New York Jewish Film Festival Jan.10-24

The Jew in Ecstasy and Agony: Lessons From the 33rd NYJFF

There are three critic’s choices, all features, in this 33rd NYJFF, sponsored by The Jewish Museum and Film at Lincoln Center. Before celebrating them, let’s give a shout-out to previous features in this festival saluted in long-form reviews by The Independent’s critic over the past decade. Collectively, they demonstrate the depth and diversity of Jewish life as it’s lived not just in New York City, but all over the world and all through history.

Starting in the order reviewed: Hannah Arendt, Koch, Joe Papp in Five Acts, AKA Doc Pomus, Ida, The Jewish Cardinal, Regina, Felix and Meira, Above and Beyond, The Outrageous Sophie Tucker, Let’s Go!, Moon In the 12th House, The Women’s Balcony, Past Life, Rabin The Last Day, The Law, West of the Jordan River, Mr. and Mrs. Adelman, Razzia, Who Will Write Our History, Echo, Seder Masochism, A Fortunate Man, Shared Legacies, Minyan, The Crossing, Aulcie, Those Who Remain, The Day After I’m Gone, The Lost Film of Nuremberg, June Zero, Shttl, Schäcten–A Retribution, Farewell Mr. Haffmann, and March ‘68. Plus several dozen shorts, including the first published review of Heaven Is A Traffic Jam on the 405, which won the 2018 Oscar.

Consider these three outstanding new pictures:

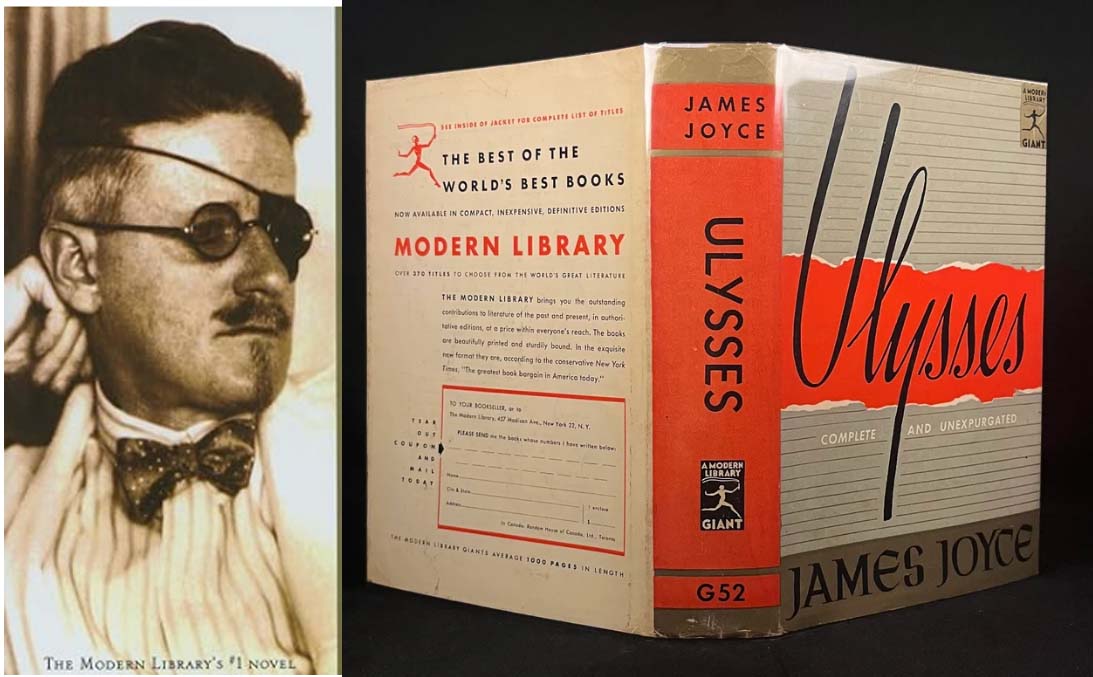

James Joyce’s Ulysses; Adam Low; United States; 2022; 88 minutes

Here’s a promise: If you watch Adam Low’s gloriously definitive 88 minute documentary on The Modern Library’s 816 page edition of its #1 title, you will never, ever be intimidated by Ulysses. What, you’ve still never read it? Take it from one of the endless scholars assembled on director Low’s jam- packed academic bench, who says, “you’re missing the novel that invented the modern novel,” And here’s an added bonus: If you’re Jewish, you’ll become instantly and intimately bonded to the first Jew (on his father’s side) to ever drive a 20th century novel as its narrator and central character. Do we have a deal?

America’s most unknown banned novel. To ice your commitment, let’s begin by noting that James Joyce’s mammoth tale covers just one day (June 16, 1904) in the life of its lusty Dubliner, Leopold Bloom. He’s a slick advertising canvasser—that’s the go-between guy connecting Dublin newspapers and signage companies with local city merchants. Mad Men’s Don Draper is standing on the shoulders of this inveterate womanizer and huckster. Bloom’s day is spent meandering the city, indulging 18 “episodes,” checking out the store window displays and the prostitutes plus a thousand and one other sights, and while his last episode is only six sentences in length, it runs 42 pages, a dazzling sexual soliloquy of sorts by Bloom’s pub-singer wife, Molly. Ulysses hasn’t yet raised the hackles and ire of most moralists in 2024, probably because so few have dared to explore its daunting text.

It’s not a book to be read under the covers by teens with flashlights, like, say, Irving Shulman’s Amboy Dukes, was back in the 1940s, in which the burning issue was whether some bonehead Brooklyn dopester would get the second button of Betty’s blouse undone. Unlike more refined literature of that era, like Orlando (the first transgender novel published In America), which contains no overt sex scenes whatever, Ulysses is rife with female/male couplings, described in microscopic, sweaty detail, all accompanied by the kind of explicit, panting beckonings usually seen scrawled on mens’ restroom walls.

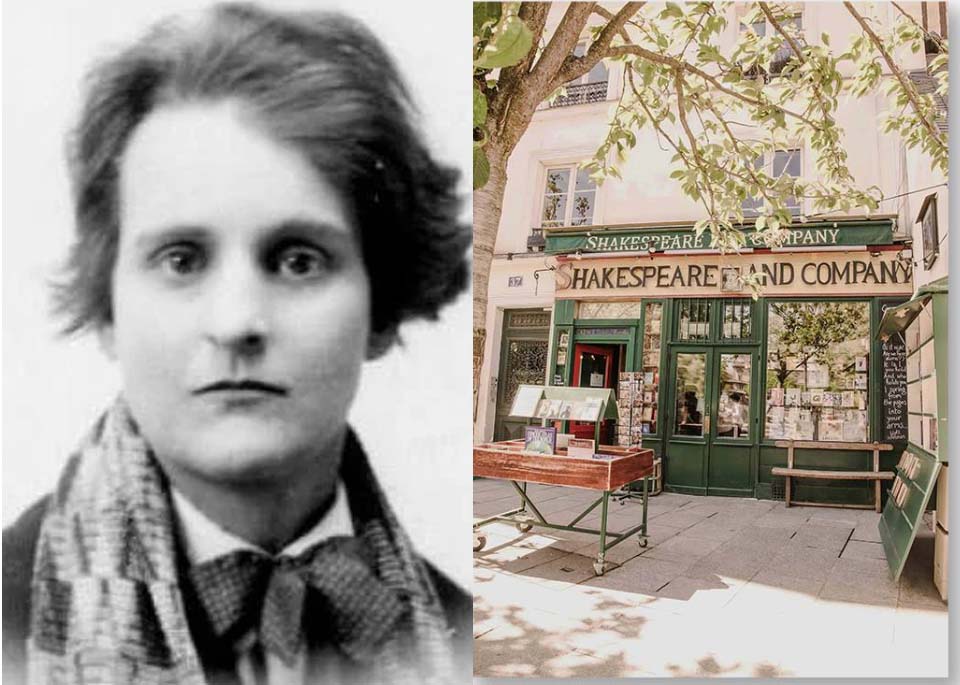

Ulysses’ manuscript was partially published by The Egoist, a London literary journal edited by Joyce’s patron, Harriet Weaver. It found a possible American publisher in New York’s avant-garde Little Review, a radical journal co-edited by a lesbian couple, with Ezra Pound onboard as foreign editor. The women began serializing the novel in 23 installments starting in 1918, until the text was charged with obscenity by the Society for the Suppression of Vice. In a court trial, the Society prevailed, the editors were fined $50 and Ulysses ground to a halt. Desperate for money after spending seven years writing his masterpiece, Joyce then turned to Sylvia Beach, also a lesbian and the Parisian founder of Shakespeare and Company Bookseller and Lending Library, who gladly published it in 1922, with a run of 1,000 copies. The Egoist followed with a first printing of 2,000. Both editions were sold privately by prospectus and subscription. In America, the Shakespeare and Company edition debuted publicly in 1933, and three years later in England.

The experts pile on. Salman Rushdie, Colm Tóibín, Anne Enright, Howard Jacobson. Writers, professors, scholars, biographers. even the first female obstetrician/gynecologist who today runs the Dublin hospital Joyce sets a scene in. There’s more marquee names deconstructing Ulysses in this doc than fill some major college faculties. And the overwhelming takes in observation after observation, sum-up after sum-up, are that the novel’s freedom of expression opened the door to a universe of uncensored writers, artists and filmmakers. If you walk in to Low’s doc with a better knowledge of ancient movies than you have of ancient literature, you’ll start thinking about who the parallel filmmaker to James Joyce’s endless accumulation of what Rushdie calls “the minutia of everyday life” might be. Dublin’s a city next to “a scrotum-tightening sea,” and Joyce clearly loves both. The one New York documentarian who was the cinematic equivalent of James Joyce’s Dublin and Ulysses was Jonas Mekas.

The Mekas connection. The Greenwich Village filmmaker, poet, critic, publisher and movie exhibitor is never mentioned in Low’s documentary. Mekas’ Anthology Film Archives, downtown on Second Avenue, continues since his passing in 2019 as the repository of lost indie cinema–20,000 works on 35mm, 16mm, and 8mm film, plus another 5,000 video and audio tapes and the world’s largest collection of paper materials (books, letters, manuscripts) relating to experimental cinema. Mekas practically invented the diary film–a record of everyday moments in his life. He began shooting these autobiographical home movies in 1969, many showing his immigrant’s life adjusting to the pace and rhythms of Manhattan. Like Odysseus in Homer’s Odyssey, the origin of Joyce’s novel, Mekas had journeyed from his roots in Lithuania and found a welcoming home in America.

From 1968-71 at ‘Avant-Garde Tuesdays,’ at The Jewish Museum in uptown Manhattan, Mekas’ Film-Makers’ Cooperative introduced and screened the work of leading-edge ‘underground’ directors including Maya Deren, Stan Brekhage, Jack Smith, and Shirley Clarke, along with his own shorts. The Independent noted his work in its Summer 1979 issue. Mekas’ 365 Day Project, a 38-hour video of his daily life throughout 2007, is as close a filmic companion to Joyce’s sprawling achievement as exists. “I can figure out James Joyce,” Mekas told an interviewer in Notebook, the year before his passing at age 96. Two years ago, The Jewish Museum presented the first U.S. museum survey of Mekas’ work, The Camera Was Always Rolling. He’s the one missing link in Low’s doc.

How James Joyce’s Ulysses pulls together author and novel. Low peppers his doc with visual cues that help the viewer through difficult and often obfuscating passages of Bloom’s comings and goings. Scenes with Kirk Douglas playing Ulysses in 1954 as the bare-chested seagoing adventurer contrast with revealing glimpses of Milo O’Shea, a close facsimile to both Bloom and Joyce himself, in a 1967 version, resplendent in bowler hat, walking stick and sly demeanor with women. Charlie Chaplin turns up in silent clips, reminding us of Joyce’s seven-month turn as an investor In the Volta Cinematograph, Ireland’s first dedicated movie theater which launched Chaplin to European audiences. Low shows streets and Joycean locations in Dublin then and now, just as Joyce explored them through street maps and his own encyclopedic knowledge of the city. There’s a playful music track sprinkling along as a jaunty rug under it all.

More importantly, the director doesn’t slight any of the supporting characters in the book. Stephen Dedalus, Joyce’s hero in Portrait of the Artist As A Young Man six years earlier, returns from Paris as a 22-year-old who shares four episodes with his mentor/father figure. Molly Bloom, James’ unfaithful wife, gets her due in the novel’s stupendous sexual climax, and we come to understand her contrasting role with Penelope, Ulysses’ ever-faithful wife in Homer’s Odyssey. Finally, Nora Barnacle, the chambermaid Joyce meets on that fateful day in 1904, beds, elopes with and finally marries, is given full credit as the author’s companion who raises their two children, endures her husband’s strayings and syphilis, as well as his obsession writing a novel she keeps hoping he’ll finish so he can move on to something that’ll support their family. Nora’s greatest triumph may be outliving her husband by ten years, and enjoying some of Ulysses’ s success.

See? In the time it’s taken you to read just one doc review, you’ve got the essence of what many readers avow must be the most difficult book in the English language. When Kirk Douglas made the movie in 1954, and more people were wading through Ulysses than do today, we’d say “read the book, see the movie.” Now it’s just the opposite—see Adam Low’s doc and you’ll buy or order your copy from Shakespeare and Company that night. And you won’t spend the rest of your life trying to future it out.

The Shadow of the Day; Giuseppe Piccioni; 2022; Italy; 125 minutes

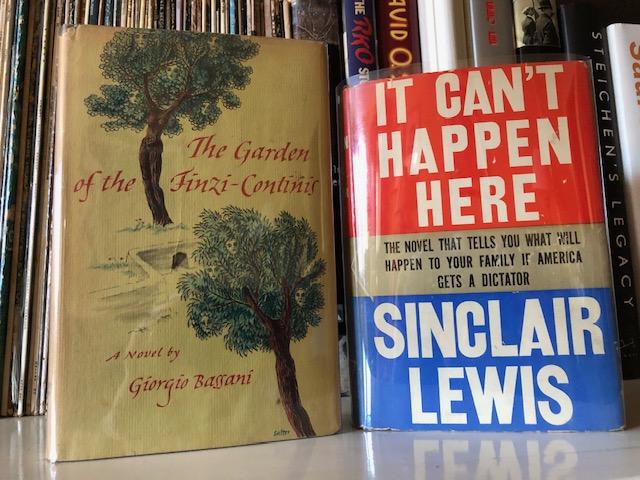

The gathering tides of fascism and dictatorial regimes before and during World War II have long been a priority of New York Jewish Film Festivals. The signature Italian film on the subject is Vittorio De Sica’s The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, which won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 1972, also garnering a screenplay nomination. It was based on the best-selling 1962 novel by Giorgio Bassani (which outsold The Leopard). De Sica focused on how Benito Mussolini’s “racial laws” slowly squeezed and then enveloped a rich and refined Italian Jewish family in Farrara, beginning in 1938, leading to their inevitable deportation to death camps. The menace of creeping fascism has been explored in pre-Holocaust screen dramas ever since. NYJFF’s most recent selection last year was Farewell, Mr. Haffmann, a tense, taut drama. This year it’s yet another superbly produced and acted variation, The Shadow of the Day. Even the title warns you what’s ahead.

In the pretty village of Ascoli Piceno (the director’s birthplace), Luciano (Riccardo Scamarcio) is a long-time resident, managing the town’s one upscale restaurant, his inheritance. He’s a World War I vet who walks with a permanent limp from a combat wound he suffered while killing Austrian troops, and he’s quietly aware of Mussolini’s gradual takeover of the government. His face is a smiling mask; it’s impossible to read Luciano’s thoughts, but he knows his place. One day a hungry young woman introduces herself as “Anna” (Benedetta Porcaroli). Luciano hires her as kitchen help and she quickly proves herself–she’s fast, intelligent and resourceful. Giovanni the cook (Vincenzo Nemolato), who has side hustles and may possibly be an Italian Jew, admires her work ethic.

Anna becomes a spark plug in Luciano’s dining room, impressing the upscale diners including the snarling Nazi official Osvaldo (Lino Musella). Hitler himself is planning a visit to the village, and Anna’s playing a role to stay alive. Forty minutes in she’ll confess to her boss that her real name is Esther Bauer, that her brother can no longer attend university, that her family’s fabric shop has been seized and closed, and that her parents have disappeared. Esther reveals her crumbling life…but she doesn’t quite reveal everything.

It’s an empathetic set-up and director Piccioni smoothly assembles the moving parts with ease. We’re settling into what’s becoming a staple of Jewish art cinema–the coming of Hitler– that’s searching for a wider audience outside the Jewish community. The Shadow of the Day may be the one to find it in this election year. (It’s not dissimilar to the prophetic novel that Sinclair Lewis, author of Babbitt, Arrowsmith, and Dodsworth, wrote in 1939, It Can’t Happen Here. That book carried the cover blurb “the novel that tells you what will happen to your family if America gets a dictator,” and was hailed in the Boston Herald’s prediction that “it may be called Mr. Lewis’ masterpiece.” The back cover blurbs include questions like “Will you lose freedom of speech?” Will your daughter lose her job?” “Will your husband be put in a concentration camp?”)

It won’t surprise you that Anna shortly gives herself to Luciano, the lonely restaurant owner, after declaring most of her truth. He’s an unlikely lover, but he’s also become her sole lifeline. Esther views Luciano as her “good guy,” her one chance at survival. He’s not hiding her yet in the restaurant’s cellar. Maybe he won’t have to. Will she be able to escape to freedom? Will he want to go with her? All these issues and more will come into play. Little wonder we’re starting to study and evaluate dramas like The Shadow of the Day as possible future playbooks for much of America.

More plot twists and turns await you in Piccioni’s absorbing and unpredictable drama. All of his ensemble cast work well in serving a severe and unrelenting premise of escalating fear and dread. This is a keeper in the 2024 winter of our discontent, a cautionary tale to consider with the utmost care.

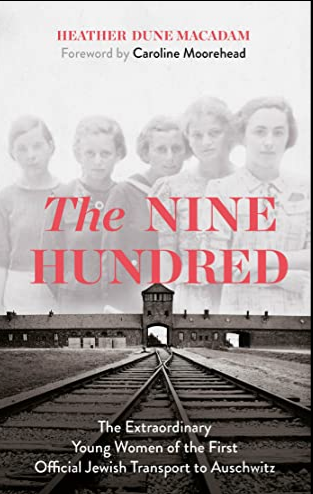

999: The Forgotten Girls; Heather Dune Macadam; United States; 2023; 86 minutes

“Whoever preserves one life, it is as if he has preserved an entire world,” says the Mishna (Sanhedrin 37a). That’s the message firmly embedded in Steven Spielberg’s Oscar-winning Schindler’s List back in 1993, illustrating how a deeply flawed industrialist, Oskar Schindler, played by Liam Neeson, saved 1100 Polish Jews from Nazi death camps. It became a winning format that global filmmakers have explored, especially in kinder, gentler forms. The Opening Night selection in this year’s NYJFF was One Life, in which an unblemished British stockbroker, Nicholas Winton, played by 86-year-old Anthony Hopkins, reflects back on how he (played by a younger actor) persevered in saving 669 Czech-Jewish children from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia.

The two dramas are 40 years apart, yet both represent similar lessons in wartime survival. Both carry the requisite message, “Never forget.” But what if you had no one to rescue you from the concentration camps? What if you lived through them on your own? This is where the right documentary can have the more meaningful edge. Heather Dune Macadam’s 999: The Forgotten Girls deserves as many spotlights as it can find, because it’s a real-life vision of survival–testimony by less than ten women alive after enduring the early 1940s locked in Auschwitz, Birkenau, and Ravensbrück death camps. Persuading you to invest an hour and a half studying the Nazi genocide of tens of thousands of girls and young woman is not an easy task, particularly for a critic with three grown daughters. But if you’ve never viewed a Holocaust documentary, this is the one you may remember longer than you want to.

Writer/director Macadam and her co-director and astute editor Beatriz Celleja waste no time in revealing how Heinrich Himmler, Hitler’s chief police administrator and second-in-command of the Third Reich, was planning to eliminate all Jewish women from 16 to 36, of child-bearing age, thus providing a Final Solution, an eventual end to the Jewish population. Starting in 1941-42, 999 young female Jews were rounded up in Humenné, Slovakia, for deportation by rail to Poland. Slovakia’s premiere was an antisemite priest who’d cut a deal with Himmler to literally sell off Jews who could bear children. Parents were told their daughters would be given six months of meaningful “work that will set you free,” with the savings the girls would bring home. Instead Himmler’s plan would link up the Humenné women with 999 more female Jews seized from another community, and another, and another. All were bundled into cattle cars bound for Auschwitz, where tens of thousands would perish in gas chambers and crematoriums, as well as from sterilization, typhus, and starvation.

But not all. The directors’ on-camera witnesses are in their 90s and all tell their stories cogently and matter-of-factly. Their minds are sharp and their memories very clear. What they explain is “heartbreak you can’t imagine.” Hunger was paramount and everyone worked to live—demolishing buildings, hauling out the dead, sorting and cataloging belongings. Good handwriting saved some lives. So did a viable singing voice and playing a musical instrument. Attractive women were assigned guard duty. The directors blend archival footage, school-girl photos, portraiture, illustrations, camp art, plus minimal re-creations, all quite nimbly, with their on-camera subjects. It’s not so much what you’re shown as what you’re told that may move you most.

There’s an urgency to this peerless, Academy-level filmmaking. Macadam and Calleja got to most of their half dozen subjects in the nick of time, starting in 2017 at a 75th anniversary meeting in Slovakia of first transport survivors. Each participant in this one-of-a-kind doc obviously wants her story to be remembered, as the ultimate warning against antisemitism and the growth of dictatorships anywhere on earth.

Nothing you’ll witness here has the star power of Schindler’s List or One Life. But perhaps 999: The Forgotten Girls is how an entire world is truly preserved.

This concludes Critic’s Choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks at Rendez-Vous with French Cinema in Lincoln Center, Feb.29-March 10.

Regions: New York City