New York Film Festival, Sept.30-Oct.16

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw celebrates 60th festival favorites—plus an appraisal of a lifetime in the dark at Lincoln Center

Above is Nan Goldin’s photo that’s become the poster for this 60th NYFF. Talk about a picture being worth a thousand words. It celebrates movies as they once were in the 1960s (and long before), when Irving Shulman’s 1947 The Amboy Dukes was the coming-of-age novel for NYC bonehead teens and wayward young adults. Youths on Amboy Street in Brownsville brought their six packs of Schaefer and jazz sticks (as marijuana was called) to local drive-ins, studying Tony Curtis and Julie Adams building their Amboy chops in City Across the River, a rude and inelegant B item. Drive-ins were the passion pits of our postgraduate youth of the 60s, and the New York Film Festival was the fancy new uptown girl. 58 years later, NYFF and John Waters (pictured) brought Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (a Marquis de Sade passion pit of its own) to an outer borough drive-in.

Here’s five more vivid memories—current and and going way way back in time—bookending 60 years of Fall seasons on New York’s Upper West Side:

- Noting that Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadness, a bleak satire of uber-wealthy society swells on a doomed luxury cruise ship (captained by Woody Harrelson as a lunatic Marxist), bears a squirmy resemblance to Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel, in which a gathering of the snooty rich find themselves trapped in an existential dinner party they can’t leave—NYFF’s Opening Night selection in 1963.

- Buying a reserved $4 ticket in the first four rows of Alice Tully Hall for years—then scampering back as the lights went down to Row M in center orchestra, the patron row, where an empty seat was always empty and waiting. Ticket prices for this 2022 fest ranged from $12 for members of Film at Lincoln Center to $125 for Alice Tully Hall’s opening night of Noah Baumbach’s White Noise, with Greta Gerwig telling a rapt audience that morning in a Q&A, “advertising flattens everything.”

- Confronting the late Joanne Koch, the visionary executive director of The Film Society of Lincoln Center, on the sidewalk after George Miller’s 1969 Mad Max, and demanding she explain how such a dystopian junk heap was ever selected for NYFF. Koch was just two years into her leadership role. Like fest director Richard Roud, she had an intuitive sense of what film-loving New Yorkers were poised to embrace. Neither curator had much patience for viewers who couldn’t move beyond Ingmar Bergman and Satyajit Ray. The fearless Ms. Koch would surely have celebrated Luca Guadagnino’s superior horror outing, Bones And All, NYFF’s first finger-lickin’ good tale of flesh-eating cannibals.

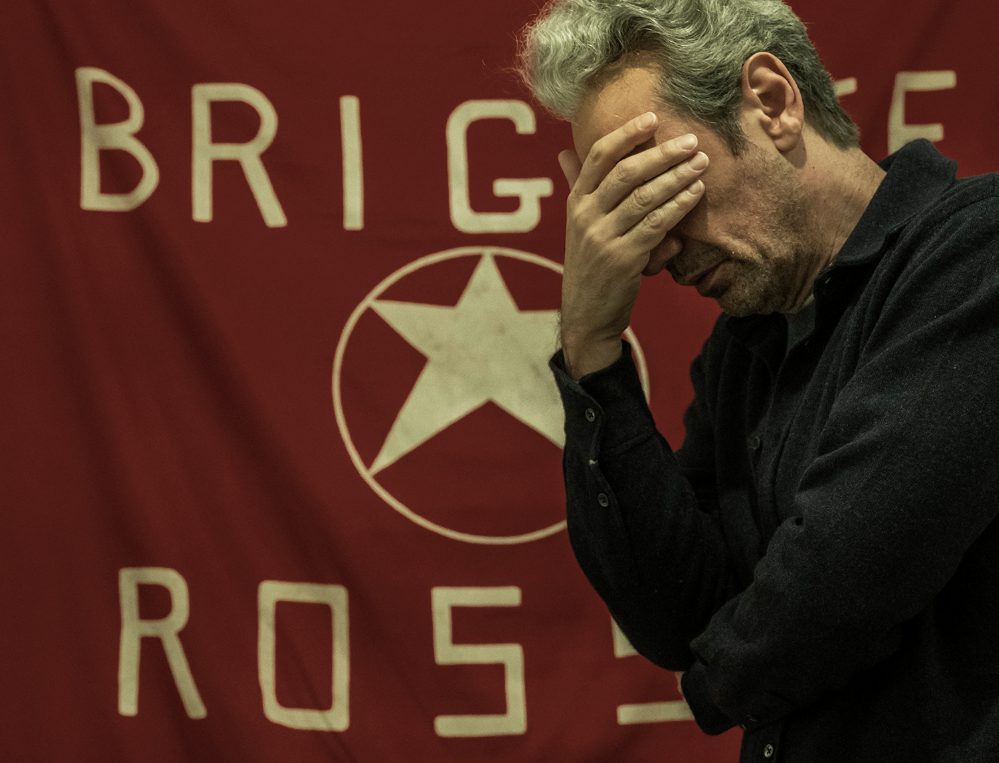

- Sitting behind Richard Peña at a public showing of Exterior Night, this fest’s 328 minute wild card by Italy’s master director Marco Bellocchio. Peña succeeded Roud, a Paris-based Europhile who was educated at the University of Wisconsin and ran NYFF (with his co-founder Manhattan-based indie pioneer Amos Vogel, for its first five years) for a quarter century. Peña, who’s fluent in many languages and did the most memorable Q&A’s with directors (using simultaneous translators), built his legacy opening cinematic windows into all corners of the globe. If you wanted to see what was playing in downtown Ethiopia, Peña was your guy. He ran the festival for another quarter century and would have loved quizzing Bellocchio on his latest, an epic crime drama based on the kidnapping and assassination of Italy’s prime minister, Aldo Moro, by a Communist hit squad, the Red Brigade. Bellocchio tells the story twice—first from the viewpoint of the Christian Democrat leader and the men around him including the Pope, and (following intermission) the same events seen through the eyes of the radical extremists who murder Moro. Five-plus hours on the big screen never moved so fast.

- Chatting up a slew of journalists, industry faces and festival volunteers (this one had 245 volunteers of all ages and stations in life) on who should replace the departing Eugene Hernandez, the festival’s fourth director. Wouldn’t you know, Hernandez is exiting to become the Sundance Institute’s fourth fest director. He’s a veteran journalist and digital wizard who once wrote for The Independent. Like his predecessor, screenwriter/director Kent Jones, Hernandez served a fraction of the quarter centuries logged by Roud and Peña. There’s precedent for a one or two-year appointment. This might tempt a world class director to pause a career in the service of a higher cause—lending cinematic leadership, name value and global impact to NYFF. Marty Scorsese or Spike Lee might be approachable, but heaven knows it’s past time to put a woman in charge of NYFF. This writer’s dream list is topped by (in alphabetical order) Jane Campion, Ava DuVernay, Laura Poitras and Sarah Polley. That something like this has never been done is exactly the reason to start the conversation today.

How The Independent Weighed In

Through its 30-year print history as a hard news source for indie filmmakers, no film reviewer was needed or wanted. But in 2010, the idea of a critic seeking out the best shorts along with narrative features and docs, struck a chord with former editor Erin Trahan. The shortest short would get equal space with the longest feature, in Manhattan’s six major annual festivals. What’s more, superior long and short films made in and around Manhattan would get some real love. Here’s a few examples, all NYFF selections of the past: Todd Haynes’s truly magical Wonderstruck, shot by Ed Lackman who’s been faithfully attending every NYFF showing for years … Rebecca Hall’s Passing, based on Nella Larsen’s ground breaking 1925 novel of the Harlem Renaissance … Haynes’s Carol, with Lackman’s luminous Super 16mm lensing brushing-and-combing Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara’s lesbian lovers in a velvety mid-century Manhattan … Ming of Harlem: 21 Storeys in the Air, Phillip Warnell’s astonishing documentary of an uptown resident who kept a 650-pound Bengal tiger (Ming) and a 7-foot Caiman alligator (Al) cozied in his apartment for years … and Shawn Christenson’s 19-minute charmer, Curfew, in which a Soho drug addict who’s about to slit his wrists takes a phone call from his sister, requesting he take her 11-year old daughter bowling (where, in a magical realism moment, the depressed uncle finds a possible path to recovery). We loved Curfew twice, first at Tribeca and then at NYFF in an encore showing, after which it went on to win the Oscar in 2012 as Live Action Short Film. (The Independent has spotted three other Oscar winning shorts long before they were reviewed anywhere else.) Read on to discover two possible shorts contenders in 2022.

NYFF has made both subtle and highly visible changes to increase its outreach beyond the Upper West Side. Film at Lincoln Center was once known as The Film Society of Lincoln Center. The experimental category “Views from the Avant-Garde” was changed to the less esoteric “Projections,” and now “Currents.” Enys Men, A Couple, and A Cooler Climate were assigned there or in “Spotlights.” Nobel Prize laureate Annie Ernaux headed a parade of free talks by Frederick Wiseman, Effie T. Brown, Alice Diop, Mia Hansen-Løve, Charlotte Wells, Joanna Hogg, Kelly Reichardt, Paul Schrader and Noah Baumbach. Filmmaker Cauleen Smith delivered the second annual Amos Vogel lecture. Perhaps the largest innovation was holding festival showings in all five boroughs of NYC, partnering the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema in Staten Island, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Bronx Museum of the Arts, the Maysles Documentary Center in Harlem, and the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens. Staff and audiences stayed masked up at all events snd screenings.

This 60th anniversary NYFF offered 120 features, arranged in half a dozen different categories. Except for curators who often see unfinished films months before they appear in finished form, viewing a couple dozen pictures two or three weeks in advance (which was once the film reviewer’s job) isn’t possible at huge fests like NYFF, DOC/NYC, and Tribeca. The viewing agenda is increasingly complicated by embargoes (no no’s on long-form reviews or, often, any reviews) until the picture’s opening. These are set by streaming services, studios and indie distributors, individual filmmakers, and even bricks-and-mortar theaters that invite critics to screenings. Many pictures at NYFF were seen the same day by reviewers and ticket buyers, making it impossible to objectively promote top favorites upfront. Here are critic’s choices–most will open this fall–grouped by common themes and followed by analysis of the best short and the best feature.

The Sweet Spots

White Noise is a savage and mostly hilarious sendup of 1980s consumer culture, hewing closely (often to the line) to Don DeLillo’s 1984 novel. Adam Driver is the history prof who teaches Hitler studies at a midwestern college, Gerwig is his community volunteer wife and mom of four (it’s a blended family, naturally). DeLillo’s Airborne Toxic Event, which has its modern day equivalent in every climate change you can name, is what spins their lives out of control. The fun is watching director Noah Baumbach throw a reported $80M of Netflix’ money—surely a bigger budget than indie directors ever hope to be handed by anyone but a streaming service—up on the screen with gleeful abandon. Noah stages spectacular train wrecks, car crashes and a traffic gridlock so long and so godawful, it supersedes Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend, his vivid 1967 preview of the decline and fall of western civilization. “Satire is what closes on Saturday night,” as George S. Kaufman once remarked, but Baumbach’s endless closing credits share the screen with a fun-lovin’ shoppers spree at the A&P. It’s a date-night movie made to order for urban sophisticates who need a break from all the ambulance sirens and COVID-testing tents along the Broadway beat these days.

Personality Crisis: One Night Only. David Johansen is one of a handful of Iron Men of rock still standing at 72. Martin Scorsese and David Tedeschi’s clear-as-a-bell documentary shows us why–highlights of a two-hour performance by Buster Poindexter, the rock singer’s alter ego as lounge lizard. Except Manhattan’s Café Carlyle is as pricey as it gets, and Buster’s band are subtle, nuanced musicians to die for. Ellen Kuras, who shot Lou Reed’s Berlin and knows how to frame rock legends, goes in real real tight, and David/Buster’s face, like Lou Reed in his final innings, is becoming a creased, majestic ruin. (He’s worlds removed from his bad boy days leading The New York Dolls through two teardown albums.) In Buster’s white-glove high society where there’s no mosh pit and everyone is quietly seated, you can actually understand all the words in a set list that’s shot through with wily knowledge and intimate regret.

One Fine Morning. With each film, Mia Hansen-Løve continues to expand and fulfill the promise of her Father of My Children, a deeply moving 2010 drama of an overworked indie movie distributor, a loving husband and father, who commits suicide. The inspiration for that film may have been the life and times of the producer Humbert Balsan, but Ms. Hansen-Løve is reaching into corners of her own filmic maturation with wisdom and aplomb. She’s especially good with children as well as aging parents, and in this outing Léa Seydoux plays a widower with a daughter who falls in love with a married dad, while caring for her aging father who’s slowly declining. It’s a ping ponging concept and in the hands of a less experienced director and an ensemble cast that’s not letter perfect, it would fail fast. But the director’s casting instincts and directorial choices are unerring and inspired. This is a movie you like, and like more and more. The sweetest spot of the fest.

Mothers in Extremis

The actresses in these three harrowing dramas are beyond fearless. All are caught in the tragedies of a child mutilated, raped or murdered. All have a factual basis. The three films reveal how women can bend to the most unimaginable events in their lives without breaking. Towering artistry lives here:

Till. Danielle Deadwyler plays the mother of 14-year-old Emmett Till, who takes a train from Chicago to rural Mississippi in 1955 to visit sharecropping cousins. He shows a white clerk in a general store his brand new wallet, a gift from his mother. In the picture section the manufacturer has placed a glam photo of Hedy Lamarr, a standard practice of its time. Emmett admiringly tells the clerk she “looks like a movie star.” This costs him his life. Director Chinonye Chukwu, fresh from her triumph of Clemency showing a Black female warden balancing the wheels of justice in a death-row prison, knows how to pilot this mother’s heartbreaking search for justice. She has to live through a rigged trial in which her son’s killers—the husband of the clerk and his half-brother–walk away free. The events are wrenching but you don’t turn away—a tribute to Chukwu’s expertise, Deadwyler’s measured performance, and, as her mother, Whoopi Goldberg, who finally gets to deliver a master class in parenting. Congress took its time—67 years—till a measure of justice was achieved with an anti-lynching act named after Emmett Till, passed this March. NYFF didn’t waste a minute, live-streaming a student showing of Till to cites outside Manhattan.

Saint Omer. Why would a Senegalese immigrant, Laurence (a mesmerizing Guslagie Malanda) sacrifice her 15-month-old daughter to a rising tide off the moonlit shores of Saint Omer in northeast France? Was it sorcery, as Laurence claims? Director Alice Diop, a recognized documentarian on immigrant communities, poses these questions in her fascinating debut narrative feature. She posits three viewpoints to consider in the courtroom trial that follows: The prosecution builds a convincing case that the mother, a scholarly student supposedly working on a PhD, is an unstable, pathological liar. The defense argues, with equal conviction, that a lifetime of oppression as a Black woman has permanently altered and damaged her DNA as well as her mind. The third viewpoint is the pivotal link that makes you, the viewer, into judge and jury—a compelling, Paris-based Black novelist and academic, Rama (Kayije Kagame). She’s come to witness the trial and puzzle out a book idea that ties the Media baby slayer myth into what she’s seeing. All this might read as a tortured exercise Diop concocted with one of her co-screenwriters, Marie NDiaye (who also co-wrote White Material, in which everyone on Isabelle Huppert’s coffee plantation is gradually slaughtered). But it’s not. It’s a daring leap of artistic imagination, made even more so by Rama’s mother being an immigrant and Rama herself being pregnant by a white man. When Rama locks eyes with the accused, who’s admitted letting her infant drown, the unasked question is whether her nightmare could happen again, not just in Saint Omer or Paris but anywhere a woman is captive in a white society’s unending racism. Saint Omer is the newest and most original variation on the oldest reality of victimization.

Women Talking. It’s not surprising writer/director Sarah Polley was drawn to Miriam Toews’s 2018 novel of the same name. Toews, who was raised as a Mennonite in Manitoba, Canada, based her novel around the lives of scores of women and girls in a similar colony in Bolivia who were anesthetized and raped by the men in their community. Toews shifted the location to a community in rural California, where her female characters have gathered their children and babies into a barn to decide whether to endure male savagery, fight, or flee. (We get a sense that it’s late 60s because the Mamas and Papas’ “California Dreamin” is playing somewhere.) The women have killed one attacker with a pitchfork, though it’s not shown. This is not a revenge novel or movie, though the women, married and single, realize they’re “dreamers—women without a voice. Mennonites without a homeland. Even the animals are safer in their homes than we are.” Polley’s own Canadian life, from a movie-set childhood full of terrors (her bio is titled Run Towards the Danger) to her recent cine-memoir Stories We Tell, are filled with uncertainty, loss and fear. Polley has assembled a formidable ensemble—Frances McDormand, Jessie Buckley, Rooney Mara, Claire Foy, Judith Ivey, Sheila McCarthy, Michelle McLeod, for openers. What she’s created is a town meeting of women in a hayloft, figuring how best to move forward. She’s described how her movie raises questions about everything from systems of power, culpability and trauma to faith and forgiveness. Polley says it left her “bewilderingly hopeful.” And so it does. Polley and company take a fork in the road that’s pointed toward salvation. Her poster shows women holding hands, and one of her editors thankfully suggested a song other than “California Dreamin” for the soundtrack.

MeToo, Title IX and the Latest in Cancel Culture

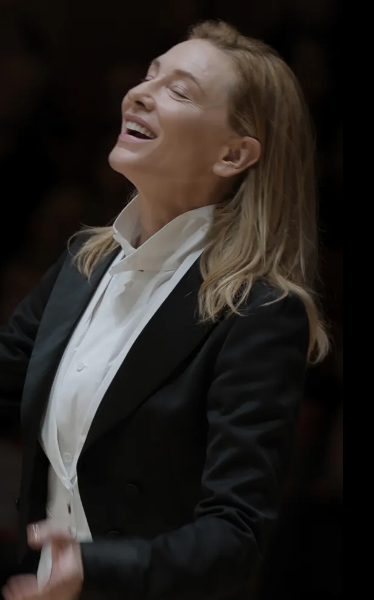

Tár. Playing Lydia Tár, the world-class conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, Cate Blanchett is in full throttle control of her fame and fortunes, her live-in German lover (Nina Hoss, superbly forlorn as her first violinist), their co-parented daughter, her Ph.D., her compositions, the album covers she controls, her “Tár on Tár” soon-to-be-a-bestseller, her late beloved mentor Leonard Bernstein, her knockout Q&A with The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik—all this opens Todd Field’s smashing, riches-to-not-quite-rags tale. As usual, the devil lurks in the details. Here it’s Tár’s lecture at the Juilliard School, on the same home campus as the New York Philharmonic where Tár was once the conducting maestro. Playing Bach’s “Well Tempered Clavier” on piano as she lectures in whole paragraphs to a bedazzled class, she’s abruptly challenged by one student who objects to studying anything composed by old white men. Their dialogue escalates in seconds into mutual hostility. The conductor reaches forward and lightly touches the student’s arm, more to make a point than anything else. Uh oh. All this is captured on devices by the awestruck class, as is the student’s stalking out, screaming curses at the teacher. The cell footage is cut into a scathing complaint that makes Tár look more like Vlad the Impaler, and will be a bad stumble on her way down. There are plenty of them in Todd Field’s icily abrasive dissection of the classical music arena. Tár doesn’t end up dead in disgrace like James Levine, or like Brad Cooper’s carny hustler in Nightmare Alley, begging for a job and a bottle. But the last audience we see watching Tár displaying her conducting skills is a stunning, head-scratching shocker. Brrrr.

Maria Schneider, 1983. The first and most lasting impression Schneider made on American moviegoers was in Bernardo Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris (1972), opposite Marlon Brando. The director talked Maria, who was 19 and playing Brando’s lover, into doing an unplanned and unrehearsed sex scene involving a butter lubricant. Though the anal rape was simulated, and involved only one take, the actress felt, and would feel until her passing in 2011, violated as a woman and as an actress. In a seven minute interview in 1983, on French television, she doesn’t want to talk about the experience, but does. Her humiliation and anguish are palpable. Director Elisabeth Subrin shows you this scene and then adds others that are cinematic tricks of immense originality. First Manal Issa, a French-Lebanese actress, reenacts Schneider’s words on camera. Then Aïssa Maïga, a French-Senegalese actress, does the same thing. At first you rub your eyes and ears, thinking there’s a mistake in projection or in the soundtrack. Gradually it dawns on you that there’s no mistake—that the other actresses are recreating Schneider’s experience, not only matching most of her words, but replicating her gestures of hopelessness. The point is made: countless actresses have been betrayed by men they trusted. It’s impossible to watch Schneider playing opposite Jack Nicholson’s in Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger, three years later—in which she’s an architecture student called The Girl who’s more of an intelligent and compassionate listening post, a far better role—and not recall her scene with Brando that did no more than break another glass ceiling in cinema. Sublin’s device of doubling and then again doubling Maria’s experience isn’t really a trick. It’s a 24-minute revelation.

She Said. America’s free press and its brand of legacy journalism aren’t winning many popularity contests these days. It seems like ages since All the President’s Men (1976) lionized The Washington Post for its takedown of Richard Nixon, and Spotlight (2015) honored The Boston Globe’s probe into sexual abuse in the Catholic church. The New York Times should fare better with director Maria Schrader and screenwriter Rebecca Lenkiewicz’s sizzling, of-the-moment update on sexual abuse in Hollywood, based on the book She Said: Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Helped Ignite a Movement, by Times’ reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey. But you never know—the movie does a warmup expose summary of the former President’s “Access Hollywood” tape (co-written for the paper by Twohey) that will probably condemn the movie to oblivion among most red state filmgoers. When She Said settles into probing scores of industry women trapped by predators starting in the 1980s, it gathers steam fast. And when reporters Kantor (Zoe Kazan, full of J-school curiosity) and Twohey (Carey Mulligan, more seasoned and apt to drop F-bombs) get Harvey Weinstein squarely in their sights, She Said rolls out its big studio assets—savvy production design, slick lensing and editing, a pulse-pounding score. The actresses playing some of Weinstein’s 80 accusers—Rose McGowan, Ashley Judd, Samantha Morton, Rowena Chiu, Jennifer Ehle—are 100% believable when they go on the record, and comprise the movie’s heart and soul. The New York Times’ editorial management (Patricia Clarkson, Andre Broughan as exec editor Dean Baquet) are cross-cut as adjuncts to the mission, and neither have the top staff appeal shown in Spotlight and All the President’s Men. Still and all, She Said is a popcorn movie you lean in to. A lot of Times’ readers couldn’t wait for the 3,300-word article Kantor and Twohey broke five years ago. The press screening at the spacious Walter Reade theater had its own NYC novelty—half a dozen security personnel (suited up, without photo badges) stationed on either sides of the screen, half way back and at the back of the auditorium, all watching the audience like hawks to make sure none of us were recording or camcording the movie. This was the first fest movie with indoor security, and not the only one in this 60th celebration. Piracy worldwide, like sexual harassment, is not going away.

Killer Movies

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. For this writer, the most trusted NYFF director during the last century was François Truffaut. You couldn’t go wrong with movies like Small Change, The Wild Child, or Day for Night. Times are tougher now; the names to trust these days are documentarians, and Laura Poitras equals her Oscar-winning Citizenfour. She could have fashioned an entire feature length documentary on the history of Nan Goldin’s protests at the world’s great museums, decrying exhibits and wings contributed by the Sackler family. The Sacklers owned Perdue Pharma, makers of the prescription painkiller OxyContin. Golden became addicted to the painkiller in 2014 for three years, now universally recognized as a gateway to heroin and fentanyl. With her advocacy group PAIN (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), Golden has stretched herself out on sidewalks worldwide—from Manhattan’s Metropolitan Museum to the National Portrait Gallery in London to the Louvre in Paris. Her strategy is destigmatizing the disease while getting funds for treatment, harm reduction centers and and rehabs for opioid addicts. Her street die-ins are dramatic and colorful—essences of a great doc. Time named her one of the 200 most influential people of 2022. That’s the beauty part. Poitras has chosen to bookend the beauty with a bloodshed centerpiece—hundreds of Goldin’s photos she voice-overs, while her slide projector clicks away through the life she nearly lost. It’s a daring strategy, contrasting her life in recovery as an activist with the life she nearly threw away as an addict. Poitras told the press how she’d come into the project when it was halfway finished (replacing another director who was pregnant) and convinced Nan to reveal herself through her photo work, warts-and-all. They’re two portraits—a noble presence flashing back into a tawdry past rooted in Times Square’s Tin Pan Alley bar and the downtown Soho club and drug scene. Both are ways, as Goldin acknowledges, to walk through fear.

Exterior Night. Three years ago The Independent chose Martin Scorsese’s NYFF opening night selection, The Irishman, as the lead review, but analyzed it simultaneously with Marco Bellocchio’s The Traitor, a saga of the Sicilian Palermo mafia in the 1980s focused on a foot soldier who kills his way up, much like Robert De Niro’s convenient assassin. Both Scorsese and Bellocchio were at the top of their respective forms, and it’s a thrill seeing them both back with distinguished new work. The preeminent Italian director can’t let go of the slaying of the Christian Democrat party president, a moderate who was trying to forge a working relationship with violent Communist party radicals. All of his bodyguards were slain in a traveling motorcade in 1978, and Moro was kidnapped. Bellocchio first explored the basic story in a 2003 feature, Good Morning, Night, rarely shown in America. This time he goes deeper, suggesting his own government as well as Pope Paul VI never supported building any kind of coalition with the terrorist Red Brigade. Moro, played with quiet gravitas by Fabrizio Gifuni, emerges as a truly tragic figure caught in a trap of his own making. It’s not unlike Scorsese’s Irishman, who the movie shows killing labor leader Jimmy Hoffa. But Scorsese chose to avoid the more tantalizing issue on whether De Niro’s obedient top gun had a connection with the assassination of President John Kennedy. Bellochio seems fascinated with whether the Pope could have done more than write a plea letter to the kidnappers. Scene after scene through more than five hours hints that there may have been a traitor somewhere in Moro’s cabinet or even his exterior night, a supposed compatriot out there who let him dangle and die. Like nearly all of Belloccchio’s richly opulent work, the trappings are dark and lush, the acting machined to a fine edge. This is rare cinematic excellence.

A military drama 60 years in the making

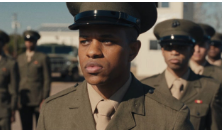

The Inspection. One can state with some certainty this is the first narrative drama about a gay Black marine. And with absolute certainty it’s the first narrative drama about a gay Black marine directed by another gay Black marine. And with jaw-dropping certainty it’s the first narrative drama about a gay Black marine made by a gay Black marine who dreamed his debut narrative feature would actually be shown at the New York Film Festival. That The Inspection was the Closing Night selection of the 60th NYFF tells you the next 60 years of world filmmaking are off to a far more promising start. The film grows out of writer/director Elegance Bratton’s own experiences growing up homeless and joining the military. Hollywood has a long history of showing raw recruits shaped into fighting machines, but this is the first to break important ground since the 1957 drama, The D.I., in which director Jack Webb cast himself as the rock-hard drill instructor in a movie almost entirely cast with real Marines. The Inspection posits a gay recruit, Ellis (Jeremy Pope) pretending to be straight—which his mother desperate hopes the marines will make him—and then is outed. Ellis’ sexuality becomes the looming question of whether he’ll even survive 13 weeks of boot camp, let alone the combat he’s being trained for. It’s an irresistible concept, and Bratton/Pope (both queer artists) deliver a message movie that should galvanize Black artistry into multiplex cinemas nationwide. A lot of the heavy lifting in Bratton’s vision is contributed by Gabrielle Union, who’s flawless in the thankless role of Ellis’ embittered mother, and Bokeem Woodbine, who strikes a razor’s-edge balance between ferocity and compassion, as his unit commander. “I will break you,” vows the instructor. But he doesn’t, and Woodbine is a far more believable breaker of recruits than Jack Webb.

The best short in the 60th NYFF

Same Old. Lloyd Lee Choi’s 15-minute tale of a young delivery man’s frustrating night, in Manhattan’s Chinatown, has also been shown at Cannes and Toronto. Choi is a Korean-Canadian writer/director who lives in Brooklyn, and makes his living shooting commercials for name brands. HBOMax is his guardian angel, and a feature film of this short is underway. It spotlights a significant population of New York City: service workers, often undocumented and barely noticed, who keep the big town moving. Nothing goes right for Lu the delivery guy (Limin Wang) on this particular night. Food orders are late arriving, tips are not forthcoming. A buddy tells him people without papers are being deported. His wife, who’s been laid off from her job at the nail salon, calls to report their goldfish has died and his mom won’t stop staring at it. Then his $1200 bike is stolen, and Lu’s rent is due that night. An old girlfriend offers him $33. A former employer turns away his plea for a loan. The pawn shop owner tells him his wedding ring is fake. Lu then commits an act of desperation, and at the last minute is able to pay his rent. On the way home, he buys a new goldfish. There’s a final scene when he arrives home, after his wife has asked how his day was and he mumbles “same old,” that’s played nearly silent. It’s Lu’s wife, serving her husband and his mother a simple late supper, that’s moving in a way that defies description. The director shoots nighttime in Chinatown with a cold, clear, unyielding feel that’s New York to the bone. For too many people, this city is heartless. But behind closed doors, countless tiny worlds with heartbeats exist. And sometimes, as with Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash, a short that was spotted at a film festival—no more than a fledgling director’s calling card—gets expanded into a feature that plays the New York Film Festival and goes on to win three Oscars. And that’s not just the same old.

The best feature in the 60th NYFF

Pacifiction. If you break down the title, it sounds like ‘a fiction of the Pacific,’ perhaps something like Joseph Conrad’s Outcast of the Island, or The Narrow Corner by Somerset Maugham. The title’s a fooler. Walk into this movie having done your homework on a hundred islands and atolls in French Polynesia that suffered the effects of undersea and above-ground nuclear testing periodically during the second half of the 20th century, concluding in 1996. Over 100,000 native people may have been contaminated, many weakened, scarred or lost to radiation effects. So when you see a uniformed captain and able-bodied sailors disembarking from a sleek craft for a night of leave at the neon-lit Paradise Night bar, right upfront, your first thought may be oh, director Albert Serra’s making a movie about what happened decades ago. But the premise of this intricate slow-burner—surely the slowest slow-burner in many a season, a picture that coils around you and then starts squeezing—is that what happened in a distant past was a prelude to what’s going to happen again.

Even though Serra tips you to his south seas pacifiction from the opening moments, shot entirely on location in and around Tahiti, he’s in no hurry to give away the movie’s secrets. (The director’s last memorable appearance at NYFF was in 2016, showing The Death of Louis XIV, which allowed Jean-Pierre Leaud the luxury of dying in bed for two hours, as well as giving the performance of his life.) When the High Commissioner in Polynesia, Monsieur de Roller, resplendent in double-breasted white linen suit folded closed over a silky tropical shirt, strides into the bar, instantly reading the room through blue-tinted glasses, he gives the initial impression of not knowing any of this. He’s played by Benoît Magimel in a staggeringly calculated yet outwardly slapdash performance that’s partly improvised. (Serra has admitted to whispering hints, suggestions, and ideas to his actor through an unseen earpiece. The technique is not unknown but it’s uncannily effective here.) The official is snooping. He’s trying to see behind what he and we observe. What’s this naval crew doing here? What are these reports of a submarine’s periscope being sighted off shore? Why are local native girls being rowed out at night for some far-flung rendezvous at sea or underwater? De Roller and Serra are going to spend the next two and a half hours putting it together for you.

The picture was reportedly shot with three Canon Blackmagic Pocket Cameras, lensed for widescreen ratio, and has a lush color palette that’s at once mood-altering. It flows like a vaguely noirish novel, in which each chapter has some kind of truly striking set piece. De Roller takes a meeting with distressed and threatened residents set to rally against renewed bomb testings. De Roller has a reunion with a pal who’s running for local office, way ahead of his opponents, and maybe this chap’s playing with a full deck and maybe he’s not. De Roller takes a survey flight over the ocean and island territory—accompanied now by Shannon (Pahoa Mahagafanau), a woman of impossible allure who may remind you that one of Serra’s admitted influences was Marlon Brando and his dalliances at what is now the ultra-luxurious atoll of Tetiaroa, just north of Tahiti. De Roller takes a jet-ski out into the ocean, dangerously near boats of natives barely bobbing over monster waves only a top surfer would attempt. Here’s de Roller cheering on a vicious cockfight choreographed to frenzied drumming and dancing…de Roller making his way through jungle to the shoreline and focusing binoculars on what appears a submarine periscope…de Roller encountering the drunken naval admiral at yet another bar…de Roller scrutinizing local girls ready to party, being rowed out to sea. De Roller is the fly on a wall that looks primed to crack open any minute.

Pacifiction joins a tiny and precious group of films to be studied forever as world cinema classics. Ofen they’re led and fed by madmen—Toshiro Mifune in Akira Kuosawa’s Throne of Blood; Albert Finney in John Huston’s Under the Volcano; Trevor Howard (and his tropical mistress Kerima) in Carol Reed’s Outcast of the Islands; Klaus Kinski in anything directed by Werner Herzog but especially Aguirre Wrath of God, and his documentary Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin, his gentlest adventurer; Janos Derzsi and Erika Bok as father and daughter in Bela Tar’s The Turin Horse. All are harsh, primitive, largely landscape immersions that make us face confounding universal truths. Like Pacifiction, they are cinema we can’t let go of, because they won’t let go of us.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in DOC/NYC, America’s largest documentary festival, Nov. 9-27.

Regions: New York