The New York Jewish Film Festival Jan. 14-28

An uptown museum and Lincoln Center fest offer unbending Jewish support in a time fraught with peril in the worldwide Jewish community

Attacks on Jews are a universal concern today. The New York Jewish Film Festival, co-sponsored by Film at Lincoln Center and The Jewish Museum, has thankfully returned in its annual 35th edition. Responding to political turmoil in all its local, national and global forms, NYJFF continues to embrace its eternal mission—illuminating, enlarging, interpreting and celebrating the Jewish experience in all its myriad facets.

NYJFF’s trim, tightly curated slate bristles with high energy, high impact films—eight narrative features, 13 documentary features, eight shorts. Some already have distributors (Menemsha, the premiere distributor of Jewish dramas and documentaries, has five.) Your critic viewed everything, upfront and over 14 days. Choosing a handful to recommend without reservation is a special pleasure this winter, for nearly half of this NYJFF’s feature films speak truth to power in some form. A number ‘poke the bear’ of evil regimes and men directly. A few might be described as the proverbial ‘canary in a coal mine,’ representing all too few voices. And what could be more important today than seeking out and helping lift those pictures into the global conversation? Producers, directors, writers, artisans in all aspects of production risk their futures—and sometimes their very lives—transmitting profound facts into feelings one experiences most fully on big theater screens. There’s cinema here that can help influence societal change. If reviewers don’t champion their excellence, who will? Here are four of-the-moment critic’s choices that demonstrate their timelessness.

Sapiro v. Ford: The Jew Who Sued Henry Ford: Gaylen Ross: U.S, Canada: 69 minutes

Before there was AI, there were deep fakes made by humans and not machines. The first your critic encountered in a New York movie festival, and was totally fooled by, was the 36 minute short John Bronco, conceived by Jake Szymanski and shown at the 2020 Tribeca Film Festival. It spun out a 100% invented yet 100% persuasive tale of an itinerant racing car driver (played by actor Walton Goggins), who presented as Ford Motor Company’s spokesman for its legendary SUV line from 1961 to 1996.

The spoof featured an archivist in Ford’s Dearborn, Michigan museum, displaying Bronco’s wardrobes, promos and ads over the years. Plus Ford Bronco TV commercials supposedly made by Ford’s New York ad agency, J. Walter Thompson. Plus celeb appearances by sports great Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, movie star Bo Derek and Trophy-Award Winner Doug Flutie, all fawning over Detroit’s #1 car maven. The odd thing was that in 1962, your critic was a copywriter on the Ford account at J. Walter Thompson, and had never heard of John Bronco. Ever. Szymanski’s clever plotting, persuasive writing and slick production conned even a young Mad Ave ‘mad man’ who should have been the first to recognize an avalanche of Ford-driven lies.

The goofy innocence of John Bronco sprang to mind viewing Gaylen Ross’s deadly serious documentary of the carmaker’s founder, Henry Ford, and his relationship with the early 20th century Dearborn Independent, whose masthead is shown above. (It has no relationship to your Independent film journal, founded in 1976, nor the online British newspaper The Independent, established in 1986, nor The Indypendent, a vigorous free newspaper since 2000, published in Brooklyn.)

Ford bought The Dearborn Independent in 1919 and moved its offices into his Detroit tractor assembly plant. The paper had been a monthly news digest with a lean toward the more eyecatching Police Gazette. Ford was a pacifist who laid the blame for World War I at the feet of Jewish financiers worldwide, especially in Germany. He also believed Jewish corruption and competition would cheapen and eventually destroy the emerging auto industry he’d pioneered. So his “Ford International Weekly,” published without advertising and sold on newsstands for a nickel, became Henry Ford’s personal in-house voice to the world. Little by little the car magnet encouraged his willing editor to pitch stories to reporters on Jewish influences, and especially Jewish immigration from Europe. The goal was convincing readers, story by story, that Jews were soiling not just American culture but American life itself, from dance to baseball to cigarettes. The paper’s circulation grew to half a million (close to The New York Times in the early to mid-20s) as Ford picked one agricultural organizer to direct his ire at, throughout 1924 and ‘25. Ford picked the wrong Jewish activist, who happened to be a lawyer.

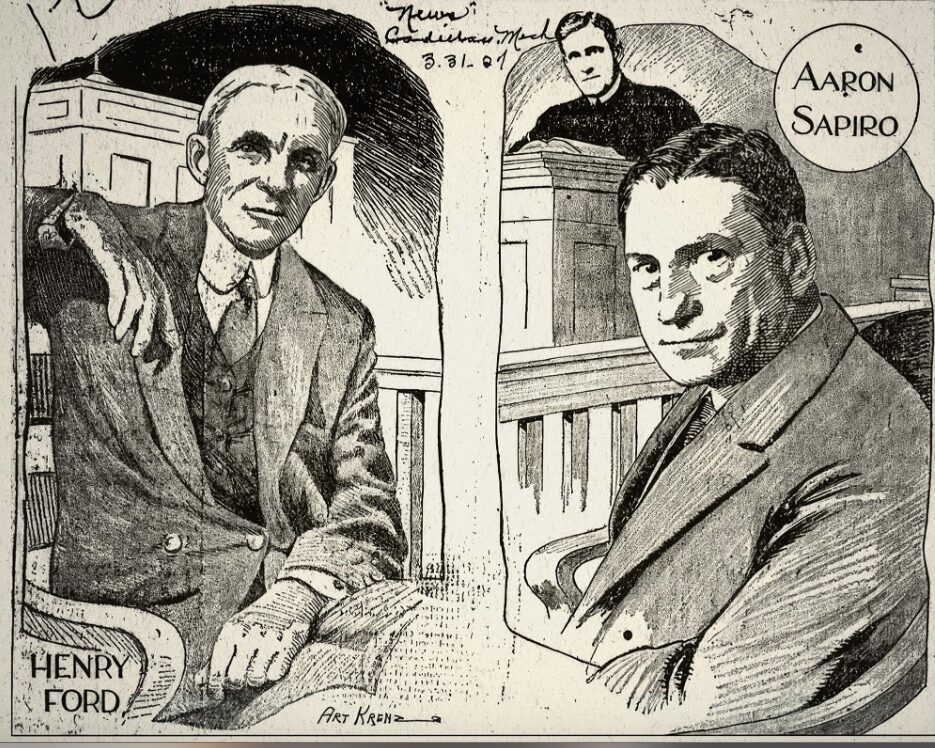

Aaron Sapiro was a dirt-poor California immigrant who worked his way through Cincinnati Law School, finding his calling organizing collectives of wheat, cotton and tobacco farmers throughout Canada. Sapiro’s work got under Ford’s skin enough that he launched 21 separate attack pieces on Sapiro, the farmer’s helper. The lawyer finally had enough and filed a libel suit in Detroit against Ford, seeking a cool million in damages. The world’s press was agog with shock.

Director Ross assembles the details with dispatch and authority. She brings in Jewish history professors from NYU, Brandeis, John Hopkins, St. Andrews, and U of Saskatchewan to buttress her narrative. Abraham Foxman, the revered former head of the Anti-Defamation League, weighs in. Sapiro wants to put Ford on the stand, but conveniently Ford is involved in a non-serious auto accident and the judge declares a mistrial. Ford, sensing a public relations disaster down the pike tells Sapiro he’s sorry, and quietly folds The Dearborn Independent. By this time Sapiro has lost nearly all his clients.

What are the lessons here? Co-screenwriters Ross and Carol King reference several in a chilling prologue of hate filled, Klan-inspired rallies led by today’s global hard right. Issues of The Ford International Weekly inspired Adolf Hitler, are quoted in Mein Kampf and fuel the reading of white mobs who march through American streets chanting “Jews will not replace us.” And what of Aaron Sapiro’s legacy? A piece of it at the time is ruefully heard in a Tin Pan Alley pop tune of the 1920s, written by showbiz giant Billy Rose and played on countless 78rpm turntables. Here’s a sampling of “Since Henry Ford Apologized To Me”:

I WAS SAD AND I WAS BLUE

BUT NOW I’M JUST AS GOOD AS YOU,

SINCE HENRY FORD APOLOGIZED TO ME…

I’VE THROWN AWAY, MY LITTLE CHEVOLET

AND BOUGHT MYSELF A FORD COU-PE

SINCE HENRY FORD APOLOGIZED TO ME

MAMA SAID SHE’D FEED HIM IF HE CALLS

GEFILTE FISH AND MATSO BALLS

I’M GLAD HE CHANGED HIS POINT OF VIEW

I EVEN LIKE THE EDSEL, TOO!

SINCE HENRY FORD APOLOGIZED TO ME

The First Lady: Udi Nir, Sagi Bornstein: Germany, Israel: 82 minutes

One sign-of-the-times is a neatly hand-lettered poster in the window of a beloved downtown Manhattan bookstore: “No Kings… Queens Welcome.” This snappy signal, quick as New York, tells you we’re still a sanctuary town, and that an autobiographical doc on Israel’s first openly transgender woman, Efrat Tilma, is going to be received with open arms. The First Lady earns its seat alongside previous critic’s choices Born To Be; Orlando, My Political Biography; and Tangerine, as cultural cinematic markers of the first order.

Based on her memoir, Tilma confidently narrates and voice-overs her life. She’s an authority at having survived all the dark Israeli alleys she was dragged into, much too early in life. Today she frets over her makeup, hair and wardrobe, demands and approves a classical music soundtrack that includes excerpts from Aida, Tosca, Norma, and Madame Butterfly. She says she only agreed to do a feature doc because directors Nir and Bornstein begged and badgered her for months. The First Lady has an arresting, at times baroque widescreen opulence, buoyed with pop-up animation flourishes that surprise and delight. It’s a showbiz tale shot through and through with depths of despair, against-all-odds humor, and ultimate triumph. Efrat Tilma starts as a nightclub wannabe songbird, migrating into a commercial airline stewardess for 22 years, then a uniformed member of the Israel Police Force for 11 years (including instructing officers how to properly respect LGBTQ+ persons). and finally at age 75 is achieving international recognition as a trans spokesperson. Quite some career.

The directors begin their reluctant subject’s tale with her teenage years as a crewcut boy, mostly raised by an abusive dad in Tel Aviv. She was a street kid, “a boy who just wanted to be a girl.” Befriended by the late entertainer Gila Goldstein, Tilma discovers the Sabra Club and its legendary headliner, Coccinelle, a movie star who’d had a vaginoplasty in Casablanca and eventually married three times, twice to men. Gila dresses her as a woman (Efrat wants a new dress for Purim) which shortly leads her to a first assignation with a maniac who nearly beats her to death. Instead of supporting her, Efrat’s parents kick her out.

Efrat tries Paris. She isn’t much of a dancer or singer, but she learns Audrey Hepburn’s secret from My Fair Lady of lipsyncing a pro singer. Next Efrat studies how Shirley Bassey moves. And so when Tilma belts out “I Am What I Am,” she really sounds and looks like an Israeli Ethel Merman, and brings down the house. This prompts Tilma to try the club scene in Brussels, where she’s promptly thrown in prison for imitating a woman. More misery. She moves to Berlin and in ‘71 heads to Casablanca for gender reassignment. And then starts those new careers as a flight attendant and an Israeli Police volunteer.

Directors Nir and Bornstein (Golda), who were Filmmakers-in-Residence at the Jewish Film Institute in 2024, shape The First Lady with scenes indicating their singular role in helping Tilma out of a profound depression following the suicide of her new partner, a Russian trans sex worker. Tilma had become a recluse in her Tel Aviv apartment, leaving the local police force after it turned against the gay community. Udi and Sagi logged four years on this doc and pulled her out at the 11th hour. Efrat Tilma is no longer lip-syncing someone else’s singing, but speaking out loud and clear in her own voice, all over the world as Israel’s First Lady. She appears to have found her true destiny. Sometimes it’s the canary whose voice carries the furthest in the coal mine.

Frontier: Judith Colell: 2025: Spain, Belgium: 101 minutes

Screen dramas of European Jews fleeing Nazi troops before and during World War II started with MGM’s The Mortal Storm in 1940. That remarkable Hollywood drama, from Phyllis Bottome’s 1938 novel, is set at a Jewish professor’s birthday celebration at his home in the German Alps—the same night in 1933 that Adolf Hitler becomes Chancellor of Germany. This emboldens a cadre of village brownshirts (Robert Young, Robert Stack, Ward Bond, Dan Dailey (all cast against their usual patriotic American personas and playing Nazis). When the professor and his colleagues are removed from their teaching positions, his frightened daughter (Margaret Sullivan) and her pacifist beau (James Stewart) barely escape, skiing down mountain slopes to Austria. The movie enraged Hitler, who banned all MGM movies during the war. Your recent similar critic’s choices from NYJFFs include Farewell, Mr. Haffmann, The Crossing, The Shadow of the Day, Past Life, and now Frontier.

Writer/director Colell sets her drama, much like The Mortal Storm, in a tiny forest hamlet, here in the Pyrenees mountains between France and Spain. It’s 1943, deep in the Nazi takeover of Europe. Even before the opening title comes up, the first scene—a Jewish refuge attempting night flight is shot dead in a forest—warns us what’s ahead. This is made clear the next morning to Manel (Miki Esparbé), the region’s Border Crossing Manager, whose job is to inspect the passports and German transit visas required for anyone leaving France for Spain. Manel and his wife Mercè (Maria Rodríquez Soto) live nearby with their three children. They’re intelligent, uneasy citizens who’ve been appointed by the dominant Nazi presence, and they’re horrified—but tightlipped—against the subjugation and now murder of their Jewish neighbors.

This is readily apparent when another band of refugee families arrives that morning asking for permission to cross, without the necessary credentials, and Manei dutifully turns them away. At the same time a Nazi convoy of trucks commanded by Lt. Sánchez (Asier Etxeandia) pulls in and begins arresting and hauling away families to internment camps. Manel scoots his watching wife and son back to their home, though the boy has already been alerted by his classmates that “the Germans are poisoning the Jews.”

Director Colell deftly posits the drama’s core questions: Will Manel (whose own secret past includes his desertion from the Franco forces in Spain) risk his own life and that of his family to save innocents? Will he figure out how to hide them locally while mapping out safe walking passages for them to cross the Pyrenees? Colell boosts the odds against Manel by inserting a village mayor who’s already in the pocket of the Nazi regime and launching his own night patrols, hoping to save his own life by sacrificing others who’ve enjoyed the right to live freely in France since the 16th century.

The character of Manel in Frontier introduces a pivotal figure in real life Jewish escape plans during 1943–45. Known as the posseur, this was an anti-fascist brave enough to risk all in the service of humanity. In France, the fictionalized Manel represents one of over 2,000 posseurs who helped over 80,000 Jews reach the dividing line between France and Spain, actually located high in the Pyrenees’s slopes and mountains. Some of these guides demanded suitcases of cash, others charged nothing.

The events co-screenwriters Gerard Giménez and Miguel Ibáñez Monroy weave into Frontier are complex and imaginative, involving the fiercely loyal bartender Juliana (Bruna Cusí), a rebel leader, a Jewish maid, even the son of Manel and Mercè who gets lost for a time in the towering Pyrenees forests. This is a taut, tense drama echoing much more than a footnote to history. Shooting in 35mm, which gives her authentic landscapes a rich, burnished luster, Colell builds Frontier with workmanlike precision. Etxeandia is suitably ominous as the Nazi commandant who’s confident he has Manel under his thumb, warning him that “thinking is an extravagance in wartime.” As husband and wife, Esparbé and Soto are strikingly believable, sorting through conflicting feelings in making the most risky decision of their married lives. Frontier is easily the top narrative drama of this NYJFF.

Neshoma: Sandra Beerends: 2024: Netherlands: 88 minutes

You don’t want to confuse Neshoma’s view of Amsterdam with Occupied City, Steve McQueen’s recent documentary of how Amsterdam survived World War II under the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. McQueen’s Occupied City was shown at the 2023 New York Film Festival. He filmed a virtually locked-down metropolis during the most severe opening months of COVID. Voice-overed by a dryly neutral Melanie Hyams, McQueen’s cameras prowled Amsterdam’s closed-up homes, emptied streets, shuttered storefronts, and the city’s barely functioning institutions. COVID provided a solemn, post-Holocaust canvas for reflection.

Seen through a 262 minute, block-by-block recitation of history, Occupied City reported on what happened to a cross-section of Amsterdam residents trapped or seized by the Nazi war machine. Most perished in concentration camps. McQueen’s doc used the stark visuals of a medical pandemic to hint at how the worst wartime catastrophe in history might afffect one city if it happened again.. One of its co-producers was Floor Onrust, who also produced Neshoma.

Writer/director Sandra Beerends’s Neshoma (or ‘soul’) is something else altogether. First and foremost it’s a thorough and revealing pre-Holocaust documentary of Amsterdam, and how the city changed, year by year, from the end of World War I in 1918 to its gradual involvement in World War II in 1942. Second, it does all this in a brisk and well paced 82 minutes. But Beerends’s real innovation is that Neshoma is a hybrid documentary.

It’s two decades of real-life history, embedded with a tiny, wistful story told throughout, voice-over, by a young Jewish girl, Rusha, in Amsterdam. She’s writing letters to her absent older brother, Max, in the Dutch East Indies. It’s what your critic calls a cine memoir, the most uncommon offshoot of the conventional docudrama. You’ve rarely if ever seen anything like it in NYJFF, and it’s a wondrous, truly enchanting experience.

Over a five year immersion (aided by six editorial researchers), Beerends braided together silent views of the city’s Jewish enclaves, representing 10% of Amsterdam’s population through two decades. We see the Jewish section painfully emerging from one World War, surviving the great Depression of ‘29 ,and eventually sliding under the weight of World War II. With her editor Reben van der Hammen, director Beerends chose snippets integrating the sights and sounds of narrator Rusha (the endearingly girlish speaking voice of Daniella Kertesz) in a loving family. Beerends bends her narrative to complement all the testimonies she researched over five years, as well as the images she and her editor selected. The narrative moves along like quicksilver because it’s one child’s voice becoming a grownup, opening the door to so many similar lives.

We watch a teen girl who might as well be Rusha play chess with the unseen Max. She discovers a boy she likes, ‘Fatty,’ and eventually marries. He’s a used book vendor in a marketplace stall. Rusha takes a job as a seamstress, sells tickets to fund a Jewish home for the elderly, eventually becomes a nurse and then a social worker. The couple go to the zoo, to the cinema, they ice skate and watch the Queen’s visits. They make a cozy home in an attic walkup. Children are born, holidays are observed. When the world’s markets collapse in ‘29, Rusha’s papa loses his income as a diamond cutter but finds work in the docks. In ‘33, the first refugees begin to arrive. By ‘40, Rusha no longer sees herself “as an Amsterdammer,” but a Jew out of touch with National Socialism. In ‘42, fearful of growing numbers of Nazi invaders, she and Fatty pack up their children and leave Amsterdam.

There are two other busy, behind-the-scenes wizards at work here, informing Beerends’s artful narrative: sound designer Mark Glynne, along with five sound editors, ‘manufacture’ realistic sound effects (from marchers’ boots to water lapping to doors closing) just as live radio broadcasts once did. They add vital touches of illusory reality to Rusha’s voice, in countless little ways that count up. The other soaring influence is Alex Simu’s music score—a never-ending tapestry of moods that brush and comb the imagery. Simu plays lead clarinet through it all, mournfully, pensively, joyously, magnificently. And if you’re curious whether Rusha’s brother Max receives (or answers) her 20+ years of letters, listen to the epilogue set in a much later year. Talk about soul. Neshoma is without question the most charming war documentary in many a NYJFF.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 31st annual edition of Rendez-Vous With French Cinema, sponsored by Film at Lincoln Center and UniFrance, March 5-15.

Regions: New York City