never awakened from his burns. This set off weeks of protest known as the Arab Spring, which ended the reign of President Ben Ali.

Director Chebbi spins off fact into a terrifying fantasy premise: What if the vendor hadn’t died? What if he returned to exact revenge, living in the massive construction shells of his hated past government? The mystery of multiple charred corpses is what two police detectives, Fatma (Fatma Oussaifi) and Batal (Mohamed Grayaâ) are trying to solve together through this truly hair-raising chiller. Batal’s a devout, experienced officer with a family, Fatma’s the bright, intuitive daughter of the police commissioner. A night watchman, a young woman, a police officer, a passing motorist are all dying sequentially, by self-immolation. They end up “ashkals,” which is Arabic for shapes.

One consistent clue is that each victim carried a device containing the video of that vendor’s burning. Another is that none of the victims appear to have struggled or tried to escape against the flames that engulfed them. Like the smart detective she is, Fatma begins to theorize each victim might conceivably have willed his/her own suicide. But why? How? Your mind may be racing along with hers, and it may flash back to the 1950s novel by Jack Finney, a paperback original published by Dell which became the all-time classic horror fantasy by Don Siegel (and its equally creepy 70s remake by Philip Kaufman), Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Doubles. Replicant drones. Oh my God, maybe these are Tunisian Pod People.

At this point director Chebbi starts turning the screws tighter, aided by starkly svelte night cinematography and a music score that’ll vibrate your back molar fillings. The point-of-view switches to that of a hooded figure who sleeps on a lone cot high up in a blackened skyscraper, prays daily five feet behind the detective, buys his eggs from a hole-in-the-wall vendor, feeds scraps to stray dogs, and is patiently stalking his two pursuers. We glimpse he wears a molded mask with different size eye holes. And we want to warn detective Fatma that—as wise and dedicated as she is—she’s playing with fire gazing into that video footage.

Lots more surprises await you. Ashkal has already won the 54th FESPACO African festival’s Stallion of Yennenga award (out of 170 entries) for best fictional or documentary feature. The ceremony was held in Burkina Faso in West Africa, and the honored director has said his sophomore film “borrows things from Tunisian reality but looks at them from another point of view.” It sure does that. Ashkal is 2023’s scariest festival selection to invade Manhattan.

Tommy Guns: Carlos Conceição: 2022: Portugal/France/Angola: 119 minutes

If Ashkal is the scariest new movie in town, Tommy Guns is surely the most relentlessly distressing. It will stand as perhaps the most disturbing international drama of menace since Claire Denis’s White Material 13 years ago. Denis lived in Burkina Faso and knows the history of post-colonial French and African relations as well as any filmmaker alive. She carved out her tale of escalating dread of a coffee plantation owner (Isabelle Huppert) obsessed with harvesting her crop, even as her family and staff are systematically slaughtered. White Material was widely seen because it was anchored by Huppert, the screen’s most formidable expert on crazed suffering.

Carlos Conceição’s Tommy Guns, which has been mistitled from its original Nação Valente (Glorious Nation), has created an equally frightening panorama of the last days of rural warfare in Angola in 1974, pitting an indigenous people in huts against a trigger-happy battalion of clueless but lethal Portuguese soldiers. Conceição is nearly as assured and as technically proficient a director as Denis, and Tommy Guns is often as riveting as White Material. Both are dramas you watch with your fingers poised to cover your eyes.

One example finds a young Tchissola (Ulé Baldé, pictured), speaking only the Nyaneka language, trusting fate as she makes love on the ground with a handsome young white recruit, who promptly murders her. His commanding colonel (Gustavo Sumpta, simmering and bellowing) is an unstable racist who orders the camp’s unhappy Black cook to be gone and then hunts him down like pray. We also witness Portuguese soldiers falling to Angolan snipers. Both the native settlers and their occupying force appear trapped together by a wall twelve feet high that looks like it extends clear to Mexico.

Occasionally Conceição pauses the open warfare and inserts a scene that’s meant to restore some sense of normalcy, but instead plays as weirdly unsettling. A convoy of men set out under moonlight to rescue a huge abandoned framed painting of French actress Brigitte Bardot, inexplicably left beside a river, which they dutifully store away. Later they’re treated to a performance by an imported dancer/sex worker, Apolónia (Anabela Moreira, gamely giving all she’s got), who works up a five-star strip to Vangelis and Aphrodite’s Child’s grinding 70s anthem, “Spring Summer Winter Fall.” And just when you think Tommy Guns has tapped out its bizarre surprises, buried hands shoot up from cemetery soil and a village of the undead rises to totter toward their open-mouthed oppressors (pictured). Yup, Conceição tosses in a little magic realism mixed with Jacques Tourneur’s 1943 I Walked With A Zombie. This has the odd effect, curiously, of leavening a very jittery mood. All in all, Tommy Guns illustrates how grim history lessons, no matter how obscure, possess the power to jar and jolt a viewer’s conscience.

Chile ‘76: Manuela Martelli: 2022: Chile/Argentina/Qatar: 95 minutes

Sense a pattern developing in the ND/NF films being championed? No matter the country or era, bad administrations do terrible things to good people. Martelli has taken to heart one of the wisest decisions a first feature director can make: Examine a small period in your homeland’s perilous past. Write your story entirely through its impact on one woman. Then cast a screen/television/theater veteran at the top of her game—here Aline Küppenheim as Carmen—who you trust will hold the viewer’s rapt attention and interest through 95 increasingly urgent minutes. Surround her with a company who’ll support her every mood, line and gesture. Chile ‘76 is such a win-win for actress, viewer and director, It ought to earn a chapter in every international film school textbook.

Martelli wastes no time setting a mood of menace in Chilean dictator Pinochat’s third year of a 17-year reign of aggressive repression. Carmen’s in an art supplies shop, having paints mixed to touch up her family’s oceanside summer villa, when a pedestrian outside is snatched away screaming. The store protectively lowers its steel shutters from the inside. It’s the third time in a week it’s happened. Carmen’s an idealized socialite of her era—the model mother to adorable daughters, the good wife to a hospital services director busy in Santiago, a woman who gently manages a home staff and is totally comfortable within the secure trappings of wealth.

We observe she smokes too much, takes a whiskey when offered, uses pills to help her sleep. The 70s, you know. She dresses fashionably but conservatively, reads to the blind, donates last year’s look to the poor, runs home movies of her girls growing up. She wears a faint look of weary resignation she carefully masks. We learn she never became the doctor she yearned to be, but she did a stint with the Red Cross. So it’s not surprising when a resistance youth, Elías (Nicholás Sepúlveda) is shot in the leg and sheltered by the family pastor, Father Sánchez (Hugo Medina) Carmen volunteers to care for his wound at her villa. It hasn’t fully dawned on her there’s a growing rebellion swirling around her and people are disappearing.

Elías is the one person who speeds up Carmen’s learning curve. She learns that as a resistance movement member Chile’s administration has vowed to squelch, he’s on Pinochet’s death list. That if he’s captured they’ll torture him to get the priest’s name first. Ever a curious optimist, Carmen asks what he’ll do if the resistance wins out. The personable young man smiles: “We’ll name a hospital after you.” He probably means it. But as the bodies pile up around town, drawing nearer to her privileged enclave, it all feels unlikely. Carmen appears unwilling or unable to connect the dots of a culture falling apart just outside her monied world and her door. She’s trapped in a cocooned, private agenda of children’s birthday parties and seaside windows that are polished to a high gleam, complementing those living room walls that Carmen’s had custom-blended to her perfect shades of orange and blue.

This is, as they say, a tour-de-force for Ms. Küppenheim, an actress who’s mastered the crafts of listening intently to others and often acting entirely with her eyes. You can read worlds in the tiniest shifts of her gaze, and director Martelli believes you will. Chile ‘76 is the quietest, most stealth movie menace of many a festival.

Arnold is a Model Student: Sorayos Prapapan: 2022: Thailand/Singapore/ France/Netherlands: 85 minutes

Diversity, equity and inclusion are sorely lacking in Arnold’s senior year in a Bangkok high school. You could almost say Bangkok’s elementary and secondary education “is where woke goes to die,” just as a U.S. governor is predicting as he begins to maul his state’s school system. But according to this contemporary study of menace in the classroom, woke had no way of existing in Thailand until 2020.

Writer/director Prapapan’s curious, barbed satire opens with the headmaster (Virot Ali) parking his Mercedes in its reserved faculty spot and greeting his first parent visitor of the day, who brings him a present. She’s a helicopter mom fretting about her younger son getting into the posh co-ed school, even with an off-the-books peak at the exam questions. “What other special favors could you offer,” she asks plaintively. “That will depend on what the school gets in return from you,” smiles the Headmaster. Oh boy.

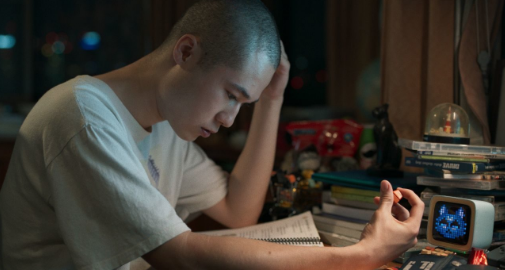

The first day at Sewassee High finds everyone masked-up, with 12th grader Arnold (Korndanai Marc Dautzenberg) returning from 15 months in an American exchange program that COVID shut down. Arnold’s just won a Gold Medal in math in the International Academics Olympiads, so the administration’s already planning to enlist him to shill for Sewassee. The head of one of their academic partners, a “cram school” for students applying to Sewassee, offers Arnold a scholarship in exchange for doing a video extolling the school’s virtues. “You’re paying me to lie?” asks the bemused youth, though he accepts the bulging envelope of cash he’s handed as a sort of retainer. What Arnold, the not-so-model student, is really conflicted about is his dad, a French ex-pat and a performing satirist, who’s been arrested and deported by Thailand’s government. The boy is thinking he’s returned to the original high school from hell, with its 1,001 constricting rules (no long hair, no dyed hair, no questioning authority, obey all school commands at all times) and instructors who throw chalk at you if you doze off in their nationalist lectures.

There’s no overt menace in this oddly staged series of vignette scenes that may or may not have been deliberately assembled to look and feel like a by-the-book TV docudrama. The script, acting, editing and continuity often feel wooden. What holds you—and what obviously impressed the Hubert Bals fund, one of the world’s most revered backers of first class indie film drama—is its truth-is-stranger-than-fiction overview of education.

It was inspired by Thailand’s 2020 “Bad Student” Movement and its guide to surviving school, written by students. Prapapan shrewdly pinpoints how both girls and boys are diminished and subjugated by Sewassee’s draconian rules and regulations. A state propaganda film, “How to Live Elegantly Like A Thai” is required classroom viewing. In case you don’t believe boys are still caned in Thai classrooms by their teachers (here a nasty teacher supervisor acted by Niramon Busapavanich), Prapapan intercuts actual cell footage of canings in real life classrooms. The blows to boys’ buttocks are much more severe than in his dramatized scenes.

At this point the director replaces satire with action, illustrating how high school girls organized and fomented a continuing rebellion, both in reel and real life. Arnold’s the kid caught in the middle, torn between leaving an academic system he deplores, and accepting a big money offer to become a “signaler” who attends exams and lets select students (whose parents have paid a pretty penny) copy his answers. The moral issue is whether Arnold has it in him to try becoming an honest student.

Much of this portrait of a damaged and decaying ed system in an international community is also eerily similar to the recent scandals on American college campuses and corrupted admissions systems. It’s a seething, uneasy menace-on-the-move, lapping right up on American shores. Prapapan’s considerable gift as a filmmaker is reminding any viewer who thinks something this awful couldn’t happen in the USA, that it already has.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks at the 22nd annual Tribeca festival, June 7-18.

Regions: New York City