New Directors/New Films April 20–May 1

As New Yorkers struggle with BA.2 outbreaks, a film festival stays in person with a stellar lineup of international surprises

A major international hotel chain some years ago positioned its appeal to travelers as “the best surprise is no surprise.” The premise was that most vacationers want the predictability of home wherever they go. That line didn’t play well in Manhattan, where surprise is the order of every day. Most of us moved here to live from somewhere else, and part of the city’s endless attractiveness is its restless ability to surprise, as it tirelessly reinvents itself season after season.

New Directors/New Films, sponsored by Film at Lincoln Center and The Museum of Modern Art, has been unwrapping surprises every spring for 51 years. Their April gift to an uneasy populace that’s warily masking up yet again is the work of 39 directors, 21 of whom are women, from China, India, Norway, Argentina, Mexico, South Korea, France and Rwanda. This fest, like most ND/NFs, partly selects from award-winners at Venice, Cannes, Rotterdam and other world class festivals. You can’t get much tighter curating, anywhere you look.

In just the last decade or so, The Independent has played its part in heralding any number of rising newcomers with utterly original works:

Happy Hour, a five-hour meditation on the lives of four young career women by the Oscar-winning director of Drive My Car, Ryusuke Hamaguchi; Stories We Tell, Sarah Polley’s moving autobiography that sometimes slips into a fictionalized cinememoir; Nadiv Lapid’s The Kindergarten Teacher, an edgy Israeli meditation on a teacher’s obsession with a wunderkind poet; and Mia Hansen-Love’s tale of a French film distributor who’s too much in love with the moves, Father Of My Children.

Hopefully we’ll alert you to some of the next generation of shining stars, seen in these three feature choices plus two shorts choices. Each feature memorably mirrors the perilous days and nights of our lives, and all are end-destination films—big, outdoor pictures worth leaving your home to seek out on the biggest, widest, honest-to-goodness motion picture screen you can find.

Onoda – 10,000 Nights in the Jungle: Arthur Harari: France/Japan: 2021: 165 minutes

Russia and its invasion of Ukraine dominates the news headlines of the day, so it’s entirely fitting that the 51st season of New Directors/New Films leads with a biographical drama of one soldier, unique in its concept and breathtaking in its execution. French actor/director Arthur Harari has created an epic immersion in the life of Hiroo Onoda (1922–2014), the last soldier in the Japanese army to surrender almost 30 years after World War II ended. Make no mistake, this is a landmark cinema event that instantly stands with Kubrick’s Paths of Glory, Lee’s Da Five Bloods, Eastwood’s Flags of Our Fathers, and a little remembered but essential drama that played in Manhattan’s Japan Society exactly a half century ago, Under the Flag of the Rising Sun.

Onoda was no ordinary recruit. He’d envisioned becoming a kamikazi suicide pilot who’d be given enough fuel to reach and strike American ships, though not enough to return to base. But he had a fear of heights. So the military enrolled him instead in the Nakata School in Futamata, a secret operation under a tenacious major that trained up officers in the arts of resistance, adaptation and hand-to-hand guerrilla warfare. The major’s credo, embedded in Onoda’s brain and soul, was never to consider taking his own life and never, ever to surrender. “Mosquitoes who hang down from the ceiling are the ones who survive,” is his canny advice.

In 1944 Onodo was posted to an island in the Philippines with orders to destroy the airfield and harbor. Instead the island was quickly captured by U.S. forces, leaving the lieutenant literally in the dark with a handful of frightened recruits and several indigenous tribes of hostile fishermen. Onoda was told “we’ll come back for you,” and so, being a soldier trained to his core in obedience and duty, he waited three entire decades, “10,000 nights in the jungle.” As you may gather, this is not a movie about the horrors of any one war; what Harari has crafted may be the ultimate testament to the futility of all wars.

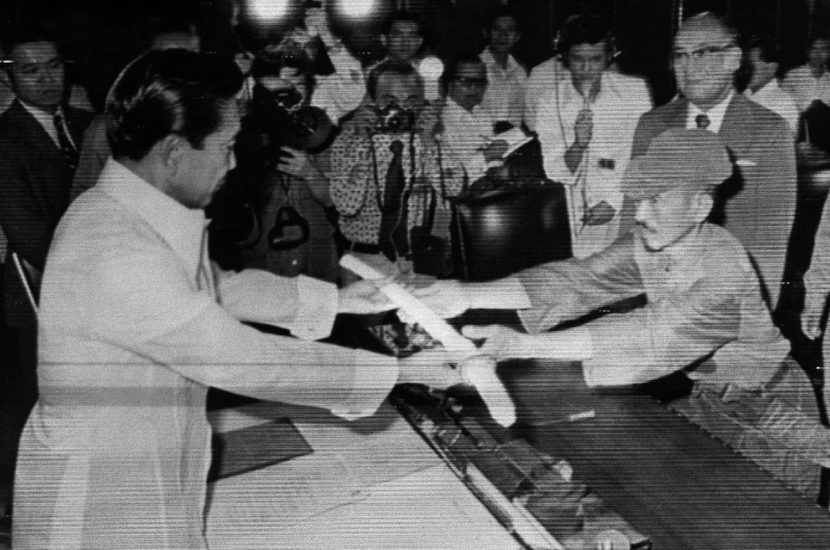

Director Harari rarely strays from how Onoda and his second-in-command, Kosuka, managed to ward off typhus, hunger, attacks by the ferocious natives, even visits by government officials and Onoda’s brother imploring survivors to return home following Japan’s surrender. Onoda rejects all gestures as enemy propaganda, especially live pickups of the moon walk on a Sony transistor radio left behind. The men repeatedly sing a patriotic anthem that promises the troops advance through the desert of sand, even if our caps freeze, on the front line for the Fatherland. The stalwart pair never lose faith that “our forces will gain control of the skies.” When Kosuka dies from poisoned arrows, Onoda camouflages himself head to toe in undergrowth so that he becomes indistinguishable from his natural habitat. It will take a visit from his original training officer, now an urban bookseller, to convince him to surrender his sword to the Philippines president, and accept a grateful nation’s thanks. Onoda lived to 91 and wrote a memoir, titled No Surrender.

This remarkable figure in history is played in the drama’s first half by Yuya Endo and then by Kanji Tsuda. Kosuka is acted by Yuya Matsuura and later by Tetsuya Chiba. The transitions are seamless, and all four actors are exemplary, as is Issei Ogata as the defining major who begins and concludes Onodo’s journey. Tom Harari’s cinematography and Laurent Senechal’s editing are Academy quality. The continuity of this nearly three hour movie is exceptionally clear and straightforward, probably because it hews so closely to how a military career became an unending struggle that need never have happened. Futility is not a common cinematic theme, but here it produces an unforgettable portrait of war for the ages.

Fire of Love: Sara Dosa: USA/Canada: 2022: 93 minutes

Miranda July, who’s the narrator of this truly terrifying documentary acquired by National Geographic, begins her voice-over with the news we’ve dreaded: “This is Katia. This is Maurice. It’s June 2, 1991. Tomorrow will be their last day.” The Kraffts were the world’s foremost volcanologist couple. both natives of northern France. And we know from the get-go they’ll be among the 43 who perish in a pyroclastic surge of fire and rock when Japan’s Mt. Utzen, dormant for 200 years, finally blows its top. Only bits of his camera and possibly her watch will be identifiable.

If it’s been a long time since you’ve watched a shock-and-awe movie in a real movie theater, the sensations of Fire of Love may equal your first moments staring up at IMAX or, even decades before IMAX, the dizzying effects of your first encounters with Cinerama.

Director Sara Dosa assembles and positions the Krafft’s lives as an eternal love story, though their risky and dangerous encounters tend to conflict with Dosa’s best efforts (co-written with producer Shane Boris and editors Erin Casper and Jocelyne Chaput). The director is a restless adventurer whose subjects have included mushroom hunters in Oregon woods (The Last Season) and an Icelandic grandmother’s life with elves (The Seer and the Unseen).

Her subjects here are not unlike modern day tornado chasers in America’s volatile heartland, except this geologist and geochemist paint themselves as “traveling performers” who are never happier than when Maurice is dancing along the precipice of one of 150+ volcanoes he filmed in 16mm and she photographed over two decades. One of Maurice’s unfulfilled desires, he confides, is having a helicopter lower him in a specially insulated canoe into a stream of flowing molten lava running down a live volcano. (He settles for a boat ride in a sulfuric acid lake.) “A volcano will kill me eventually, but that doesn’t bother me at all,” he says with wry fatalism. This is a doting husband who fries their eggs in a skillet he instantly heats on red hot magma. They’re the only talking heads you pay attention to for 93 minutes, and Maurice never stops chattering. No wonder Katie admits that whenever her husband disappears behind some volcanic mass, she frets she may never see him again.

When it’s not lauding this couple’s obvious devotion to each other, Fire of Love will teach you a few things about the perils of being anywhere near a potentially active volcano. Red-lava volcanoes are less likely to kill you because they follow predictable downhill paths; the Kraffts call them “friendlier.” But grey cloud volcanoes, packed with lethal gases and bursting “bombs” that can weigh tons and crush anything in their paths, are killers. Dosa’s assembly matches the Kraffts’ explorations: The first years of their red-lava journeys, which they survive with only a mud burn on Maurice’s leg, prompt them to concentrate the second half of their journeys on the smoky gray killer volcanoes. The mood steadily darkens, and then darkens more.

It’s here where Fire of Love veers toward a haunting resemblance to Werner Herzog’s 2005 Grizzly Man, which documented nearly five years of a naturalist’s pursuit and filming of a mammoth Alaskan bear. The creature, often shown in screen-filling closeups staring at his stalker without expression and without blinking, eventually attacked and devoured both the naturalist and his girlfriend. Only the man’s watch was ever found. Both he and Maurice Krafft share what the bombastic filmmaker describes as that “kamikazi” suicidal impulse, and Maurice is the first to admit he’s “playing Russian roulette” with his wife’s life and his own.

The difference is that once the Kraffts became the leading red-lava volcanologists, they devoted the rest of their careers to showing the world how essential it is to evacuate any living area vulnerable to a gray volcano eruption. They deliberately chose not to have children. Their photographic books, films, speaking tours, rock samples and knowledge—a peerless archive for National Geographic buffs—have unquestionably saved the lives of families wherever volcanoes are present, worldwide. No documentarian is likely to capture a “portrait of hell” more vividly than the Kraffts achieve in showing nature’s most awful awakenings.

Robe of Gems: Natalia Lopez Gallardo: Mexico/Argentina: 2022: 118 minutes

Seven years ago ND/NF showcased a documentary and critic’s choice on the Mexican drug trade, titled Western. Directors Turner and Bill Ross focused on Eagle Pass, Texas, on the border between the Rio Grande river and its Mexican neighbor, Piedras Negras, Coahulla. Their footage, now a decade old, canvassed an ever-smiling population determined to hide behind Mariachi bands, matadors, cowboys, fireworks—a community that appeared normal while concealing monstrous secrets. The crawl holes under the prison fences were visible, as were the bleached bones of residents who’d wandered into the painted desert and vanished. In Western, one sensed everyone on camera was lying to the filmmakers, and that life inside Eagle Pass was never “just another day in paradise.”

Robe of Gems fictionalizes an intense, scary tale of what may have been going on behind Western’s fake facades, primarily in the lives of three women connected to the omnipresent drug cartels. We observe they’re in very different social and economic environs. Isabel (Nailea Norvind), a well-to-do mother, is living a luxe life in the family’s; country villa. Her maid Maria (Antonia Olivares) may be webbed into the local drug dealings. Roberta (Aida Roa) is the stern mom and local police chief who appears to be the one honest cop in the territory, though false appearances don’t last forever in this movie. All three women are achingly believable, and (hard to believe) Ms. Norvind is the one professional actress onboard. The entire cast was recruited from Amatland, Yawtepec, Tepoztian and other Mexican locations. Not a false note in the lot.

Life on this hardscrabble land, which intermingles with deep forests and the occasional lush chateau, is messy and unpredictable; there’s a quiet apprehension infusing every scene. Natalia Lopez Gallardo, an experienced editor who’s helming her first feature, seems to intuit exactly how to maneuver mood and imagery, She’s already a pro in assembling what you’ll grow to regard as the chaos of normalcy. This is more of a rarity than you’d expect in a major festival film, and to discover it in a dope movie is exactly like finding jewels sewn into the lining of a beggar’s robe.

Gallarado is in no hurry to immerse you in these women’s lives. A whole extended family spends a long opening sequence, in the dark, digging around in a restricted zone for a missing relative. A police car near a checkpoint, passing by, urges them to move on. This is how Robe of Gems grudgingly begins a slow process of peeling away multiple layers of secrets.

A dad dreams of moving his family to America—everyone does. A boy is stripped of his earring and beads—“that narco shit”—by his grumbling mom. A husband fondles his wife under her blouse and then throws a hissy fit, breaking furniture, when she doesn’t respond—except she joins him and does her part, demolishing another chair, because she’s as frustrated by their trapped lives as he is. Outside one home, the children bob around in a ridiculously long pool; inside another home, moldy walls seep water. The director, who cut this drama with two other credited editors, deliberately holds on scenes a beat or two longer than usual, giving you time to think about and maybe connect all the dots she’s layering in.

One of the key truths Robe of Gems makes clear is that running guns in Mexico is as simple as visiting a gun show and stocking up, that smuggling a machine gun through checkpoints simply requires separating the working parts— the stock, the scope, the barrel—so by law it’s not a weapon. The boy absorbing this vital life information makes videos, but has barely learned to make a sandwich for his grandmother. Armed policewomen on duty tell admiring teens (who are high as kites on their ‘spirit gods’ mushrooms) “it’s easier to buy a 9mm Beretta near the border.”

Inevitably, betrayals occur. The director’s roaming camera and patient, considered editing don’t turn away from any of it. There’s no place to hide in this movie, unlike the way Eagle Pass hid in Western back in 2015. Film drama is distinctly different from film documentary, but once in a while it can be more truthful—and infinitely more tragic.

Two shorts long on artistry

Shorts have always been a filmmaker’s first and best calling card. In traditional and transitional societies, throughout the 20th century, the dream of winning a Hollywood Oscar for best short subject was beyond most filmmakers’ wildest dreams. That changed in 2002, when Tribeca’s Sharon Badal began seriously considering worldwide shorts. Other Manhattan festivals gradually copied the Tribeca model. Now all do. Tribeca logs in over 5,000 entries a year; around 60 are chosen, siloed by theme, and enjoy multiple, sold-out showings.

In 2010 The Independent became the first film journal to regularly critique the best festival shorts, giving them equal prominence with feature films. It was the first film journal and remains the only film journal to spot eventual Oscar winners like Shaun Christenson’s Curfew, Marshall Curry’s The Neighbor’s Window, Carol Dysinger’s Learning to Skateboard in a Warzone (If You’re a Girl), Frank Stifel’s Heaven Is a Traffic Jam on the 405, and, most recently, Ben Proudfoot’s The Queen of Basketball. Will either of the following ND/NF critic’s choices, each the simplest of human stories, join the Oscar parade? The first follows siblings reluctantly leaving primitive lowlands where their parents are buried. The second shows a young woman experiencing her first intimacy on a riverbank, so caught up in the passion of the moment with her lover that neither notice a fully grown crocodile, only a few feet away, its long snout at water level, sliding by without moving a muscle. Imagine.

Further and Further Away: Polen Ly: Cambodia: 2022: 24 minutes

A young woman, Neang (Bopha Oul) says a prayer to the photographs of deceased parents, in a modest rural home in northern Cambodia. Cut to her brother, Phai (Phanny Loen), putting the finishing touches on a seaworthy canoe he’s built, asking a fellow worker if he wants to go live in the bustling capital city of Phnom Phen. No, replies the chap, I’d rather stay home tending my rice. Cut to his sister, agreeing to come along on her brother’s motorbike, but only if they stop first to visit their parents’ resting place. In only a few more seconds than it’s taken you to read this, we’ve established where we are and the thrust of the story to be told. Clearly and concisely. This is one of the hardest disciplines for a beginning filmmaker to grasp. It’s another reason why only a tiny percentage of shorts submitted to heavyweight festivals like Berlinale, where Further and Further Away was last shown, make the cut.

Pausing on their journey, he shows her a phone image of the apartment he’d like them to rent in Phnom Phen. Speaking in the Bumong language, she says it’s too narrow. He notes friends waiting to greet them are hoping they’ll bring a chicken. Not a problem, as their parents raised chickens; we noticed Phai weighing one on an industrial scale and selling it to a neighbor earlier. Writer/director/cinematographer Ly is smoothly layering in the details of their lives. The boy seems ready to exit their dirt road village forever. Neang says she’ll go alone, if necessary, by herself to the grave. And she does, by canoe. The divide between a traditional and transitional generation is made cleanly, without fuss. This, too, is rare in international shorts.

We follow her as she attaches a simple offering to a tree in an area decimated to build a hydroelectric dam. This is the “old village” her parents were forced to leave. She weeps quietly as the director cuts to her brother, alone in the modern urban apartment he’s rented for them in the city. Neang climbs a tree to branches several hundred feet above the forest floor and nestles, unmoving.

The economy of this thoughtfully composed and executed short is as astute as its defining title. Ly has helmed eight short films and documentaries. in as many years. This one was supported by Angelina Jolie and won Ly a $5,000 Southeast Asian Short Film Grant at the Singapore International Film Festival. (Kindly note: It never hurts to have a recognizable patron in your corner.) Ly is more than ready to roll his first feature.

Crystallized Memory: Chonchanok Thanatteepwong: Thailand: 2021: 18 minutes

The things you learn watching 1,001 shorts. The birds’ nest pictured, adorned with crystalized jewels, is a staple in temples throughout Thailand. It symbolizes health, wealth and prosperity, as well as the transition of the body into a more bejeweled form following death. Imaginative chefs add a dollop of the saliva of switlets and whip up a birds’ nest soup, considered a delicacy in certain cultures.

The young couple (acted by Chanchanok Tharon and Pabutarn Boontarig) in this endearing coming-of-age short, start out admiring a hanging birds’ nest under the eaves of a small temple pavilion. Their mutual glances and body language signal they’re in love, They stroll about barefoot, discussing the disappearance of his father, which they believe to have been a supernatural phenomenon.

In a sylvan glade, they pause to share soups. A fly circles one of the bowls, and falls in. Later the woman fishes out not the fly but an insect no wider than a fingernail, just as he asks if she’ll bury or cremate him when he dies. Either way you won’t come back, she tells him. All these odd moments feel slightly awry as the nest bursts into flames. But you’re held by them.

Hand in hand, the couple stroll toward their romantic rendezvous in a moonlit night. The camera shifts to a tracking shot of that croc, nosing its way along practically under the writhing nude lovers coiled in their passion. It’s the closest thing to a magic realism sex scene in Thailand’s long history of repressive cinematic censorship. The bird’s nest burns away.

Early shorts that demand the viewer think through an oblique story, unresolved by the filmmaker, often don’t work. Crystallized Memory is a deep dive into interpretive Buddhist philosophy, worlds removed from the clarity of its Cambodian counterpart in and outside Phnom Penh. Yet both films capture the imagination in striking ways, introducing new directors staking their claim, requesting your attention and earning every second of it.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 21st edition Tribeca Film Festival, June 8-19.