New Directors/New Films April 3-14

As the Lincoln Center poster on Broadway says, “36 new filmmakers define the future of cinema.”

25 features. 10 shorts. Representing 30 countries. Already prize winners from Berlin, Cannes, Sundance and more. Curated by eight film aesthetes at the Museum Of Modern Art and Film at Lincoln Center. All for the 59th annual ND/NF.

The Opening Night selection, Aaron Schimberg’s A Different Man, has been described by a curator as “a delirious, complex and hilarious work that evokes the best black comedies produced on the streets and inside the apartments of New York City in the 1960s and 70s, with a healthy dash of body horror.” Distributed by the red-hot A24, it’s also co-produced by Killer Films and the veteran Christine Vachon, who produced the 1992 movie Office Killer, which could be described in much the same enticing language (“It’s murder working here,” read the poster for Cindy-Sherman-helmed thriller). 32 years later, Vachon’s still daring audiences to turn away from her images.

The Closing Night selection, Theda Hammel’s Stress Positions, is described by the same curator as “conjuring the messiness and irreverence of that era’s cinematic underground but in an utterly contemporary and accessible vernacular.” Distributed by the equally red hot Neon, this one is exec produced by acquisitions/production head Jeff Deutchman, son of veteran producer Ira Deutchman, whose Searching for Mr. Rugoff was a critic’s choice in the 2019 DOC NYC fest. Indie movie making does get passed down.

And so you might intuit that the future of cinema is partly standing on the unbending shoulders of women and men who once-upon-a-time built their own cinematic futures. Among your critic’s favorite ND/NF features and shorts first discovered and reviewed in The Independent, starting in 2010, were these newcomers, some of whom have actually become indie household names: Father of my Children (Mia Hansen-Løve); Bill Cunningham New York (Richard Press); LogoRama (François Alaux); Margin Call (J.C. Chandor); Black Power Mixtape 1967-75 (Goran Hugo Olsson); Incendies (Denis Villeneuve) The Raid (Gareth Huw Evans); Stories We Tell (Sarah Polley); The Babadook (Jennifer Kent); 20,000 Days On Earth (Iain Forsyth, Jane Pollard); The Kindergarden Teacher (Nadav Lapid); Quest (Jonathan Olshefski); Menashe (Joshua Z. Weinstein); Kaili Blues (Bi Gan); Happy Hour (Ryûsuke Hamaguchi); Good Manners (Marco Dutra, Johana Rojas); Clemency (Chinonye Chukwu); Honeyland (Tamara Kotevska, Ljubomir Stefanov); Two Of Us (Filippo Meneghetti); Onoda: 10,000 Days In The Jungle (Arthur Harari); Fire of Love (Sara Dosa); and Chile ‘76 (Manuela Martelli).

The past, as they also say, is prelude to the future, particularly the future of cinema. Here are this critic’s three favorite features in ND/NF 2024:

Malu: Pedro Freire: 2024: Brazil: 103 minutes

In the affectionate 2022 documentary Robert Downey, Jr., made about his filmmaker dad, aptly titled Sr., there’s a centerpiece scene that stops the show. Downey Sr. and Downey Jr., who’ve been yakking and chuckling through all the important and stupid movies they’ve made in two lifetimes, shift into a serious conversation about their mutual sobriety. The father offers a heartfelt and tearful apology—in recovery language, an ‘amends’—to his son for introducing him to marijuana at a very young age. Weed became, for the Oscar-winning (Oppenheimer) Robert Downey, Jr, his gateway into the incurable, lifelong disease that nearly killed both men. The scene is a spontaneous, unscripted father/son insight into cross-addiction and the unending process of their recoveries.

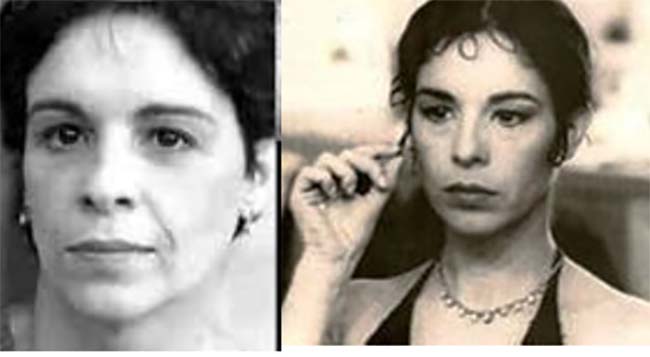

Pedro Freire’s feature debut, Malu, is a cine-memoir and tribute to his mother, the Brazilian stage actress Malu Rocha (1947-2013). It opens with Malu (acted in full-tilt firebrand mode by Yara de Novaes) lovingly rolling her first joint and high of the day, chilling out in the 90s Rio de Janeiro slum home she still co-owns with her long-exited ex-husband. Rocha was, as they say, a “holy terror” of the 60s and 70s who felt that priests were pedophiles who ate children, that all men were monsters, and that the only relevant theater was take-no-prisoners political drama.

It won’t surprise you that Malu sang “Aquarius” nude in a Brazilian touring company of Hair. She was an important member of Teatro Oficina de São Paulo; her closest American counterpart was surely Judith Malina, the fearless and formidable wife of Julian Beck and co-founder of Manhattan’s pioneering Living Theater troupe. Malu’s mother Lili (a poignantly long-suffering Juliana Carneiro da Cunha) apologies to the local priest for her daughter’s obscenity-laced rants, She also mutters what will become this movie’s overriding truth: “She’s a drug addict.” More precisely, she’s a cross-addicted pothead who drank freely and dropped acid—a locked-and-loaded, dyed-in-the-wool stoner.

Rocha is never without plans to erect a cultural center (complete with movie theater, library and retail shops) in the midst of Rio’s favelas with their leaky roofs and muddy streets. Her companion down the block, Tibira (an excellent Atica Bee), is a flamboyant gay actor who mom suspects may also be her drug dealer. The movie balances their off-kilter lives against the responsible restraints of Lili and a visiting daughter Joana (a perfectly cast Carol Duarte), an up-and-coming stage actress in São Paulo. Lili and Joana are constantly pushing against the hippie credo of the 60s, “keep me high and I’ll ball you forever,” expressed in far more explicit language by Malu. The director’s script and de Novaes’s cannonball performance nail the era with uncanny accuracy.

Freire also sends up warning signals that Malu can’t maintain these lifestyle tangents forever. We note in her confused appeal to a wealthy Black couple, potential investors, that she’s forgotten she made the same points in a prior pitch. Shortly after, Malu appears to suffer a seizure or mini-stroke. There’s a scene in which Lili wistfully wishes for a place to graze cows in their poverty-level neighborhood, a hint of a rare disease Malu may already be carrying. The actress keeps pulling it together until she can’t pull it together; she goes onto a cane and then into a wheelchair. Her freefall isn’t pretty to watch. Joana, the ever-faithful daughter, pleads for her mother to get professional help, but in the end she becomes Mulu’s last enabler: “I will take care of you until you light up your last joint.”

Pedro Fieire has fashioned the first theatrical cautionary tale against the worldwide legalization of marijuana. In Malu’s day and before, they were called ‘jazz sticks,’ becoming the gateway drug of countless jazz musicians globally, many of whom graduated to hard drugs and early deaths. The lessons don’t just come from Robert Downey, Jr. and Sr.

Omen: Baloji: Belgium: 2023: 95 minutes

Put your hands together and please welcome the most thrilling drama of this entire 2024 ND/NF festival. In the photo, the writer/director towers over his four leads, including (right to left): Marc Zinga, playing Koffi, the eldest family son and a more-than-passing link to the director’s early life and times; Eliane Umuhire, playing Tshala, Koffi’s younger sister; Beloji, who’s proven the staggeringly successful records he’s made were warmups for the serious feature film career he’s launching right now; Yves-Marina Gnahoua, playing Mujila, Koffi’s mother; and Lucie Debay, playing Alice, Koffi’s wife. All four actors are aces and flawlessly serve their director’s script

Here’s how Baloji’s real life echoes Koffi’s reel life: The director was born in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in ‘78. ‘Baloji’ originally meant ‘man of science’ in Swahili but over time has darkened to mean a conjurer of Black magic, a sorcerer. Baloji’s parents separated and he moved with his businessman dad to Belgian and then France, where street life, rap and hip-hop fused into Starflam, a band that garnered a platinum LP. Two solo albums and short films followed. This is Baloji’s leap into feature cinema, and he’s clearly landed on two feet, a prizewinner at Cannes’ Un Certain Regard and in Belgium as the country’s Oscar submission. Omen is a rich ethnographic portrait of a family’s stubborn resistance to change, mixed with jolts of shock-and-awe magical realism. The picture is a grimly escalating lesson that leaving a Congo home still steeped in tribal tradition and custom—fleeing to a European life and lifestyle—can bring withering resentment and banishment.

We first meet Koffi and his fiancee Alice in their Belgium home, as she dutifully trims away five years of Koffi’s locks. She’s four months pregnant (with twins) and they’re preparing to fly for his first visit in decades, remembering how his parents shrank from a ‘zabalo’ birthmark, considered a ‘mark of the devil.’ Koffi’s goals are to find support for his upcoming marriage, while presenting Mama Mujila with a modest dowry, saved from his job in a local school. Neither the Congo city nor country are named, though the bustling, crammed streets they inch their way through, toward a picnic ground, are still primarily served by outdoor markets and street vendors. What they’re greeted by at the family reunion are frozen stares and eyes that totally ignore Alice. Mama says nothing and Dad is working at his underground job in a coal mine. Sister Tshala is the one welcoming face.

Trying to establish a rapport, Koffi asks to hold a newborn of one of the aunties. At that moment—in a plot twist most movies couldn’t begin to get away with but Omen somehow pulls off—Koffi suffers a nosebleed and drops of blood fall onto the baby’s face. Chaos. The intruding native son is instantly branded a devil, tried, found guilty and abandoned in a field with his head locked into a witch mask. Alice has to knock it apart. Baloji has set the misery index at 10 and will kick it up much higher.

What makes Omen such a fascinating drama to behold is its insider view of modern-day Congo. From every perspective, it appears a society hopelessly mired in the inevitable collisions between rural and urban life. The most vivid recurring image is a mountain of coal—higher than the Christmas tree in Rockefeller Center—beneath which Koffi’s dad has worked all his life and where he will die. Next to the coal pile a boxing ring has been erected, in which rival gang members settle their differences, and in which we witness one kid simply draw a gun and shoot his opponent dead. In town, Mama Mujila and the local ladies do their socializing in an abandoned school bus, pictured, until they’re chased away by another marauding youth gang. A street parade with a coffin (with a live person’s and feet sticking out either end) has a shaman demonstrating the classic magic act of sawing a girl in two, to amazed spectators. There are burning straw men in the desert, and a covered native empties her breast milk into a stream, clouding it white. Mama Majila hysterically claws at the soil, hoping to find her lost husband’s remains. Koffi and Alice witness much of this with bewilderment. We watch it all and feel the same way. Black magic lives here.

Baloji divides his narrative into titled sections focusing on each family member’s travails, and what’s irrevocably clear is that no one who’s stayed in place has any kind of future. When Mujlla’s modest home is cleared for selling after her husband’s passing, the last remaining item Is a caged bird. It’s a brutal, desolate image. Baloji’s telling us, in T.S. Elliot’s words, that “the center cannot hold.” The omens in this spellbinding tale are everywhere.

Explanation for Everything: Gábor Reisz: 2023: Hungary, Slovakia: 152 minutes

If you’re up for a two-and-a-half hour immersion in how daily life in Budapest has been affected over the past 14 years with a hard-right prime minister, Gábor Reisz has this fest’s political powder keg ready for inspection. Here’s his carefully guarded POV as expressed in Cineeuropa last August: “I don’t even really know myself exactly where I stand, politically speaking: my parents were right wing, but my friends were the total opposite. I thought it was really important to show the characters’ positive and negative sides and to not opt for a traditional narrative with a protagonist and an antagonist. And I felt the same way when it came to society, because I wanted to show how each of the two political camps had their traumas and their grievances.”

From the evidence up on screen, life under Viktor Orbán for a middle-class architect/builder, György (a sterling, long-suffering István Znamenák) his wife Judit (Krisztina Urbanovits, fine) and their 18-year-old son Ábel (Adonyi-Walsh Gáspár, a sweetheart) is shrinking fast. Faucets leak, their refrigerator floods, prices are rising, mom’s buying day-old bread, clients come to dad with home plans they can’t remotely afford, György’s six-year assistant Is disgusted with the country and bails to Denmark. There’s drunk teens at night on the street under their tiny balcony, which views Budapest’s Liberty Bridge, which György’s dad helped erect. The father’s favorite actress remains Gina Lollobrigida, and his daily mantra is “As long as we get through tomorrow.” The director flags it more bluntly in an intertitle: “When Geörgy’s Tuesday Turns To Shit.” You get the picture.

The parents are banking Ábel will pass a stand-and-deliver oral presentation on a history subject, which will help admit him to a state-run university—and which the youth is not going to pass. We’ll learn from his ninth grade history teacher Jakab (András Rusznák, fierce and effective) that Abel cheated his way all through high school and is kind of an academic blank. Jakab, married with two daughters, is a dedicated if prickly academic who gives his classes a thorough grounding in the Holocaust, and shows them László Nemes’s Son of Saul in class. Jakab and György have tangled once in a parent/teacher meeting, and will later have a blistering confrontation scene.

When Ábel totally flubs his oral, frozen and unable to speak to a panel of teachers, we notice on his blazer (which he hasn’t worn in years) a Nationality Pin. This will become the movie’s singular object of interest, what Alfred Hitchcock called his ‘MacGuffin.’ Let the director explain its significance: “On the anniversary of the 1848 War of Independence, one of Hungary’s most prominent celebrations, it is customary to wear a nationality pin made up of the colors of the flag, and the perception of this has also become a political issue. The nationality pins displayed by the nationalistic side during party events and demonstrations changed the meaning of this symbol quite a bit in the past 20 years. While it once stood for Hungarian independence and a kinship to our country, today, anyone who wears it is deemed for the nation, and anyone who doesn’t is against it. This situation has gotten so bad that people don’t listen and understand each other.”

At this point in the movie’s narrative, you may become more aware of a mysterious young woman Reisz has been slyly teasing into scenes from the start. She’s busy on her computer or her phone, and the director has been previewing tiny pieces of the scenes she’ll now play out. Her name is Erika (Rebeka Hatházi, this ND/NF’s breakout star). She’s a wily, completely amoral reporter for Hungarian Days, an Orbán-friendly newspaper that Jakab describes as worse than Mad magazine and spotlights stories on the prime minister’s favorite movies.

Erika’s gotten a tip some high school kid may have flunked his exams because of a Nationalist Pin. She smells a story, and like the savvy journalist she is, Erika works her way back through a maze of leads—from a taxi driver who drove a doctor who treated György for chest pains, back through the wary school principal, to the confused Ábel himself. She sees there’s no smoking gun but proceeds to write the kind of story that exemplifies Joan Didion’s famous admonition, ‘writers are always selling someone out.’ Erika’s editor loves it, adding his own tabloid headline telling all of Budapest that a high school student flunked an exam for wearing that pin.

There’s much more for you to discover in this fascinating scandal. And you should. Explanation for Everything may sport the season’s most clumsy movie title, but the picture is a chilling and startlingly frank look into a Hungary most Budapest residents didn’t think could possibly happen. And they’ve been stuck living it for 14 years. It’s a cautionary tale in a 2024 that can’t have too many.

This concludes Critic’s Choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 23rd Tribeca Festival, June 5-16.

Regions: New York City