New York Film Festival Sept 26 – Oct 13

American star power artistry (Willem, Ethan, George) dominate the 63rd NYFF at Lincoln Center

It hardly seems accidental that this festival’s gala Opening Night, Centerpiece, and Closing Night selections were all U.S. releases starring familiar names you’ve grown up with in the dark—Julia Roberts as an adulterous Yale professor (Luca Guadagnino’s After the Hunt), Cate Blanchett and Vicky Krieps as visiting daughters of Charlotte Rampling (Jim Jarmusch’s Father, Daughter, Sister, Brother), plus Laura Dern and Will Arnett in a rocky marriage due to his standup comedy gigs (Bradley Cooper’s Is This Thing On?). As you’d expect, all three of these Lincoln Center box office charmers sold out their red carpet premieres in Alice Tully Hall (1,086 seats) in minutes. And there are memorable performances in all three films.

Choosing a handful of NYFF critic’s choices is not simple. There’s the ravishing Anemone with Daniel Day-Lewis, gaunt and volatile, returning to the screen as a divorced dad living as a hermit in a surrealistic northern England. Jodie Foster has also returned to vibrant screen life as a French psychoanalyst whose prescriptions kill a patient in A Private Life. Valeria Bruni Tedaschi, Italy’s workhorse leading lady, couldn’t be a better choice to play the volatile stage actress Eleonora Duse on the eve of post WWI fascism in Duse. And Rose Byrne never lets down her burning intensity as a mom with a kid on a feeding tube, in the aptly titled If I Had Legs I’d Kick You. The NYFF 63 was top-heavy with cream-of-the-crop names carrying solid and often essential movies.

In fact, this edition was top-heavy with movies in all its categories, offering patrons more choices than ever before in Film at Lincoln Center’s history. Its Main Slate alone totaled 34 features from 26 countries. Its Spotlight section presented 12 feature portraits of iconic artists/entertainers, from Bruce Springsteen to Broadway’s Lorenz Hart. Its Currents series, once known by its less inclusive title, Views From the Avant-Garde, offered up 16 features and 24 shorts exploring “the boundless possibilities of cinematic language.” And its Revivals section of 12 movies included Ossie Davis’s lost 1972 Black Girl with stellar actors Claudia McNeil, Ruby Dee, and Brock Peters in full flower, as well as Erich von Stroheim’s silent 1929 doozy, Queen Kelly, starring Gloria Swanson in a lavish production bankrolled by her lover, Joseph P. Kennedy.

All in all, nearly 100 features and shorts—more than any critic, fan boy or girl could possibly view in pre-screenings or during a two week festival. The bottom line is that the number of seats hasn’t gone down in leading indie theaters, but the number of ticket buyers has. This 63rd NYFF was more commercial, thus attracting not just regulars but more sidewalk fan lines and selfie seekers waiting for stars to arrive for screenings and red carpet premieres—less common at past NYFF fests. And the New York Film Festival’s tally is far below the feature count of its downtown festival neighbors, DOC NYC and Tribeca.

What’s at play here, downtown and uptown, are newly altered methods of curating. The prevailing philosophy is being all-inclusive, offering something for everyone. But NYFF’s artistic director, Dennis Lim, offers a more realistic view when he states that “anyone who cares about film knows that it is an art in need of defending, like many of our core values today.” Lim says filmmakers are finding new ways of safeguarding free expression and speaking truth to power.

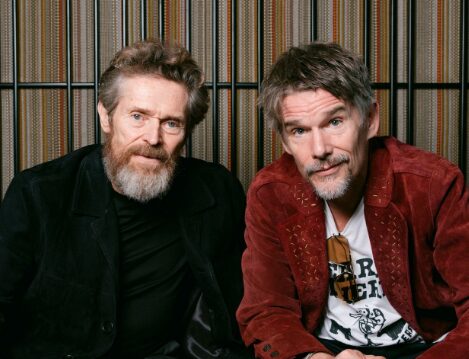

This NYFF edition also continued its impressive schedule of talks, conversations and panels— some ticketed, some free. Among the highlights were Willem Dafoe (Late Fame) in conversation with Ethan Hawke (Blue Moon)… a director’s dialogue between Noah Baumbach (Jay Kelly) and Joachim Trier (Sentimental Value)… Barry Jenkins (director of past NYFF selections Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk) interviewing Claire Denis (The Fence)… and the annual Amos Vogel lecture (honoring the NYFF co-founder, who bridged Manhattan from marginalized underground fare into European art cinema in 1963), delivered by Argentine director Lucrecia Martel. Her first documentary, Landmarks, a Main Slate selection, is a heartbreaking documentary of indigenous people losing their home turf to a corrupt government.

Finally, kudos to FLC for continuing its Artists and Critics Academy programs, the centerpiece of which is a three-day immersive workshop between the next generation of filmmakers and industry professionals. The goal, as always, is to “foster a film culture that embraces diverse storytelling and points of view.” Sometimes this education process trickles down to two people standing in a movie line, as happened when your 87-year-old film critic had a half-hour conversation before 8:00am with a 20-something film major at Manhattan’s School of Visual Arts. One question uppermost on this budding moviemaker’s mind was whether he’d hypothetically accept the financing (and even final cut approval) from a commercial streaming service in exchange for a theatrical window of next to nothing, forever dooming his movie to be watched on a mobile device the size of his palm. The student was conflicted. We agreed a Netflix, Apple, or even an “Amazon MGM Studios” release is a conflict by definition. And there are no textbook answers.

Here are Critic’s Choices for the 63rd NYFF:

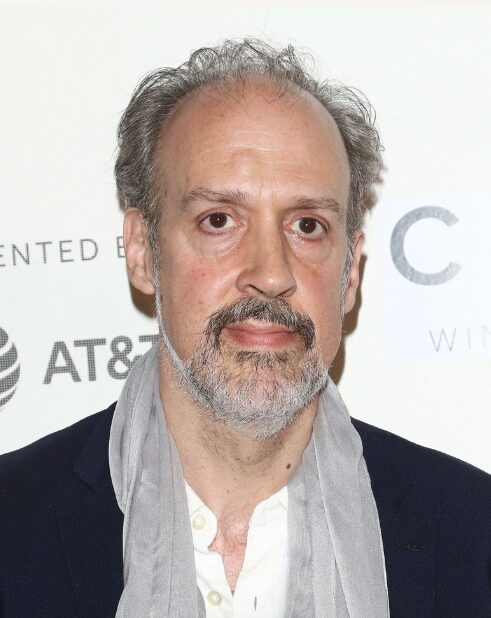

Late Fame: Kent Jones: 2025: US: 96 minutes

Kent Jones is NYFF’s Renaissance director. Jones decided after trying NYU that he could learn movies faster working at Manhattan’s first VHS store. He discovered he could review them, too, writing with the ease, dispatch, and aesthetic insights of a Manny Farber mining termite art—and holding in-person audiences in thrall for hours, lecturing in whole paragraphs about film without a single note. Martin Scorsese hired him as an archivist and mentored Jones’s independent doc studies of Elia Kazan and Val Lewton. He came onboard NYFF’s selection committee in 2002, and when Richard Pena retired after a quarter century helming NYFF, Jones stepped into his shoes.

But Kent really wanted to write and direct, and so he did, co-scripting Arnaud Desplechin’s Jimmy P: Psychotherapy of a Plains Indian, and directing the feature-length doc Hitchcock/Truffaut, based on Truffaut’s essential book. When he elected to devote himself exclusively to filmmaking, Kent was replaced by Eugene Hernandez (now director of the Sundance Film Festival), who once upon a time was a valued news reporter for The Independent. Jones’s first dramatic feature, Diane, was a Critic’s Choice at the 2018 Tribeca Film Festival (when ‘Film’ was still in its name). The feature is a bleak tale of alcoholism and family loss with an incandescent Mary Kay Place playing a figure who Jones has candidly admitted may have been based on his own mother.

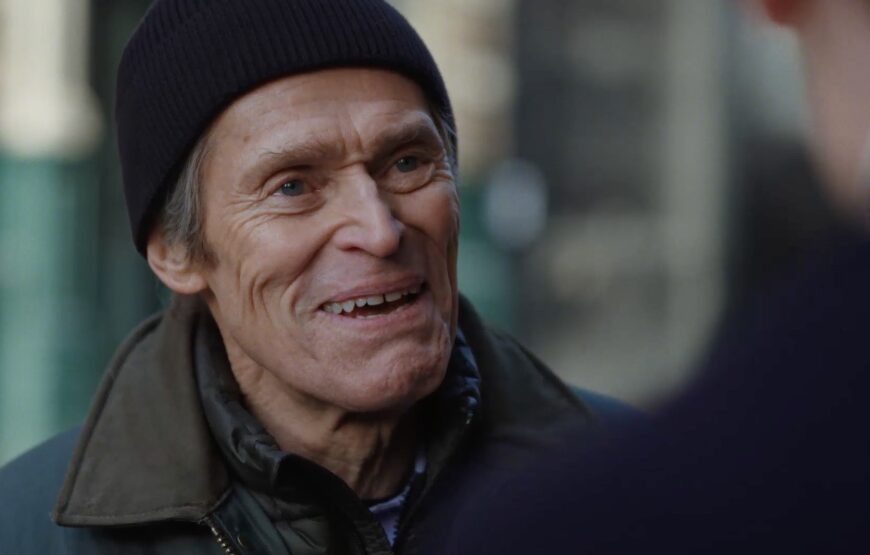

Late Fame is his sophomore drama, and the sweet spot of this fest—the perfect little Manhattan indie movie. It’s executively produced by Scorsese, and co-produced by Christine Vachon, who dollar for dollar, Killer Film after Killer Film, gets more value up on indie screens than any producer on the planet. Soho, Tribeca, and the Village have never looked better behaved, all velvety and smoothed out, as timeless and inevitable as graffiti scrawls in cobblestone. And with Willem Dafoe as leading man, how can you go wrong? (The correct question might be: How could you possibly do any better?)

Dafoe plays Ed, a letter sorter in the post office a short walk from Film Forum. He lives alone in a modest third floor walkup, shoots pool with the guys in a neighborhood watering hole, is sober six years and seems estranged from his family. In his pulled down wool cap and non-descript cargo jacket, Ed still resembles the poet of a 1979 published volume of poetry, Way Past Go, he crafted in a distinct New-York-State-Of-Mind. Once upon a time, Ed tells us, he rubbed shoulders with Robert Creeley and Ed Dorn. He’s like many other Manhattanites who once had their artistic moment and wouldn’t think of moving anywhere else, holding on to memories, rent-stabilized flats, and all the books of a lifetime.

A fan, Meyers (an aggressive Edmund Donovan), turns up across from Ed’s building, hoping to meet the author of the poetry volume he picked up on Charing Cross Road that changed his life. Meyers is an NYU grad with an M.A. who anchors a downtown salon (The Enthusiasm Society) of young poets, essayists, and culture mavens. They’re strictly old school, decrying social media, cell phones and capitalism, “revering the art that binds us together.” They’re also initially all male except Gloria (Greta Lee, dazzling), an actress and singer shopping for her first big break. Ed becomes the salon’s literary lion in winter, and Meyers tries to persuade him to resume a career he’s long forgotten. Ed agrees to meet a frosty literary agent (Jake Lacy, still memorable from Diane) who we sense will do nothing for him. He’s also drawn to Gloria in a tender scene played in Washington Square Park. Moments like these should alert you to the distinct possibility that nothing is ever going to change Ed’s simple existence in Soho.

Dafoe is, above all, a generous actor who listens well and willingly yields scenes to lesser characters played by lesser actors. He’s immensely likeable in the film, and Samy Burch’s adaptation of Arthur Schnitzler’s novel gives him ample room to maneuver through every scene without seeming to hog screen time or space. And his co-star Lee gets a lot of mileage playing the salon ingenue who assumes different personas with every costume change. (Her contribution to a public poetry reading is a knockout vocal rendition of Brecht/Weill’s “Surabaya Johnny.”) Late Fame has a timeless Manhattan feel that complements Dafoe’s poignantly moving poet. When Ed gets up and reads his one great 70s Manhattan love poem to a roomful of Village residents, he nails it. Ed, Gloria, and Jones’s movie are the real deal, the keepers.

Blue Moon: Richard Linklater: 2025:US, Ireland: 100 minutes

Ethan Hawke is NYFF’s Renaissance actor. Year after year, your critic has watched Hawke get better and better, building his chops and his craft through memorable stage productions of The Coast of Utopia, Hurly Burly, Clive, True West, and Hamlet. On television, Ethan’s currently takin’ a beatin’ and keepin’ on tickin’ in eight rowdy episodes of The Lowdown.

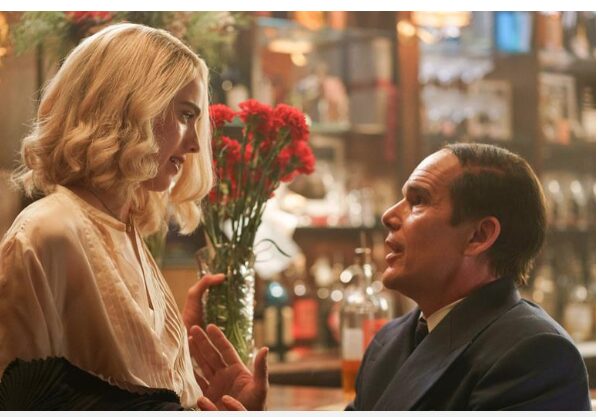

But it’s many Manhattan festivals through the years, including but not limited to NYFF, that have showcased an actor who’s become a marketable star, taking hold with a permanence that’s approaching the legendary level. Paul Schrader pulled a career-altering performance out of Hawke as an upstate New England pastor dying of depression, alcoholism and cancer, in First Reformed. Richard Linklater stretched Hawke further in the “Before” trilogy with Julie Delpy, especially Before Midnight, and grew him through twelve consecutive Texas summers of shooting as Ellar Coltrane’s dad in Boyhood. Pedro Almodóvar cast Hawke as a gay cowboy in Strange Way of Life, a half hour exercise that began to redefine what we think of as a feature motion picture. And now Hawke delivers the career-topping performance that ought to win him an Oscar nomination or more, as Tin Pan Alley’s Lorenz Hart, the show-biz composer dandy of tunes you’ll hum forever, including “Manhattan,” “Lady Is A Tramp,” “My Funny Valentine,” and “Blue Moon.”

Look at the pictures here. Hart was just five feet tall. It almost looks like Ethan has shrunk, in the tradition of José Ferrer playing the 4’8” painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec in Moulin Rouge on his knees, or Robert De Niro bulking up 60 extra pounds to play Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull. Part of the illusion is Ethan’s tight-fitting suit and combover wig atop his shaved head. It’s also the actor’s sheer craft in making less of himself, while putting away a fifth of hard liquor and unloosing an endless flurry of monologues as Broadway’s motormouth lyricist. This all takes place immediately after the opening night of Oklahoma on a wintry night in 1943, at Sardi’s. The rave reviews pour in on the show and its score, which was written by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, not Rodgers and Hart. The abandoned writer can’t believe New Yorkers who “live every day with a sense of doomed hopelessness” could possibly embrace lyrics that celebrate “corn as high as an elephant’s eye.” Even with his face on a 33-cent first class postage stamp, Hart senses he’s on his way down and maybe out. And so he drinks.

Sardi’s bar is where Hawke spews invective for nearly 99 of 100 minutes of Blue Moon. It’s six months before the revival of A Connecticut Yankee would open, with tunes penned by Hart, when Lorenz would fall down (likely in an alley off 8th Avenue), dead drunk in pouring rain, dying days later of pneumonia and chronic alcoholism at age 48. That’s the movie’s brief and ominous opening, which will clue you Blue Moon won’t end well.

But inside Sardi’s bar, all is warmly cocooned and cushy. Among the ensemble cast gathered to play off Lorenz are Eddie the bartender (Bobby Cannavale, turning it way down), cast as the sympathetic enabler, first resisting, then pouring Lorenz every drink he demands. At the piano is Knuckles (Jonah Lees, fine), keeping The Great American Songbook rolling, mainly as a melancholy rug under Hart’s rants. The female interest is Elizabeth, a barely 20-year-old Yalie who’s the daughter of a Theater Guild board member—she’s a heartthrob for Hart who’s a self-described “omnisexual.” Margaret Qualey, who’s climbing fast in screen roles, plays her with punchy vulnerability.

Hart gets his picture snapped by Weegee (John Doran), the tabloid photog with a fondness for dead celebs. He’s briefly silenced by Richard Rodgers (an earnest Andrew Scott), who demands sobriety through any future collaboration. E.B. White (Patrick Kennedy, dry and droll), turns up, probably thinking about the quintessential Manhattan essay, This Is New York, he’ll soon write. There’s even a smart-ass 13-year-old in the room, taunting Hart, nicknamed “Little Stevie” (Gillian Sullian), an obvious tease on Stephen Sondheim. Hawke wraps them all around Hart’s wet-brained little finger, relishing every line of the exceedingly barbed, witty, and knowing screenplay by Robert Kaplow, who dug deep into Hart’s history and correspondences.

The ultimate irony of Blue Moon, which Hart would surely have raised a glass to, is that Linklater’s splendid recreation of Sardi’s glistening tony bar with its rich Manhattan swells, wasn’t shot on a sound stage in or near New York City, or Hollywood… but, of course, where else, in Ireland.

Jay Kelly: Noah Baumbach: 2025: UK, US, Italy: 132 minutes

George Clooney is NYFF’s Renaissance movie star/statesman.Let’s start by reminding ourselves that back in June, Clooney was the guy who made it possible for America to watch a free live telecast of Good Night, and Good Luck on CNN, the same night a packed Broadway theater audience was paying up to $800 a ticket to watch it in person. Clooney played the lead role of Edward R. Murrow, the fearless CBS newsman who took on the 1950’s Commie-obsessed senator from Wisconsin, Joe McCarthy. Twenty years ago, Clooney directed the same play as a movie, playing Fred Friendly, Murrow’s producer of integrity at CBS, a television network which once was a news beacon of incorruptible independent inquiry, but today is inexorably bending another way.

Clooney’s career has been as diverse as any actor/producer/director on screen. Besides the title character Jay Kelly, he was Batman in Batman and Robin, and Michael Clayton in Michael Clayton, in which George as Michael beats a bad gambling habit, a car-bomb assassination attempt, and even the nasty opposing lawyer (Tilda Swinton, evil, evil). He’s won two Oscars, for best supporting actor in Syriana and as co-producer of Argo. The man has never stopped working since playing the dreamy Dr. Doug Ross during 108 episodes of ER.

Jay Kelly pairs him with director Noah Baumbach, who’s becoming an expert in directing movies (Marriage Story, a 2019 NYFF critic’s choice) about married showbiz celebs whose kids are left in the lurch like collateral damage. In Marriage Story, it was Adam Driver playing an off-Broadway director focused on his big break. Here, Baumbach gets your instant attention and awe with a choreographed-to-the-teeth opening of a crime drama movie set (8 Men From Now, a sly riff on the bargain basement western 7 Men From Now) fitting itself together like puzzle pieces. The photo shows the pieces locked in place, framing Jay for his end-of-life scene slumped on the ground, with the old Pepsi sign lit up on the far side of the East River, hilariously misplaced under a Manhattan bridge that doesn’t exist there. It doesn’t matter. Jay immediately grabs you acting his confessional farewell, and it’s poignant and moving and crew members are dabbing their eyes. Then Jay asks for another take.

Jay Kelly is a kinder, gentler, infinitely more relaxed version of the bitter and abrasive Marriage Story. Credit Clooney’s unending charm and empathy to all, especially when he’s behaving like Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley, whose life credo was “it’s better to be a fake somebody than a real nobody.” Highsmith’s definition lines up closely with the opening title Baumbach and co-writer Emily Mortimer post from Sylvia Plath, that “it’s easier to be somebody else, or nobody at all.” Or maybe Baumbach goes softer here than Marriage Story because Mortimer’s a new writing partner.

The movie’s premise won’t distress any home viewer. Jay’s been invited to the Tuscany film festival (one he used to turn down) to receive a lifetime achievement award. So he asks his neglected older daughter (Riley Keough) and younger college-bound daughter (Grace Edwards) to join him. No way. (The plot echoes another fest selection, Joachim Trier’s Sentimental Value, in which an aging movie director played by Stellan Skarsgård begs his neglected stage actress daughter to star in his next movie.) Jay’s younger kid, who’s decided to take a Euro holiday with friends, finds herself embarrassingly stuck on the same train to Tuscany as dad. And as usual, her father is surrounded by his everyday protective entourage —the doting manager Ron (Adam Sandler), harried publicist Liz (Laura Dern), hair/makeup lady (Emily Mortimer herself), plus security. These are Jay’s paid shields against everyone critical of him— his father (Stacy Keach), a late director/mentor (Jim Broadbent), a former acting class buddy (Billy Crudup), Ron’s kids and frazzled stay-at-home wife (Greta Gerwig). Jay Kelly boasts a super keen supporting cast, capably serving as Jay’s present or past guardians against his pesky antagonists. And Jay has a kind word for each and every person, friend or foe.

The difference today is that Clooney has learned to do failure and remorse with pinpoint accuracy. Michael Clayton was in many ways his warmup for Jay Kelly. As Michael, law firm clients regarded him as something of a miracle worker, but Michael admits the truth—he’s “a janitor sweeping up other people’s messes.” Even when Clooney played a despicable corporate suit, as in Up In The Air (2009),flying around the country as a hired job killer, axing thousands of downsized execs, we give him a pass. Clooney’s endless optimism and casual nonchalance in that picture somehow persuade us that his only motivation in delivering misery to a lot of people is building himself a million miles in frequent flyer miles. Clooney’s a major force today in American culture, with an expanding skill set that just won’t quit.

In Jay Kelly, a cautionary tale that’s also a supremely entertaining outing, Jay answers the question first posed by Budd Schulberg’s classic 1941 novel of Hollywood, What Makes Sammy Run. Jay’s memories, as he says, are entirely movies. And what made Sammy run, no less than Jay Kelly, was chasing after all the material success and adulation those movies could lay at his feet. As well as his fear of losing it all.

No Other Choice: Park Chan-wook: 2025: South Korea: 139 minutes

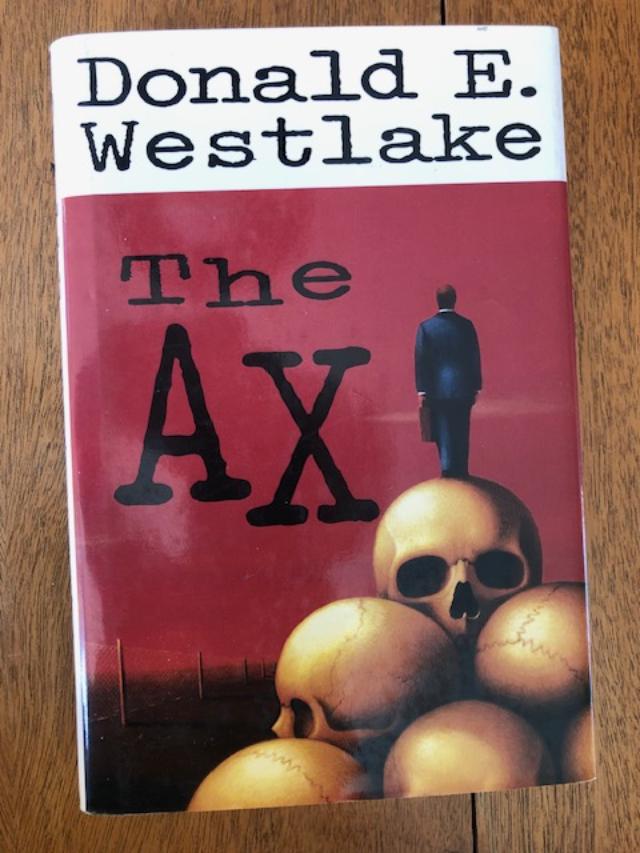

The backstory: In the early years of this century, Donald E. Westlake, among the finest post-war crime writers of the 20th century, guested this teacher’s course, “Killer Writers” at The New School. Don had written 24 hardboiled Parker novels from 1962-2007, alternated with delightful Dortmunder capers the same years. He’d gotten an Oscar nomination for adapting Jim Thompson’s The Grifters, and he’d sued Jean-Luc Godard (and won) for stealing one of his Parker novels (not to mention casting Anna Karina as Parker). But Don wrote non-character books, too. The novel that classes always read— it was Westlake’s favorite and he dedicated it to his dad— was The Ax. It’s a shrewdly conceived revenge novel, laced with wicked humor, of what happens when a middle-aged research chemist and middle manager at a paper company loses his job and retaliates.

In Westlake’s novel,the unemployed paper manager—he’s a good husband and dad to two teens—has sent out resumes for two years without any luck. He quietly watches the guy who’s replaced him and advertises the job’s qualifications with a post office box number in paper magazines. Then he identifies six candidates including the present job-holder, sets out to track each one down, and kill them all.

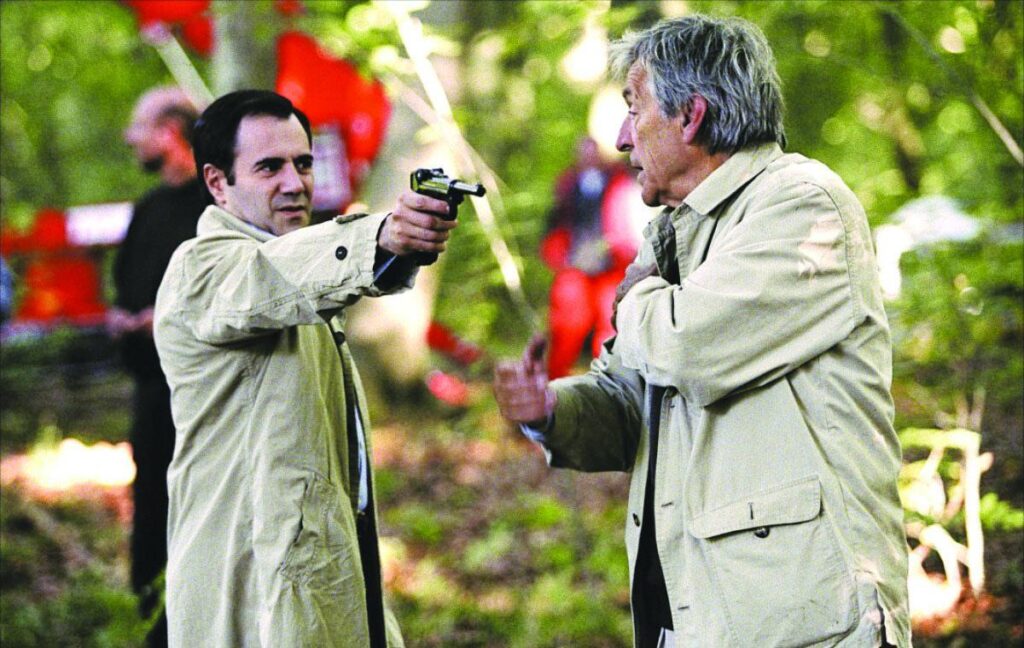

The world class international director Costa-Gavras (Z, State of Siege, Missing) adapted The Ax to vivid screen life twenty years ago as Le Couperet. It starred the versatile, bouncy José Garcia as the embattled job hunter and serial killer, Bruno Davert. Le Couperet premiered at the 2005 Tribeca Film Festival and Don and Costa-Gavras were there, arm in arm, confident their picture would find a distributor—plus plenty of sympathetic Brunos and their families who were being axed by soulless corporations from coast to coast.

Editor-in-Chief Gary Crowdus of Cineaste magazine interviewed Gavras (Vol. XXXIX, No. 1), who offered key insights on Westlake’s novel and his film:

“The Ax is two movies: the first, which shows that Bruno has lost his job and reveals the problems that creates for him and his family, is completely realistic. In the second part, when he starts to kill people, the audience knows it’s not realistic, it’s a cinema game. At the end, when the police arrive, I’ve seen audiences frozen in fear because, they told me, ‘We don’t want him to be caught.’ So even though Bruno has killed five people, it’s clearly a game between the film and the audience, which understands and sympathizes with the character.”

Yet Le Couperet never found an American distributor. Why? Was it because the killer gets away with all his murders and gets his job back? Was it because the killings have an edge of humorous blunder, like a bulldog popping up in a car window, blocking the killer from pulling the trigger of his German Lugar at a job competitor in the next lane? “The audience gasps and laughs at the same time,” Westlake wrote the instructor and told classes. “The movie is terrific, faithful without being obsequious.” Alas, the hybrid crime movie made from his hybrid crime novel never found a distributor.

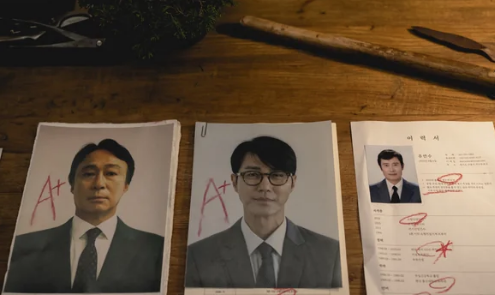

Park Chan-wook’s remake: The first thing to note about No Other Choice is that it has a US distributor, Neon—among the smartest distributors in the world today. It’s the New York-based company that bought Bong Joon Ho’s gleeful and gory Parasite and helped it win the Oscar as Best Picture. Neon’s releases have won six Palme d’Ors in a row (including this fest’s It Was Just An Accident). Pause this review now and watch their snappy trailer for No Other Choice. Moving the setting from U.S. soil to South Korea works instantly— it’s the same industrial setting and plot. But the pacing is more urgent, more colorful. What you can’t tell from the trailer is that at least one scene is over-the-top grotesque, as is much of the humor— almost exactly like Parasite. The second thing to note about No Other Choice is that co-writer/producer/director Park Chan-wook, who wanted to remake Le Couperet for twenty years, has dedicated No Other Choice to Costa-Gavras. The movies are linked at the hip.

This prompts another question worth considering: When did mayhem in the movies get the blessing of art cinema audiences? It certainly started before Parasite. This viewer traces it back to 2006, three years after Park bludgeoned audiences with his film Oldboy. In the 2006 New York Film Festival, Guillermo del Toro introduced his closing night Pan’s Labyrinth to a packed house with the warning “If at least 100 of you don’t walk out of my film, I will have failed in my mission as a filmmaker.” And sure enough, when teeth started getting ripped from the jaw of some innocent with pliers, over 100 patrons bolted Alice Tully Hall. Most remained. This wincing tooth extraction gets repeated in No Other Choice, but it doesn’t seem to have fazed patrons at the Toronto International Film Festival, where it won the fest’s Audience Award. It elicited a few groans from the New York press watching No Other Choice, but no one walked out. A lot of otherwise erudite moviegoers have become Fangorians.

In No Other Choice, the research chemist You Man-soo (Lee Byung-hun), his wife Miri (Son Ye-jin), their two lovely children and two golden retrievers live quite comfortably—dad’s original childhood home. But when the paper company he works for suddenly downsizes, You Man-soo is fired with only three months’ severance, and everything falls apart fast. The tennis lessons and Netflix subscription are first to go, then the dogs, and finally the couple has to sell their cherished house and move to lesser digs. Man-soo sets about to get his job back by exacting the same retaliation as Don Westlake and Costa-Gavras’s deposed manager.

What’s changed is how the viewer processes these two filmic versions of The Ax. It’s partly their tonalities of violence and often ghastly humor. It also has to be the context of how the adversary has changed. In 2006 it was Big Business dumping workers on the street. In 2025, the government and A.I. are taking over that leading role. You may or may not experience feelings of fear and dread as you view No Other Choice. This viewer did, and it didn’t happen back in 2006 with Le Couperet.

Count on Neon to get this Ax seen by the world.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in DOC NYC, America’s largest documentary festival, November 12-20.

Regions: New York City