New York Film Festival Sept. 20-Oct. 8, 2021

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw greets a robust Fall season on Lincoln Center’s big screens

In 1954, social protocols in a big single-screen theater were a lot simpler. At the Ritz in Indianapolis, a neighborhood showplace where this author worked part-time in high school, the main job of the ushers was making sure all patrons—especially dating teens—kept both feet on the floor at all times. This kid’s duties beside changing the marquee and popping the popcorn included patrolling the aisles with a flashlight.

During its glorious return to in-person viewing of the New York Film Festival over three weeks in Manhattan, dutiful staff again discreetly walked the aisles of the Walter Reade Theater during screenings. They were making sure all patrons had noses as well as mouths securely masked up. (No flashlights were used.) Neither food nor drink was permitted in the auditorium. All press and industry had photo badges starred with proof of vaccination. The theater was cleared and deep-cleaned after each of 38 Main Slate showings. Some critics nearly wept with pleasure at finally being able to view movies, safely and beautifully, on a screen 19 feet high and 35 feet wide. Film at Lincoln Center’s extensive protocols were welcome frosting on the cake.

This festival also welcomed its fourth director in 59 years, Eugene Hernandez, a quintessential New Yorker who still lives in Hell’s Kitchen and joined FLC in 2010, heading up digital strategy. He’s a veteran journalist who co-founded IndieWire in 1996 and has written for major online and print publications including The Independent.

The festivals’ main slate of 38 features came from 31 countries, and had as headliners Joel Coen’s severe and serious treatment of The Tragedy of Macbeth; Jane Campion’s homoerotic contemplations on a 1920s Montana ranch, The Power of the Dog; and Pedro Almodovar’s twisty and unpredictable Parallel Mothers. These were the opening night, centerpiece, and closing night selections. Dozens of revivals, retrospectives, avant-garde presentations and 34 shorts filled a robust schedule in three theaters on the Lincoln Center campus, plus over a dozen free talks and panel discussions ranging from the making to Steve McQueen’s Small Axe and Garrett Bradley’s Time to rethinking world cinema and examining films outside the canon.

The festival added Partner Venues like the Maysles Documentary Center in Harlem, Anthology Film Archives in the East Village, plus cinemas in Brooklyn and Pleasantville that showed fest selections. Corporate partners like Compari, Citi, Turner Classic Movies and MUBI pitched in to underwrite events from an Amos Vogel Centenary Retrospective to Maggie Glylenhaal’s The Lost Daughter. A volunteer staff of over 200 made sure patrons found their way through a daily maze of special events and theater operations.

The shadow of omnipresent streaming, and its impact on not just this theatrical celebration but all future festivals, hung heavy over many conversations. Director Joel Coen offered an uncommon perspective in a Q&A following The Tragedy of Macbeth, whose distributor is Netflix. He reflected back on the 1980s and 90s, when he and his brother Ethan’s career startups were building theatrical followings through NYFF showings of Blood Simple and Miller’s Crossing. At the same time they grew a strong “secondary market” of collectors who bought VHS tapes of Coen Brothers’ movies at the Blockbuster Videos of the world. The home viewing market, which today is the primary focus of distributors like Netflix, Apple and Amazon, was always a key component to countless viewers who kept their VCR’s in good working order. It’s still a market: Ebay currently lists over one million VHS tapes for sale.

Surely the most remarkable pushback against streaming to emerge from this festival was the unprecedented announcement that Memoria, the Tilda Swinton entry directed by Thailand’s Apichatpong Weeresethakul, will only ever be available in cinemas, “moving from city to city, theater to theater, week by week, playing in front of only one solitary audience at any given time.” The drama, based on the director’s own mild experiences with a sleep disorder called Exploding Head Syndrome, finds Swinton visiting Bogata and hearing loud THUMPS and BANGS! wherever she walks. The director equates this human condition with “Tired Mountain Syndrome,” which occurs when mountains are disrupted by too many underground detonations. In the Walter Reade Theater and Alice Tully Hall’s highly attuned sound systems, the BANGS! sounded like M80 fireworks going off just down the row, setting off car alarms all over Bogata neighborhoods. It’s a uniquely theatrical experience that most home systems can’t ever hope to match, and won’t. Kudos to Memoria distributor, Neon.

Here are critic’s choices on three features and two shorts:

Titane: Julia Ducournau: France: 2021: 108 minutes

In major film festivals, traditional horror films as well as untraditional horror films are honored and shown. The most recent traditional fright night celebrated with glee in The Independent was Marco Dutra/Juliana Rojas’ Good Manners (New Directors/New Films, 2018), about a Brazilian werewolf lad. Another was Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook (ND/NF, 2014), named for a boy’s malevolent pop-up storybook in Australia. The werewolf film has an unhealthy obsession with Marjorie Estiano’s pregnancy at 28 weeks, and how her stomach is steadily expanding and shifting after her ill-considered one night stand with a lycanthrope. Maybe that was a premonition of decidedly untraditional things-to-come.

Titane, already Ducournau’s hotly debated sophomore feature, is a maverick horror/fantasy of staggering originality. In part it resurrects a 20th century sliver of fiction which the pulp magazine Weird Tales gathered in through the 1930s and 40s. Writing for a penny a word, macabre authors like H.P. Lovecraft, Hugh Cave and Robert E. Howard held sway over a genre that pushed the speculative gaze of science fiction into the weird menace of science fantasy.

As a movie, Titane’s core concept would have fit right in, because it’s a what-if? inquiry never asked before. What if a ferociously healthy young woman, who’s survived a childhood car accident and carries a titanium plate in her skull, somehow becomes intimate with a muscle car, getting pregnant from that one night stand? Could such a hybrid conception occur? How would it be visualized on a huge screen? And would this fearless woman give birth to a daughter, a son, or something else? (Writer/director Ducournau has told audiences that her concept grew out of her nightmare in which she gives birth to auto parts,) Mercy, Titane’s possibilities are endless!

Given this engine that drives Ducournau’s revved-up pulse pounder, it won’t surprise you that Titane at times wants to grind the viewer down into road kill. The grown-up Alexia (Agathe Rousselle, beyond any doubt a stunning newcomer from the top of her hair bun that’s secured by a thin metal rod, all the way down her svelte frame to her tippy toes) has chosen an unusual occupation: She’s an exotic dancer at high-end car shows. Alexia performs the usual grinds and bends with calculated abandon to a guy crowd dripping with testosterone—imagine a car show with the loopy, strobe-lit, ear-splitting club environment Katherine Bigelow created back in Strange Days.

When one doofus follows Alexia from this extravagant salon to a deserted parking lot and asks for an autograph, then a kiss, Alexia embraces him, then unleashes her weapon of choice—that thin, sharpened hair rod that penetrates flesh like butter. This triggers a killing spree in which the hair rod works overtime on a series of meandering males who get in her face. Alexia’s wanted poster—an artist’s conception of that grim face—starts to appear on public media throughout France. We’re waiting for this unhinged femme fatale to be spotted and captured.

But the fugitive years earlier noticed and remembered a missing child poster for a boy named Adrien. Alexia decides to become the young man Adrien would have grown up to be. She disguises herself, shaving her head and taping her breasts as well as her more than ample stomach, which is starting to show and distend, scene by scene and month by month. She breaks her own nose so it mutates into a twisted lump, making her resemble Grimhilde, the evil witch in Disney’s Snow White and the 7 Dwarfs. We also grow increasingly aware of her chest tat, a bold all-caps inking reading “love is a dog from hell.” Alexia, who’s almost completely mute throughout the entire film, doesn’t seem to be longing for a pet as much as someone to somehow replace her own unfeeling parents, whose house she’s burned down along the way.

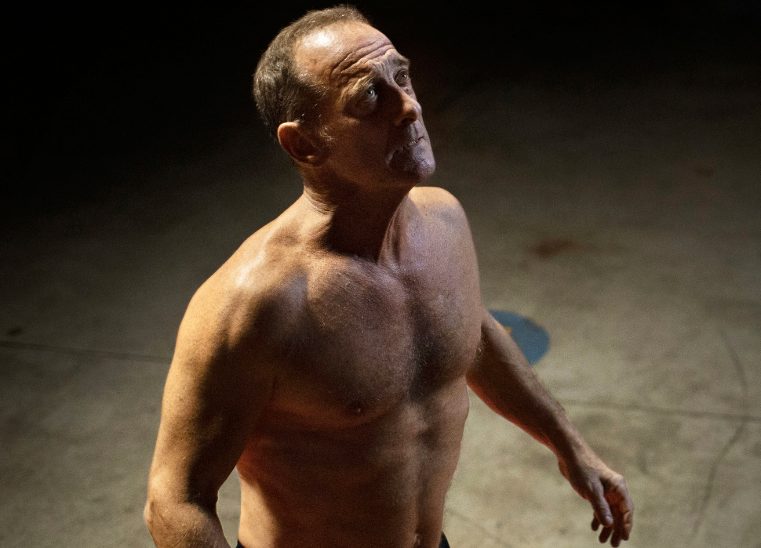

Alexia finds the perfect foil in Adrien’s dad, Vincent (the grizzled and perfectly cast Vincent Lindon), who plays the ultimate heroic authority figure in France—a commandant in the country’s fire service. In America we’d call him the Fire Chief. He’s a hero to all the pompiers in his ladder company—bristling, efficient, a consummate pro who’s first to enter a blazing building. You could easily picture the actor playing one of New York’s Bravest. He also describes himself as “old,” and for a while you may think the daily injections he gives himself in his buttocks are for diabetes and not shots to boost his physical prowess. (Lindon trained for nearly a year to beef up for this role.) Vincent is mourning the memory of his missing son, and when Alexia enters his life, he chooses to believe what his eyes and instincts keep telling him simply can’t be true. Titane thus invents a totally different platform from the familiar mother/son closenesses of Good Manners and The Babadook. Little by little, Titane elevates into the oddest, most strangely compelling father/daughter duo imaginable.

Are you among the audience this search for unconditional love will appeal to? Neon, the super-savvy indie distributor that unleashed Parasite onto world screens, winning Oscars for Best Picture, Director, Original Screenplay and International Feature, certainly hopes so. That film became the first Academy Award winner from South Korea, as well as the first non-English language picture to take the top award. Could Titane achieve similar heights as the first movie that evolves from a sex scene between a dancer with muscles and a muscle car? Hold on, viewers, this is one humpy, bumpy ride that may have just begun.

Drive My Car: Ryûsuke Hamaguchi: Japan: 2021: 179 minutes

The ideal way to prepare yourself for this demanding three hour drama is a deep dive into Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, his turn-of-the-century four-act Russian stage masterpiece. It’s always held contemporary appeal, most recently staged and filmed in a British production starring Toby Jones and Richard Armitage. Chekhov’s characters endure unending suffering, hoping for a better life or at least a graceful death. Hamaguchi’s captivating idea is to picture these struggling characters in a play-within-a-film— auditioning, reading. rehearsing and performing Uncle Vanya, a multi-national ensemble speaking in their own Mandarin, Japanese and Tagalog languages. One major female role is performed signed in Korean Deaf Language.

Hamaguchi’s exceptional widening of a short story by Haruki Murakami crosscuts the plot progressions of Chekhov’s work into a tingling, rapturous exercise of life imitating art imitating life imitating art. A 40-minute prologue before the title credits sets the stage: Yûsuke (a perfectly cast Hidetoshi Nichijima, feeling and sensitive) is an actor/director in mid-career who’s experienced shattering turns of fate—the loss of a 4-year-old daughter to pneumonia, the death of his wife, Oto (Reika Kirishima) from a cerebral hemorrhage, a car accident from a glaucoma blind spot that signals his steadily diminishing vision.

We watch Yûsuke start to rebuild his life, acting in Waiting for Godot and playing the title role in Vanya. He’s excellent in both. Yûsuke accepts an assignment from the Hiroshima Arts and Culture Center to cast, rehearse and direct a two-week production of Vanya. The one condition he reluctantly agrees to is having the Saab 900 he pilots everywhere be driven by Misaki Watari (Tôko Miura) an expressionless 23-year-old female chauffeur (the same age his daughter would have been had she lived).

The director’s fondness for his old car is linked to the audio tapes he uses to learn lines, with his deceased wife reading all the parts except his. Even after her passing, he’s drawn to her memory because “she betrayed me so naturally while she loved me.” Drive My Car is crammed with these tiny, interlocking details, coincidences and secrets that Hamaguchi has painstakingly worked out with his co-scriptwriter Takamasa Oe. Their movie, like Chekhov’s play, never stops surprising you.

Vanya’s administrator and dramaturg both assume Yûsuke will cast himself in the title role, since he’s played the family’s aging patriarch to acclaim. Instead Yûsuke awards the role to a handsome, ill-tempered television star in his 20s, Kôji (Misaki Okada) who’s clearly not right for the role and who Yûsuke reveals was one of his wife’s many lovers. Perhaps it’s an act of cunning revenge to humiliate the moody, conniving lad, but here, too, fate will intervene.

Yûsuke also unknowingly casts the deaf wife (Yoo-rim Park) of his dramaturg (Dae-yong Jin) in the key role of Sonia, Uncle Vanya’s daughter from a first marriage and the playwright’s conscience. This is surely the first time you’ve witnessed Chekhov’s philosophies signed in performance by a superbly skilled actress, and it signals a new dimension in stage interpretations. (Her husband, who’s multi-lingual as well as a fluent signer, translates in rehearsals, while the actual theater audience reads supertitles as you read subtitles.) Yamaguchi has thought out every twist and turn; you’ve rarely spent three more engrossing hours in the dark, as his erudite screenplay smoothly carries you from slower lanes to quicker paced plot turns.

Another defining layer of Drive My Car evolves from the gradual interest that develops between Yûsuke and his driver, a woman with her own tragic past. The director invites her into the play process, permitting Watari to watch rehearsals and accompany him to dinner at the dramaturg’s home; she’s also the fly-on-the-wall as Kôji takes a ride with his director and spills out more of the illicit life he led with Yûsuke’s wife. And when the play is stopped in its tracks by a casting dilemma Yûsuke must somehow resolve, he asks Watari to drive him anywhere to clear his head. Their destination takes them to the site of the young woman’s own loss.

Before this festival, Hamaguchi’s crowning achievement was a 317 minute dissection of the lives of four contemporary women living in Kobe, Happy Hour. (Critic’s choice, ND/NF 2016.) Like Drive My Car, Happy Hour was a stimulating hybrid, in that film the reading of a long novella that parallels the life of one of the women. Hamaguchi fashioned multiple endings onto Happy Hour’s five hour exploration, just as he does in Drive My Car, but none are more powerful than the concluding moments in Vanya in which Sonia, facing a capacity audience with her arms draped around the shoulders of her seated and broken uncle, signs the playwright’s final lines anticipating an afterlife: “We shall see all evil and all our pain sink away in the great compassion that shall enfold the world. Our life will be as peaceful and tender and sweet as a caress. I have faith. I have faith. …We shall rest. We shall rest.”

Passing: Rebecca Hall: USA: 2021: 98 minutes

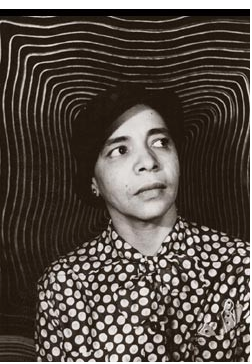

It’s a pleasure to report that Rebecca Hall’s debut feature, Passing, captures Nella Larsen’s slim 1929 novel, barely more than a novella, with merciless fidelity. Easily the best American drama presented at this Manhattan fest, it’s a cautionary tale of life as it was once lived in 1927 along Striver’s Row, an enclave of Black-owned, three story, single-family homes on 138th and 139th Streets, from Adam Clayton Blvd. to Frederick Douglass Blvd.

Most included private gardens and staffs with housekeepers and cooks. Some families owned horses, kept at nearby stables. The properties cost upwards of $8,000 starting in 1919. Most stakeholders were MDs and at the top of their professions, including a heady infusion of arts performers and entertainers including Fletcher Henderson, W.C. Handy and Bill (‘Mr. Bojangles’) Robinson. Their homes and Striver’s Row were one residential pillar of the Harlem Renaissance.

Larsen, who died in 1964, was a nursing school graduate of mixed-race heritage, who became a children’s librarian. She married a Black academic and wrote one other novel plus assorted stories. Her closest white friend, significantly, was Carl Van Vechten, an eclectic author, photographer and bon vivant, to whom she dedicated Passing. Van Vechten, known around Manhattan as “a downtown man who worked uptown,” is most remembered (and sometimes savaged) for a novel whose title is a pejorative for the segregated balconies of movie theaters. He’s a prominent character (Hugh) in both Larsen’s novel and Hall’s movie, adroitly acted by Bill Camp.

Director Hall wastes no time establishing the Passing premise. Irene Redfield (Tessa Thompson), lady-of-leisure, active charity volunteer, mother of two fine young sons, wife of a successful physician, Brian (a splendid Andre Holland) is having tea in a midtown hotel salon shot through with sunlight. She encounters a former classmate, Clare Kendry (Ruth Negga) who at first she doesn’t recognize. Socially and economically, they’re contemporaries. The big difference Clare reveals (in the bright sun that further whitens her light skin) is that she’s been passing for white for years, married to a virulent, white Chicago banker who somehow hasn’t figured out she’s Black. Clare wants to reestablish her friendship with Irene while her volatile husband John (Alexander Skarsgård, bitter and barely civil), who she married at 18, attends all those banking meetings during their New York visit.

Director Hall draws you right in. Beside this unsettling revelation, we observe how the outside world is clawing away at the Redfield’s serene existence. Irene and Brian’s sons are hearing sex jokes and racial slurs at school. A lynching story angers the father into family eruptions. Both parents are close with Hugh, but he’s the one white man who’s reporting how white New Yorkers are flocking to Harlem to stare with a mix of curiosity and disdain at exploding Black culture. When Brian drives Irene to her duties organizing a Negro Welfare League dance, their car gets stuck behind the usual NYC garbage truck. And now here’s this Chicago lady, flaunting her white charade and shaking Irene’s righteous pride in her darker skin. Clare’s always on, forever skating on a thin surface of ice that’s on the verge of collapsing under her. No wonder Brian says he’s ready to pack it in and move his practice and his family far away, maybe Switzerland where Clare’s kid attends a fancy boarding school.

Hall, whose maternal grandfather was Black but passed as a white man for most of his life, infuses her first film with assured artistry. By hewing closely to the events of Larsen’s novel and using much of its dialogue as written, Hall imagines a movie that would sound and look like the book if it had been made a century ago. Passing is in black-and-white and standard, postage stamp ratio (like Coen’s Tragedy of Macbeth). Hall’s production design, cinematography and music follow through with a gravitas and texture that, scene by scene, darken the mood.

You get a whiff of unease when Irene notices a man collapsed on a crowded midtown avenue in the first moments. We note her home is expensively, formally filled with the heavy, brown wood furniture of the era—it bespeaks wealth but it also feels like a museum that needs constant attention from the servants that keep it dusted and polished. Piano fills, artfully improvised by Devante Hymes, that bridge scenes like musical intertitles, have a skittish, trilly cadence that’s unnerving. Somewhere on the Redfield’s block there’s a lone horn player practicing a muted lament. Autumn leaves segue into a cold, snowy December. It seems inevitable that Clare’s destabilizing presence in the lives of this New York family is a bad, bad omen.

Thompson and Negga are truly marvelous in their roles as polar opposites on either side of the color line. Irene draws deep upon her integrity to protect a sense of propriety, order and security she’s surrounded herself in, which Clare constantly threatens to overturn. And Clare, having successfully disguised herself as a white woman of infinite means, finds herself aching to return to a Black world she no longer fits into. Clare wants desperately to present herself as both Black and wealthy, like her soul sister. Only Irene senses how dangerous a game Clare is playing. Negga and Thompson give a master class in acting that’s completely new to 2021 screens. This is a phenomenal debut for Rebecca Hall.

Two shorts long on artistic invention

Through most of the 20th century, short subjects were the added value at your neighborhood movie theater. A newsreel. A cartoon. A 12-chapter cliffhanger or a Pete Smith Special on newfangled suburban living. Shorts were the appetizer before the feature film. They can still be that, as well as standalone artistic achievements of the highest order. Often they’re a young director’s calling card, but not always.

Your critic watched all 34 of this year’s NYFF shorts, selecting two by accomplished storytellers. Each focuses on an of-the-moment reality that’s in our faces and lives. Both interpret these realities in ways that expand rational thinking, embracing the imagination with abandon. Both conclude with blackouts. Each is a unique one-off—an execution of concepts their directors will own forever. Each is gripping beyond words:

Night Colonies: Apichatpong Weerasethakul: Thailand: 2021: 14 minutes

If you dial up the trailer for a new feature film, The Year of the Everlasting Storm (not selected for this festival), you’ll quickly gather it’s seven short, dramatic takes on the Covid pandemic, each contributed by a different director. Apichatpong’s Night Colonies is the concluding 14-minute segment. There’s a moment in the trailer when you’ll see the surface of a sheeted bed crawling with insects, under these superimposed words: “…And those who had disappeared.” That empty bed is the subject of Night Colonies.

Apichatpong is an architect of what’s come to be known as slow cinema,which might be described as All-At-Once-Nothing-Happens-Until-You-Start-To-Feel-It’s-Already-Happening. Like riding in a subway car and slowly realizing most of the unmasked riders in the car are standing above you or sitting on either side of you, huffing and wheezing. The pretty butterfly pictured here is a good example; it alights on the sheet and is immediately sighted by an ant, which busies a path across the sheet toward it. The butterfly flutters up and away just in time.

Where is this bed with its overhanging fluorescent lights? If you know the context, one uneasy thought that may creep into your subconscious is that it may be in some makeshift rural hospital, maybe in Thailand. Or worse, some abandoned makeshift rural hospital, anywhere. From time to time, there’s a murmur of voices mixed with the hour-of-the-wolf activities of the various aphids, mosquitos and assorted insects devouring each other and crawling under the pillowcase and sheets. One voice-over comment is “even the cat was scared when we yelled at each other.” Then a skinny two-foot lizard crawls down the bed pole.

In its fascinating way, Night Colonies is a living visual landscape of what the eminent film critic Manny Farber once defined as termite art—content in which the participants are “ornery, wasteful and stubbornly self-involved.” Shown from the bottom up through a pane of glass connected to the bed, the lizard may remind more than one viewer of Tom Cruise inching along some Mission Impossible landscape.

As sound recorder, editor and director, Apichatpong is in complete control of his micro universe of swarming visitors. He concludes his segment with the multiple fluorescent lamps that light the bed flickering out, one after another after another. Blackout. Watch the trailer for The Year of the Everlasting Storm again, for its ambiguity. The last scene in the trailer, in another episode by another director, shows a father and son cuddling in bed. The son asks, “Daddy, when can we go out again?” And the father replies in a neutral voice, “It will all be over soon.” Brrrr.

2 Pasolini: Andrei Ujica: 2021: France: 10 minutes

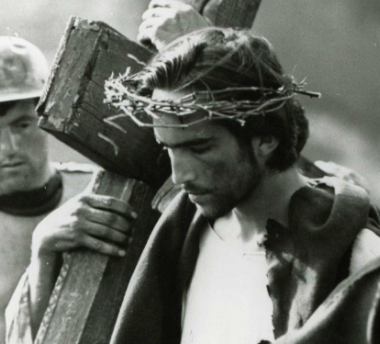

Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975), a provocateur director grounded in Italian neo-realism, was a darling of the New York Film Festival in the 1960s and ‘70s. Four of his feature films were shown by NYFF in little more than a decade—The Hawks and the Sparrows, Accatone, The Decameron, Salo or the 120 Days of Sodom. But NYFF passed on the drama he’s best known for—The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964). It won the Silver Lion at Venice, Grand Prize at the International Catholic Film Office, and was nominated for three Oscars.

Pasolini filmed entirely in the rural Italian region of Basilicata and its capital city Matera, casting non-actors, mostly peasants including a commanding 19-year-old, Enrique Irazoqui, as Jesus. Significantly, his screen adaptation is, word-for-word, a literal translation of Matthew’s Gospel. For years Pasolini’s faithful script has been cited as a major reason for the drama’s enduring reputation as a hallmark of world cinema.

Enter Andrei Ujica, a Romanian film professor and director of the well-received 2010 documentary, The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu. In 2000 Ujica was invited by Foundation Cartier in Paris to create a short film on the meaning and impact of Pasolini’s Gospel. Opening with several minutes of documentary footage of the director inspecting (and rejecting) mountainous sites near Tel Aviv—in the still pictured above—Ujica then transitions to scenes from the movie. His focus is on Jesus’ return to Galilee, especially his rebukes against how the Law of Moses is interpreted by the scribes and the Pharisees. Ujica views Pasolini’s Jesus “as a proto-revolutionary, a revolted artist like himself.” (Note from Ujica, 9/14/21). He wants to show two sides of Pasolini’s personality—“his catholic education and his atheist-Marxist beliefs.” And so Matthew’s text, in his chosen scenes of Christ’s preaching, is filled with anger, rage and “unquenchable fire:”

“Woe upon you, blind leaders, who say ‘If a man swears by the temple, it means nothing, but if he swears by the gold in the temple, his oath stands.’ You blind fools! Woe upon you, hypocritical scribes and Pharisees. …You outwardly appear righteous to men’s eyes, but inside you are full of hypocrisy and wickedness. …You build tombs for the prophets, and decorate monuments to the righteous, and say: ‘If we had lived in our fathers’ time, we would not have murdered the prophets.’ Thereby testifying that you are the descendants of those who murdered the prophets. …You will become answerable for spilling the blood of all just men, from the blood of the just Abel, to the blood of Zachariah, whom you slew between the temple and the altar. This generation shall be held responsible for all of it!”

At this point, Ujica’s screen goes to black, and holds on black while the director plays a new mix of the work he had experimented with back in 2000. The work is Hit ‘Em Up by the late Tupac Shakur, released in June, 1996. It’s a violent, profanity-laden diss track directed at a rap rival and a record label executive. Three months after its release, Shakur was assassinated. Anyone reading the full lyrics (available at the click of a keyboard) will agree it’s filled with anger, rage and unquenchable fire. Ujica titles his track 2 Pac 2 Pasolini. Here’s a sample of Tupac’s original:

I’m from N-E-W Jers’

Where plenty of murders occurs

No points or commas, we bring drama to all you herbs

Now go check the scenario

Little Ceas’ I’ll bring you fake G’s to your knees

Copping pleas in de Janeiro

Little Kim, is you coked up or doped up?

Get your little Junior Whopper click smoked up

What the fuck, is you stupid?

I take money, crash and mash through Brooklyn

With my click looting, shooting and polluting your block

With a 15-shot cocked Glock to your knot

Outlaw MAFIA clique moving up another notch

And your pop stars popped and get mopped and dropped

And all your fake ass East coast props

Brainstormed and locked

The issue, dramatically, is how Matthew’s Gospel, heard against footage of stormy ocean waves, plays against Shakur’s recording, heard over a black screen. Does it work as art? This is for individual viewers and listeners to decide. Ujica is pushing boundaries just as Martin Scorsese did with The Last Temptation of Christ. Here it’s angry scripture vs. angry rap. NYFF showed this short in a section currently titled Currents, which used to carry the more lofty and less inclusive title, Views from the Avant-Garde. Times are changing.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 12th annual DOC NYC, America’s largest documentary festival, November 10-18.

Regions: New York City