Rendez-Vous with French Cinema 2016 – Critic’s Choice

Kurt Brokaw views all 21 features at the 21st annual festival which runs March 3rd to 13th

Valley of Love

(Guillaume Nicloux. 2015. France/Belgium. 92 min.)

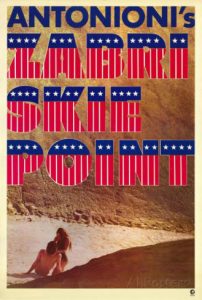

In 1970 your senior film critic was in full Don Draper mode, playing advertising creative director of MGM movies. One assignment was to create the ad campaign for Michelangelo Antonioni’s first American film, Zabriskie Point, part of which is set in Death Valley. Milton Glaser was hired as chief designer and we flew to Rome to view the rough cut with Antonioni, Monica Vitti, and co-screenwriter Clare Peploe, who’d become Antonioni’s muse and companion.

Zabriskie Point was a counterculture sucker punch of a movie, a disaster of unimaginable magnitude, ugly, witless and condescending. Nonetheless, Glaser worked up a slew of fabulous posters—American flags set aflame by hippie protestors, closeups of police in ominous gas masks, custom-crafted peace symbols hanging between sweating breasts, et.al. The one-sheet exploratory comps certainly captured the movie and the era.

We flew back to Rome and laid all this work at Antonioni’s feet. He stared at it and shook his head, “No no no, that is not my movie.” Meekly your writer asked what he felt his movie was. Antonioni said, “Do you recall the scene where Daria and Mark (the young iconoclasts who meet in Death Valley) make love in the sand?” Yes, for a minute or so of your 112 minute hate letter to America, ventured the writer. “That’s my movie,” said the director firmly, “And that’s your advertising campaign.” So it was, and is. Just another love story set in the valley of love. Truth in advertising.

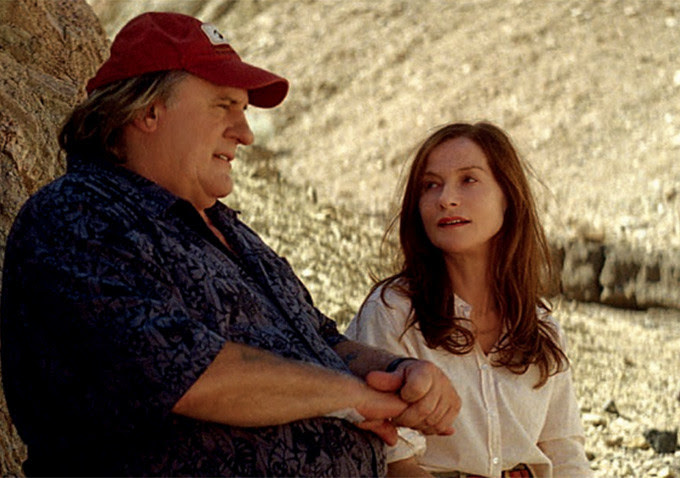

That rueful memory came to mind watching a far superior film (and the Opening Night selection of the 21st edition of Rendez-Vous presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and UniFrance). In Valley of Love, Gerard Depardieu and Isabelle Huppert, two of France’s grandest cinematic icons, more or less play themselves as a divorced couple reuniting at the request of their grown son, Michael, a recent suicide in San Francisco where he lived with another man. Michael reached out to them in a letter found at his death urging them to come to seven sites in Death Valley, including Mosaic Canyon, where he promises to re-appear before each of them on November 12, 2014.

Depardieu, now uncomfortably obese (in real life) and suffering with bladder cancer in the film, joins his former spouse (Huppert), who’s truly grieving over their son’s death and is about to leave her current husband. The other tourists at the resort hotel are as obnoxious and empty-headed as the tourists in Antonioni’s movie almost half a century ago.

Director Guillaume Nicloux wants us to believe this is actually happening, and he creates separate scenes with Depardieu and Huppert that convince each of them the boy is indeed alive. Visual evidence is left with them to share with each other and with us. The setup is different from Journey to the Shore, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s recent reincarnation drama, in which a dead husband who’d been devoured by crabs walks back into his wife’s life, none the worse for wear, and escorts her on a journey back through the high and low points of their married years together. Here we never see the deceased son.

(Yet a third back-from-the-grave chestnut, the 1943 Heaven Can Wait, also shown with Journey to the Shore at last fall’s New York Film Festival, posits the theory that playboy Don Ameche, an unfaithful rogue who marries Gene Tierney and dies of exhaustion at 70 after dallying with a showgirl, gets a pass out of hell but not necessarily a lift into heaven.)

Depardieu and Huppert have considerable time in Valley of Love to ponder their lost lives and former love for each other. Perhaps that love will be rekindled by this presumed re-appearance of their son. Maybe the grown boy engineered it all before he killed himself, as a final desperate bid to bring mom and dad back together.

In lesser hands, this would be an ungainly (not to mention ungodly) premise. But Depardieu and Huppert are revisiting their swankier styles way, way back in 1980 in Loulou, in which he was a handsome, long-haired, thugish lothario and she was making time in an ad agency. Their love scenes— trim, free-flowing, jauntily playful—weren’t all that different from Daria and Mark discovering each other in the scalding sands of Zabriskie Point.

Here, 35 years later, Depardieu and Huppert contemplate their past, present and future beside a deserted nighttime swimming pool in Death Valley. He’s playing the absent movie star dad with all his grizzled customary authority, and Huppert is again demonstrating why she’s the master architect of suffering-with-a-pedigree, her screen specialty. These are legends—both seem to be getting slimmer and heavier each time we see them—who we’d line up to watch reading a telephone directory together.

What they’ll find in their time remaining is unclear. But, as the trailer for Zabriskie Point once-upon-a-time beckoned, “How you get there depends on where you’re at.”

Valley of Love shows Thurs, March 3 at 6pm at the Walter Reade theater in Lincoln Center.

Disorder

(Alice Winocaur. 2015. France/Belgium. 101 min.)

Alice Winocaur’s second film is as sleekly stealth and as coolly observed a thriller as Katherine Bigelow’s second film, the 1987 Near Dark. Bigelow was inventing nasty new twists on a traveling family of vampires. Winocaur leads you into the mostly uncharted territory of the privileged and guarded elite, here a mother and son, suddenly under siege by rogue kidnappers and masked terrorists.

Vincent (Matthias Schoenaerts) is a big-muscled, heavily tattooed member of the French Special Forces, on leave. Like other war-shocked veterans who fought in Afghanistan, he’s heavily medicated and subject to PTSD attacks at any time; the military authorities are doubtful about his return to combat. So Vincent takes a job guarding a luxe evening party at a coastal estate known as ‘Maryland,’ hosted by a Lebanese businessman with a German wife, Jessie (Diane Kruger) and their young son.

As in the Holocaust drama Son of Saul, writer/director Winocaur elects to hold very tight on the lead character, as Vincent and the camera prowl this cushy gathering. What this tightly wired and heavily armed guard silently observes is that the host is involved in illegal arms smuggling and is mired in financial debt. All Jessie knows is that her husband is always traveling and she’s in charge of running the household and its staff — she’s beautiful, smart, imperious and totally dismissive of the hired help which includes Vincent. A perfectly turned out member of the one-percent.

You’ll wonder where all this will take us, but Winocaur is in no hurry to push the plot forward. She lets us luxuriate in a fashion-mag look at life-at-the-top, as she subtly implants an undertone of instability and threat that’s underscored by the huge tat ‘CHAOS’ inked into Vincent’s meaty arm. We’re uncomfortably aware something is gravely amiss in this household. The electronic score by Gesaffelstein lays down its own quietly unnerving buzz.

When Jessica’s husband is again summoned to foreign lands, Vincent is hired as personal security for his wife and son. She elects a day on the beach with her son, and Vincent, driving, is immediately aware of the car following them. The car doesn’t just follow, it plows into them — it’s either a kidnapping or planned murder, and it’s as frightening a shock-and-awe attack as anything Vincent has experienced in combat.

He takes out the hooded assassins, and gets Jessica and the boy unharmed back to their mansion…where she learns her husband has been arrested and is being held in Switzerland. On top of that, the house has been tossed and the servants are missing. Reluctant to involve the police, Jessie makes a decision, for the first time her steel-trap thinking is faltering, to depend on Vincent to protect her and the child. And then the killers move in.

We’ve watched this kind of setup before — the armed drunks rampaging the country home of Dustin Hoffman and Susan George in Straw Dogs, Robert De Niro’s crazy ex-con trapping Nick Nolte and Jessica Lange on the houseboat in Cape Fear, even Bigelow’s loony family of bloodsuckers invading a country saloon in Near Dark. It takes a Peckinpah, Scorsese or Bigelow who knows how to pull out all the stops to make this kind of bloodbath work, and Winocaur is equal to the occasion.

Schoenaerts is the perfect killing machine — he’s standing in for the dad and husband who’s the cause of all the carnage that erupts. And Kruger is aces, delivering a telling portrayal of a trophy wife whose toned layers are peeling away by the second. Disorder is very much in order as this Rendez-vous’ signature thriller.

Disorder shows Sat., March 5th at 6:30pm and Mon., March 7th at 4:00pm.

Summertime

(Catherine Corsini. 2015. France/Belgium. 105 min.)

Think Carol on the farm. Catherine Corsini’s bucolic romance is mostly set on a farm near Limoges. It’s 1971, and lesbian love was far more advanced on the artistic front here in America than in France. Ann Bannon had published her six seminal novels on the life and loves of the Wisconsin-moved-to-Greenwich-Village icon, Beebo Brinker, Marijane Meaker was transitioning from paperback originals to the mainstream Little, Brown publisher with novels like Shockproof Sydney Skate and Valerie Taylor was deep into her Erika Frohmann tetrology of the life journey of a lesbian concentration camp survivor, having thankfully left behind novels like Hired Girl, in which sex-on-the-farm had to be between man and woman.

But in Paris, even in pioneering women’s liberation groups, Carole, the feisty leader portrayed by Cécile de France at 40, still had a boyfriend. And up in the sticks, at the farm, the 25-year-old daughter Delphine (Izia Higelin) was driving a tractor, milking the cows and politely shooing off a male beau dying to take her hand in marriage. The conventional boundaries were holding. That’s when the stocky Delphine, who’s shown heaving bales of hay as handily as any worker, migrates unexpectedly to Paris to sample city life.

And director Corsini, whose 2001 drama Replay told the achingly frustrating tale of two childhood pals (Emmanuelle Béart and Pascale Bussières) who circle each other lovingly through separate lives without ever quite finding each other, has clearer sailing in what she can show-and-tell. Maybe Corsini was drawn to this story as a “never-again” tale of unrequited love in a bygone era.

For Delphine and Carole fall madly, deeply in love. Still, when her father suffers a stroke, she returns to the farm to handle the daily workload she’s left behind. And Carole comes to visit, and then moves in, and at last we’ve got sheep in the meadow and girls in the corn. It all comes to a skidding halt when the mother (uncannily acted by Noémie Lvovsky, herself a director of repute) finds the two coiled in bed. Will she dismiss the sinning Parisienne? Will Delphine follow her love? Corsini has several surprising reveals in this movie, actually more than several, which are both intelligent and true to their French heritage and the social realities of their day.

Higelin and de France are both comfortable and believable as lovers more than a decade apart as well as women linked to, even wedded to, their vastly different rural and metropolitan environments. In varied ways, Summertime is another variation on the themes of Replay, given a bolder visual palette. Neither of Corsini’s movies have the thrilling close of Carol, but then Carol was replicating the first happy ending in a lesbian novel published by a mainstream imprint (Bantam in 1953) in the 20th century.

Summertime shows Tues., March 8th at 9:15pm and Sat., March 12th at 4:30 pm.

My King

(Maïwenn. 2015. France. 128 min.)

Is it favoritism on the critic’s part that three of his four review choices in this fest were directed by women? Not at all. Women mostly made the best films chosen for inclusion, as well as others not saluted here (Valeria Bruni Tedeschi’s Three Sisters, Julie Delpy’s Lolo, Emmanuelle Bercot’s Standing Tall, Danielle Arbid’s Parisienne). If you’re looking for a woman’s footprint in your cinematic selections for spring 2016, Rendez-Vous with French Cinema offers you a prime checklist.

Maiwenn’s My King is the most quintessentially French movie-movie of the lot. It pairs Emmanuelle Bercot (in a performance that won her the Best Actress Award at Cannes) and Vincent Cassel as a mismatched but much more endearing Parisian couple than Julie Delpy and Dany Boon attempt in Lolo. Tony (Bercot) is a frazzled lawyer slowly and painfully being rehabbed from knee surgery following a ski accident; her convoluted life — unmarried, then married, then unmarried, with the always disruptive Giorgio (Cassel) is told in a ten-year flashback.

What we see in detail is his perpetual adultery, alcoholism, drug addiction and non-stop manipulation of people, places, and things. And yet through it all there is his strangely winning (and desperate) need for a woman who holds onto him far longer than she should, and then finds she really can’t let him go.

He’s a French “Mad Man,” except Jon Hamm’s ad guy was rarely funny and full of self-pity. Cassel’s a Jaguar-driving restaurateur (though we only remember him there once in an amusing sex scene on a kitchen counter, and again in another restaurant setting where he imitates a waiter flawlessly, fooling everyone). He’s a high-functioning drunk and clown, a totally different kind of skirt-chaser.

Soon after marrying Tony, he moves across the street, saying she needs more room (and supposed independence) while he repairs his romance with the high-fashion model Agnes (played by Chrystele Saint-Louis Augustin in dazzling haute couture). Agnes gets lugged along through the movie like an 800-pound gorilla in the relationship. When Tony wanders into Giorgio’s pad one morning and finds yet another statuesque sweetie asleep in his bed, Giorgio denies all (“I don’t know who she is!”) and works that are-you-going-to-believe-me-or-your-lying-eyes routine so smoothly, it all but befuddles Tony.

Make no mistake, Cassel has more boyishly likable chops up on the big screen than Peter O’Toole ever displayed in his prime. The picture is buoyed by both Cassel and Bercot’s ferocious and tireless commitments to their characters and to each other. Tony drinks too much and not well, and Giorgio often plays scenes with the slightly incoherent effects of a lazy drug habit. When these abuses kick in, the couple unleash their repressed anger at each other with a fury that leaves your laughter in mid-air, frozen. Together they’ve created an exhaustively dysfunctional marriage with a superior French sensibility that’s miles ahead of American rom-coms.

“You can’t choose the people you love,” director Maïwenn has said in interviews. She also maintains she doesn’t want to send out any messages in this film, but her preceding statement is easily the film’s clearest message. The good news is we can choose the movies we love.

My King shows Wed., March 9th at 6:30pm and Thurs., March 10th at 9:45pm.

This concludes critic’s choices. Next up: Brokaw covers the 45th edition of New Directors/New Films, March 16-27 at Lincoln Center and the Museum of Modern Art.