Tribeca Festival June 7-18

A 22-year-old fest with no “film” in its name still rolls out 109 dramas and docs plus 76 shorts

The surest sign that big screen movies are alive and well in New York City came from festival co-founders Jane Rosenthal and Robert De Niro, paying tribute to significant past events and films. Tribeca’s Opening Night documentary, Kiss the Future, was the North American premiere of a journey following a community of musicians and artists through the siege of Sarajevo during the Bosnian War in 1992. The festival’s Closing Night presentation was a 30th anniversary screening of A Bronx Tale, which De Niro directed and co-starred in with Chazz Palminteri, who also wrote the script. “I’m thrilled to see the new restored 4k version,” said Palminteri. Added Rosenthal, who’s CEO of Tribeca Enterprises, “It was an honor to produce Bob’s directorial debut,” reminding us of a partnership that’s continued unbroken in the city both call home. The pair also collaborated on Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman, as well as The Good Shepherd, with De Niro again directing and starring in the latter, and Rosenthal producing both.

What’s changed in recent years is Tribeca Enterprises, which is now a multi-platform media and entertainment company. James Murdoch of Madison Square Garden’s Lupa Systems bought a controlling interest three years ago. He’s obviously a cooperative overseer, as Tribeca’s creative menu has widened beyond film to include immersive, games, talks, TV, music, audio storytelling and comedy. Premieres, exhibitions, conversations and live performances are its borough-wide territories.

Storytelling doesn’t just take place in downtown movie theaters. Tribeca’s wherever you are or want to be, beyond the NYC metropolitan area. If you wanted to bail out for a night, you could have grabbed a ferry boat out to Governors Island and watched Tribeca movies under the stars. Within the city, Harlem’s Apollo Theater hosted the premiere of the horror-comedy The Blackening. Carlos Santana rocked the Beacon on the Upper West Side after Rudy Valdez’s doc, Carlos, as did Cyndi Lauper after Alison Ellwood’s biopic Let the Canary Sing. And in midtown, Japan Society joined up with the fest’s Escape From Tribeca and presented a 55th anniversary screening of Destroy All Monsters, featuring your old pals Godzilla, Mothra, and Rodan.

Program highlights included Tribeca’s Expressions of Black Freedom program, which highlighted films by Misty Copeland and Gloria Gaynor, plus a conversation between Billy Porter and Idina Menzel. Other dialogues with notables included Paul McCartney and Conan O’Brien, David Fincher and Stephen Soderbergh, and Lin-Manuel Miranda with Rosie Perez. The third annual Harry Belafonte Voices for Social Justice award was presented to Oscar winner and activist Jane Fonda. Tribeca premiered a dozen podcasts (spotlighting “The Unmarked Graveyard,” a documentary series about the anonymous dead of Hart Island cemetery in New York), hailed by Cara Cusumano, Tribeca’s director of programming, as “the next frontier of interesting, creative, independent storytelling.” Another premiere in the Audible Original series starred Jessica Chastain in the audio-only The Space Within. In addition, brand storytelling, now an accepted part of the creative menu, is a new way for marketers to trade assets with filmmakers.

Audience film awards went to the narrative drama The Perfect Find and the documentary Rise: The Siya Kolisi Story, about the first Black captain of the South Africa National Rugby Union Team. Select features and shorts are available via TribecaAtHome.com through July 2, a sure sign Tribeca is recognizing the demanding realities of streaming.

Here are this critic’s choices in documentaries, dramas and shorts.

Kim’s Video; David Redmon, Ashley Sabin; United States; 2023; 88 minutes

Back in the late 20th century when Manhattanites owned VCRs along with turntables, portable typewriters, and rotary phones, the place to rent impossible-to-find movies was Kim’s Video. Launched in 1979 by an enterprising South Korean immigrant, Yongman Kim, its seven outlets in Greenwich Village offered movies from 44 countries and boasted a membership of 250,000. (Ethan and Joel Cohen ran up late fees of $600.) Kim’s flagship store on St. Marks Place was home to 55,000 titles, most often VHS bootlegs of varying quality copied off 35mm, 16mm, and 8mm prints, satellite transmissions, and God knows where else.

While Kim’s shelves and spinner racks held their share of edgy experimental, sexploitation and sleaze items, they gave pride-of-place to world class names like Jean-Luc Godard, Agnès Varda, Maya Deren and Robert Bresson. Who else carried Werner Herzog’s Ballad of a Little Soldier? Not Tower or Blockbuster. The staff (Eric, Ryan, Lorry, Sean, Isabelle, all seen here) could be testy or helpful, depending on what you were dying to see. Clerks had their favorite directors, like Michelangelo Antonioni. You could find early Rock Hudson starters like Iron Man and The Scarlet Angel. New York attitude seethed at Kim’s. It became one of the city’s preeminent “underground” bricks-and-mortar retailers. When the FBI raided Kim’s in 2003 and hauled away countless pirated titles in garbage bags, a backroom lab simply ran off more copies.

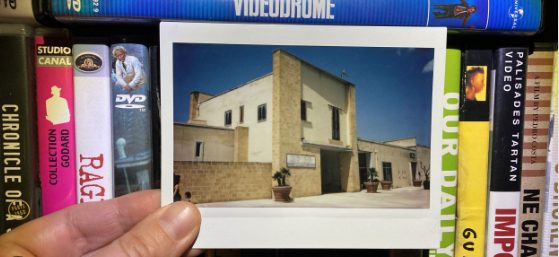

It couldn’t last forever. Worldwide piracy concerns, gentrification, skyrocketing rents, American studios dropping VHS in 2006, plus the coming of DVDs and streaming all doomed Mr. Kim’s VHS paradise. So he posted a Public Notice offering the entire collection, free, to any institution, college or university with 3,000 square feet, that would preserve it and keep making it available to see. The New School, NYU and Wesleyan had interest, but the one application of 40 that won Mr. Kim’s heart came from Salemi, a tiny village in Sicily (only 4,800 miles from downtown Manhattan) which proposed to create an arts colony (with sleeping quarters) around Kim’s mountain of ancient movies. As director (and one-time Kim’s clerk) Alex Ross Perry comments in disbelief, “how could anyone think for a second that sending this entire thing to another country” would ever work?

It didn’t. David Redmon and Ashley Sabin’s affectionate, truth-is-stranger-than-fiction documentary shows you what happened. It’s a lost-and-found shaggy dog tale with the kind of deliriously happy ending that, well, could happen only in the movies. The filmmakers travel from NYC back and forth to sleepy Salemi, starting in 2017. They discover the collection, locked away and molding away in a leaky building, surrounded by a cast of characters who wouldn’t look out of place in Mario Monicelli’s Big Deal on Madonna Street. The chief of police, the former mayor, the present mayor, plus a shadowy figure who may have Mafia connections, all speak highly of Kim’s Video collection and its estimable value to their community. Except the local head of tourism has barely heard of its existence. Redmon, who narrates us through an amusing series of interviews with one uncooperative and untrustworthy talking head after another, is as appalled as Perry was, just thinking about the fate of the collection. Clearly Mr. Kim picked a doubtful guardian for his 55,000 movies. The former proprietor himself travels to Salemi, inspects the dusty facility and damage, and, crestfallen, agrees. The issue then becomes: Is there a remedy?

Redmon, who once worked as a video clerk at Walmart’s before he moved to the East Village and fell in love with movies forever, has a Big Idea. It’s inspired by the dozens of snippets from international cinema (like La Dolce Vita and Nights of Cabiria) he and Sabin have been sliding in as sly commentary. Redmon now says he feels the movies “talking to me,” and what they’re whispering is, “steal us and get us back to New York City.” Drawing on seminal crime classics – The Bicycle Thief, Rififi, Thieves’ Highway, Argo—as cinematic guideposts, Redmon convinces Salemi’s mayor to let them stage and shoot a heist movie, in the middle of the night, in the building holding the collection. Except this becomes a true documentary, with a gang of helpers wearing face masks of Godard, Herzog, Varda and Hitchcock, loading tens of thousands of videos into cartons and onto an 18-wheeler, and hauling them away. For real. Really. You may rub your amazed eyes more than once. The filmmakers actually steal away a major portion of Kim’s stolen collection!

So where do the 55,000 movies end up? Several years of negotiations later, and following the return of the remaining tapes to American shores, there’s Alamo Drafthouse Cinema’s CEO, Tim League, celebrating the grand reopening of Kim’s Underground at Alamo’s downtown Manhattan cinema, just a stroll from the New York Stock Exchange, alongside a smiling Mr. Kim. The movies are rented free to Alamo patrons, and since a lot of Manhattanites no longer have their VCR or even a DVD player, Alamo will gladly rent you one of theirs for a fee. This must be their, ahem, profit point. One can imagine they’ll be selling legal copies of Redmon and Sabin’s smashing doc in no time.

The important legacy here is that Kim’s Video joins other distinguished filmic histories of iconic New York people and places–Bill Cunningham in New York, Burning Down the House (on CBGBs), Joe Papp in Five Acts, Other Music (the music store), Squeezebox (the LGBT rocker bar). We take a deep breath walking into these docs, crossing our fingers that the filmmakers will get ‘em right. Kim’s Video is top shelf—in its gritty giddy way, surely the granddaddy capstone of this downtown Manhattan festival.

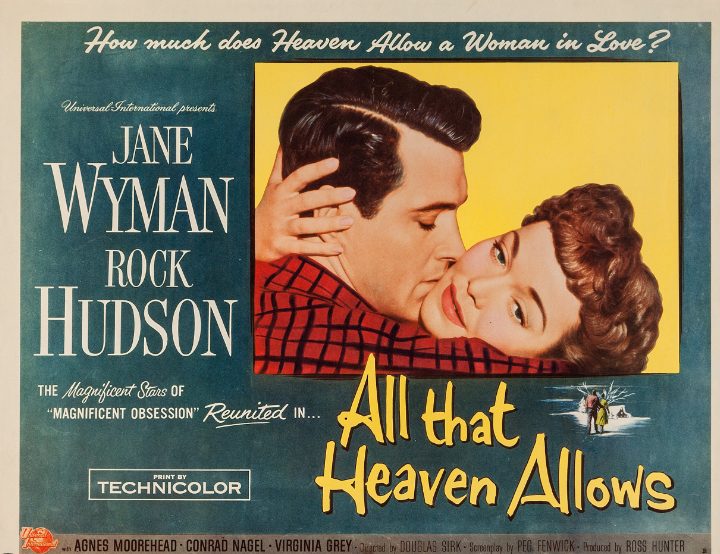

Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed; Stephen Kijak; United States/United Kingdom/New Zealand; 2023; 105 minutes

When World War II ended and families were reunited at the movies, Hollywood decided audiences needed a new hero: The All-American small town boy, writ large. How large?How’s ‘Roy Sherer, Jr.’, 6’5”, 215 pounds, size 14 loafer, from Winnetka, Illinois? This writer’s coming-of-age in the dark in Indiana and Wisconsin movie theaters was spent with Rock Hudson, mostly during the renamed actor’s 15+ years at LA’s Universal-International studios. Let’s see, he was husky Jeff Chandler’s boxing pal in Iron Man, lanky Jimmy Stewart’s riding pal in Bend of the River, pretty Piper Laurie’s boyfriend in Has Anybody Seen My Gal and The Golden Blade, sultry Yvonne De Carlo’s high seas mate in Scarlet Angels, Oh, those up-and-coming roles in blazing Color By Technicolor, in postage-stamp l.33-to-1 aspect ratio, went on and on.

But unlike other handsome hunks at Universal-International—Troy Donahue, Ty Hardin, Race Gentry—this newcomer grew into a leading man who could actually act. Yes, even in his war paint breakout western (released in 3-D) as Taza, Son of Cochise. Then he pursued the ideal girl every 50s college boy dreamed of marrying, Doris Day, in Pillow Talk, Lover Come Back and Send Me No Flowers. Romanced every college girl’s ideal mom, Jane Wyman, in Magnificent Obsession and All That Heaven Allows. At 30 Rock married his agent’s secretary, a perfectly chosen tinseltown working girl.

His career got serious playing a World War I lieutenant in love with nurse Jennifer Jones in Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, and a WWII bomber pilot turned minister, who re-ups at the start of the Korean War, in Battle Hymn,. Followed by his role as a U.S. nuclear submarine captain in the Cineerama spectacle, Ice Station Zebra, (proudly premiered at the Cinerama dome in LA). He held the screen as a jungle doc in 1930s Java in The Spiral Road, playing against scene stealers Gene Rowlands and Burl Ives. He registered alongside Dorothy Malone against louder scene stealers Robert Stack and Lauren Bacall in Sirk’s woozy boozy Written on the Wind. Then he was a journalist pursuing 1930s barnstorming pilots in William Faulkner’s The Tarnished Angels (which Faulkner called the best filming of all his novels). Next as the victim of a nightmare surgeon’s knife that turns him into a younger version of a Scarsdale banker (played by the great John Randolph), in John Frankenheimer’s super-surreal Seconds. Finally, Hudson earned an Oscar nomination as Best Actor playing a Texas rancher who marries Elizabeth Taylor in George Stevens’ Giant, based on Edna Ferber’s best selling novel. This was in a post-war era when newly married couples sat up nights reading immensely popular novels by Hemingway and Ferber and Faulkner and then went out to see their movies.

In all these years watching Hudson grow and mature on the big screen, the last thing any Hudson fan (starting with this writer) outside of Rock’s tightly woven Los Angeles enclave would have suspected was that he was gay. “Rock Hudson is what’s-that-word, ‘homosexual?’” would have been as preposterous as imagining John Wayne might be gay. But Roy Sherer, Jr., spent his entire life playing Rock Hudson who was always playing men attracted only to women. Stephen Kijak’s All That Heaven Allowed is as endearing, heraldic, endlessly researched, carefully assembled, and perfectly titled a biopic as any viewer, gay or straight, could wish for. It’s the penultimate showbiz tale of how Hollywood closed ranks to protect its own at mid-century.

In real (not reel) life, Rock Hudson was discovered and groomed by a gay talent agent (Henry Willson), and ushered into stardom by Universal’s big bucks glam producer (also closeted) Ross Hunter. While legendary director Douglas Sirk, shown in rare clips, is candid about sensing that Hudson was born to the diamond-center stardom the actor predicted he’d achieve, Hunter and Willson were the true teachers of his heterosexuality. More than anyone, they helped Hudson avoid being trampled or even tainted by the Hollywood community’s scandal magazines, which steadfastly refused to play nice. (Confidential, the boldest of the breed, hinted at Hudson’s sexuality, but the one lesbian actress whose film career it destroyed was Paramount’s Lizabeth Scott, who, like Hudson, had been ”covered” and protected by that studio’s major producer, Hal Wallis.)

Kijak has assembled an A-list of past and present voice-over commentators—Sirk and director Allison Anders, actors Day and Laurie, Kathleen Hughes and Howard McGillan. Author Armistad Maupin gave Hudson invaluable advice regarding the closet door the actor chose to close on himself as the price of fame. There’s a gallery of his lovers offering moving testimony to the actor’s tireless work ethic, which inevitably conflicted with his pursuit of a private life. And Kijak’s directorial prowess is never keener than in his choice of film clips—some semiotic signals that gay viewers might pick up on (“I can’t marry you, for a moment I’d forgotten what I am”), others like his fatal realization in Seconds of “the years I spent trying to get all the things I was told were important.”

Hudson’s transition to television is well represented via the McMillan and Wife series during the 1970s, and his ongoing role opposite Linda Evans in Dynasty in the 1980s. In 1984, at 58, he was diagnosed with AIDS and a shocked world learned of the disease that would take him a year later. Even then Hudson’s first concern was for his co-star Linda Evans, and an intimate scene required by a Dynasty script which they would rehearse and shoot together. Kijak’s last clips reprise movie scenes in which, as both a fighter pilot and ordained minister, Rock consoles a dying soldier through his last moments “in a shadowy light,” watching “as a door opens, passing through into a wonderful brightness,” transitioning “from darkness to light.” It’s the actor’s once-in-a-lifetime perfect blend of illusion portraying reality masked as illusion. It was, and is, as the title says, All That Heaven Allowed.

The Gullspång Miracle; Maria Fredriksson; Sweden/Norman/Denmark; 2023; 109 minutes

Let’s stay with those religious themes a bit. If you’ve spent too many hours of a long, long lifetime in darkened movie theaters, you’ve sat through (and learned to be wary of) an unending stream of dramas with “miracle” in their titles. The word still carries emotional heft, and you’ve surely discovered that some miracle movies work better than others. This writer’s first coming-of-age faith drama was The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima, a 1952 Warner Brothers version of an “inspired by true events” moment in the tiny Portuguese village of Fatima. (There, in 1917, the Virgin Mary appeared and spoke to three related peasant children, all under the age of 10, one of whom became a nun and recognized memoirist.) The movie had an impact, though Arthur Penn’s version of The Miracle Worker in 1962 had a far more lasting influence, at least on this viewer, in dramatizing how Anne Bancroft played the teacher who taught the blind and deaf Helen Keller (Patty Duke) how to fold her napkin at the dinner table, and ultimately, how to speak.

Fast forward to 2022, and the viewer’s hands-down miracle favorite, Miracle, an out-of-the-box Romanian thriller by Bogdan George Apetri, in which a smart police detective solves the kidnapping and near-fatal beating of a novitiate in training. The young woman was being driven to a hospital for an abortion. She’s in a coma from the blows she absorbed under a bridge. Thanks to the detective’s astute sleuthing, we know the ordinary-looking taxi driver who thought he murdered her, and it’s possible she’ll positively ID her attacker through mug shots before she probably dies. Does she? Ah! The director gives us two possible endings and lets us choose whichever is more satisfying… and that in itself qualifies as a genuine movie miracle.

Which brings us to not one but two offerings in Tribeca 2023, each beckoning the viewer with its “miraculous” titles. You’d think this critic’s choice would be The Miracle Club, boasting three world class actresses demonstrating their always-admirable talents, but surprisingly it’s The Gullspång Miracle, a vexing inquiry into the lives of three totally unknown older women who aren’t actresses at all. Except maybe that’s not quite the case—maybe one of the three prominent women in Maria Fredriksson’s truly puzzling wild card doc, The Gullspång Miracle, isn’t telling the truth. It’s not impossible she’s fooling everyone including the director, which would make her the miracle storyteller of this whole fest.

Examine what we’re shown: Kari lives in the pleasant town of Gullspång, Sweden. As her visiting sister, May, recovers from injuries from rough water boating, the two women decide to buy and maybe share a home. The house selected contains three framed still lifes which Kari intuits as a divine marker of Christian Trinity. They’re introduced to Olaug Bakkevoll, a lookalike for another sister who they believe committed suicide in 1988. We’re given to understand Olaug lived in the same region but across a fiord from Kari. DNA tests reveal that Olaug is, indeed, a half-sister of Kari and May.

One theory posited is that the sisters, born in 1941 in Nazi-occupied Norway, were separated at birth by the Hitler regime. In that theory, Olaug was given a different birth date and raised by another family, becoming an army careerist. A second possibility, which the DNA test seems to rule out, is that the older sister simply didn’t die in 1988 (a body was never viewed by anyone in the family prior to burial) and is instead the on-camera Olaug. Yet another theory, voiced by one of the women, is that the DNA sample “was tainted with cat’s blood” and thus proves nothing. At one exasperating point we hear what is surely the director asking off-camera, “Is someone lying?” This viewer’s conjecture, which the director keeps circling and at the end hints at via a very peculiar voice recording, is that the key woman we’ve been looking at is either not playing with a full deck, or could be a total imposter who simply resembles her supposed kin. Which might mean the real older sister may have perished by (or in) a nearby lake, which is a final theory this documentary explores.

Importantly, we note (from a uniformed police officer) an autopsy report wasn’t shared with the family or the filmmakers. We see home movies of the sisters growing up and the resemblance between the woman is certainly there—but one of the filmic realities Sarah Polley taught us in her indelible cine-memoir, Stories We Tell (2013, critic’s choice), is that supposed home movies can be staged re-creations of a childhood, using carefully cast and directed professionals. There’s also a formal portrait of the mystery woman that Fredriksson’s camera locks on, ponders on, accompanying the subject’s stare with the kind of music stabs you once squirmed under in Hammer horror films.

The Gullspång Miracle is no miracle movie at all. What it is, is a superior and tantalizing mystery movie, full of false bottoms and curves-in-the-road, flavored by possibly unreliable narrators. The New York Times’ Natalia Winkekman, in her festival preview, greeted it as “my favorite world premiere this year, a dazzler in the documentary category.” Back in the 1940s, the director’s work would have been called a locked door mystery. That’s where something awful occurs in a room no one could have possibly entered. Mystery readers loved them. The Mysterious Bookstore in downtown Manhattan should put a poster in its window celebrating this mysterious movie, down around the same Tribeca apartments where Kim’s Video’s old bootleg movies are enjoying a second life.

Afire; Christian Petzold; Germany; 2023; 102 minutes

One day before Petzold’s prophetic new climate change drama rolled onto downtown festival screens, New York City was suddenly shrouded by the foul air of Canadian wildfires. In hours Manhattan’s Air Quality Index swelled to a “hazardous” 484, just short of a scale-busting 500, as city dwellers donned their K95 COVID masks and still breathed in the world’s worst air. Talk about timing. Afire’s subject is four young knockabout adults gathered in a secluded forest vacation home, mostly ignoring an approaching and painfully obvious front of forest fires, until their surrounding trees are afire and ash literally begins to rain down on their heads. Will any of them make it out alive?

Depending on how you look at it, this bizarre coincidence is either a publicist’s dream scenario or a nightmare beyond compare. Maybe it’s both. Petzold’s movie will open locally July 14 at Lincoln Center’s Walter Reade Theater, a prime uptown showcase. It’s won the Silver Bear Grand Jury Prize at the 2023 Berlin fest. It’s art cinema through and through. And it culminates with a half hour of unexpected and revelatory endings—one after another after another after another, all of which clarify even as they confound an opening hour of ho-hum talk by four adults oblivious to drastic climate change. This review is doggedly determined not to spoil Petzold’s ingeniously weighted conclusions. What’s clear is that Afire, like its core concept, is not a drama to be ignored. It’s priority viewing that uniquely demonstrates how a thinking and innovative filmmaker turns the catastrophes of his own country into global art. Maybe it’s just the air-conditioned movie you’ll pine for on a July afternoon topping 100 degrees.

Here’s a quick heads-up of the basics. Published author Leon (Thomas Schubert) and his photographer pal Felix (Langston Uibel) travel the coast of the Baltic Sea to Felix’s handsome family chateau. Nadja (Paula Beer, like Nina Hoss a Petzold regular) appears to be little more than an ice cream vendor whiling away her nights with lifeguard Devid (Enno Trebs). Leon’s task is completing a second novel, Club Sandwich, which sounds as bad as its title, before his editor arrives for a page-by-page read through. Leon is smitten with Nadja. Felix and Devid hook up. Felix’ idea of compelling portraiture is shooting his subjects head on and then from the back, as they watch the Baltic Sea. All four young people seem annoyingly lame. No one including the nearby townies is much bothered by the buzzing helicopters overhead and reddening skies peeking over the surrounding woods. You may be confounded by everyone’s complacency.

Petzold freely shared his inspirations for Afire with Film Commett’s Devika Girish in March, and two influences in particular are worth noting. Anton Chekhov’s 1896 The House with the Mezzanine is narrated by an idle painter who interacts with a similarly indolent writer. Chekhov’s setting is a formidable home owned by one creative, and Petzold condemns both as “total losers,” procrastinators who cannot seem to find either fulfilling work or love. In Afire all four housemates and the entire surrounding community feel next to morabund, oblivious to the peril burning its way toward them.

The second influence is a poem, The Asra, by Heinrich Heine, a 19th century German visionary. It’s recited in a centerpiece scene following the arrival of Leon’s editor, Helmet (Matthias Brandt). The essence of the poem is that a slave from Yemen dies when he falls in love with a princess. Petzold then begins dealing out a dizzying array of events that cinephiles will be debating long into the long hot summer of 2023. Viewers may hope that the lackadaisical, all-thumbs Leon (always smoothly acted by Schubert) finds a more potent subject to write about than Club Sandwich. You will not be disappointed.

The Lesson; Alice Troughton; United Kingdom; 2023; 103 minutes

“Writers are always selling someone out,” admitted the late Joan Didion, one of America’s preeminent essayists, novelists and screenwriters in the late 20th century. British director Alice Troughton has a doozy of a contemporary update in J.M. Sinclair (Richard E. Grant), a fabulously successful literary lion cocooned in a secluded English country estate. Sinclair has a staff of servants, the kind of art collector wife, Hélène (Julie Delpy), who appears born to govern a rich household, and a sulky, sullen son, Bertie (Stephen McMillan), who’s been short-listed for admission to Oxford. Helene’s hired a fresh Oxford grad working on his first novel, Liam (Daryl McCormack), to spruce up her son’s writing and interviewing skills. Being the height of efficiency, Hélène has Liam sign a raft of contracts including a non-disclosure agreement, and instructs the tutor to brief her after every lesson with Bertie.

The Lesson is artfully constructed with a prologue and epilogue that reveal far more than you’ll read here. It’s the flip side of Petzold’s Afire—yes, here’s an entire movie built around the writing process, revealed as a system despoiled by wicked duplicity and outright thievery that can destroy lives. Like any strident neo-noir that lives by its fatalistic wits, it’s a sinister treat that’s kind of delicious. (At one teasing point, we watch the author watching a 50s Brit noir with a killer femme fatale.)

J.M.’s credo is that there are no original ideas, that only ordinary writers attempt originality, and that “great writers steal.” He’s a walking PowerPoint of dopey advice and outrageous bromides, delivered with brute force authority by Grant, one of our finest screen chameleons. The young Liam views J.M. with some awe, but also pegs him as a fading superstar, and worse, as the charlatan he champions. The author and the tutor trade manuscripts. J.M. invites Liam to read what he positions as his latest novel. The tutor is filled with admiration for the draft, except for the ending, which he finds disappointing. JM flies into a rage, reminds Liam “you’re just my proofreader,” dismisses the tutor’s first manuscript as “airport trash,” and suggests he find a career in teaching. Liam’s gift as an academic and cultural wunderkind happens to be an uncanny ability to instantly memorize mountains of content without any idea of their meaning—a skill that will prove essential in Alex MacKeith’s cunning and tightly machined screenplay. Both men are prodigious drinkers, which will escalate into a murderous rage. Not surprisingly, the old-school author has zero computer skills while Liam’s a master techie—which will also prove indispensable in the neatly layered plot.

A more ominous story element involves an estate swimming pond in which Bertie’s younger brother drowned several years earlier for reasons that are family secrets. Another intriguing development lets us eavesdrop on late night peeks at the drunken novelist pleasuring the compliant Hélène, while she glances out their bedroom window over at a guest house window where Liam is openly spying on them. And she smiles at him. You can see where The Lesson is heading.

Or not. Like Petzold’s Afire, The Lesson has multiple surprises in its final chapters (which here carry screen numbers) and MacKeith’s concluding epilogue, which adroitly connects the dots to his opening prologue. Don’t underestimate the weight and importance of Delpy’s marvelously understated acting. She’s the puppetmaster who handily survives all the chaos she’s fallen into. Writers may always be selling out somebody, but watch—here’s one woman who won’t be sold out by anybody.

Sealed Off; Tianyu Jiang; China, Macau, United States; 2023; 17 minutes

Enough of these Petzold/Troughton escapades, entertaining as they are, that pussyfoot around pretend literary landscapes. It’s time to get serious about serious literature, and celebrate the best short in the 2023 Tribeca Festival. To fully embrace this enormously touching 17 minute drama, you need to be aware of Eileen Chang (1920-95), the Chinese essayist and novelist. Think of her as a first lady of Chinese letters, much like Marguerite Duras, for years France’s preeminent female novelist. Both were fierce feminists who formed their sensibilities prior to and during World War II, when Japan had invaded China and was laying siege to Shanghai and Hong Kong, several years before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Chang lived in these disrupted environs, where people’s lives were wrenched daily. She married and found work as one of Hemingway’s first translators into Chinese. Her fiction carries defining titles like Half a Lifelong Romance, Little Reunions, and Love in a Fallen City. Ang Lee’s award-winning feature, Lust, Caution, is based on a Chang story, and this short by Jiang was inspired by another Chang story whose title translates to “sealed off.”

The setting is a crowded trolley car circa 1939-40 in Shanghai, shown sometimes in black-and-white, sometimes in color, sometimes both. Hundreds of citizens either cluster to board. or walk to and from work, or avoid public spaces entirely – depending on the truckloads of Japanese soldiers rumbling through the streets. The two principals seated across from each other are played by Shijiu Liu (as a 25-year-old single student) and Zhenfei Chen (as a 35-year-old married businessman). Noticing an undercover spy boarding the bus and perhaps searching for a stray young woman to seize, Chen moves to sit beside Liu protectively, and engages her in conversation. She’s relieved by his concern as the spy moves away. The camera loves them both, instantly.

In short order we learn he’s stuck in a forced marriage and a career leading him nowhere, in very perilous times. He has two daughters and is desperate to start his life anew. She’s watching him, evaluating him. They’re obviously drawn to each other. We intuit that people say and do things in wartime they wouldn’t say and do in peacetime. The scripting is tight and the atmosphere—subtly blending their interior conversation shot in color with that monochrome exterior—is hypnotizing. You haven’t eavesdropped on many slightly surreal conversations that pull you in so fast. He asks for her phone number, but can’t find a pen to write it down. We see she has a pen in her purse. Will she give him her pen to take down her number?

Sealed Off was shot in Shanghai’s Chedun Film Park, a working movie set (with a period trolley!) specifically fashioned for filmic re-creations of China’s past glories and tragedies. What a smart production idea. The director had only four shooting days, maneuvering hundreds of extras. Credit Aaron Peak with the extraordinary color grading and other post-production magic. From the beginning of movies, shorts have been the calling cards of every filmmaker with a dream. Sealed Off should open up worlds for Tianyu Jiang.

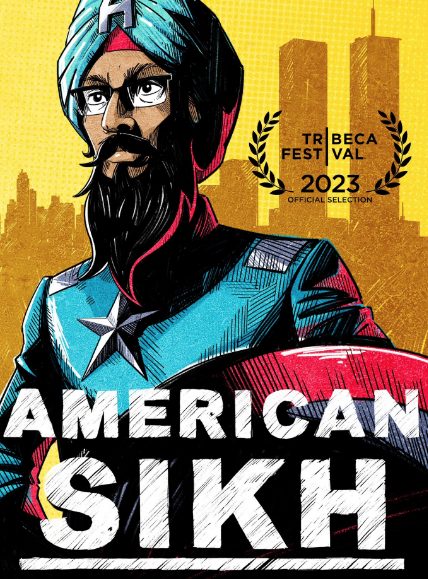

American Sikh; Ryan Westra, Vishavjit Singh; United States;2023; 10 minutes

Look at the poster. Better than any other content in any medium in the festival, it shows how and why the Tribeca Film Festival was literally born in the ashes of the 9/11 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center, in the spring of 2002—“to spur the economic and cultural revitalization of lower Manhattan, through film, music and culture.” It’s co-director Singh’s life journey, animated into a lively mini-movie that shows NYC as the sanctuary city it’s always been and remains, full of sharp elbows, a big heart, and eight million stories.

Following the assassination of prime minister Indira Gandhi, in 1984, Singh journeyed back to America with his family to attend college in his home country. But in his Sikh turban, he was derided as a “genie,” “raghead,” or worse. So Singh lost the turban, cut his hair and trimmed his beard, exploring multiple philosophies and identities. A month before 9/11 the turban went back on, and then the towers went down… and Singh became not just an object of scorn but a menace to society.

The image of Captain America: The First Avenger gave Singh the Big Idea that would change his life. He simply changed into a turbaned and costumed Captain America. The pros at New York Comic Con nodded in approval to Singh’s updating of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby’s original superhero and Nazi fighter. On the streets of Manhattan, where costumed characters pass unnoticed day and night, Singh has discovered a measure of acceptance, occasional applause, even once-in-a-blue-moon adoration. He’s learned that a cartoonist can become a performance artist, a lecturer fighting intolerance wherever it raises its ugly head. In this handsomely drawn and briskly paced lesson in democracy, he’s the American Sikh and the rousing hero of a short “dedicated to every American who’s ever felt unwelcome or unwanted.” And don’t you dare forget it.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 61st New York Film Festival, September 29-October 15.