DOC NYC Nov 10-18 – Critic’s Choice

Looking for a career path in film, journalism, the art world? Senior critic Kurt Brokaw advises three keen directions from America’s largest documentary festival

It was once possible to view everything in any of New York’s six major film festivals, sometimes even before they opened. Curators limited their selections to 25-30 features and a handful of shorts. Your critic gladly sat through most everything with other press/industry, usually in advance theatrical showings a week or two (or more) before red carpeted Opening Nights. No longer.

This 12th annual edition of DOC NYC, for example, showcases over one hundred and twenty (repeat, 120) feature-length docs among over 200 (repeat, two hundred) films and dozens of events. Its screening venues have expanded from IFC in Greenwich Village (5 screens) north to Cinepolis Chelsea (9 screens) and the School of Visual Arts (2 screens) on West 23rd Street. Only a fraction of total films were previewed theatrically in advance, while scores more (though not all) became available on a virtual press portal ten days ahead. Many of the pictures shown in Manhattan theaters Nov. 10-18 will be available online across the U.S. Nov.19-28.

This viewer, forever trying to be a valued resource who “views it all so you don’t have to,” faces the daunting task of pre-selecting from pages and pages of available features and shorts. But pre-selecting what? If you can choose only one slice of a pie with seemingly unlimited flavors. which slice should you take? Opening Night, Centerpiece, Closing Night selections? NYC, U.S., International films? Award winners from other tests? Work by documentary legends and luminaries? Profiles of singular individuals? Personal journals of discovery and transformation? Docs on jocks? Shorts? Student films? The last two categories alone are bursting with 70 chosen shorts and 39 student selections.

The mind boggles. As DOC NYC’s theatrical venues open to masked-up patrons with proof of Covid-19 vaccination, one peruses the mountain of available subjects, searching not for the perfect handful of across-the-board documentaries, but perhaps the most useful criterion for a reviewer’s readership. So for this viewer at The Independent—for decades a journal dedicated to hard news for aspiring and working indie filmmakers—a fresh question arises: What docs might have the greatest impact today for students who are drawn to (and are studying and may be preparing for) career paths in film, publishing or the art world? If that seems a fair going-in agenda in examining this 200+ film festival during a fall semester worldwide, here are three outstanding electives:

Film, The Living Record of Our Memory: Inés Toharia: Spain/Canada: 2021: 120 minutes

There’s no better way to speed up your learning curve on the art and craft of filmmaking than to immerse yourself in the passion of film preservation and restoration. Your outside homework can start with critic’s choice reviews of Celluloid Man (New York Film Festival, 2012), a definitive biopic of P.K. Nair, the savior of over 8,000 films made in India, and our Tribute to Jonas Mekas following the passing of Manhattan’s most committed preservationist and co-founder of Anthology Film Archives.

Mekas and Nair both receive prominent attention in this exhaustive international survey of the labors-of-love trying to hold onto the disappearing roots of a medium. Director Toharia is a Spanish documentarian and archivist as well as a founder of the Western Sahara International Film Festival. Perhaps sensing this may be the final word on the decomposition of 35mm nitrate film—not to mention the problems confronting video tape as well as digital—she seeks input from “the backstage people”—committed experts in Australia, Tanzania, Buenos Aires, Thailand, Norway, Cuba, Africa, Libya, Japan, Taiwan, Bologna, Mexico, Nigeria, the Sudan, the Philippines and other far-flung lands.

Not all are unknown. Martin Scorsese has championed preservation ever since he made the decision to shoot Raging Bull (1980) in black-and-white,fearing color stock would turn to magenta over time. Documentarian Bill Morrison (Dawson City), the late Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami (Certified Copy), cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (Apocalypse Now), Costa-Gavras, director of Z and director of La Cinematheque Francaise, plus historian Kevin Brownlow (The Parade’s Gone By) are all familiar names to cinephiles.

Everyone is facing shared concerns that half the nitrate-based films made everywhere from 1900-1955 are decaying and decomposing, and that nearly 80% of all silent films have fallen to dust. Home movies on Super 8 were kept forever, but once a commercial feature had its run and the valuable silver nitrate was extracted from its film stocks and sold, few pictures were perceived as having any commercial value. Nitrate stock is also highly flammable; spectacular fires have destroyed a sizable portion of movies, and for years Mexico’s largest collection of feature films was stored above a gasoline station.

The memories of much of the world’s population are no longer viewable because they no longer exist as moving images—except, here and there, where the one surviving pictorial element may be a duped negative, purloined overnight and often returned to the editor’s workbench by dawn. (This is the earliest form of what we know universally today as film piracy, and why Warner Bros installed three security guards at a press screening of Dune at another festival just weeks ago, to insure no one was camcording the movie.) A common attitude in Hollywood in the 1930s was “Who cares if a Fred Astaire movie is lost, he’ll always make another one.”

And so the work of rebuilding a nation’s history through its cinema is an endless pursuit. And a frustrating one: Mold, high humidity, the destabilization of film grain, limited resources, uncaring governments all work against the preservationist. Highly developed countries like the U.S. and Japan have the luxury of hoping that a lost Alfred Hitchcock silent feature, The Mountain Eagle, or an early silent feature starring Japan’s matinee idol Sessue Hayakawa, will one day turn up. But in the Dominican Republic, the oldest preserved film was made in 1988.

And it’s not just theatrical entertainment that’s lost. Toharia gives attention to a massive universe of industrial, educational, institutional, and commercial films that contribute to the definition of a society. The Shoah Foundation has diligently sought out and preserved tens of thousands of oral testimonies from genocides in many countries. The entire history of the Olympics has been pieced together. For years there was more film shot in Detroit—much by the premiere Jam Handy organization—than in Hollywood and New York combined. The world renowned Ridley Scott,whose “1984” Superbowl spot introducing Macintosh still has the highest recall of any TV commercial in history, recalls reorganizing an entire shoot for another product around a sudden change in natural light.

And the future? Why worry, you ask, when a retrospective venue in New York, Boston or Los Angeles brings in 4K restorations of your favorite movies? “Digital is not preservation,” warns Vittorio Storaro. Just as YouTube is not an archive. Sam Gustman, the chief technology officer of USC’s Visual History Archive, spells out the longevity factor: “You have 50 years before you see age-based deterioration in film, 20 years in video tape, 5 years on HD drives, 3 years on Beta tape, 2 years on DVD. The faster it’s developing, the faster it’s rotting.” Preservation’s next frontier may be in synthetic DNA, already inaugurated to protect Cathy Freeman’s Gold Medal win in the 2000 Australian Olympic Games.

For this viewer, there are two seminal moments in Film, The Living Record of Our Memory. The first concerns British director Ken Loach, who continues to film in 35mm and needed a particular coding tape, which Pixar—of all companies—was pleased to provide him with. It seems the codes on film stock have to match the codes on the host projector, or the movie won’t play. This brought to mind a screening several years ago of a brand new drama from a major American distributor, at the Walter Reade Theater, arguably the best theater in New York City to view anything. For some reason the codes on the print didn’t match any projector in the Walter Reade’s booth; no back-up print was brought along; and so the entire audience, after waiting and waiting, was asked to get up and march across the street to the Munroe theaters, where the codes on one projector had been hurriedly tested against the print, and—eureka!—matched up. Ah, modern technology.

The second defining moment in Toharia’s doc is a happier one. The Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan’s print of the 1943 Casablanca was made from the oldest existing materials on this classic drama, which starred Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman. The experts will tell you if you watch this print, “it’s like you’ve never seen Casablanca before.” Says Katie Trainor, Film Collection Manager at MoMA: “It’s my ‘Starry Night’ by van Gogh. I do believe that film is comparable as an art form to the paintings and sculptures in this building.”

Let’s give Ken Loach the last word on Toharia’s enthralling documentary: “Cinema is light…and enlightenment.”

Storm Lake: Beth Levison and Jerry Risius: USA: 2021: 85 minutes

“For editorials fueled by tenacious reporting, impressive expertise and engaging writing that successfully challenged powerful corporate agricultural interests in Iowa.”

—The 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Writing to Art Cullen and The Storm Lake Times

The newsman is typing away on his desktop, and he’s grumpy. He’s on deadline, “and everyone is working hard but me. And it’s costing me money. The Storm Lake Times weaves the fabric of the community in large ways and small. We publicize the fundraisers for the visits of illness. We champion lake dredging. We promote Buena Vista University…”

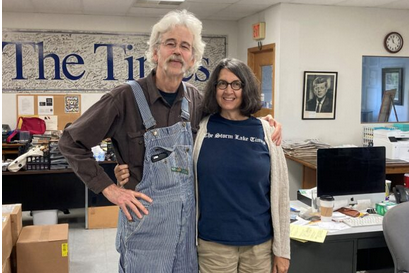

He steps outside for a cigarette. His mop of unruly white hair could use a trim. This “Editors Notebook” editorial is not going easily, because Art Cullen is trying to rustle up more subscribers, and more advertisers. He’s wearing a fundraising hat, not the usual role for Pulitzer Prize winners. The newspaper his brother John founded in 1990 once drew a crowd, but its circulation has dropped to around 3,000 and it now publishes twice a week. Cullen is keenly aware one in four U.S. newspapers has shuttered in the last 15 years. It’s March of 2019 and various democratic contenders for president are coming to Storm Lake for a Q&A forum Cullen will moderate. “More people care more about their garbage being picked up, about who’s getting married or buried, than whether Elizabeth Warren’s in town,” the journalist mutters.

Beth Levison and Jerry Risius’ modest, engaging documentary doesn’t ask for your sympathy. Just the opposite—it’s as winning a recruitment doc for small town American journalism as you’ll see likely see anywhere. Located an hour and and a half drive from the Minnesota border, Storm Lake is like many Midwestern towns that started and stayed Republican for decades, more recently welcomed a sizable influx of immigrants, and have suffered COVID setbacks further eroding a mom-and-pop Main Street that still matches the cover of Sinclair Lewis’ 1920 novel. (Complete with a Better Times Cafe.) The movie’s core concept is how an owned-and-family-operated newspaper stubbornly survives.

John and Art, his wife Delores (reporter and photographer), their son Tom (reporter), plus sister-in-law Mary (recipe columnist), lead a tiny staff of ten. John, who’s on social security, works for free. Peach the newshound hangs out. There’s a rabbit who likes pizza. It’s usually a break-even operation at best. The editor isn’t the paperboy, but he and John regularly load fresh press runs into their cars and deliver to the local convenience stores. Not all of Storm Lake’s ten to fifteen thousand residents agree with the paper’s editorial positions, but most regard the Cullens as bone-honest, home town folks who care about their neighbors.

Both brothers are painfully aware that torrents of rain are pushing spring planting clear into June, that Iowa is getting not just wetter but warmer, that as family farms wilt, the vital advertising from farm supply and feed stores dries up. The newsmen are attuned to a population “that expects its news with its breakfast on Facebook, and that’s not how you sustain a democracy.” Most of Storm Lake Times’ subscribers work in agriculture, and Art Cullen is staking his future (he’s 64) on a rural readership that desperately wants to hold onto its farms, as well as a partly undocumented urban community that Art acknowledges is “living with fear.”

Tom, a seasoned reporter who’s trying to help his parents hold onto the paper, voice-overs part of the narrarive, as does Art. “The prospect of the newspaper not being around terrifies me,” Tom admits, especially as there’s a Spanish competitor, La Prensa, building share-of-voice in the Hispanic communities of Central and Western Iowa, under editor Lorena Lopez. The exchange of stories in English and Spanish between papers is advanced. The Times has clearly boosted its coverage of people of color— a major story headlined “High Court Might Strike Down Dreamer Protection” is side-by-side with an equally prominent local story (with large family photo) announcing “Friends Support Alvorez After Kidney Transplant.” Storm Lake’s elementary school, in which half the students are native Spanish speakers, has started its first dual-language program, only the 7th in the state.

As Covid hits hard in the spring of 2020, we watch color photos changing to those who’ve perished, with headlines like “Shock of virus death felt around Storm Lake,” sub headed “Gallery members try to support Barahona family.” By the end of 2020, a GoFundMe campaign to keep The Storm Lake Times from collapsing had $28,275. The paper joined forces with La Prensa and two other family papers to form the Western Iowa Journalism Foundation.

A Note Of Hope From Art Cullen

So what’s happened since Beth Levison and Jerry Risius turned off their cameras? We were curious, so The Independent reached out (11/2) to editor Art Cullen for a heads-up, and also any advice he’d give to students contemplating careers in publishing. Amazingly, Cullen answered our queries in less than an hour. The news is encouraging:

“After hearing me on a public radio Fresh Air interview connected with the documentary, an immigrant who made it big out in California mailed us a fat check that should see us past the first quarter of next year (the first quarter always being the most dismal in every way.),” writes Cullen. “We are in productive talks with some of the interests that have disrupted our business model, including leading Silicon Valley tech foundations that could be very helpful to legacy print publications in making a digital transition. Circulation is steady. Advertising has picked up since 2020. We broke even several months this year. I think we have hit bottom, and the only way to go is up.”

Cullen’s advise to students considering work in journalism is profound: “Wherever there is failure there is opportunity. Creative destruction, or something like that. Where publications fail on their own merits, as they do, young people with digital know-how can provide those news deserts with new information products that were better than before. I think there is tremendous opportunity for young people to help legacy organizations like ours to make a transition to a digital business model that old farts like me don’t quite understand. I still don’t trust TikTok and don’t use Instagram. People will always seek out the truth, and there has to be someone there who can make a buck from telling it.”

The above paragraph may be worth printing out and taping next to your laptop screen.

The Art of Making It: Kelcey Edwards: USA: 2021: 97 minutes

Maybe your major or your side hustle isn’t in film or journalism. Perhaps what you’re longing to be is a fine artist, showing your canvasses in leading-edge galleries or, one day, in the world’s great art museums. Assuming you could get in, and providing you commit to shouldering a mountain of tuition debt, should you try for an MFA from a frontline arts university? Could this better your chances of the right curator spotting and validating your work? Yes/no/maybe? What if you’re Black, queer and/or female, and have faced closed doors, disinterest and hostility your whole life?

Kelcey Edwards’ of-the-moment doc on the intersections between innovative, urgent new talents and some of the art world’s highest paid gatekeepers may be instructive. She’s said the smoldering question of her investigation is “how come the only people who can afford to be creative are already wealthy?” A scene upfront is a stunning example of how artists and galleries are challenging the ultra rich: We watch art dealer James Salomon unpacking and installing life-size sculptures (from 3-D scans) of Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos as warriors on horseback, alongside a crowded, busy collage of struggling, agonized figures “representing the unemployed” under them.

Helen Molesworth is the on-camera author and critic who monitors this enormous gulf between young artists who display unique brilliance but have zero power in the marketplace, and classy dealers who play to the elite and have all power. She’s the former head curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, and may have been dismissed for objecting to MOCA as “a white space with no person of color on the board.” Molesworth pulls no punches: “Being in the art world is like being in a small, sectarian cult, one with its own belief systems and its own social practices and mores,” she explains. “We talk in code, we dress a certain way, we’re very identifiable to one another, but we are not an open field.” It won’t surprise you when she laughs that “museums are an 18th century idea in the 21st century. If they’re serving the public, which public?”

This doc leans to those empathetic museums and disruptive dealers attuned to what Ralph Ellison once described as “voices on a lower frequency.” They’re often new artists of color who may have flunked out of art school but are doing work that Molesworth applauds as “bohemian, radical and totally cool.” These innovators, plus the artist/professors who believe in them and the dealers fighting to make them visible, are the secret sauce of The Art of Making It. One key ingredient is “making art for audiences that don’t exist yet.” You may sense you’re in the right place in Cesar Garcia-Alvarez’ alternative nonprofit art space in Los Angeles called The Mistake Room.

Today’s success matrix doesn’t recognize that. The traditional process ideally propels a budding talent from a graduate art school to small gallery to mid-size gallery to mega-gallery to big collector to major museum. Three out of four major museum acquisitions are from big collectors. One in five artists in top Chelsea galleries have an MFA from Yale. Nearly everyone follows the grants, the residencies, the money.

One CEO who walks into the crosshairs of director Edwards’ inquiries is Marc Glimcher, president of Pace Gallery, headquartered in lower Manhattan (with nine international locations). Glimcher is a supremely self-confident host who speaks with pride of the vast Pace empire, noting that his favorite volumes in Pace’s walls of art books are “The Complete Collection of Vincent van Gogh’s Letters” to Cezanne and other art titans of the 19th century “and especially his brother Theo.” It’s a priceless moment that vividly illustrates the aesthetic and the marketplace etched above by Ms. Molesworth.

The Art of Making It soars when it concentrates, as it often does, on the concepts and the process of making boundary-breaking art. JR and Banksy already have their own feature docs. The headline makers here, as always, can be the most unusual—like Ai-Da, a cunningly attractive robot with augmented speech, devised by an English gallery owner, who recently was detained by Egyptian customs for 10 days (because of the modem and cameras in her eyes) before continuing to her role as a mummy in an exhibition in Giza. Another vivid outlier is Hilde Lynn Helphenstein, who’s rebranded herself as “Jerry Gogosian” (a mashup of art critic Jerry Saltz and mega gallerist Larry Gogosian), deciding to keep the name because she found her work being taken more seriously as a male.

But the picture really belongs to preemptive new ideas—shifting the Black Gaze from literature to portraiture, streaming one’s own art online and bypassing the gallery scene altogether, planning ways to give royalty payments to the people who posed for the artist’s brush, often for little or nothing.

The future also belongs to artists Chris Watt and Gisela McDaniel (each pictured), plus Felipe Baeza and Jenna Gribbon. A few attended big name schools, though Chris was tossed out of Yale. A few apprenticed big name artists like Gogosian and Jeff Koons. Several including Chris have worked endless hours as baristas and bartenders. Gisela offered her paintings on the sidewalks of New York, which artists and vendors of written matter have the legal right to do without licenses. Both Gisela and Chris have debuted successful solo shows.

If you’re studying art, expand your knowledge (and your hopes) with this doc.

A First For Two Shorts

Two critic’s choices from June’s Tribeca Film Festival have migrated over to DOC NYC: Coded and The Queen of Basketball. This is the first time two such honors have happened. On one other occasion a short from the Tribeca fest (Curfew, a Soho drug tale with a heart) moved uptown to NYFF, became a critic’s choice not once but twice, and went on to win the Oscar in 2012. If you haven’t read this journal’s reviews on these two DOC NYC shorts, check the linked Tribeca review.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in The New York Jewish Film Festival in January, 2022.

Regions: New York City