Rendez-Vous with French Cinema – March 5-15

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw salutes two leading ladies of cinema

You’ll forgive your 81-year-old Manhattan moviegoer if his first three reviews below putter about, pausing to stare at the pleasure of spending a few more evenings in the dark with two of France’s leading ladies. Simply put, these women were two of this viewer’s youthful heartthrobs. They were so, so French!

Anouk Aimee, now 87, began making films in 1947; Catherine Deneuve, now 76, made her screen debut a decade later. Both women have long been in full command of their craft; both have anchored many of Rendez-Vous’ quarter century of festivals, now sponsored by Film at Lincoln Center and UniFrance. They are international treasures, each shown to stunning advantage in two new movies-about-movies, with Deneuve getting a second marquee billing in a visceral family drama.

The Best Years of a Life; Claude Lelouch; France; 2019; 90 minutes

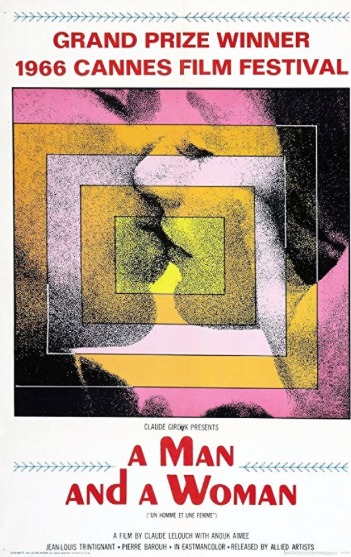

Victor Hugo’s line “The best years of a life are those yet to be lived” in the first seconds introduces us to Lelouch’s 49th film, his third exploration of Anne (Anouk Aimee) and Jean-Louis (Jean-Louis Trintignant). The first, A Man and a Woman, was a seminal French film of 1966, a picture that significantly helped to lure big city moviegoers away from Hollywood fare and into off-the-beaten-path ‘foreign cinema.’ Two Oscars for best screenplay and best foreign film broadened its appeal even more. So did the irresistible pairing of Aimee, playing a shy, studio script girl, against Trintignant’s devil-may-care race car driver. The film’s lush theme by Francis Lai was a breakout element, as was Lelouch’s blending of color exteriors with monochromatic black-and-white that framed their intimate couplings like museum prints.

Lelouch’s 1986 sequel, A Man and a Woman (20 Years Later), found the divorced Jean-Louis still pursuing Anne, who he refuses to commit to. She’s recently widowed, having become a film producer whose movies have consistently failed. Piloting his red Mustang though he now works for Lancia, Jean-Louis solidifies into a selfish, philandering rogue. Lelouch uses the same romantic theme music and swirling camerawork, but Anne won’t be swayed—she knows her lover will forever remain a skirt-chaser as well as a speed demon. Many viewers, mainstream as well as art house patrons, expected a happy ending and rejected the picture.

Now, in The Best Years of a Life, Jean-Louis is confined mostly to a wheelchair in an assisted living facility where he’s been placed by his cinematic scholar son, Antoine (Antoine Sire, again cast in the role he played as a child). The aged racer’s mind is still racing with poems and visions of women, mostly Anne as he knew her half a century ago. His mind is also crumbling—he’s in and out of lucidity, often with split-second variations.

Trintignant, now 89, came out of retirement for this assignment, and he may be capping a brilliant career—much as Jean-Pierre Leaud did in The Death of Louis XIV. Jean-Louis is kittenish and catty, polite and salty-mouthed—he keeps bidding his dutiful female attendant to sleep with him, and sets a wristwatch for an escape he’s planning at 4:00am. It’s odd to describe a male performance as bewitching, but Trintignant isn’t really looking for sympathy, recreation or companionship. Like Louis XIV, he’s patiently waiting to die…until Anne walks back into his life.

Anne’s driven her Citroen A2CV to see him, at the urging of Antoine. She’s moved to Normandy where she’s runs a modest fabric shop and stays close with her veterinarian daughter Francoise (Souad Amalou) and granddaughter Elena (Monica Bellucci). But this man and this woman’s first long conversation, out on a sunny lawn, is in many ways the film’s centerpiece, and it’s one of those minor cinematic landmarks you want to lower a bell jar over and preserve forever. For Jean-Louis begins to slowly recognize his old lover—it’s her casual pushback of her hair from her eyes that have always riveted audiences— and his eyes more than anything else tell you that the best years of his life could have been with her, and he’s let them slip away forever. When he ruefully admits “we’re faithful until we find better” and confesses to Anne that “it’s easier to seduce a thousand women, then to seduce the same woman a thousand times,” his eyes give away how much he regrets his words and perhaps how he lived his life.

You don’t need to have seen either Lelouch’s ’66 original or its ’86 sequel, because the director interweaves them here and in the scenes that follow.

His screenplay, co-written with Valerie Perrin, is immensely subtle and knowing. When Anne takes Jean-Louis out for a ride in her Citroen, the writers invent some playful, imagined interludes of outlandish behavior for both of them. They’re dream sequences, full of foolishness. For her part, Madame Aimee is still a ravishing beauty, just as she was last time she appeared on the same Rendez-Vous slate as Madame Deneuve, playing a World War II mother in Lelouch’s lavish (and totally overlooked) spectacle, What Love May Bring in 2011.

Was there ever a director so in love with cinema as Lelouch? After working with 16mm and 35mm film all of his career, he shot 30% of The Best Years of a Life on an iPhone. He’s shot 100% of his upcoming 50th film, La Vertu des Imponderables, a musical, the same way. Onward.

The Truth; Hirokazu Kore-eda; France/Japan, 2019; 106 minutes

One of the bravest performances ever by a screen actress playing a fading movie star was Charlotte Rampling’s 17-minute French short created by Didier Marcelo and aptly titled The End. It was shown in the 2012 edition of New Directors/New Films. Rampling, then in her mid-60s, settles down in her living room to watch an older film being televised. The picture is Viva la Vie!, directed by Claude Lelouch in 1984. Only the woman on screen isn’t Rampling, who made the picture when she was 38. In all of Charlotte’s scenes, she’s been digitally removed and replaced by a 20-something played by Liz Gareth.

Rampling storms into her producer’s office for an explanation. She’s told her movie is being shown with “the new Charlotte Rampling,” an actress more suited to an age of remakes, digital imagery and streaming. Furious, Rampling invades a film set where her “replacement” is acting away on another of Charlotte’s past pictures. Rampling throws a hissy fit while the director, producer and crew—all in their 20s— look on with sleepy, uncaring smiles. Exhausted and devastated, Rampling reels outside into the sun, where the camera closes in as pieces of her begin to slowly dissolve off the screen. Wow. Only an actress as fearless and as confident of her peerless artistry as Rampling would have taken such a role.

Much of that same feeling pervades Catherine Deneuve’s equally breathtaking and career-defining performance as film star Fabienne Banjeville in The Truth, the Opening Night selection of this festival. (It opens commercially March 20.) Like Bette Davis in The Star, even like Gloria Swanson forever ready for her close-up in Sunset Boulevard, Fabienne keeps adjusting the hard truths and secrets of her life that are clawing away at her legend. It’s a shrewd, calculating star turn—the meatiest role Denueve has had in a quarter century of Rendez-Vous festival appearances. For his followup to Shoplifters, writer/director Kore-eda has fashioned a barbed satire that drills deep into the hushed up realities of the movie biz as it was once lived. Sometimes it bites hard enough to draw blood.

Fabienne’s handsomely appointed metropolitan home is abuzz with activity as the actress greets her visiting family—her Manhattan based screenwriter daughter Lumir (Juliette Binoche), her TV actor, fresh-out-of-rehab son-in-law Hank (Ethan Hawke), her button-cute granddaughter Charlotte (Clementine Grenier). They’ve come to celebrate the publication of Fabienne’s memoir (“Le Verite”), but to Lumir the memoir instantly reads like fiction. (The actress claims a first printing of 100,000 copies; it’s actually half that.)

Lumir fills her copy with dozens of post-it notes marking all her mom’s false and fabricated memories…childhood years spent growing apart from a movie star who was perpetually on location. In the memoir, Fabienne claims she loved Lumir as Dorothy in a school production of The Wizard of Oz, but Lumir played the lion and her mother wasn’t there. For Fabienne, the work came first, last and always. “I’d sell my soul, but not my body, to the Devil for the right role,” she brags, but we learn half that statement’s a lie, too.

And the roles aren’t looking so good at 73. That’s the screen age of her character in a goofy science-fiction fantasy she’s been cast in, titled “Memories of My Mother.” The sets are rudimentary and the ever-smiling director doesn’t look old enough to vote. Fabienne’s role is this quirky: she plays the daughter, not the mother, of Manon (Manon Clavil), a doe-eyed young beauty whose terminal illness miraculously keeps her from aging. Manon gets to visit her aging daughter (Deneuve) every seven years, so Deneuve keeps growing older and older while Manon doesn’t age at all. Maybe this is why Fabienne’s having trouble remembering her lines.

Kore-eda keeps piling up Fabienne’s character defects, one on top of another. It starts with her lifetime personal assistant, who resigns when he discovers Fabienne didn’t give him even a mention in her memoir. We learn the Cesar award winner slept with a director to get the role that won her France’s most distinguished acting award, in a role that should have gone to another woman. You can decide if that’s Fabienne’s worst fault, but watch closely what she does when Hank, who annoys her no end, breaks his sobriety during a boozy dinner, drinking a glass of wine she’s poured him. And then she fills the struggling alcoholic’s glass a second time. Some mother-in-law.

The Truth never holds long enough on any of Fabienne’s pesky failings to bring down the generally buoyant mood surrounding Deneuve’s grand tour-de-force. Kore-eda adroitly interweaves the solemn clashes between Fabienne and Lumir with the more illusory movie dialogues between Deneuve’s aging daughter and Clavil’s perpetually young mother. These are The Truth’s artistic soul, as Kore-eda cleverly juxtapositions the illusions and truths of Fabienne’s personal and professional lives, and lets them spin and spit themselves out. The director maintains a relentlessly upbeat mood that somehow never drags down the proceedings.

Maybe that’s because Clavil, Binoche and Hawke—as well as a large supporting entourage of Fabienne’s extended family—all seem thrilled to surrender this movie to Catherine Deneuve. The big-screen drama and its rickety movie-in-a-movie Fabienne is stuck acting in are both hers, and Deneuve exults in both. There’s a telling moment when, being driven to the set, Fabienne spots the former home of Michele Morgan and sighs that so many legendary screen actresses all have or had first and last names starting with the same letter—Anouk Aimee, Danielle Darrieux, Greta Garbo, Simone Signoret. (She mentions Brigitte Bardot, then shrugs her off.) For a moment—just for that moment—Fabienne acknowledges a few of her past and present contemporaries.

Happy Birthday; Cedric Kahn; France/Belgium; 101 minutes

This is the festival’s second feature with Catherine Deneuve, and it starts virtually the same way as The Truth—with a large family arriving at a gorgeous country home to celebrate Granny’s birthday. Here Deneuve is cushioned into a marquee-topping support role—the happily married, busy bee elder who’ll welcome a son and daughter who are both volatile, unstable misfits. Unlike Kore-Eda’s cheerfully cynical family reunion, Cedric Kahn’s gathering of the clan is amusingly normal at the outset but grows steadily darker, then darker still, then black as pitch.

You will be relieved to know this birthday celebration doesn’t end like Parasite. Instead it’s a showcase for the never-ending talents of Emmanuelle Bercot, a Cesar-winning knockout in Maiwenn’s My King (critic’s choice, 2016 Rendez-Vous) and Vincent Macaigne, one of France’s hardest working actors, who actually starred in three films chosen for one Rendez-Vous festival. Bercot plays Deneuve’s jittery daughter who disappeared for three years into a bitter, failed relationship and may have been institutionalized. Macaigne plays her son who’s a Parisian train wreck of a pothead and drunk. As brother and sister, these two powerhouses are linked in unimaginable ways that Happy Birthday grimly peels away.

Deneuve doesn’t get a scene that rivals the fiercely escalating explosions of her children. She reverses fields from her dominance of The Truth, slipping back into an ensemble player we glimpse folding laundry, polishing glassware, cradling a daughter in her comforting arms, dancing along gamely with her family, and, on one occasion, holding pen poised to turn over the family home to a hovering real estate agent. Why? So her scheming, unbalanced daughter can invest her $200,000 share of the proceeds in a vegan restaurant in Portugal.

No wonder Deneuve frets with supine grace through one disastrous family dustup after another, graciously yielding the screen to her younger, battling contemporaries. Bercot and Macaigne continue their growing stardom with resounding, truly scary performances in this unruly, dysfunctional family. They earn the red carpet in Happy Birthday, start to finish. But every red foot of that red carpet still belongs to Deneuve in The Truth.

Proxima; Alice Winocour; France/Germany, 2019; 107 minutes

Deneuve’s Fabienne may have flounced off to exotic locations for movie shoots, leaving her daughter in the care of a knockabout dad, but she didn’t journey to Mars for a year. That’s the jolting news facing 10-year-old Stella (Zelie Boulant) an appealing Cologne youngster who’s coping with dyslexia as well as a recently separated mother and father. Her mom Sarah (Eve Green) has been suddenly plucked from the European Space Agency’s astronaut program; she’s a last minute substitution to a Russian/American/French crew chosen for a solid year’s training, which will then begin a second year’s travel in space, voyaging to and from Mars.

Alice Winocour’s Proxima, which takes its name from Proxima Centauri, the sun’s nearest neighbor, wants to be an astronaut movie with a heart as big as the universe. Its premise is a variation on a storytelling concept that’s almost as old as our solar system—a scientist’s dream assignment comes true, and triggers trauma for her child who’s going to be mostly separated from her mother for what seems an eternity. Everything in this movie hinges on how persuasive Eve and Zelie are at keeping you rooting for both.

Winocour and her co-screenwriter Jean Stephane-Bron craftily pile up a stack of obstacles against Sarah. Her American captain is a tedious Texan (Matt Dillon, aging nicely) who thinks women should remain stay-at-home moms like his wife. Her Russian counterpart is stand-offish, while their Soviet crew trainer is aghast whenever Sarah is distracted by thoughts of her daughter, or, worse, when the kid appears at the training facility. On top of that, the ESA assigns a stern psychologist, Wendy (Toni Erdmann’s Sandra Huller) to flank young Stella on her visits to mom.

The only asset—and it’s a vital one—that Winocour provides Sarah with is a cooperative husband she and Stella live apart from. Thoma (Lars Eldinger, subdued and effective), who’s conveniently an astrophysicist also in the space program, becomes the parent-of-record who’ll get Stella to and from school, feed her cat, help her with the math she’ll struggle with, and dry her eyes every night.

Like Diane Kruger in Winocour’s edgy thriller, Disorder (critic’s choice, 2016 Rendez-Vous), Eve Green is a hardwired, hardbodied choice. The director has called Green “a mutant,” and that’s part of her authenticity as she maneuvers artificial limbs and undergoes killer training exercises in centrifuges and in simulated underwater rescues. Green’s steely gaze melts the instant she’s with her daughter, and Miss Boulant (one of 300 girls Winocour auditioned) is sublime—turning vulnerability into resolve and ultimately, her mother’s strength. These are three-handkerchief performances.

Proxima also gets high marks for Winocour’s all-location filming in the ESA in Darmstadt which monitors international space missions, at Star City (near Moscow), Russia’s astronaut training center, and at the Soyuz launch site in Kazakhstant. The director cuts crisply and her music score by Ryuichi Sakamoto underscores the dramatics without overwhelming the principals. It’s a crowd-pleaser of a movie-movie that often morphs into a docudrama. Over the closing credits, Winocour shrewdly includes a gallery of news photos saluting real life female astronauts, posed with their proud daughters and sons. It’s the perfect closure, demonstrating how women worldwide have excelled as both astronauts and moms, off the big screen and now on it.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in New Directors/New Films March 25-April 5 at Lincoln Center and at The Museum of Modern Art.

Regions: France