America’s Largest Documentary Festival – Nov. 8-26

Anselm Kiefer, Liv Ullmann, Little Richard, Jack and Sam Top DOC NYC

How does one approach a film festival too big in its 14th annual edition (100+ features and 100+ shorts) to ever watch in its entirety? This year your viewer selects one sliver of DOC NYC—personalities—and watches for the ones that shine the strongest lights. This critic’s feature choices are a fine artist, an actor/director/biographer, and a rocker. The first two live on, the third has passed. Each has broken through traditional boundaries not quite like anyone else. Their work baffles and stuns and shakes us. The directors have condensed each life and its countless achievements into biographies running less than two hours each. And these cinematic biographies baffle, stun, and shake us to our very souls, even as they enlighten us on the mystery, magic, and lasting power of their subjects. Jack and Sam, the subjects of a 23-minute Critic’s Choice short, are 98-year-old Holocaust survivors whose lives—and whose very survival —also shake us to our souls. Make no mistake, the cinematic impact can be the same, or even greater. It’s just the running time that’s shorter.

DOC NYC’s 2023 selections showed through November 16, downtown at the IFC Center, School of Visual Arts, and the recently renamed Village East by Angelika theaters. They also continue as virtual selects through Nov. 26. Two Lifetime Achievement Awards have been presented: to Deborah Shaffer, a documentarian on social issues since the 1970s (her work includes the Oscar winner Dr. Charlie Clements, The Wobblies (recently added to the National Film Registry), and To Be Heard, (winner of the Grand Jury Prize at the inaugural DOC NYC). And to Michael Moore, whose career includes the Oscar winner Bowling for Columbine, the Emmy winner TV Nation, and Fahrenheit 9/11, which remains the highest grossing documentary of all time. Rounding out the honorees as the Leading Light Award winner is Erika Dilday, Executive Director of American Documentary Inc, former Executive Director of Maysles Documentary Center, and exec producer of POV and America Reframed.

Here are Critic’s Choices:

Anselm; Wim Wenders; Germany;2023; 93 minutes

The Artist and His Work Anselm Kiefer is the most internationally recognized and debated post World War II German artist living and working today. His work encompasses painting in gouache and watercolor, photography, artist’s books, engravings, installations, and sculpture. He was born in a hospital basement during an allied bombing raid during the last desperate days of the Third Reich. Initially a practicing Catholic, Kiefer was aware of the Holocaust but wasn’t directly involved in it; his father was an art teacher and served in the war. In 1965 Anselm switched from law to art studies and had his first solo exhibit four years later, introducing his apocalyptic settings. One key influence was Joseph Beuys, a conceptual landscape painter steeped in symbology. He planted the seeds that led Kiefer to blend oil and acrylic with lead, fabric, copper and gold leaf, ashes, straw, snakeskins, glass shards, dried sunflower stalks, dirt, sediment, human hair and leaden books weighing upwards of 600 pounds. He has a warehouse filled with carefully boxed ‘found materials.’

The artist’s first two exhibits in Manhattan were with Ileana Sonnabend and Marion Goodman, both Jewish gallerists. Kiefer’s first exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1988–89 required MoMA to reinforce its walls to hold the massive lead weight of 85 works of “heavyload maximalism.” But he’s also shown 40 more traditional watercolors at Manhattan’s Gagosian gallery, as well as in Jerusalem. Many of his assemblies reference Merkabah, a form of early Jewish mysticism. Through the decades, says professor Andreas Huyssen, Kiefer’s strategy has produced a “nationalistic imagery of a kind of original sin of the post-Auschwitz era.” The reviews in Germany on Kiefer’s fusion of memory, history, and mythology can still be severe and negative. Writing in The New York Times three years ago, author Karl Ove Knausgard acknowledges “the gravity we all know but rarely acknowledge” when we encounter Kiefer’s art. He adds, “we fall silent.”

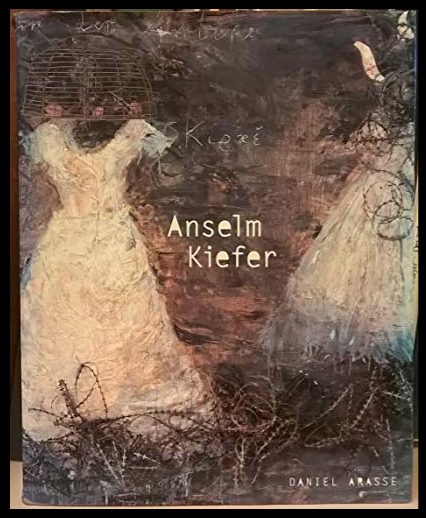

Wenders’ 3D Movie. More than anything else, it’s the dress you’ll remember. It turns up constantly, tucked into scene after scene, past and present, of Wenders’ breathtaking plunge through the early career of this profoundly unsettling myth maker. Either Wenders or Kiefer, or both, won’t let that dress go. This ‘headless woman’ even finds her way onto the cover of Daniel Arasse’s landmark analysis of the artist’s life (Abrams, 2001), which is essential reading for fully understanding Kiefer’s artistry. Whole rooms of these dresses spout heads made of birds-nest straw, bent books fashioned from lead you couldn’t begin to lift, barb wire, minis of his leaning buildings, even a whole planet. She’s Kiefer’s Lilith, a name you may recognize as Adam’s first wife (before Eve) and a Kabbala figure of demonic, sexually insatiable mythology. Lilith is a child killer in folkloric legends as unsettling as some of Kiefer’s own Shoah interpretations, She’s a succubus and symbolizes the eternal threat Kiefer has spent a lifetime trying to shake. In all their heady disguises, the white dresses stand around like German femme fatales, death dealing power figures that forever haunt Kiefer’s mournful melancholia.

Wenders’ enthralling documentary dissects the artist’s early life, and many of his famous works, entirely through 93 minutes of the artist’s memories and perspectives. He’s narrator and host, on-camera and voice-over, as seen at 79 but also enacted by his middle-age brother, Daniel, (quite striking as a younger version of himself) and as a 10-year-old child by Anton Wenders, the director’s bright-as-a-button grand-nephew. Talk about subject and director being fused-at-the-hip and on the same page. Most scenes are focused on Kiefer’s interpretive works of World War II and the Holocaust. We watch the younger Kiefer strap his rolled early paintings onto the roof of his VW to haul down wintry highways to Beuys. Kiefer called himself a “new reactionary.” Fields of wheat bear the raw, permanent imprints of tank treads. Tunnels and staircases lead to crematorium doors. Viewed on a theater screen as tall and wide as many of the artist’s gigantic canvasses, projected in 3-D, they are staggering. (3D is the only way Anselm is being released, starting in Manhattan December 8 at the IFC Center and the Walter Reade Theater.)

Wenders builds his chronology with care and insight; he adroitly bipacks and tripacks works-in-progress with their history—vivid post-War footage of children playing in Germany’s urban reconstruction. Yet Kiefer doesn’t appear an angry or threatened man. Trim in black tee and black jeans, chewing on a cigar, he slathers paint from an elevated scissors platform as handily as he wields a blowtorch at ground level, burning fire effects into his morbid imagery. We are as deep into the creative process as any artist doc has taken us. Two figures Kiefer cites as drawing inspiration from are the Romanian Jewish poet Paul Calan, who we hear reading from Death Fugue, and the philosopher Martin Heidegger, for whom Kiefer created a monograph tracing the stages of Heidegger’s brain cancer. Like them, Kiefer “keeps trying to grasp the unimaginable” in all his Shoah translations.

It’s not surprising he’s a reader, a researcher, an explorer with camera in field and forest, the more mammoth the better. “If you build something big, failure is already part of it,” he growls. We marvel how his work spaces have grown from a two-story brick factory in Germany to a sprawling 200-acre indoor/outdoor facility in southern France, housing 36 gargantuan installations. Plus a Paris studio. Kiefer uses a bike to get around it all. There are whole fleets of decomposing fighter planes and attack submarines resting here. It’s Nightmare Art and in 3-D it can feel overwhelming. The mind boggles.

To his credit, Kiefer has entrusted his director to hold back nothing, including a brief series of “Occupation” photos taken in 1969, in which Kiefer posed giving a Nazi salute, as part of a thesis for his arts education degree. Many in the Jewish community have never forgotten nor forgiven this. Actress Jane Fonda can tell you that her trip to Vietnam, three years later, in which she condemned US bombing, earned her the lifelong nickname “Hanoi Jane” among some living war vets. Anselm’s premiere distributor, Janus Films, is surely aware this is probably the worst season imaginable to be launching a doc on the planet’s most controversial Holocaust translator.

Wenders, whose long and distinguished directing career has included a similarly striking 3D tribute to the dancer/choreographer Pina Bausch, doesn’t overtly weigh in on how he feels about Kiefer and his work. (If Werner Herzog had directed this doc, you’d surely know.) Which is all the more reason to examine how Kiefer himself adds up his life. Stretched out in his usual yoga position, alongside the director’s school age version of himself, the artist confesses he’s been “banished…not on the run but on the way.” We watched him as a boy walking a tightrope, now we see him again, as an old man, walking on a tightrope across a projected WWII abyss of bombed-out Germany. At nearly 80 he’s nimble enough to do it, seemingly without a safety net. We know Kiefer has never had a safety net protecting his art. But then the artists you carry around in your head through an adult lifetime never seem to.

Liv Ullmann—A Road Less Traveled; Dheeraj Akolkar; Norway; 2023; 131 minutes

Cate Blanchett, among the top actors who’ve been privileged to be directed by Ullmann in Broadway and off-Broadway dramas, is remembering her experience of playing Blanche in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. The revival played a three-week run at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in the winter of 2009, and tickets, which were scaled at a mere $40, quickly soared into the thousands. This writer stood in line six hours the day the box office opened, hoping to score a pair for himself and a daughter. Alas, the house manager announced “completely sold out,” and 99% of the line, crestfallen, moved away. But a few dozen of us remained where we stood, maybe unwilling to plunge back into the cold. We figured we’d ask about standing room, or turnbacks, or something. At that point the manager returned to an almost empty lobby and quietly announced we should all hold in line, that Ms. Ullmann and Ms. Blanchett had given permission to place cushion seats on the stage floor, flanking the action, at $40 each. And so we got to sit at her feet, brushed by Blanche’s slip, as Cate sweated over us for nearly three hours. It was not just the best off-B’way bargain ever, but maybe the most unforgettable theatrical night of our lives. This review humbly acknowledges their generosity.

Here, the British documentarian Dheeraj Akolkar (born in India) expands the scope and scale of his Liv and Ingmar, a critic’s choice at the 2012 New York Film Festival. In that doc, Ullmann was the sole narrator and on-camera presenter, describing not just her eleven movies with Ingmar Bergman—starting in 1966 with Persona—but the five years in which she and Bergman lived together and had a daughter, Linn. (He fathered eight other children with seven wives.) Liv and Ingmar concluded with the last day of Bergman’s life in 2007, at his remote home on Faro island in Sweden, when Ullmann visited him and he gave her a final note, tucked into a child’s teddy bear.

Liv Ullmann—A Road Less Traveled focuses on how Ullmann transcended being the “painfully connected” muse, lover, and leading lady of a world class movie director. What’s most surprising is how many of Ullmann’s other movies she’s acted in that you may have missed (The Emigrants, The New Land) as well as films she’s directed (Private Confessions, Faithless, her adaptation of Strindberg’s Miss Julie) plus her Broadway appearances and directorial triumphs (A Doll’s House, Anna Christie, Ghosts, I Remember Mama), in addition to the biographies she reads from here at 85 (Changing and Choices) which may still be books-behind-books on your shelves. Cinephiles can catch up on her volunteer activities as Goodwill Ambassador for the United Nations’ UNICEF, and co-founder and honorary chair of the Women’s Refugee Commission. You’ll remember her honorary Oscar for Lifetime Achievement in 2022. Her latest news is serving as exec producer (along with Wim Wenders) on a gorgeous new documentary by Margreth Olin, Songs of Earth, about the joys of beholding old age in Norway’s splendid Oldedalen valley. Ullmann seems utterly tireless—fearless—in exploring roads less traveled.

As a film actress, her transformative picture was Persona (1964). Every filmmaker who watches Ullmann at 25 (playing a nurse) and her patient (Bibi Andersson) gradually change personalities until they literally merge as one, has to rethink the concept of women in film. Most recently, Noah Baumbach (Marriage Story) and Todd Haynes (May December) have acknowledged their debt to Persona and Bergman. Yet off camera Bergman wasn’t exactly a prince of a partner—his son Daniel, also a director, has noted “he’d say to his ladies, ‘when you’re pregnant, then I know you love me.’ Then he’d leave them.”

In a way, Bergman may have announced his departure from Liv at the end of their filmic journey together. Ullmann fans may recall her Q&A in Lincoln Center in 2005 (not shown in this doc), when she introduced her final film directed by Bergman, the made-for-television Saraband and the one picture he shot in digital. The radiant star told a rapt festival audience of her frustrations: “I always played scenes directly to Ingmar, who crouched right next to Sven Nykvist’s camera lens,” she wistfully recalled. “But with digital, Ingmar had to be across the room, watching a little monitor. I had several different cameramen filming me, and no Ingmar. I was lost.”

Akolkar’s fine doc is conveniently divided into three segments—Actor, Storyteller, Traveler—that will play comfortably in home streaming. It has estimable value for theater and film students globally, not only for Ullmann’s versatility in reinventing her life in so many interesting ways, but for a lifetime of performing secrets she freely shares with the viewer. Some of these seem trifling, but they’re not—like when Rock Hudson warned her away from a notorious Hollywood womanizer. The heart of her artistry comes in an interview with actress Lena Andre, who in Faithless leaves her husband and daughter for her lover. (The 2001 movie is about to be remade as a TV series with Andre.) Ullmann, directing her, remembers when Bergman instructed Liv to take a long pause before completing a painful monologue. Ullmann urges Lena to pause and remember “the tall, thin little girl she’s leaving.” And Lena does, and for a moment we glimpse her child, and the scene works, far more powerfully. And we realize how Ullmann has transitioned so successfully from actor to director…a road less traveled.

Little Richard I Am Everything ; Lisa Cortes; USA; 2023; 98 minutes

In Indianapolis in 1957, your critic first discovered Richard Penniman on late night rhythm-and-blues radio, beamed from the 50,000 watt WLAC station in Nashville. Though it was high on the AM dial, WLAC played music described by author Ralph Ellison as “on the lower frequencies.” Coming-of-age stuff you couldn’t hear anywhere else. A major sponsor was Randy’s Record Shop in Gallatin, Texas. One of their advertisers was an extinct brand of petroleum jelly. The Randy Wood cohort who spun the discs—often gut bucket blues recorded as 45rpm singles and Extended Play (EP) 45s—would let out a stutter-stop wail that sounded exactly like Tarzan of the movies. He’d do that whenever he discovered a newcomer as different as Little Richard, which was almost never. The three EPs pictured here were bargain-priced cutdowns that comprised his debut album, “Here’s Little Richard” on Hollywood’s Specialty label. They play great on a Denon turntable, and they’re keepers til the cows come home.

Lisa Cortes’s doc on this phenomenon is exhaustively researched and assembled like a fine vinyl disc. It earns the singer’s “I am everything” self-proclamation, while digging deep enough, pinching hard enough, that you may walk away after 98 blistering minutes agreeing Little Richard was indeed everything…and everything wasn’t enough. Cortes captures the ambiguities and distresses—the flip sides, the B sides— that the singer/songwriter/pianist felt and partly concealed nearly all his performing life. The smallest of 14 children raised poor in post-Depression Macon, Georgia, Little Richard slowly grew to become Billboard magazine’s Triple Crown Award winner, the Most Played R&B artist voted by DJs in Billboard’s Poll, and winner of Cash Box magazine’s Juke Box Operators’ Poll.

Then he watched as white singers from Elvis to Pat Boone appropriated his songs, his style, and most of his earnings. Mick Jagger barely gets a pass telling us Little Richard taught him how to work a stage. Ditto Paul McCarney, who learned that Tarzan-style yowl and climbed on the piano in his youth. Elvis Presley and Pat Boone sold more copies of Little Richard’s “Tutti Fruitti” than its creator. And when the New York Dolls’ David Johannson, in his full Buster Poindexter lounge lizard, puffed-up-hair mode, turns up next to Little Richard at an awards ceremony, you want to hide under your seat in embarrassment.

Little Richard was gay and alternately denied it and celebrated it, ultimately choosing to ignore it because high schoolers thought a Black man dressed as a glamor queen was kinda cool and shrugged it off—as their mid-century parents fussed and fretted more about Elvis wiggling his hips on The Ed Sullivan Show.

White teens in Indianapolis, like this writer, established Little Richard’s primary market. We hadn’t a clue that either this raucous singer or our fave movie star, Rock Hudson, were “homosexual,” whatever that meant, it was enough that we kinda understood, like Nona Hendryx in this doc, that Miss Molly “went all the way” because she “sure liked to ball.” Like Rock Hudson, Little Richard married, even paused his career to study to be a minister at Oakwood college. So how could Pat Boone’s version of “Tutti Frutti” outsell Little Richard’s? How could Jayne Mansfield, for pity’s sake, headline the 20th Century Fox movie, The Girl Can’t Help It, when all you can remember is Little Richard’s rockin’ title song?

Cortes opens a multitude of cumulative soul windows into how Little Richard became the lineal link to rock ‘n roll, or as he claimed, its architect. The road is endless when you’re two cuts above a traveling medicine show and trying to suck some oxygen away from unthreatening headliners like Lloyd Price and Fats Domino. It’s even more of an impossible dream to follow Janis Joplin and blow her crowd away, as Richard did. The singer’s inevitable bouts with hard drugs were mercifully brief and didn’t wreck his voice or his brain, unlike so many white rock legends who checked out at age 27. Little Richard made it to 87, and was still being rolled up to the piano in a wheelchair. No wonder one of his favorite audience bromides—maybe it was a putdown he learned from Nina Simone—was to loudly command an inattentive white crowd to just SHUT UP. And invariably, in shocked silence, it did.

Cortes, unlike a lot of music doc directors, has an unusually impressive gallery of talking heads beyond the expected relatives, lovers, musicians, singers and industry figures. The most informative, who don’t annoy the indelible black-and-white performance footage too jarringly or too often, are three Black scholars (Zandria Robinson, Jason King, Tavia Nyong’o) plus an ethnomusicologist (Fredara Hadley). They do the heavy lifting, deconstructing the many complex layers of a Black and queer performing life. King, who’s Chair of the Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music at Tisch, gets the line every review of this documentary will quote: “Little Richard was very, very good at liberating other people through his example, but he was not good at liberating himself.” Lisa Cortes blends this multitude of disparate voices into a headliner of a music doc.

Jack and Sam;Jordan Matthew Horowitz; USA; 2023; 23 minutes

These reviews began with a critique of a famous Holocaust interpreter, so it’s fitting they conclude with a deep bow to two Jews who survived the Holocaust together, and at age 98 are helping ensure the world never forgets it. Their experiences—and the impeccable artistry with which director Horowitz and animator Lukas Schrank infuse their imprisonment, one of their escapes, and their surprise reunion decades later—is sublime. Shorts rarely become more than a calling card for their directors, but they can have a long shelf life. And they do win Oscars. Bookmark this one.

Jack Warsak and Sam Ron were barely teens when they were imprisoned in the same labor Nazi labor camp in 1943. To stay alive, one buried the dead, the other shoveled coal. For nearly a year they supported each other, watching as countless innocents were transported off to Auschwitz, which they knew was the ultimate killing ground. Jack decided with 15 others to make a break for it, fleeing into forests where he was one of six who survived his pursuers for over a year. Back in the camps, Sam narrowly escaped being transported from Pionki to the Sachenhausen death camp at the war’s end, being liberated by American troops in 1945. The two men eventually migrated to Ohio, not having a clue they would settle 50 miles from each other. Until both attended a meeting of the United States Holocaust Museum in Miami, where Sam was the Honorary Chair and speaker. “I know that guy,” Jack thought. Minutes later, they clasped each other’s hands. And today, closing in on 100, they remain close friends, carrying the message to Boca Raton high school teens and more.

Director Horowitz compresses this miracle story into 23 minutes that don’t waste a second. He braids grim newsreel footage with an equally daunting moment from Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, with Schrank’s stark animation of frightening camp interiors and equally foreboding forest chases, into a capsule history any young person can quickly grasp. Too few Holocaust shorts have Jack and Sam’s triumphant victory. By finding each other then, they found the hope and courage that powered their survival. By finding each other now, they found Horowitz’ platform to make sure their story is never forgotten.

And it’s not just Horowitz who’ll get their story out. The lesson for every young documentarian is always, always try finding an industry figure who’ll champion your work. Here it’s exec producers Julianna Margulies, Sarah Silverman, and Silverman director Amy Zvi who’ll work their rolodexes to help move this short to the short list. That’s a first-rate team. Mazel tov.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the New York Jewish Film Festival, January 10-24, 2024.

Regions: New York City