Open Roads Italian Film Fest May 29-June 5

Two peerless movies-about-movies top New York’s essential art cinema festival

Next to the French New Wave, your critic’s cinematic tastes in the 1960s were forever shaped by Italian movies and their directors. The urban landscapes of Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Lina Wertmüller and Luchino Visconti profoundly influenced this viewer’s aesthetic. In the last decade, Marco Bellocchio’s opulent and operatic crime dramas (The Traitor, Kidnapped, Exterior Nights), all critic’s choices in The Independent, have matched the fearless movie making of Martin Scorsese.

This May and June, New York City has hosted at least five major film festivals—Film at Lincoln Center and the Museum of Modern Art’s 54th New Directors/New Films…FLC and AFF Inc.’s 32nd African Film Festival…the 24th Brooklyn Film Festival… 24th Tribeca Festival… and 24th FLC/CineCitta’s Open Roads. Each beckons different audiences and constituencies with a combined total of over 200 narrative dramas, documentaries and shorts. One is reminded of a promo poster that once hung in the lobby of FLC’s Walter Reade theater, showing an annoyed young Manhattan cinephile, dressed to the nines in goth black, sitting alone perhaps in FLC’s Cafe Paradiso, thinking “if he sees one more movie here, he can come live here.”

Open Roads, like ND/NF, stays small and select, inviting critics to advance screenings and curating less than two dozen features. Its 14-feature slate is easy, immensely pleasurable viewing, and nearly every one’s a keeper. Here’s three must-see critic’s choices:

Diamonds: Ferzan Ozpetek: 2024: Italy: 135 minutes

Ozpetek’s last appearance in Open Roads was eight years ago, but you’ll catch up fast on that and more than a dozen of his other pictures. The amiable Turkish-Italian director himself begins this utterly beguiling movie-within-a-movie. He’s gathered 18 leading screen actresses of his career for a luncheon, then hands them scripts (co-written with Carlotta Corradi and Elisa Casseri) for a movie he’s titled Diamonds and already cast.

These opening scenes are Ozpetek’s framing device. Though he doesn’t mention it by name and flashes it onscreen for only a second, the director’s subject is a lookback at Sartoria Canova, a costume shop in Rome that clothed stage and screen productions in the 1970s. Owned by two sisters—the humorless Alberta and the emotional Gabriella—Oztepek’s reinvented shop is tasked by an Oscar-winning costume designer to create wardrobes for an 18th Century historical epic. The key dress will be worn by the female lead in the picture’s concluding scene, and must be a completely original and spectacular creation, This will become the work of the costume designer and the shop’s tailors, shoppers, seamstresses, cutters and drapers. Plus the cook (a winning Mara Venier) who keeps her dressmakers going through an all-night race-against-time to make the first shot of the following day’s shoot.

It is, to be sure, a fetching concept for what becomes an irresistible two and a half hour immersion in the art of movie costuming. All the ladies in Ozpetek’s marquee-heavy cast are adroitly intercut, with each actress given a spotlight scene or two. Luisa Renier nails the brittle Alberta and Jasmine Trinca has tightrope control as the troubled Gabriella. As the historical movie’s Oscar-winning costume designer, Bianca (Vanessa Scalera, vividly volatile) is a mile-a-minute whirlwind of demands. She may be channeling Danilo Donati, who won Oscars for costuming pictures by Fellini and Franco Zeffereili in the era. Playing ‘Oscar,’ the director, Stephano Accorsi definitely channels every bad-tempered helmer on a movie lot.

Oztepek dedicates his picture to departed legends Mariangela Metato, Verna Lisi and Monica Vitti (the latter starring in her own upcoming retrospective at Lincoln Center). But the off-camera star of Diamonds is, of course, its costume designer, Stephano Ciammatti. The specs for his eventual creation demand something “corporeal, luminescent, a rainfall, a river, armor for the heart, a cascade of molten lava.” In short, a dress you will gasp over. The final Diamonds dress, without question, could halt the annual Met Gala (where the unimaginable reigns supreme) in its tracks. You’ll have to see this movie to believe it. As the ads used to say, “A Diamond is Forever,” and Ozpetek has just created one for the books.

The Time It Takes: Francesca Comencini: 2024: Italy/France: 110 minutes

Like Ozpetek, Ms. Comencini has been absent from Open Roads for eight years. But she’s found a captivating way to reintroduce herself to new audiences—rolling out a tender but frank and occasionally painful father/daughter portrait of growing up with her movie director dad, Luigi Comencini (1916-2007). Her father was an outwardly confident, commercially successful A-list helmer who directed mid-century stars like Gina Lollobrigida and Vittorio De Sica, Claudia Cardinale and Alberto Sordi with equal aplomb. The elder Comencini admired silent masters Charlie Chaplin and G.W. Pabst, and mostly made audience-friendly pictures. His favorite was a 1972 feature (and mini-series) based on the dark Italian children’s classic Pinocchio.

This is where The Time It Takes begins, with Luigi (Fabrizio Gifuni, a gravely handsome blend of devoted parent and stern authoritarian), shepherding his young daughter Francesca (Anna Mangiocavallo, adorable) through The Adventures of Pinocchio, with its fearful puppets, shark and whale. The father/daughter bond is close—they hold hands and hop down the block together. But on location for the movie’s production, Francesca witnesses her father raging at the assistant director and then yelling at her to get out of a scene she’s unknowingly wandered into. Ms. Comencini weaves this leisurely, detailed introduction to an uneasy childhood (her mother and three siblings are never seen or referenced) with a domineering father who we’ll come to understand is barely controlling his own career frustrations and failures.

And so Francesca grows up (now played by a moody, downcast Romana Maggiora Vergano) into a rebellious 70’s student besotted with peace marches, Neil Young songs, her first longhaired lover, and a serious drug problem she denies but can’t conceal from ever-present dad. (Italian cinema fans will remember Francesca Comencini dealt with her addictions in her 1984 directorial debut, Pianoforte.) When Italy’s Christian Democrat leader Aldo Moro is kidnapped and murdered by Red Brigade terrorists in ‘78, the devastated director pauses his career and orders his daughter to accompany him to Paris. “What will we do?” asks the unstable young woman. “We’ll go to the cinema,” replies dad.

The Time It Takes is the latest arresting example of how family dynasties in the movie industry are formed and supported. Francesca’s sister, Paola, was this biopic’s production designer, and among its producers is master director Marco Bellocchio. Dynasties have enduring appeal to aging art cinema audiences, and Comencini’s latest easily earns its Opening Night spotlight in this edition of Open Roads. With a distributor and six Donatello Award nominations in place, plus Ms. Vergano’s win as best actress in the Venice Film Festival, The Time It Takes gives Luigi Comencini an extra victory lap as a top director who told compelling stories for adults…as well as a good dad who made magic for his kid.

The Great Ambition: Andrea Segre: 2024: Italy, Belgium, Bulgaria: 123 minutes

As you’ve noted, both Diamonds and The Time It Takes explore Italian cultural history in its turbulent 1970s. The country’s charged political landscape in that era has ignited even more provocative cinema. Italy’s premiere filmmaker digging deep into his country’s tangled relationship with the Communist Party has been Marco Bellocchio. In 2003 his Good Morning, Night took the point of view of a female Red Brigade revolutionary who helped block the motorcade of the Christian Democrat party leader, Aldo Moro, killing all of his security detail and kidnapping Moro. Bellocchio followed this with his five hour Exterior Night (New York Film Festival, 2022), in which he suggests a traitor somewhere in Moro’s cabinet may have helped engineer the abduction and is letting him suffer, while Moro’s frantic staff implore Pope Paul VI to intervene and secure his release. (Moro was acted by no less than Fabrizio Gifune, the dad movie maker above.)

Now Andrea Segre tackles this national crisis from yet another fascinating perspective—that of the secretary-general of the Italian Communist Party, Enrico Berlinguer. A devoted husband and father of three teen daughters and a son, Berlingeur’s singular ambition for over a decade was trying to forge a middle ground between democracy and radical extremism, adopting Marxism but rejecting fascism and Soviet meddling. He came close. At the height of Berlinguer’s striving for a coalition government he’d not succeed in forming, one out of three Italians (including Fellini) voted for Communism.

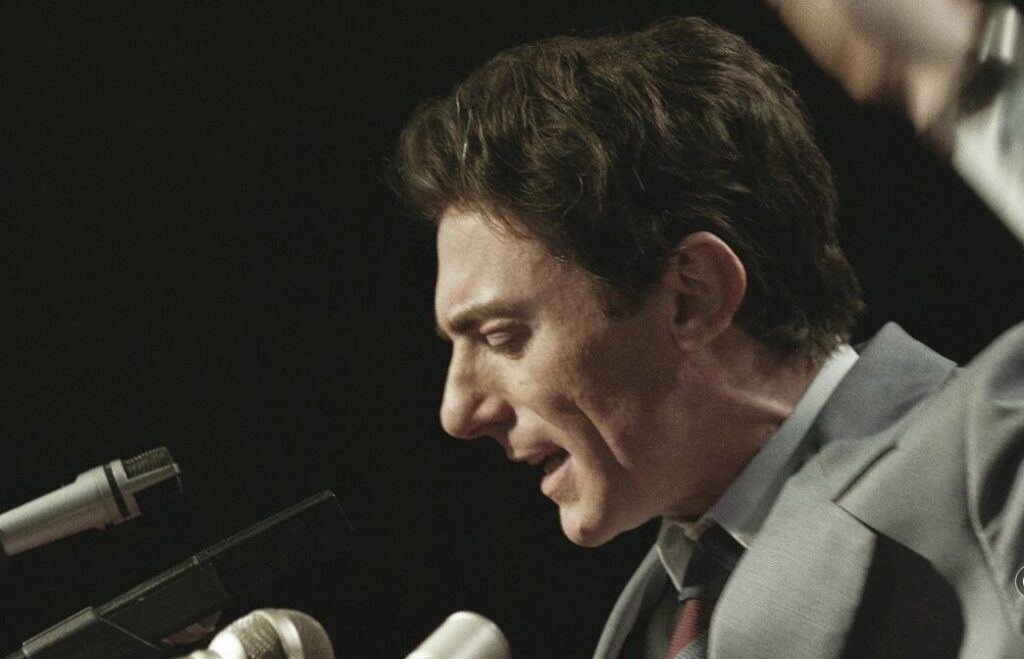

Segre mounts a riveting drama aided by select documentary footage that validates her narrative, co-written with Marco Pettenello. She studied dramas like Gus Van Sant’s Milk (Sean Penn as gay activist Harvey Milk) and Spike Lee’s Malcolm X (Denzel Washington as the Harlem activist). Segre knew she needed an actor persuasive enough to have won several million Italian hearts of all ages. She hit the jackpot with Elio Germano, who has the charismatic bearing of a certain U.S. politician now running for NYC mayor, and the crowd-rousing punch and drive of a young Al Pacino. Germano’s passion is unquenchable and he’s always likeable, even when he’s loathing capitalism and all the inequities built into it. A lot of The Great Ambition is taken up with the zealous Berlinguer rallying the Italian population, his cabinet and especially his children and wife, Litizia (a fine Elena Rabonovich), along with several face-to-face, give-and-take meetings with Moro (the eloquent Roberto Citran).

Segre keenly senses she’s got to leaven all the serious political diatribes with glimpses of humanity, and she does. There’s a continuing gag of dad searching for paper money he left bookmarking a copy of Rosa Luxemburg’s The Accumulation of Capital. He’s about to answer a query on his favorite Fellini movie when he narrowly escapes an assassination attempt on his own life in Bulgaria. Communist leaders in Moscow can’t get over that U.S. president Jimmy Carter is a peanut farmer. They brag to Berlinguer that cleaning women eat pickles in their affordable seats at the Bolshoi ballet. A teen daughter of the gutsy party leader tries out four-letter words to describe dad’s opponents. The music score of losonouncane stays subtle and melancholy, calling less attention to itself than his name. After Moro’s body is found in a car trunk in the center of Rome, the father carefully instructs his family never, ever to negotiate with terrorists if he’s taken, too (though it’s a stroke at a rally that will end his life in 1984). Like all great directors of historical drama, Segre senses it’s the details, the surprising anecdotes that viewers long for and remember.

In a 2025 season of change in which American political, economic, cultural and social history is being altered every waking day, The Great Ambition offers an unexpected hero for American audiences to root for, a salt-of-the-earth statesman nearly half a neighboring country’s people once cheered on. It’s a curious sensation to experience in a Manhattan movie theater these days and nights, and it may be one you never imagined could or would be so endearing.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 63rd New York Film Festival, Sept. 26-Oct. 13.

Regions: New York City