Godzilla, Or How to Make a Monster Popular

The fearsome Godzilla continues to strike terror 69 years after its debut. The original film helped launch a genre of monster films (kaijū eiga) both in Japan and the United States. These films inspire fear but also creativity, Gareth Edwards, who directed the 2014 American reboot of “Godzilla”, would start in the monster genre through his indie hit “Monsters.”

Godzilla’s continuing success lies in the ways the films have resonated both with Japanese and American audiences. The ability, or inability in some cases, to tap into current sentiment will determine if the monsters will roam the earth for another 69 years.

I. Gojira and Godzilla

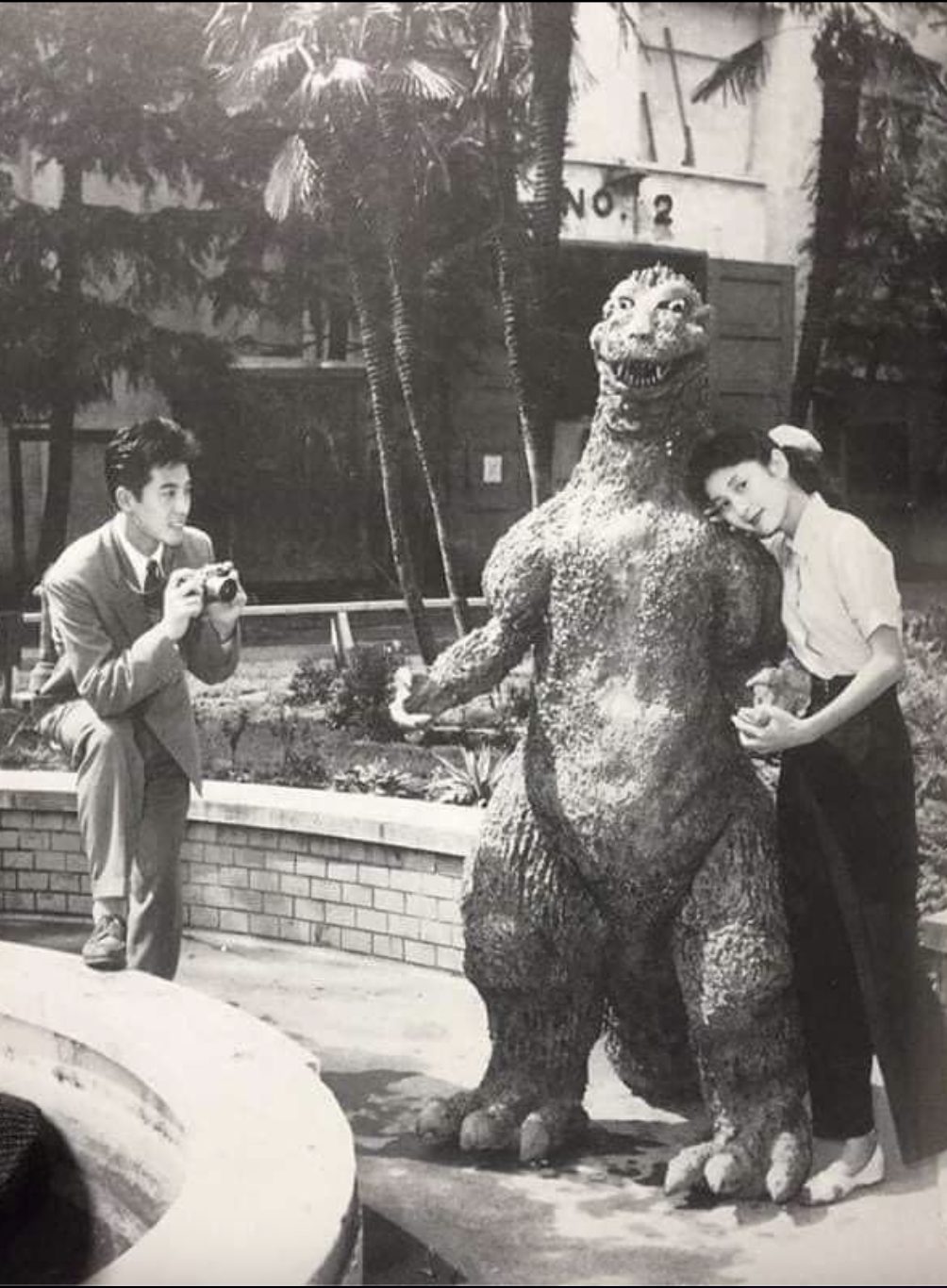

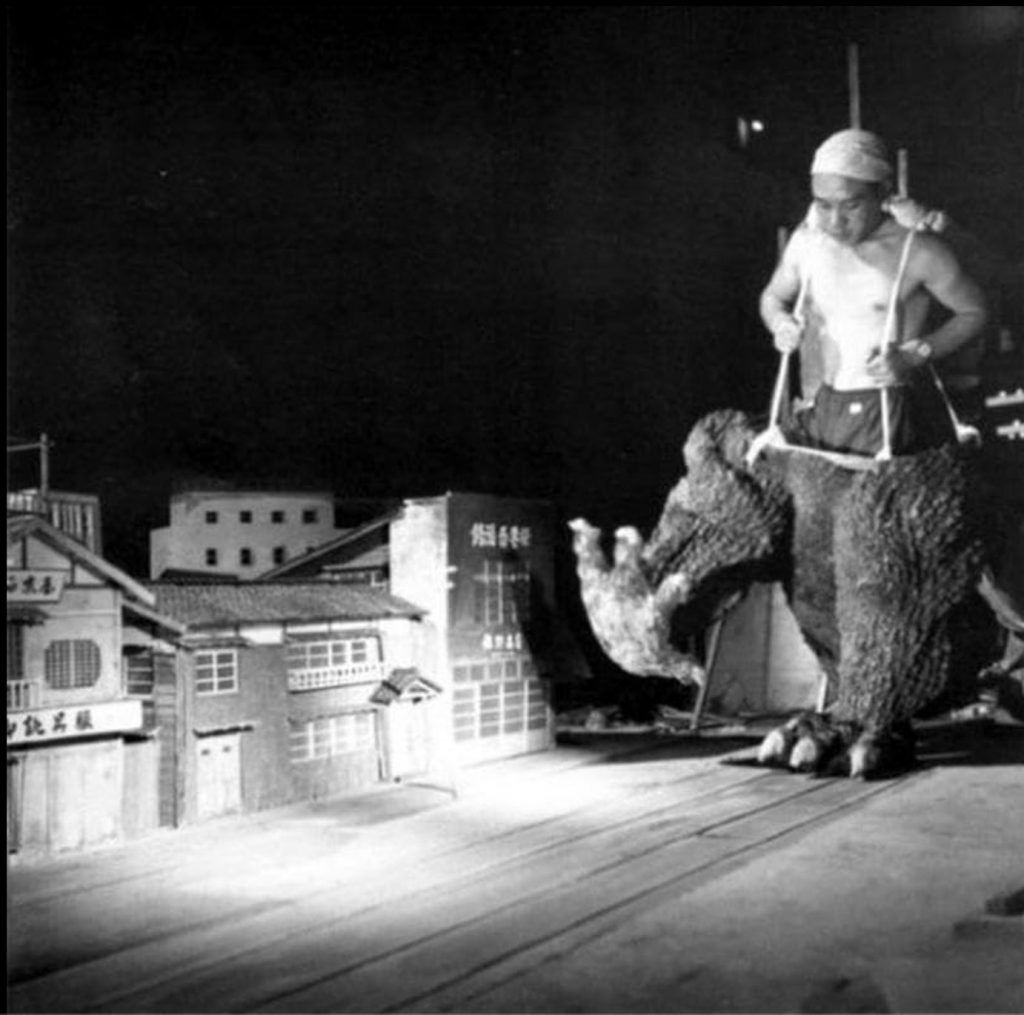

“Godzilla” started as a cultural fusion project. The original Japanese title, “Gojira” acts as a combination of the Japanese word “Kujira” (whale) and “Gorira” essentially the American word “Gorilla”. The occupation of Japan by the American military only ended 2 years before 1954, and American films were still heavily popular in Japanese theaters. This led a producer from Toho Co, Tomoyki Tanaka, to see a 1953 film about a gigantic creature awoken by the atomic blast called “The Beast from 2000 Fathoms” based on a Ray Bradbury story.

What led “Gojira” to have a longer legacy than “The Beast from 2000 Fathoms” lies in the sentiment of its native audience. A month before Tanaka pitched his idea, U.S hydrogen bomb experiments near Bikini Atoll contaminated a Japanese fishing vessel and their food supply. The event fueled a strong anti-nuclear movement within Japan. The vague exposition of “Operation Experiment” awakening the monster in “The Beast from 2000 Fathoms” was replaced by the destruction of fishing boats and explicit references to hydrogen bomb testing as to why Godzilla has risen. The film did not shy away from these fresh wounds.

This sparked a strong reaction from Japanese audiences. Despite the creature attacking Japanese vessels and cities, audiences took to connecting Godzilla to their feelings about nuclear weapons. It represented both the destruction of the atomic bomb and the reaction to that destruction. Godzilla was an antagonist audiences felt sympathy for, which would likely drive the direction of future sequels where he served as humanity’s ally.

Historian Anne Allison speculates that the film gave Japanese audiences a fantasy outlet, focusing on the Japanese as victims of Godzilla. Tanaka would later speak directly to this point“…people have to suppress their anger, and Gojira is a substitution for this. It satisfies everyone’s desires for destruction.”

But did it satisfy American audiences? A heavily edited version was released in 1956 known as “Godzilla: King of the Monsters!” by Toho’s new LA subsidiary. This meant most of the live-action segments, were replaced with American actor Raymond Burr reacting to Godzilla’s attacks portraying an American reporter. One example included cutting a scene where the public argues with the island chairman over whether Godzilla’s relation to H-bomb experiments should be made public for fear of, “hurting foreign relations.” One producer, Richard Kay, aptly explained the massive change, “We weren’t interested in politics, believe me. We only wanted to make a movie we could sell…We just gave it an American point of view.”

While American critics panned “King of the Monsters!”, Toho and Richard Kay understood the monster film craze in America at the time. “King Kong” a film nearly two decades old at the time, was rereleased in 1953 (Another inspiration for Tanaka). The same year as “Gojira,” Americans loved “Them!” a movie about giant nuclear ants. They weren’t treated as political dramas but as camp attempts at horror. American audiences shared a desire for destruction and what was considered “art house cinema” for being foreign language films became po cinema. As intensely as it deviates from the original, it ultimately got approved by Toho and led to the emerging American fanbase for Godzilla. Even as the series wildly deviated and retconned itself, “Gojira” would always serve as a point of reference for the decades to come.

II: Godzilla Rides Again in Japan, Stumbles in America

Toho took these respective reactions as lessons. In the list of various sequels, known collectively as the Shōwa Era for occurring under the reign of Emperor Shōwa, Godzilla often plays the defender of humanity, fighting against other monstrous foes to protect Japan. He slowly over the next two decades went from a mythic unknowable force of nature to a more outwardly friendly guard. Over time, the series turned more towards child audiences

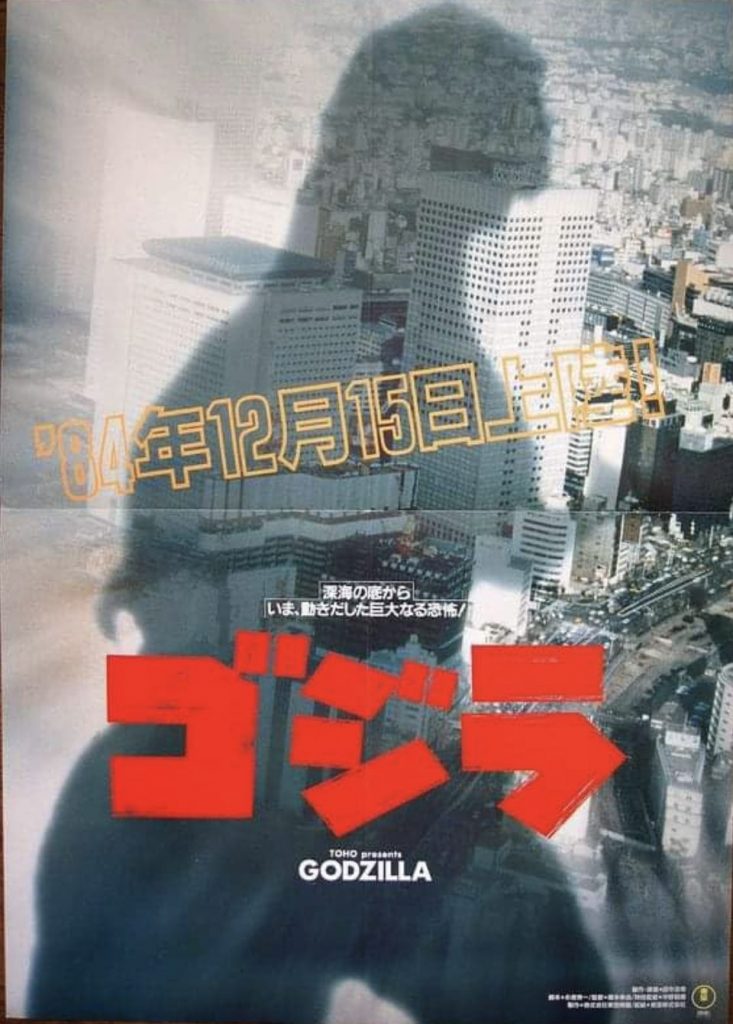

When Tanaka was asked back to reboot the series in 1984 for, “The Return of Godzilla”, he steered it more towards adult political drama. He took inspiration from the Three Mile Island Incident, a massive nuclear meltdown in Pennsylvania. The film serves as a Cold War drama when Godzilla nearly instigates a nuclear war between the Soviet Union and America.

Similar to “King of the Monsters!” New World Pictures created a new version of the film with Raymond Burr and released “Godzilla 1985.” The film majorly changes the portrayal of the Soviet side, deleting a scene where a Soviet general attempts to stop a nuclear missile launched by his side at Japan. Dr. Pepper paid 10 million dollars for added produce placement. The Japanese version received moderate praise, but the American remake was panned by local critics. Critic Roger Ebert speculated if the edit was an attempt to manufacture campiness, calling it, “ a bad movie with aspirations of being a good bad movie.”

The later American attempt to revive the series in the U.S. received even worse reviews from all audiences. Roland Emmerich’s 1998 “Godzilla” creates a creature more animal than mythic, as well as removing Japanese/American political subtext from the films. The creature even got dubbed “Zilla” by Toho to distance it from their star. Zilla starts as an iguana irritated by French nuclear tests, who decades later ravages New York to lay eggs. The creature represents an invading force only stopped by the collective power of the United States military.

The failure of Emmerich’s film came from deviating heavily from both the political and mythic themes of the series. The film represents Emmerich’s interpretation, as his contract with TriStar agreed Emmerich and producer Dean Delvin would have full authorial control. His attempt to deviate so heavily from the 1954 film, even more than “King of the Monsters!” led to an intensely negative response.

Toho felt they needed to reboot the series again with “Godzilla 2000” or “Godzilla Millenium.” This era came and went, lasting only 5 years, returning to the fantastic of Godzilla fighting with Aliens and superhuman mutants. They all received English dubs but were still treated as camp popcorn films, with more focus on the special effects and monster fights.

III. 21st Century Godzilla and the Homeland

In 2012, American company Legendary Pictures acquired the rights to produce a Godzilla film. They were well known for their association with Christopher Nolan’s Batman films and had another giant monster-related project, “Pacific Rim”, in the works. They hired Gareth Edwards to direct, who as previously mentioned created his film around giant monsters. Edwards, unlike the previous American adapters, treated the original 1954 material with grave sincerity. His vision of “Godzilla” has roots in the 1954 film but with, “an American point of view,” as Richard Kay put it.

Edwards’ film can be described in two parts, the human drama surrounding natural disasters and the cinematic battles between two giant monsters. The human drama takes up most of the film, in the form of U.S. soldier Ford Brody trying to reconnect with his family while constantly running into Godzilla. The film’s imagery is influenced by multiple natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina and the Fukushima disaster. But the universal disaster themes take center stage over political themes.

To return to Allison’s point, about the original 1954 film representing Japanese feelings of victimhood, Edwards continues that trend but with American feelings. Godzilla’s origin story no longer revolves around American H-Bomb testing, with the bombs retconned as attacks against Godzilla. Any mention of Hiroshima was removed, per requirements by the Pentagon who edited the script according to British Journalist Tom Secker.

The American military and shadow organization Monarch serve as the protagonist forces. They are only causing trouble when the enemy kaiju, the MUTOs, steal their nuclear warheads for their nest. The only similarity to Emmerich’s film, the monsters are foreign invaders who seek to repopulate. The ending, Godzilla defeating the MUTOs in San Fransisco, contains a news broadcast speculating if Godzilla is the “Savior of Our City [San Francisco].” Godzilla does not defend humanity, he defends San Francisco and America.

The series that would ultimately spawn from this film, dubbed “The Monsterverse,” would shift focus toward the kaiju fights rather than human drama. But the incorporation of pro-kaiju eco-terrorists and Hollow Earth habitats form a world of fantasy political situations that lean pro-America. The situations only serve to move Godzilla around the world rather than make a statement.

The 2014 film pushed Toho to create their version of a 21st-century Godzilla in the inverse way the 1998 film had. Toho hired Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi, writers of the famous anime “Neon Genisis Evangelion” to create “Shin Godzilla.” (New/True Godzilla) In terms of political themes, Anno and Higuchi focus on a slow bureaucracy struggling to respond to the crisis of Godzilla. Slow debates between government officials juxtaposed with Godzilla’s rapid city destruction. The United States shows up as well, eager to take over from Japan and quickly nuke Tokyo to stop the monster.

The film’s ending has Japan’s various scientific, military, and construction agencies working together outside of U.S. permission to defeat Godzilla. A characteristically unsubtle nationalism theme scores the film, one that still exists in the original film. It feels as if Anno and Higuchi saw the 1954 scene arguing if the Japanese public should know about Godzilla, and turned that into a feature-length film. “Shin Godzilla” received praise for its themes from former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, “I think that [Godzilla’s] popularity is rooted in the unwavering support that the public has for the Self-Defense Forces.” Godzilla was the threat not the defender of Japan, yet he strengthened the image of the JSDF even better than Edwards or Emmerich tried with the U.S military

Despite the political satire taking shots at America, “Shin Godzilla” received praise in both Japan and the United States. With a limited release in America, it made back two million dollars in ticket sales. American reviews like Elizabeth Kerr in The Hollywood Reporter tended to focus on the creature effects but still praised the, “…delicate spoof of disaster films.”

IV. The Heart of Godzilla

Godzilla represents more than just anti-nuclear politics and monster fights, the variety of films in the last 69 years should hopefully prove. Despite Tanaka taking inspiration from early American stop motion cinema like “King Kong,” American studios and writers have such a drastically different interpretation of the beast. Even when directly adapting Godzilla films, the changes for American audiences create a different tone for the film. This franchise reveals a history of both American and Japanese cultural subtext, along with how these messages translate to other cultures.

What saves the series is the ability to reinvent itself successfully. But to do that comes from understanding what made the series successful in the past. Not just cynically working to maximize monster fights, a “Monsterverse” will only last so long. Instead, examining the cultural context of the past and the present can turn a disaster film into a long-lasting piece.

This history remains a lesson not just for studio movies, but also well independent filmmakers. Before the studios were involved, “Gojira” started as a man thinking of the foreign films he saw and wanting to make a version relevant to Japan at the time. The film and the many sequels have gone on to inspire a variety of filmmakers. Godzilla Fest happens every year on November 3rd, featuring short and feature-length films by individual creators and those who’ve worked on previous Godzilla films. The fest celebrated the 50th Anniversary of “Godzilla vs Megalon” and Takuya Uneshi, 3DCG Director for “Shin Godzilla” released a short remake of that film online.

Ironically, it isn’t intentionally trying to make your film timeless and non-contextual that makes it memorable. Japanese and American audiences still remember Godzilla today as the criticism of nuclear weapons nearly 70 years later. Humor and exaggerated fight scenes play a big role, but the Godzilla films have always been about taping into the heart of the moment.

Related Articles: Godzilla stomps into US theaters for the first time in six years with the first-ever US screening of 2002’s Godzilla X Mechagodzilla, Five Asian Horror Masterpieces to Give You a Fright