NYFF 2015: Filmmaker in Residence Athina Rachel Tsangari

Staff writer Dana Knight discusses past, present and future with Athina Rachel Tsangari.

This year’s New York Film Festival Filmmaker in Residence is the acclaimed Greek director, producer, and actress Athina Rachel Tsangari. Dana Knight sat down with Tsangari for The Independent at the Sarajevo Film Festival 2015, immediately after her latest film, Chevalier, premiered at Locarno 2015. Tsangari curiously begins the conversation as Knight introduces herself, and the publication.

Athina Rachel Tsangari: The Independent Film Magazine? It still exists?

Dana Knight: Yes, are you familiar with it? It’s an old publication, it goes back to 1978, the longest running publication about independent film in the United States. It’s not in print anymore though, it’s digital now.

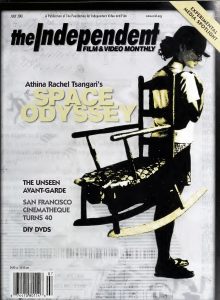

Tsangari: A long time ago, my first feature film The Slow Business of Going was on the cover of The Independent Film & Video Monthly. This was back in 2001. And I know the former executive director of this magazine, Elizabeth Peters. I’m so glad to hear this magazine still exists!

[The article was published in the July 2001 publication and covered the creation of Tsangari’s latest feature film. The article, Space Odyssey: All Over the Map with Athina Rachel Tsangari and The Slow Business of Going by Spencer Parsons can be read in full in our online archive, which is currently single pdf’s by year. For the isolated article, visit our Facebook page. In it, Tsangari spoke of her interest in honoring cinema, albeit with poor timing, a parallel that she discussed regarding her current work:

“We started the film in the centennial of cinema,” says Tsangari, “so we thought it was an appropriate time to pay homage to the pay beast. But now that we’ve just finished, the 100th birthday isn’t really news anymore. We kind of missed the deadline.”]

DK: Now, about your new film, Chevalier. I saw it twice, first time in Locarno when it premiered and the second time here in Sarajevo.

Tsangari: Was it different the second time?

DK: Yes, I picked up on details that I missed out on a first viewing. It’s such a rich text with many subtleties and my question actually refers to this: I would say that while the obvious themes of the film are power relations, politics, the crisis of masculinity, it seemed to me that the film talks a lot about cinema itself, and art. Would you agree with this and how did you handle subtext in this film?

Tsangari: As a filmmaker in this century, I like the idea of working with something that is literal. There is a literal situation here: these guys who are on a fishing trip get bored and the ship breaks down and they play a game to fill their time. So I was interested in this situation: what happens when you’re stuck with people who are not necessarily your best friends and somehow you have to start measuring up yourself. Even if they did not play that game. Being in a confined environment you have to constantly evaluate who you are in relation to the others, even if this is just through the glasses that you wear, or the way you eat, or by how many books you’ve read in your life, or by how much money you make. That’s the literal situation. But what I’m interested in, because I’m making cinema and not writing a book, is the performance of the body, and this is something I’ve been doing since The Slow Business of Going.

DK: What interests you the most about the body in cinema?

Tsangari: I’m interested in the ways in which the body expresses itself, rebels against itself, demonstrates itself, makes fun of itself and becomes vulnerable and permeable. In this case it was male bodies. In The Capsule, which was my previous film, it was female bodies. I’m interested in how these bodies, these little creatures are very vulnerable and very sensitive and very tender and very tough at the same time. In every scene there was dialogue and apart from the dialogue you watch these bodies. And these bodies were relating to each other in subtle ways but also in big ways, like the lip-syncing scene or the fight that those guys have, or the physical exercises that they do, even the way they sit is a performance. And that’s actually the most difficult thing: how to sit. Half of the history of cinema is people around a table, talking. How do you shoot that? How do you choreograph what seems like talking mouths. How do you re-approach that? And because I haven’t made a film before that was so concentrated on speech and the human face, that was my challenge. So maybe what you picked up on was my agony on how to do the decoupage of that and how to choreograph it. We rehearsed for a month for a theatre performance and then we filmed that performance.

DK: It must have been a very intense process…

Tsangari: It was. I was very lucky to have actors who were very different from each other: one of them is a film director, the other is the biggest pop star in Greece, the actor who plays the doctor is a renowned theatre actor who has never been in a movie. Vangelis Mourikis was in my previous film, Attenberg, I was very familiar with him, but not at all with the others. So the challenge for all of us was merging these body languages and these speech patterns into something that created a symphony of gestures and words.

DK: How did you work at the script stage? And have you later modified the characters to match the personality of the actors?

Tsangari: The script that I used, and that Efthymis Filippou and I co-wrote, had the basic sketches of these characters but they became much more precise after the casting. I knew the archetypes of the characters and in a way I did not want to be too psychological with them or give any sort of background or backstory. I knew the basic archetypes that came from screwball comedy and buddy movies. And then I cast actors for their personality, to bring the personality of the actors into the characters so that they enrich them and make them their own. So actually a lot of the script changed, they came up with their own contest that they suggested. Half of the stuff we had in the script did not work so well in the rehearsal. So I had each of them suggest five contests. Then we all voted and we chose the most interesting.

DK: Do you think it was a bit difficult for the actors to explore and challenge what it means to be a man?

Tsangari: One reason why they were cast is because none of them fits the stereotype of the “macho male.” But judging from the few screenings that we’ve had, I think some men feel very uncomfortable with this film and they hate it. It’s like: “We’re not like that and who are you, a woman, judging us in this way?” But it was such a great collaboration, none of the actors felt uncomfortable. There was so much enthusiasm doing the contests with each other, having this undercurrent competition going on. It was liberating for all of them to be doing stuff that they know they are doing in privacy. And the idea of deconstructing and subverting some cliches became more and more interesting. Women talk about food, men don’t and to have this kind of Western show-off between two men who talk about what kind of dishes they cook it was funny and those were actually their recipes! The actor Sakis Rouvas is a great cook and a spear fisherman. And the other guy is very proud of this salad that he once made. So this became a scene which literally was about food but also about both of them measuring their penises through the dishes that they make.

DK: I remember someone remarked at the press conference in Locarno that these men remind him of the women in Desperate Housewives! I would take that idea even further and make the risqué statement that, despite an all male cast and quasi-absence of female characters (except off-screen, on the phone), Chevalier almost comes across as a feminist film since it shows men in situations usually associated with women in cinema: stuck in a confined space as opposed to conquering the great outdoors. Their presentation as vulnerable, insecure subjects or as the object of the gaze, in the lip-syncing scene for instance, is also relevant in this respect.

Tsangari: I set out to make a film about human nature. To me it was simpler to make it with men only so that it doesn’t become about the relationship between genders, which always confuses. I was interested in how the same species would fight it out with itself, with the same tools. And how masculinity and femininity would oscillate in each one of them, because we have feminine and masculine in all of us. So I think it would be quite similar if I worked with a female cast. The Capsule was similar, it’s just a different genre. That was a horror fantasy, this one is a buddy movie. The next one, in which I will do exactly the same thing, will be an action film. My own kind of action, with my very limited resources but with a female action hero, that’s what I want to explore in my next film.

NYFF will host a discussion with Tsangari about her past and present work on Wednesday, October 7 at 7.45pm at the Film Center Amphitheater. The event is free to the public.

Regions: Europe