Tribeca Festival June 8-20

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw reviews favorite features and shorts with a definite New York accent

‘The city that never sleeps’ has awakened to two renamed institutions since the onset of Covid: The 92nd Street Y is now known as 92NY, signaling a momentous decision to begin streaming much of its top-drawer cultural programming to the world. And the former Tribeca Film Festival’s 22nd season of multiple events on a myriad of platforms, (including 110 feature films and 43 shorts on big screens in downtown Manhattan as well as Tribeca At Home), continues under its shortened name, Tribeca Festival.

The original goal of the festival, founded in 2001 by Robert De Niro, Jane Rosenthal and Craig Hatkoff, was to spur the economic and cultural revitalization of lower Manhattan following the attacks on the World Trade Center. Today, the festival continues to attract urban dwellers and global tourists to the stores, shops and theaters of the same neighborhoods as the city trudges into its third year adapting to Covid. Its platforms have widened to include storytelling in TV, VR, gaming, music, online work and immersive entertainment. It introduces new technology and ideas through premieres, exhibitions, talks and live performances.

Lots to unpack here. Both the opening and closing night premieres documented marquee personalities: Amanda Michel’s Halftime, shown at the historic United Palace in Washington Heights, traced the career of global superstar and Bronx native Jennifer Lopez. Josh Alexander’s Loudmouth chronicled the life and times of Rev. Al Sharpton, from 8-year-old Brownsville-born preacher to presidential candidate advisor and racial justice advocate. Talks covered Black representation on screen and Black women’s creative processes, Broadway’s comeback, JR’s street art, sustainable film-making, youth workforce development, and even the duties of the intimacy coordinator. There were immersive looks at climate change, LGBTQ stories and artwork, indigenous Canadian life, and Shakespeare’s Iago.

Independent episodic work focused on Pride and Juneteenth, Queer and Black creators , oppression in America and the legalization of marijuana. Live music shows featured performances on drum machines, ‘underground’ DJs, and a Battle of the Bands. Among the gaming concepts were future metropolises, electromagnetic landscapes, medieval tales and trips from Mars to Earth. Audio storytelling favorites included Oprahdemics podcasts from the Oprah Winfrey team, life aboard a space travel diner, and Bernardine Dohrn’s years in the Weather Underground. TV highlights spotlighted The Captain himself, Derek Jeter, global explorations by science guy Bill Nye, and the history of the Supreme Team (a Queens’ street gang). The venues for all this cultural activity were spread around NYC and were hosted by the Beacon Theater, Pier 57, Spring Studios, BMCC Tribeca Performing Arts Center, SVA Theatre, Village East by Angelika, Cinepolis Chelsea, Waterfront Plaza at Brookfield Plaza, and Battery Park City. Tribeca’s slogan ought to be Too Much Ain’t Enough.

Your viewer, again staggered by the endless menu (not to mention 90 degree+ summer temps and a downtown Covid infection rate hovering near double digits), hunkered down with virtual viewing plus some pre-festival screenings hosted by publicists. The two week Tribeca At Home innovation —a curated selection of online narrative films, docs and shorts— was also available to all through June 26. It was easy cozying up with New York based content, filmed in and around Manhattan and the five boroughs, just as Tribeca’s curators did in choosing their Opening Night and Closing Night selections. Here are five critic’s choice features and shorts, also all documentaries of the first order:

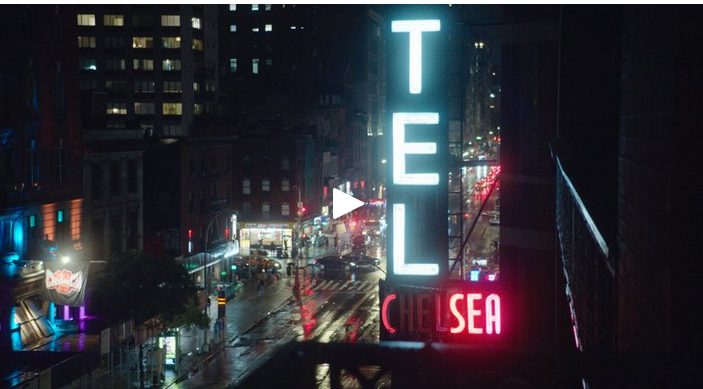

Dreaming Walls: Inside the Chelsea Hotel: Maya Duverdier, Amelie van Elmbt: France, Belgium, United States, Netherlands, Sweden: 2022: 80 minutes

One scene in this Manhattan gem makes it the perfect art cinema doc for cranky bohemian seniors. Especially those who’ve lived through any legendary Manhattan renovation-from-hell. For long time residents paying as little as $317 a month, resisting being ousted from their residences on West 23rd St. at the Chelsea Hotel, it’s nine years and counting. The misery index within these bulldozed walls, even before Covid, seems awfully high.

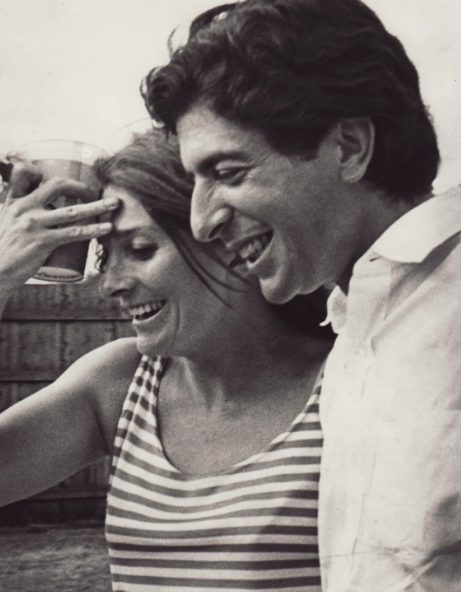

The chap in one contemplative scene, Steve, is a pleasant, rueful dweller since 1994. He’s snagged #411, once a spacious apartment occupied by Janis Joplin. There’s an indelible history infused in her pad, though it’s not told by Steve, of Janis and a folky poet named Leonard Cohen sharing a night of intimacy back in 1968. It seems that Janis was dropped off by limo after a recording session, considerably under-the-influence, having been advised she’d meet some new dreamboat she’d only heard about, named Kris Kristofferson. Cohen, who was rooming at the Chelsea, introduced himself and passed himself off as Kristofferson. (Their night is explicitly detailed in Cohen’s “Chelsea Hotel No. 2,” heard in the fabulous new doc, Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah, which is up next in these critic’s choice reviews). In Dreaming Walls, resident Steve bleakly describes the “slow-motion rape” of his home by building owners who’ve progressively removed what was Janis’s bedroom, kitchen and bath, leaving him jammed into a tiny studio. Steve sadly points out a partitioned wall that held Joplin’s toothbrush holder.

Dreaming Walls is full of anecdotal laments like this, hinged to legendary celebrity neighbors who visited, partied at and even lived at the ornate Chelsea. Directors Duverdier and Elmbt (with a supervisory nod by exec producer Martin Scorsese) superimpose a gallery of images led by Warhol, Monroe, Burroughs and Ginsberg on the brickwork. A very young Patti Smith enthuses that “Dylan Thomas used to write on this very roof,” and as she points to the Empire State Building, laughs that “I’ve always wanted to be where the big guys are!” The camera prowls through corridors crammed with work crews, electrical wiring, sheetrock, whining drills, ground-floor hoists and earth movers, elevators rumbling up and down all day outside scaffolded windows. Plastic sheets with zippers cover much of the Chelsea’s bones. “How are you feeling today?” chirps the lady at the desk to one elder tottering in. “Terrible, terrible,” is his sharp-elbowed reply.

This oddly engrossing documentary is mounted with what documentarian Frederick Wiseman defined as “a novelistic rather than journalistic or ideological” perspective, “with the camera and microphone moving as parts of our bodies.” While there’s a deftly composed and mixed score matching the mood of many scenes, there’s no expositional framework or helpful voice-overs. You’re on your own weighing who’s a reliable narrator among the many reflective tenants, as well as their imposing residential manager, Stanley Bard, who insists he’s on call 24/7. Bard champions “fun people and flexible management,” and seems to enjoy a close relationship with famed artist Larry Rivers, who signs a massive 1964 work adorning the Chelsea lobby. Residents are less than thrilled with the “poor man’s elevator” in the back that their landlord appears to have exiled them to. Some believe it will be a permanent fixture when the Chelsea is finally converted to luxury apartments.

A lot of this doc’s irresistible snooping comes with being invited into the homes of working artists, wire sculptors, painters, dancers and composers, and seeing the increasingly compressed decades of lives. Behind the doors of people like Virgil Thomson, Merle Lister and the late Bettina Grossman (who passed last year and is known at MoMA and worldwide as the artist Bettina), a delicious history stubbornly remains. Gorgeous paintings, turn-of-the-century stained glass and rooms of brown furniture attest to taste and preservation. There’s a steely resolve among these self-described New York drama queens that sometimes erupts in spontaneous dancing and celebrations, right in the hallways. It ain’t Park Avenue.

The restless roving camera of Dreaming Walls, constantly poking into the disappearing homes and lives of the Chelsea, bears an uncanny resemblance to a Tribeca short of 2016, Ellis. It was directed by the Tunisian wheatpaste artist JR and co-produced by Tribeca co-founder Jane Rosenthal. JR explored the interior of the Ellis Island Immigration Hospital, still standing in stately ruins in New York Harbor 90 years after its closing. What JR fashioned was a permanent installation of collages of faces of hundreds of immigrants from the first decades of the 20th century, not unlike the collages of celebs played onto the Chelsea’s brickwork by Dreaming Walls’ directors. One immigrant in Ellis is acted by Tribeca co-founder Robert De Niro, whose character is rejected by the hospital doctors, who order him back. “Back where?” wonders De Niro. “Back where you came from,” is the answer.

Chelsea’s elderly residents don’t have this option. They’re already home, often with no place to return to, if they’re forced to give up their apartments, piece by piece. In a tearfully moving conclusion, we follow one aged resident onto her generous terrace overlooking a bustling 23rd Street, then dissolve to her pushing her walker doggedly, determinately, down a busy Manhattan sidewalk toward—where? We don’t know.

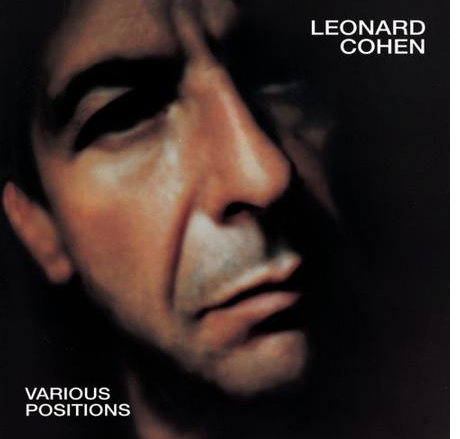

Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song:Dan Geller, Dana Goldfine: USA: 2022: 118 minutes

Unlike the random, wandering journey through the Chelsea Hotel, Leonard Cohen’s shimmering, double-platinum biopic is crafted to an inch of its life. It’s so impeccably assembled, you instantly settle in, trusting its five power-pointed sections (plus an epilogue) will journey you to a full understanding of Cohen’s mammoth gifts, as well as his richly turbulent and damnably conflicted life (1934-2016). Does it ever.

If you’re especially a fan of Cohen’s signature anthem, Hallelujah, which has been covered by 300+ artists and streamed millions of times since its release in 1984, rejoice! A solid hour focuses on the hymn’s creative evolution. The picture is co-executive produced by Morgan Neville and distributed by Sony Pictures Classics. It’s imperative that Leonard Cohen, surely our most beloved spiritual troubadour next to Dylan, be honored right, from its pre-production through its release.

Geller and Goldfine fly you first-class, The scrumptious continuity, tiny detailing, the constant interweaving of essential and accidental snippets, the examination of Cohen’s diaries, his jottings, musings, crack-ups, longings, all his ponderings over a feminist God, all his sexual intuitions that cut to the quick—every bit is seamlessly integrated. You feel him scratching his head, staring at his typewriter, teasing a reporter, pounding his head on the rug as an elusive lyric evades him, sometimes for years. The braiding of Hellelujah’s sacramental verses with their eventual secular counterparts has never been this exhaustively detailed. His ping-ponging between what a rock reporter calls “holyness and horniness” has never been so thoroughly revealed in one sitting.

Two people in Cohen’s life who betrayed him are called on the carpet: The late Walter Yetnikoff, a head of Columbia Records, killed Cohen’s 7th studio album, Various Positions (which included the first pressing of Hallelujah) in ’84. Cohen recalls the notorious cross-addicted mogul starting conversations “reviewing my suits.” Passport Records, a small indie label, released Various Positions a year later; on Ebay today it fetches $60. The other bad guy was his female manager for 17 years and a trusted family friend, who Cohen sued for engineering the embezzlement of millions of dollars, including nearly all his retirement funds. (“I had nothing left, even on my ATM card. I had to start over fresh at 70.”)

His subsequent touring and recordings would become, irony of ironies, his greatest triumphs and indelible pieces of his legacy. Cohen’s years with Suzanne Elrod and their two children remain in this film’s shadows, and only one of his countless lovers gets significant screen time—photographer Dominique Issermann, who’s pretty sanguine about being Leonard’s first ‘real love’ at 52 and to whom he dedicated the song and album I’m Your Man.

The major players who’ve contributed to Cohen’s professional life have been lovingly assembled, bringing their A-game: Rolling Stone’s Larry “Ratso” Sloman anchors the proceedings as Cohen’s closest confidante. Canadian arts administrator Adrienne Clarkson was a pioneer in spotting and touting Cohen’s early gifts as the poet and author of Beautiful Losers. Judy Collins, at 83 still our quintessential folkie, first covered his inimitable Suzanne (“Leonard was intelligent, mysterious and dangerous, and when I passed 25, I knew dangerous when I saw it.”)

John Lissauer, now in the Grammys Hall of Fame, produced, arranged and conducted Cohen’s original Hallelujah. (“Working with him was like Kurt Weill loving Berlin in the ‘30s”) Singer/songwriter Sharon Robinson, his lead backup singer, became his co-arranger and producing partner. (“He was comfortable in life, but he was conscious of people who weren’t comfortable in life.”) Rabbi Mordecai Finley, his spiritual advisor, explains the Jewish tradition which led Cohen to consider changing his first name from Leonard to ‘September.’ Singer/songwriter Brandi Carlile summarizes how when her life was desperately hard, Cohen’s work was the bridge between her spirituality and sexuality.

Along the way, new insights are provided on how his music survived—well, almost anything and anyone. Producer Phil Spector’s signature ‘Wall of Sound’ couldn’t dent the power of the lyrics. Hellelujah’s scores of versus were explored by Bob Dylan, then John Cale (moving solo from the Velvet Underground), then Jeff Buckley (Tim’s impossibly beautiful son and Hallelujah’s most sexually alluring interpreter), then Rufus Wainwright (heard on the stupendously successful soundtrack of the movie Shrek). Many listeners assumed whoever was singing Hallelujah probably wrote it. You may wince listening to Vicky Jenson, Shrek’s co-director, tell how she surgically removed all the “naughty bits’ from Cohen’s lyrics, thus powering its way to acceptance and acclaim worldwide.

The directors mount a convincing argument—despite Cohen’s affairs of the heart and contemplations of the soul (including a six year retreat into a Zen Buddhist monastery on a mountain). that he was the wisest man in the room, if not the smartest. “All I’ve learned from love is how to shoot somebody who outdrew you” is one of those sad lyrics on passion spent that you’ll remember forever. And when Cohen growls the most immediate line of Hallelujah in every live concert—“I’ve told the truth, I didn’t come here to fool you” the crowd roars its affirmation and gratitude. It’s both a fact and a truth, which is what every songwriter spends a career and even a life going after.

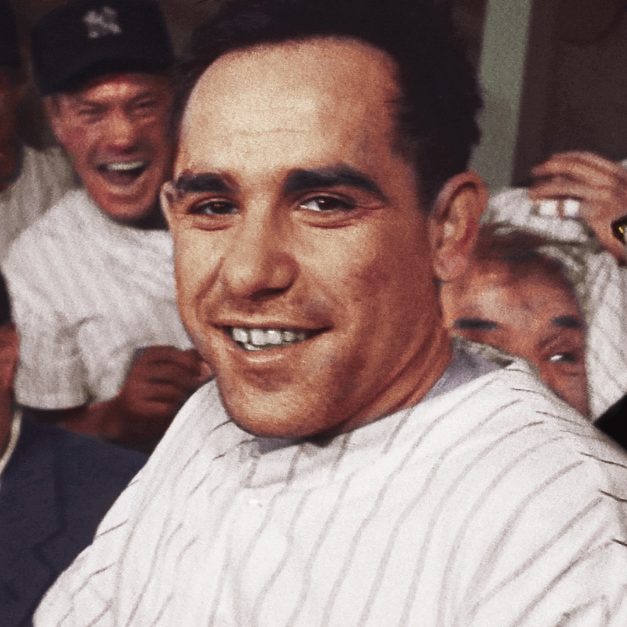

It Ain’t Over: Sean Mullin: USA: 2022: 98 minutes

Feature docs taking on the onerous task of interpreting a beloved New Yorker’s life are the ones New York film critics parse most closely. “You better get this one right,” we mutter as the lights go down. There are only so many icons that keep us going through the best and worst of times in this town, and they don’t grow on trees. Joe Papp in Five Acts, directed by Tracie Holder and Karen Thorsen and premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2012, brilliantly captured all sides of the founder and proprietor of the Public Theater. Richard Press’s Bill Cunningham New York painted an equally astute and affectionate portrait of The New York Times’ style photographer who rode his bike to the corner of Fifth Avenue and 57th Street, and around Manhattan for countless seasons of our lives, forever clicking away on what city dwellers were wearing.

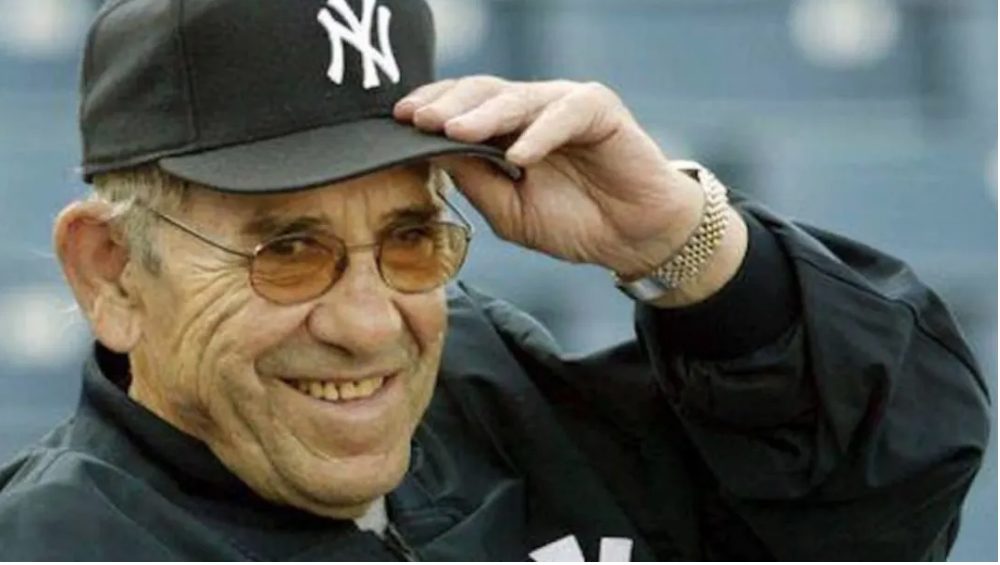

The bar is set even higher for Lawrence Peter “Yogi” Berra, baseball’s archetypal catcher, manager, D-Day veteran, husband, father and Mad Ave pitchman. Yogi was the eternal underdog who distinguished himself in ten World Series and 18 All-Star Games, winning three MVP awards and catching the one perfect World Series game of the 20th century. Director Sean Mullin can start taking victory laps right away— long before next year’s Oscar ceremonies—for putting together a four-handkerchief triumph that’s as peppered with memorable anecdotes and rare insights as the Leonard Cohen bio now on your must-see list.

This is a shrewd baseball bio calculated to win your heart from its opening seconds. Lindsay Berra, one of Yogi’s 11 grandchildren and It Ain’t Over’s driving engine, is showing a clip of the most popular living players (as chosen by fans) during the 2015 All-Star Game. Hank Aaron, Johnny Bench, Sandy Koufax, and Willie Mays take their bows. “More MVPs than anyone, more World Series rings, and my grandfather isn’t among them,” laments an angry Lindsay. “I asked him, ‘Are you dead yet?’ and he replied ‘Not yet.’” Yogi died later that year. Right away you’re hyped up and eager for Yogi never to be forgotten by baseball fans.

Born to Italian immigrant parents in St. Louis in 1925, Berra stayed low to the ground (at 5’7”) and was blessed with large, strong hands, keen eyesight, and remarkable speed on the bases. In his catcher’s crouch, arms crossed, his prominent ears sticking out, it wasn’t surprising parents of other stickball and sandlot players (and later the world) would say “you look just like a yogi.” The name stuck. Here was a kid born for baseball, and a raft of pros (from Roger Angell and Bob Costa to Derek Jeter and Joe Torre) astutely analyze the distinctive physical makeup of a champion. Yogi swing at and hit nearly every kind of pitch; he’s been called “the best bad-ball hitter in the game,” and he rarely struck out. As dutifully noted in one of his inimitable Yogi-isms, “baseball is 90% mental, the other half is physical.”

At 18, Berra enlisted in the Navy and was assigned to a rescue boat during the D-Day landing; he survived withering fire on Omaha beach at Normandy. Back home in ’46, he joined the New York Yankees, a team poised for fame with its growing roster of tall, strikingly handsome athletes like Joe DiMaggio, Don Larsen and Mickey Mantle. Berra didn’t look much like most Yankees, but he was a team player all the way.

Black sportswriter Claire Smith acknowledges how Jackie Robinson’s career was launched with the unfailing support of Yogi, Pee Wee Reese and Ted Williams. And one of the delightful centerpiece scenes of It Ain’t Over examines the moment when Robinson safely steals home during a 1955 World Series game. Yogi lets loose his fury. “He was out!” Berra will be asked about this call the rest of his years, and he never stops insisting he tagged Robinson out. Half the experts here agree; the other half affirm Robinson was safe. You’ll make up your own mind; it’s that kind of movie.

A curious side of pop celebrity descended on Berra in the 60s: he becomes a willing participant in exploiting his own persona. Endorsements for Wheaties and Yoo-hoo share newspaper, magazine and television time with commercials for Camels, Miller Lite, Ballantine, Pringles, Puss ’n Boots, Aflac—the product list is as varied as major ad agencies’ client lists. Overnight Yogi morphed into the funniest, squeaky-clean sports pitchman a marketer could hire, right up there with his pal Joe Garagiola. Maybe the ever-affable, ever-cooperative Yankee was piling it away for his wife, Carmen, and their three sons. The pay days add up—a reported $65,000 in 1961, upwards of $5M in his lifetime.

But Berra paid a price: Yogi Bear became a hugely popular television series, which Yogi was never fond of. The combination of being viewed as a cartoon, on top of shilling for cigarettes and beer, on top of becoming manager of the New York Yankees and then the New York Mets, made the optics appear more than a little weird. For the first time Yogi was pushing a squeaky wheel. It’s said he threw a pack of Camels at a club owner, and we watch him angrily kicking field dirt onto an umpire’s shoes. Narrator Lindsay and the film grow quietly ambivalent about the many hats Berra was wearing, and what’s been an easygoing baseball movie hits a rueful 7th inning stretch.

When business tycoon George Steinbrenner buys the Yankees in 1973, he brings Yogi home as manager a second time—then abruptly fires him after just 16 games, shocking the sports world. Yogi states he’ll never return to Yankee stadium, a vow he keeps for 14 years. During the early 80s, his son Dale joins the team and falls victim to a cocaine addiction that wrecks his 10-year career; a family intervention brings him to the fork-in-the-road Yogi always advises people to take, and Dale chooses the path toward recovery. Berra and Steinbrenner finally reconcile.

Overall, It Ain’t Over (“till it’s over”) is a beautifully played game of life, mostly set during an American age of innocence few viewers today were privileged to grow up in. After his passing, a grateful nation and Barack Obama honored Yogi with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, given to his son. The catcher’s adorable mug adorns a first-class postage stamp. He and Mullin’s admiring doc easily join the Joe Papp and Bill Cunningham movie library of keepers.

Nicholas Brothers: Stormy Weather: Michael Shevloff & Paul Crowder: USA: 2022: 20 minutes

Imagine these two gentlemen in formal attire spinning and kicking their way around Cab Calloway’s orchestra. They’re as carefree (yet as careful) as the breakdance troops who pile onto a #1 subway train and perform an amplified one minute display of wizardly acrobatics right in the aisles, between station stops. There’s only a safety margin of inches between rider and dancer, as there is here between horn players and dancers, so the precision of the performers is everything. This Manhattan straphanger in 2022 trusts the prowess of underground street artists, much as Cab’s horn section trusted Fayard and Harold Nicholas on their bandstand in 1943.

The scene pictured is from 20th Century Fox’s Stormy Weather, one of two Hollywood musicals with a Black cast (headed by Lena Horne and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson), released in 1943. The film was a showcase for what was known in the era as “specialty numbers.’ These would interrupt dramas and especially films noir so the lead female (often a femme fatale) would step out of character and deliver some ballad of fatal love.

The 1943 Stormy Weather had Lena Horne’s moody title song, and that feature was an endless string of specialty numbers, none more spectacular and memorable than the Nicholas Brothers’ “Jumpin’ Jive.” Fayard and Harold were vaudeville veterans who migrated to Harlem’s Cotton Club in the ‘30s, where they entertained primarily white audiences., accompanied by bands led by Calloway and Duke Ellington. “Jumpin’ Jive” was movie great Fred Astaire’s favorite dance feat, and the brothers’ over-the-head leaps and repeated glissando-style slides have rarely been duplicated.

Until now. The magic of this short is how its host, dancer/composer/actor Savion Glover, artfully segues us to the Nicholas brothers’ modern-day counterparts: Laurent and Larry Nicholas Bourgeois, 34-year-old identical twin brothers known as Les Twins. They’ve built their chops worldwide, from Cirque du Soleil to Beyonce. “The word hasn’t been invented yet to describe their contribution to the world of dance,” says Glover. Watching these lean 6’4” dancers execute a choreographed free style in which centers of gravity are constantly changing as they bend and twist, one marvels at their originality. Clearly they’re standing on the shoulders of the Nicholas brothers, but the hip hop influence burns through. Accompanied by a drummer and half a dozen other percussionists, guided by composer/producer Moses Boyd, they give closure to this memorable tribute that’s, in a word that once held real meaning, ‘awesome.’

John Leguizamo: Live At Rikers: Elena Engel: USA: 2022: 25 minutes

The star’s a little nervous, being picked up by a 14-year veteran officer of the New York City Department of Correction. They’re driving out to Rikers Island Correctional Facility, which is 400 acres of separated land holding 10 jails. John Leguizamo’s concluded a run of his one-man Broadway show, Ghetto Klown, and will perform it for an auditorium of inmates awaiting trial or sentencing. It’s a medium-security facility with a high rate of recidivism. Leguiziamo stares at the auditorium as it’s about to fill: “If I can do this, I can do anything,” he murmurs.

Director Engel’s approach, which works instantly, intercuts snippets of the actor’s stage routine with scenes of him talking with and mostly listening to prisoners’ thwarted hopes and dreams for a better life, once they’re free. John calls it a “soul exchange.” As a Drama Desk winner, he’s a skilled, no-nonsense storyteller of his own youth growing up in a Queens’ project, where “my moms says to us, ‘I just looked at the family budget, and one of us has to go.’” On stage, he’s a whirlwind of fast, abrasive and painful memories, salted with an arrest record and no shortage of profanities, and wrapped in a heart as big as New York. He shows a map of the five boroughs on a blackboard, and etches in a penis-shaped Manhattan and a scrotum-shaped Queens. “You’ll never forget the map you’ve just seen as long as you live,” snaps the comedian. Leguizamo kills it.

And off-stage he does something more: Like all great actors, Leguizamo has perfected the art of listening. It’s a gift he carries lightly, and he uses it here, and the younger men sense this guy’s heart is with them; he hears their pain with an intensity that’s palpable. John’s m.o. parallels Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah, when Cohen intones “I didn’t come here to the Beacon Theater to fool you.” On stage and off, John is a messenger of hope, even when he’s reminding his audience that his early screen roles frequently cast him as the drug dealer, the bad guy.

Engel’s wisdom as a filmmaker extends to including one of the most powerful scenes of Laguizamo’s Ghetto Klown staging. He’s recalling when his own father came to see him in Freak, his breakout Broadway engagement. Dad is furious, humiliated by his perception that his son John has shamed him in front of a paying audience. (John is acting both his father and himself.) He’s describing, way deep, from the depths of his soul, how he desperately wanted a father’s love he never received. It’s a scene in which time stands still—one gifted actor passing on to an auditorium of younger men the heartbreak of his youth, unforgettably told.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 60th annual New York Film Festival, Sept. 30-Oct. 16.

Regions: New York